Exhibition Review: North Korean Perspectives

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

How Should We See Images from North Korea?

I have never been to North Korea, so writing a review about a photography exhibition about it presents a special challenge. As a contemporary art curator, I meet many international artists who have visited North Korea and, being from Seoul, I am also a Korean. Our two Koreas are neighbors and we share ancestors and history, but I know very little about the actual state of affairs in the north. I can only listen to artists’ stories about what they experienced in that closed society.

Last summer (in 2015), I curated an art project about the DMZ and spent six months preparing the exhibition at a site nearby. The village nearest to the border, Yugok-ri, is peaceful and boasts a superb ecological environment. Yet every morning, the villagers there are awakened by North Korean propaganda broadcasts. The distance is so short that you can’t miss the blaring announcements. In peacetime, life goes on normally, but nobody knows what will happen tomorrow. North Korea sits very close geographically, yet it is a most distant place in the hearts of South Koreans.

Throughout my childhood, in the 1970s, North Korea was depicted as a kind of imaginary country whose people were always on the wrong side of the scale measuring virtue and vice. In the elementary school social studies textbooks of that decade, North Koreans were depicted as wicked pigs, threatening wolves, or animals wearing human masks, or were presented as very poor, dirty, and suffering at the hands of their governing class of “animals.” At the same time, South Koreans were presented as upright and honest.

These textbook images of thieves, robbers, invaders, and other horrible, evil people made a strong impression on South Korean children. They stuck in young minds and continue to color our thinking about the north. My own negative feelings have certainly been strongly fixed, and are not easy to change even as an adult.

I remember when I first met North Koreans in person, somewhere in Europe when I was a college student. Initially I was frightened, and then I was surprised that they were as normal as other people.

I also recall the emotional moment when the two Korean teams entered under one flag at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, the first time such a thing had happened since the end of the Korean War.[1] As together they proudly entered the Olympic stadium, the world was astonished and the event engendered tears of rejoicing at Korea’s national unity. Politicians, governmental agents, the media, and all Koreans ardently cheered both the South Korean athletes and the North Korean athletes. All bad impressions about North Korea disappeared. They had become people like us, family rather than the enemy, heroes rather than evil creatures. During the competition, both sides, as well as the international media, encouraged and celebrated the reconciliation of the two Koreas. But that did not last long.

Nowadays no children in South Korea consider North Koreans to be animals; they are seen as the same as the South Koreans in books and daily TV programs. Young children, unlike the older generation, are no longer taught to hate North Korea. However, other ways of image making are being aggressively pursued with a view to criticize the north on social and political issues.

Images work like organisms, like living things that are manipulated by the dominant power in a society. The image of North Koreans changed from evil animals to normal human beings, but it seems to be gradually sliding back again. After obtaining the title “Great Successor,” in 2012, Kim Jong-un took power and aggressively continued the nuclear-weapons program that was pursued by his father, Kim Jong-Il, the “Dear Leader.” In the wake of his nuclear threats, North Korean images in the media changed rapidly. On the Internet, Kim Jong-un is often described as a pig or other animal. Currently, our world is dominated by the Internet and social media, where images are unexpectedly powerful. Now we are faced with the question of how we should see these images.

In the exhibition North Korean Perspectives, organized by the independent curator Marc Prüst and Natasha Egan, executive director of the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago,, photographers approached images of North Korea from their own perspectives. They used many techniques, formats, and materials: Instagram and Tumblr; 3D photographs; Photoshop and iPhones; appropriated propaganda paintings, postcards, and photographs; self-portraits; and Kodak Ektagraphic Audio Viewer Projectors, as well as videos and books.

According to Marc Prüst, this exhibition is divided into two main sections: one shows the government’s official version of North Korea and the other offers alternative views of the country. Prüst is interested in the production of the images and methods of image consumption.

All photographs in North Korea, including those from the media, tourists’ pictures, and art, are controlled by the state press agency KCNA (Korean Central News Agency), an organ of the North Korean government. Tours are also controlled by the state, and tourists’ photographs are censored to reflect official viewpoints. The North Korean government produces images for propaganda under the slogan “We are happy,” to celebrate the “Great Leader” and the “Great Successor” and to promote juche (self-reliance), the political philosophy that has been the official state ideology in North Korea since 1972.

Most photographs presented to the world are the official ones, but some unofficial images, with help from international journalists and photographers, have been leaked. All photographers who visit North Korea are allowed to shoot only in limited areas, and their cameras are reviewed and photographs censored. Even under this severe censorship, there are images that the state-appointed chaperons, or “minders,” have failed to spot. These feature a domain of photography beyond official control. They present in-between spaces that social systems and political surveillance cannot constrain. This is a domain that exists beyond good and evil, beyond harmony and conflict, beyond reality and imagination.

Photographers participating in North Korean Perspectives used their own diverse photographic strategies to reveal something between reality and the imaginary. They present the audience with the possibility of seeing into gaps that emerge through photographic representation, although this photography is not a “mirror of reality.”

Revealing the Ordinary

Pierre Bessard, a French photojournalist, was sufficiently trusted to meet the Great Leader Kim Il-sung several times, and he was able to take exclusive shots that are far different from the propaganda photographs created by the KCNA.

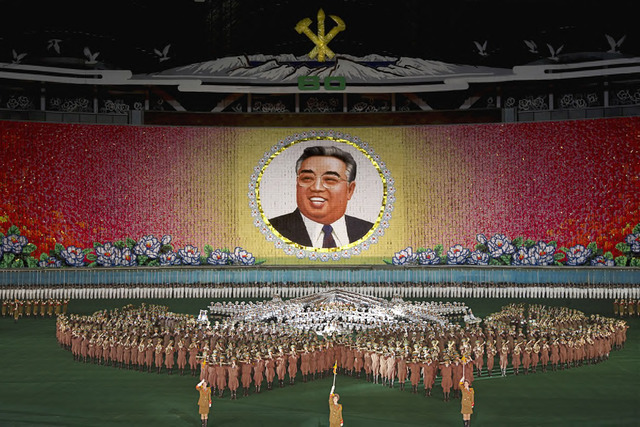

Fig. 1. Pierre Bessard, Opening ceremony of the anniversary celebrations of Kim Il-Sung at the Kim Il-Sung Stadium, Pyongyang, April 2000. Archival pigment print, 16 in. x 48 in.

Fig. 1. Pierre Bessard, Opening ceremony of the anniversary celebrations of Kim Il-Sung at the Kim Il-Sung Stadium, Pyongyang, April 2000. Archival pigment print, 16 in. x 48 in.Ari Hatsuzawa, a Japanese fashion and commercial photographer, makes ordinary lives of Pyongyang citizens seem to float on the surface of his pleasant, happy images in vivid color.

Tomas van Houtryve, a Belgian photojournalist, posed as a potential investor in North Korea’s chocolate industry and thereby gained some freedom of travel. He was able to shoot outside Pyongyang, where his distant photographs document ordinary people going about their everyday activities, along with images the North Korean government would not want to be seen by the outside world.

Fig. 3. Tomas van Houtryve, Korean woman loads a pistol for firing practice in Pyongyang, 2007. Archival pigment print, 16 x 24 in.

Fig. 3. Tomas van Houtryve, Korean woman loads a pistol for firing practice in Pyongyang, 2007. Archival pigment print, 16 x 24 in.Suntag Noh, a former photojournalist with a left-wing newspaper in South Korea, provides glimpses of social, political, and historical developments in the north. Noh describes the current state of affairs in Korea as “delayed danger” or “a state of uncertainty.”[2] The third image in his series, Red House III: North Korea in South Korea, reflects on how the north is shaped by the ideology of the south. With humor and a somewhat cynical eye, Noh finds similar scenes in the two Koreas and uses them to reveal that both societies are controlled by common impulses, even though they have different political identities. In the photograph “Hogisim (Curiosity),” a security agency in South Korea is taking a picture of Kim Jong-Il in the exhibition. After this, the Korean government closed the exhibition.

David Guttenfelder, the first staff photographer with the Associated Press office in North Korea, which opened in 2012, has taken photographs of ordinary, intimate North Korean scenes unrelated to journalism and uploaded them on Instagram. Communication between North Korea and the rest of the world has thus begun to be seen on social network services.

Fig. 5. David Guttenfelder, Examples of haircuts on display at a barbershop, 2013. Archival pigment print, 10 x 10 in.

Fig. 5. David Guttenfelder, Examples of haircuts on display at a barbershop, 2013. Archival pigment print, 10 x 10 in.A Cynical Attitude toward Propaganda

Alice Wielinga, a Dutch photographer, took pictures and then combined them with political propaganda paintings. Painting is the most common medium used in North Korean propaganda to deliver a message without a slogan. Wielinga links painting with photography in a way that highlights the gap between the real world and North Korean propaganda images.

Philippe Chancel, a French photographer, made images of sights around Pyongyang city. Celebratory photographs of monuments, statues, buildings, parades, and festivals are North Korea’s way of promoting itself to the observing world. Chancel’s work involves creating grand and beautiful photographic spectacles.

Fig. 7. Philippe Chancel, Arirang Festival to celebrate 90th birthday of the late Kim Il-Sung, 96 inches on the longest side.

Fig. 7. Philippe Chancel, Arirang Festival to celebrate 90th birthday of the late Kim Il-Sung, 96 inches on the longest side.Seung Woo Back, a South Korean artist, digitally manipulates North Korean propaganda images in his Utopia series (2008). He shows the futility of the government’s attempts to assert its utopian illusions; he further questions what, in most people’s minds, constitutes utopia. “Utopia” exists only as an elusive thing: an image that is beautiful on the surface but unattainable, something constructed by sociopolitical ideology and personal fantasy.

João Rocha, an art director at an advertising agency in Lisbon, started the project “Kim Jong-il Looking at Things” on his Tumblr website (http://kimjongillookingatthings.tumblr.com) and further developed the project with books and pictures. He presents the Great Leader’s propaganda images to the world from comical and cynical points of view.

Matjaž Tančič, a Slovenian photographer, and Hyounsang Yoo, a Korean photographer, are creating unique images using a 3D camera and a Kodak Ektagraphic Audio Viewer Projector. In particular, the artists have played with the methods of promotion employed by the North Korea press agency. Tančič made postcard-sized portraits of people using a 3D camera to exaggerate the images. Meanwhile, Yoo took the KCNA’s spectacular images from an Arirang Festival[3] and showed them on an out-of-date Kodak Ektagraphic Audio Viewer Projector. In these ways the artists sarcastically echo how North Korea insists on serving the leadership and their propaganda strategies by the use of old-fashioned techniques and media.

Fig. 10. Hyounsang Yoo, When Kim Il-Sung fought against the Japanese colonial power, he is said to have used two guns that were originally his father’s. Archival pigment print, 40 x 48 in.

Fig. 10. Hyounsang Yoo, When Kim Il-Sung fought against the Japanese colonial power, he is said to have used two guns that were originally his father’s. Archival pigment print, 40 x 48 in.Marie Voignier, a French filmmaker, shot state-run international guided tours but removed the guide’s voice, leaving only the ambient sound. International guided tours are very popular with foreigners, and the guides always retell the Kim family’s heroic tales and North Korea’s self-oriented history. Without the guide’s voice, the video enables the audience to see a less ideologically framed North Korean landscape and, in the absence of that framing, puts across the reality of that country’s forced communication.

As the exhibition North Korean Perspectives demonstrates, photographic images from North Korea are based mostly on propaganda, which means that in them, photography as representation is not operating normally. Photography generally proposes a spectrum of discontinuous choices and perceptions, but images from North Korea are to be shown for one purpose: to promote the country’s world in a very specific, “correct” way.

In this exhibition, however, the photographers try to open up ways of seeing and give us varied points of view about what North Korean images show. By taking on the role of observer, these photographers strategically appropriate propaganda images to portray irony and contradiction in a closed society. If we can see only controlled images, it is not important what we see in them; rather, we need to consider how we see them. The photographers here are seeking something beyond images of propaganda.

We must also ask some questions: Who is in charge of producing North Korean images? Of course, in the most obvious sense, the KCNA is in charge, but the outside world may be involved as well. Are we, perhaps, party to a photographic “conspiracy” to see images in one, manipulated way? The principle of producing images is not simple. Nor, then, should be how we interpret them. Maybe we want to see North Korean images out of curiosity about strange phenomena. But there is a story behind even staged images and propaganda, if only we know how to see it.

There are many issues and topics for discourse that emerge from North Korea, the “hermit kingdom,” where systems and thoughts are operating in ways different from those on the “outside.” The world might perceive North Korea as a country of monsters, as in the images from my childhood textbooks. The spectacle and the unfamiliar scenes might lead us to see a controlled surface and thus to misunderstand the reality. The problem is that attitudes and perceptions about North Korea are one-sided, without any questions or debates.

North Korea does not deserve to be considered only mysterious or so monsterlike. The nation in which the titles “Great Leader,” “Dear Leader,” and “Eternal Leader” are employed with great reverence and admiration, the nation in which pilgrimages to the birthplace of the Kim family in order to pay one’s respects are honorable, the nation in which outmoded forms of brainwashing still work—this is the country we seem to want to see. It is a world not available to our “common sense.”

Because the surface of images is vain and volatile and misunderstanding is all too easy, achieving the goal of a broader understanding of North Korea will take more creative efforts like the ones on offer at this exhibition.

Keum Hyun Han is an independent curator based in Seoul. She is chief researcher for the Photography in Asia initative of the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, and assistant professor of art at Sangji University, South Korea.

Notes:

After extensive negotiations regarding athletic exchanges between the South and the North beginning in the 1960s, a united Korean team was created for the 41st World Table Tennis Championships, in 1991. In the Sydney Olympic Games, a joint entrance was performed successfully but the South and the North competed separately.

Noh Suntag’s solo exhibition State of Emergency was shown at the Württembergischer Kunstverein, in Stuttgart, Germany, from March to May 2009 and at the La Virreinal Gallery, in Barcelona, in fall 2009. In this exhibition, Noh showed a total of one hundred ninety-six photographs from among his eight series.

According to the Russian News Agency (Tass), Arirang is a gymnastics and arts festival, a mass extravaganza that unfolds an epic story of how the Arirang nation of Korea put an end to the history of distress and rose as a dignified nation with the song “Arirang.” The Arirang performance is in the Guinness Book of World Records.