Omar Imam: Humanitarian Surrealism

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Still from a video directed by Omar Imam and published under a pseudonym in 2015. The artist does not use his name so Syrian warlords cannot track him down.

Still from a video directed by Omar Imam and published under a pseudonym in 2015. The artist does not use his name so Syrian warlords cannot track him down.Omar Imam studied accounting and began making photographs and films in 2003, inventing his own brand of dark ironic personal work in his hometown of Damascus. He left the country in 2012.

Publicly, he gives only vague details of his life and uses a pseudonym to produce photographs and films about the war. There are two reasons for this. First, if his name were associated with his pseudonymous pictures or if he says something controversial, Syrian warlords could use Google to track him down (“Words are dangerous” he says. “Images are different, not so easy to track”). Second, he does not share the dramatic and sometimes horrifying details of his life because he disdains being known as a refugee/victim. Imam is aware of how refugees have been depicted over the past half century. He wants his work to be judged on its merits, not on what others might assume about his artistic intentions from his own dramatic narrative.

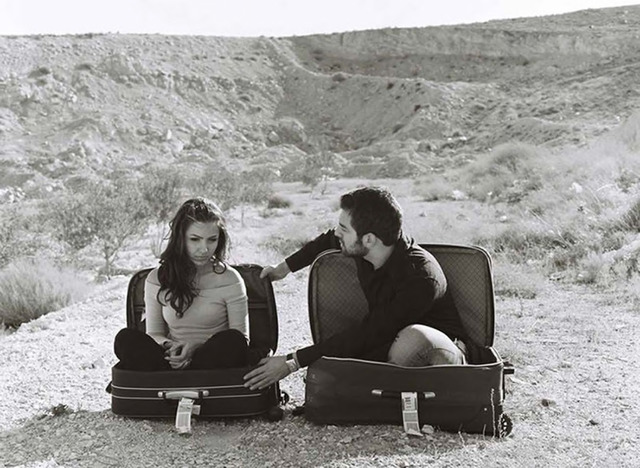

Omar Imam, Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “This photo was made in 2008, about 3 years before the volcano in Syria, even at that time youth felt they can't call Syria ‘home.’ The suitcase was an element for my composition and for my generation as well.”

Omar Imam, Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “This photo was made in 2008, about 3 years before the volcano in Syria, even at that time youth felt they can't call Syria ‘home.’ The suitcase was an element for my composition and for my generation as well.”After 1945, in the wake of World War II, broadcast television was invented and the global humanitarian-aid complex arose. These twin ventures—depicting and rebuilding—formed a symbiotic relationship. “Humanitarian action seems not simply to take advantage of the media,” writes the critic Thomas Keenan, “but indeed to depend on them, and on a fairly limited set of suppositions about the link between knowledge and action, between public information or opinion and response.” Out of this symbiotic relationship, cameras came to alleviate misery in the wake of war, and those who wielded them were expected to use them to solve problems for the displaced.

In Omar Imam’s work, there are no solutions. His pictures, different in composition as well as intention, directly question the conventions of “humanitarian photography.” He often sets his pictures in front of the ubiquitous white tents that appear in photographs distributed by the NGOs and UN agencies that run the camps in northern Lebanon in which he works. In his photographs, the tents do not represent shelter provided by the global community; rather, they are curtains in front of which is revealed the theater of life.

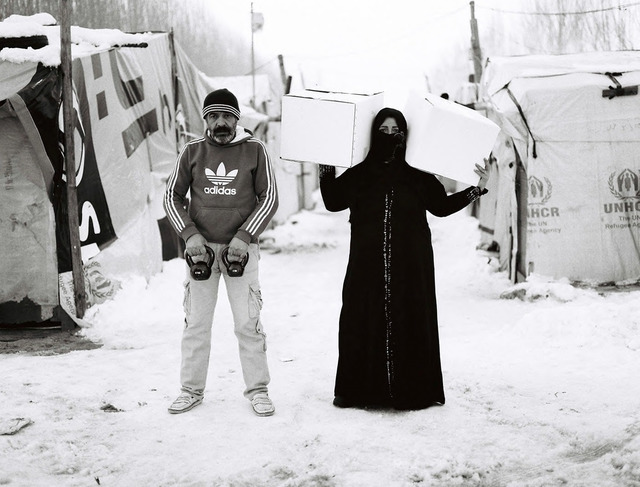

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “I was afraid when it was calm, when they checked to see who had passed away and who was injured. I felt safer in the midst of the shelling. I preferred to sing or listen to music when it was calm.”

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “I was afraid when it was calm, when they checked to see who had passed away and who was injured. I felt safer in the midst of the shelling. I preferred to sing or listen to music when it was calm.” Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. "There was only grass. I couldn't pass it through my throat, but I forced myself to swallow it in front of the children so they would accept it as food."

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. "There was only grass. I couldn't pass it through my throat, but I forced myself to swallow it in front of the children so they would accept it as food."A woman sits at a table and a waiter brings her food. At first glance, it seems to be a formal outdoor restaurant overlooking the water. There is a tablecloth, a wineglass, the waiter has good posture and wears a dark jacket. Upon deeper inspection, the initial impression falls apart. The water ends a few meters beyond the table, the scowls on the faces of both waiter and diner are severe, the dinner plate is broken, and what looked for a moment like an artisanal salad on the waiter’s tray is in fact a pile of weeds. “There was only grass,” the accompanying text reads. “I couldn’t pass it through my throat, but I was forced to swallow it in front of my children.” Imam confronts the viewer’s gaze with what at first appears mundane but on closer inspection also seems inconceivable. The images demand that the viewer look more deeply. Lurking in the distance, out of focus, are those white tents?

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “But at least before we divorced, he was useful in keeping harassers away from my daughters.”

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “But at least before we divorced, he was useful in keeping harassers away from my daughters.” Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “Now that we are in the camp, she brings home the food. Our testicles are in danger.”

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “Now that we are in the camp, she brings home the food. Our testicles are in danger.”Imam’s dreamlike photographs vacillate between mundane documents and utterly inconceivable scenarios. They cannot possibly have happened and yet here they are. Unlike “humanitarian photography”—which, moving as it is, reinforces the imagination of anonymous masses of suffering refugees—the impact in the grass picture comes not so much from knowing that the people in it are displaced (though they are) so much as from realizing that the viewer’s imagination can be reordered. Imam directs the viewer with precision. The images do not depict a situation so much as they seem to expand the space and time of the subjects’ reality, thus giving the viewer a way in.

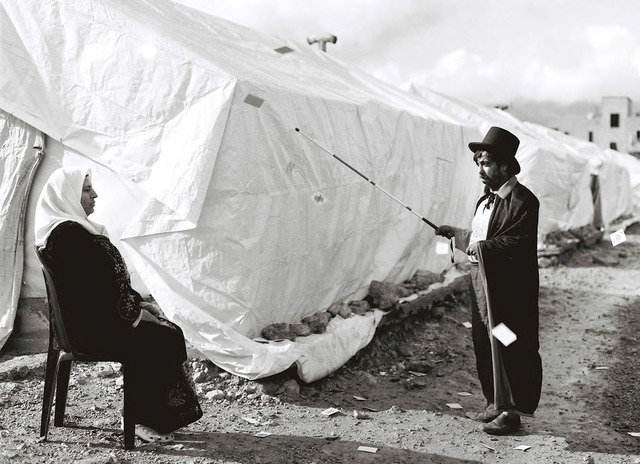

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. "In Lebanon, I found myself in narrow places. I start feeling anxious now when I am in an open space."

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. "In Lebanon, I found myself in narrow places. I start feeling anxious now when I am in an open space." Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. "My wife is blind... I tell her the stories of her favorite TV series and sometimes change the script to create a better atmosphere for her."

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. "My wife is blind... I tell her the stories of her favorite TV series and sometimes change the script to create a better atmosphere for her."In the nineteenth century, the photographer was a magician. Photographic technique was cloaked in mystery, so photographers passed off fictions, double-exposures, and manipulated images as evidence of ghosts. Here, a blind woman sits before a man in a black top hat and cape, waiting for something to happen. He stands in front of a tent and holds up a slightly too-long wand (her cane). Cards are moving through the air. Is she waiting to be healed? Is she blindly watching a show? The viewer does not know what to expect. Does she? Does he?

The magician, the one with knowledge and the ability to surprise, is not the photographer; he is her husband. The ones with transformative powers, the healers, are not the NGOs or aid workers; they are the refugees themselves, and they heal one another.

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “For a moment, I felt like we were talking to a car technician—not a doctor. We are refugees, but we are still human.”

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “For a moment, I felt like we were talking to a car technician—not a doctor. We are refugees, but we are still human.”In 2014, a photograph released by the United Nations from the Yarmouk camp, near Damascus, showed thousands of Palestinian refugees waiting for humanitarian aid. The picture was published by more than a thousand newspapers, viewed tens of millions of times on social media, broadcast on the enormous screens in New York City’s Times Square. Devastating, tragic, beautiful, the image depicts masses of people cascading down a street lined with the skeletons of former buildings.

A dispute arose over the veracity of the photograph. The New York Times wrote an article. An Ivy League professor analyzed the image with software intended to detect photographic fakery. “The photo is an exact replica of reality,” insisted a UN official. “I can understand why that reality would beggar belief. But in the 21st century, such a scene exists.” (The picture was, in fact, real.)

This question of veracity began with the advent of war photography, when Roger Fenton staged cannonballs on a dirt road during the Crimean War in order to exhibit horror. Imam constructs a parody of this idea in the image below. Omar Imam’s photographs and films alter the question from “Is it real?” to “What are you seeing?” Aware of the archive of past and present war photography already in our minds, he makes images that force viewers to critically engage with what we know (or don’t know) about the war in Syria.

Imam must contend not just with the fraught tradition of “humanitarian photography” and the viewer’s exasperation with unimaginable realities. He must also work in defiance of a more recent and dangerous strain of surreal imagery, videos produced by members of ISIS chronicling their violent acts. For Imam, ISIS is not only an unimaginably violent group of monsters; its members are also image makers. Somehow, between the self-righteously humane NGO photographs and the intentionally inhumane ISIS images, Imam is carving a path that dissociates humanity/inhumanity from understanding other human beings. Our connection to each other is not sentimental; it is experiential. We occupy this world together and must figure out how to order ourselves within it.

This becomes evident in the surreal juxtapositions that appear in Imam’s short films. A little girl, marched into the desert in an orange jumpsuit and a wedding veil, points a gun at the camera and shoots bubbles. A violinist wearing a gas mask in the back of a truck plays a solo, then a hand reaches into the frame to lift the mask and offer the violinist a cigarette. Are these acts violent? Are they humorous? Are they both?

“Surrealism,” writes Susan Sontag in On Photography, “lies at the heart of the photographic enterprise: in the very creation of a duplicate world . . . narrower but more dramatic than the one perceived by natural vision.” Decades of documentation of refugees from conflicts around the world have flattened the refugee into a trope: isolated from his nation, seeking shelter, in need of assistance, competing with masses of others for resources. Images of desperate and innocent civilians have become visual signifiers of conflict and yet increasingly communicate little about the systemic causes of war or the specific situations of individual human beings. Photographs of refugees are visual signifiers that say “Conflict has happened; I am the result.” The photograph is static evidence.

The subjects of Omar Imam’s photographs refuse these oversimplifications and insist on expressing themselves as complex individuals, even mythical characters—a blind man becomes a magician to cast a healing spell on his wife, a girl becomes a dragon to overcome the burning memories of sexual abuse. In these images of dreams, the photograph becomes an active space in which the subject has agency and transformation is possible. Paradise starts here.

The refugee in previous photographs is on the run, left alone without a nation; in Imam’s duplicate world, these civilians have reconstituted their compatriots in a foreign land and constructed anew a sense of belonging to replace the conflicted nationalism from which they must have fled. In one picture, his characters pose for a team picture in black-and-white-striped football uniforms. Sports teams offer fans (just as nations offer citizens) a sense of belonging. Imam’s team appears unlikely, cobbled together, individuals with individuality and yet deeply connected. Unity and disunity can coexist, unlike in the nation they left behind.

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “Through this project, I was able to rediscover my story through their stories. I'm a Syrian refugee myself, and we are making one team."

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. “Through this project, I was able to rediscover my story through their stories. I'm a Syrian refugee myself, and we are making one team."Imam places himself in the picture, arms around his teammates. He is the photographer but he equates himself with his subjects. The borders—between photographer and subject, between humor and tragedy, between subject and viewer, between citizen and refugee—blur and break down. In the slight distance between reality and the world of these images, viewers can imagine themselves there and, paradoxically, can more easily imagine the horrors of war.

“I do not teach history in my films,” said Elia Suleiman, the iconic Palestinian filmmaker. In the artist statement for Live, Love, Refugee (a verbal play on the Lebanese Board of Tourism’s slogan, “Live, Love, Lebanon,” and a project that Imam produced as a grantee in the inaugural round of the Arab Documentary Photography Program), Imam says something similar about his photographs and videos: “I want to disrupt the audience’s expectations of images of refugees and to present them with questions rather than answers.”

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. "The gap between me and my memories from Syria is growing bigger. I'm afraid of the blankness."

Omar Imam, Live, Love, Refugee series: Untitled, 2015 © Omar Imam. "The gap between me and my memories from Syria is growing bigger. I'm afraid of the blankness."Surrealism, what Sontag calls the “creation of a duplicate world,” offers Imam and his subjects the opportunity to take the remnants of identity they carried with them and forge them anew. The viewer, steeped in the humanitarian photographic narrative of refugees, encounters Imam’s images with surprise. Nationalism and charity may be more obvious forms of binding people together but they are perhaps neither the only nor the ideal ones. And so if the image of the outcast is no longer one that demands sympathy for his lack of a nation but instead equates the refugee with all viewers, what else can be reshaped or reordered?

Eric Gottesman is a 2015 Creative Capital Artist and a visiting professor at Hampshire College. His first monograph, Sudden Flowers, was published in 2014 by Fishbar Press.

Editor’s Note: For more information about the Arab Documentary Photography Program, see the profile and interview by TAP Review intern Isoke Samuel here.