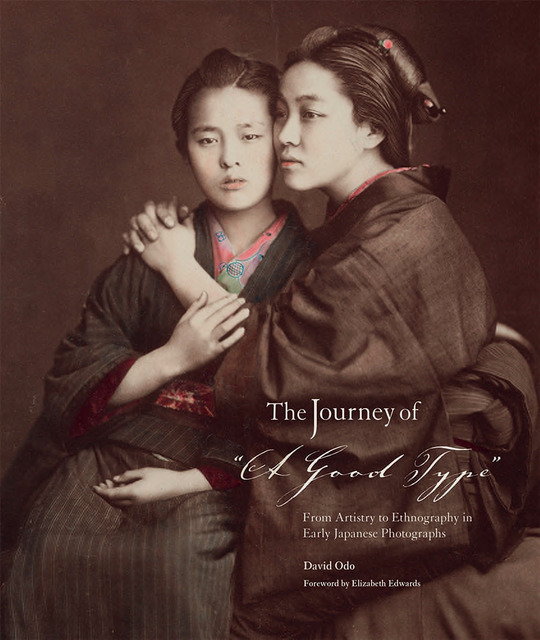

David Odo, The Journey of “A Good Type”: From Artistry to Ethnography in Early Japanese Photographs (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press, 2015, dist. Harvard University Press)

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Since its inception, in the 1980s, the study of early Japanese photography has steadily evolved away from concern with the immediate environments in which images were created to their varied afterlives in contexts geographically and temporally removed from their points of origin. With its focus on photographs in Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, David Odo’s The Journey of “A Good Type”: From Artistry to Ethnography in Early Japanese Photographs contributes to one outcome of this shift in the field: an emerging interest in institutional collections.

The role of photographs in the practices and discourses of colonial-era ethnography has been studied thoroughly, but Japan represents a unique and—until Odo’s intervention—understudied case. It was not colonized; thus, its people were not subjected to imperialist attempts to photographically document indigenous subjects or to the dehumanizing forms of ethnological photography practiced throughout the rest of the colonial world. For the most part, anthropologists interested in Japan relied on commercially produced photographs intended for tourists.

These unusual conditions frame the primary question underlying Odo’s study: How were souvenir photographs produced by commercial studios for sale to foreign tourists visiting Japan during the Meiji period (1868–1912) repurposed as objects of scientific study when they entered the archives of Harvard’s Peabody Museum years, and even decades, after they were created?

Odo adopts a two-part response to this query—a strategy that draws attention to the disparities between tourist photographs and the scientific purposes they ultimately served. Focusing on the production, marketing, collecting, and eventually the gifting of tourist photographs to the museum, the first two chapters explicate what was at the time a complex image economy that profited from artifice. Commercial photographers photographed hired models to perform stereotypes widely held by their foreign clientele. Hand coloring, regarded at the time as the hallmark of Japanese photography, provided additional opportunities to highlight and accentuate stereotypical features of the photographic image. The two chapters that follow position Japanese photographs in both the archival practices of the Peabody Museum and, more generally, in late-nineteenth-century anthropological and ethnological discourses.

With the first two chapters providing essential background information, chapter three emerges as the book’s linchpin. Several sections, covering a range of interrelated topics, lay the foundations of Odo’s arguments concerning the reapplication of Japanese tourist photographs to scientific study.

He begins by outlining the concept of “type,” a term widely used by nineteenth-century anthropologists to categorize peoples of the world. Physical traits such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and cranial shapes provided visual markers of racial difference. Cultural practices in the form of costumes, hairstyles, tools, weapons, ritual implements, and artifacts of daily life provided additional visual markers from which anthropologists could infer moral and intellectual development. Types were categorized hierarchically according to their relative distance from the apex of human development—inevitably, the adult Caucasian male.

Photographs played a critical role in late-nineteenth-century anthropology as an expedient means to record the visual determinants of a “type.” They were also integral components of larger efforts to salvage peoples and cultures that were rapidly disappearing through contact with Euro-American colonial powers.

To introduce the essential characteristics and functional applications of “photographic types,” Odo examines a selection of daguerreotypes depicting African slaves commissioned by the Harvard professor Louis Agassiz in the 1840s and fifties for use in his research and teaching on racial differences among African tribes. Using the labels Agassiz attached to the daguerreotypes and comparing the images of slaves to those of other peoples from the same commission, Odo sets up the argument he will later apply to Japanese tourist photographs by demonstrating how images produced by commercial studios become ethnographic types through their use as opposed to their production.

Turning to the museum’s institutional practices, Odo notes that photographs accessioned into the Peabody collections were usually mounted on paperboard to keep them from curling and to make them easy to file. The boards also provided venues for handwritten captions and curatorial classifications. Surveying several examples, Odo demonstrates how written information on the boards mediates the transition of a commercially produced image to its new status as an anthropological type. The phrase “A Good Type,” featured in the title of book, was one such caption, in this case written by William Sturgis Bigelow (1850–1936), whose collection of Japanese photographs came to the Peabody in 1927. Odo concludes this chapter by situating examples of Japanese photographic types in late-nineteenth-century ethnographic studies.

In chapter four, Odo utilizes Michael Herzfeld’s concept of “crypto-colonialism” to make the case that tourist photographs were a form of visual salvage. Though not colonized, Japan was nonetheless dependent on foreign trade and expertise in its drive to modernize. Moreover, Japan’s commitment to modernization had a deleterious impact on its traditional culture. Odo cites several prominent foreigners bemoaning the rapid disappearance of traditional Japan, observing as well that the rhetoric of tourism was predicated on a similar sentiment. By capturing aspects of traditional culture threatened by modernization, souvenir photographs aligned with the desires of tourists to memorialize traditional Japan.

Though it is unlikely that tourists acquired commercially produced photographs of Japanese types specifically as a form of visual salvage, these images nonetheless provided sufficient visual data for ethnographic research and teaching structured by this imperative.

The Journey of a “Good Type” addresses a troublesome gap in our understanding of an important post-purchase application of Japanese tourist photographs. We have habitually (that is, lazily) acknowledged that souvenir photographs served ethnographical purposes—David Odo’s thoughtful and succinctly written arguments have finally shown us how and why this was so.

Allen Hockley teaches a broad range of courses on Asian art history at Dartmouth College. His scholarship engages two fields: early Japanese photography and Japanese woodblock prints and illustrated books of the Tokugawa through early Shōwa periods.