Deepali Dewan and Deborah Hutton, Raja Deen Dayal: Artist Photographer in 19th-Century India (New Delhi: The Alkazi Collection of Photography; Ahmedabad: In Association with Mapin Publishing, 2013) 231 pp. ISBN 9788189995768

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

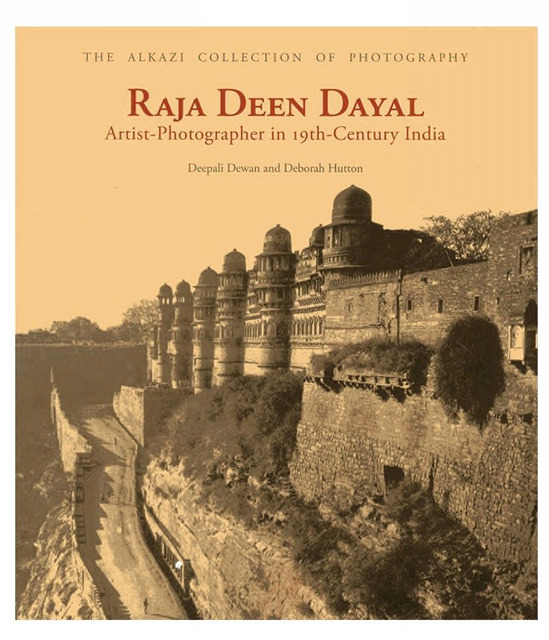

Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1904) has a mythic stature in the history of South Asian photography. He stands out among 19th century photographers for making stunningly beautiful images and establishing a commercial empire with which he served the interests of his many clients over a thirty-year long career. Dayal began as a photographer in 1874 at the British Public Works Department for the Central India Agency, located in Indore, Central India. During a two-year furlough in 1885-1887, he transformed himself from a government employee into a professional artist, traveling to North India and photographing British dignitaries at the summer capital of Shimla and documenting tourist sites, such as the Taj Mahal. In 1887, he went to Hyderabad and soon became the state photographer of H.H. the Nizam of Hyderabad, Mehboob Ali Khan, earning the title “Raja Bahadur Mussavir Jung (roughly, ‘a prince among artists’)”. In 1897, he also opened a studio in Bombay.

Dewan and Hutton take a close look at the development of an astounding career. In their book Dayal emerges as a quintessential photographer of the British Empire in India, leaving behind an extensive record particularly of the British system of indirect rule through which Indian princely states maintained sovereignty over their territories. The collaboration leads to a fine investigation. The authors take their research agenda to multiple archives in India, the USA, and Canada. They include unpublished materials, discovering Dayal’s personal photographs and records at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, and a collection of studio registers and glass plate negatives Dayal’s descendants gave to the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in New Delhi. Elegantly reproduced images in this volume come mostly from the Alkazi Collection of Photography, New Delhi, a premiere archive under whose aegis this large-format book is co-published as part of an impressive series marking a point of arrival for Indian photography as a serious field of historical investigation.

The authors take a biographical approach, not to declare Raja Deen Dayal as a great master but “to interrogate the institutional systems and practices that contributed to the development of his practice as well as to understand the frames of analysis through which he has been interpreted during his lifetime and in the postcolonial period [42]”. For these art historians, the disclaimer is important for bypassing questions of artistic originality and style and the burden of showing what is distinctively “Indian” about his work. They describe Dayal as a man of the marketplace. He establishes commercial studios first in Indore, then in Hyderabad, and offers a range of coloring and painting services, helped by a large staff of artists, including his sons and British photographers, who are identified as “operators” in the studio registers. Dayal is less the name of an individual artist and more a reliable brand name in the marketplace, recognized for “quality,” understood as an economic value based on the studio’s ability to offer a rich tonal range and sharp details through careful control of lighting and camera lens, whether the subject be a group sitting for a portrait, a panoramic landscape, or a ceremonial procession involving hundreds of people and animals on a busy street (34-37). His images also recirculate widely: images of the Hyderabadi Nizam’s territory and royal ceremonies end up not only in lavish albums for diplomatic gift-giving, but are also sold as individual prints, cheap souvenir booklets and postcards, and published as engravings in London-based illustrated magazines.

Importantly, we learn that Dayal’s staggering reputation in the field is not only a result of scholarship but also the self-aware cosmopolitanism with which he positioned his craft between British interests and those of the princely states he served. Chapter 2 attends to Dayal’s early career after graduating from the Thomason College of Engineering in Rourkee and joining the Public Works Department of the Central India Agency as a trained surveyor and photographer. With great insight, Dewan elaborates on the visual relationship between Dayal’s landscape photography of the Central Province and the procedures of land survey he learned at the engineering college. Survey, we learn, is a technique of measuring land and drawing maps for the purposes of building roads, railway tracks, and bridges. The diagram on paper requires a fine calibration of two key elements, a “baseline,” which is a horizontal extent of land measured from a commanding position, and “stations” or fixed vertical markers in the landscape, such as church steeples, prominent building, trees, all clearly positioned figures. In Dewan’s visual analysis, Dayal’s photographs appear with the clarity and eloquence of a well-coordinated map. In Indore, Dayal’s documentation of railway tracks and bridges, and archaeological sites such as the Buddhist stupa at Sanchi, celebrates not only the engineering feats of British designers but also the progressive outlook of the princely state that funded these projects in its territory, not to mention the trained eye of the photographer who serves both.

Carefully analyzing Dayal’s wet-stamps on prints and signatures on negatives, and tallying existing prints with negative numbers recorded in the artist’s studio registers, the authors construct an unshakable chronology and the thematic coordinates for the book’s seven chapters. Three appendices describe their systematic research procedures for determining the time lag between the shooting of a photograph and the making of prints for myriad, commercial purposes. Often an insight developed in one chapter illuminates a way of seeing photographs in another. In Chapter 7, for example, where Dewan compares the interiors of Hyderabadi palaces to Dayal’s landscape photography (203), we begin to see chandeliers, furniture, and sculpture like visibly distinguished “stations” within the clutter of those cavernous spaces.

Dayal puts his finely-balanced craft to full use in Hyderabad, the center of his commercial enterprise on which the book devotes most of its chapters. Chapter 3, by Hutton, discusses Dayal’s first major project as an independent artist, of documenting various sites in the Nizam’s dominions and selling thirty gorgeously-produced, leather-bound albums to the Nizam for diplomatic gift-giving. Chapter 4, by Dewan, focuses on the albums of royal and viceregal visits, followed by a chapter by Hutton on the Nizam’s hunting soirees. Chapter 6 discusses the elite culture of other Hyderabadi nobles. The book ends with Dewan’s chapter “Interiors and Interiority” that explores palatial interiors and bourgeois homes, as well as studio portraits, in Hyderabad and Bombay. One craves for a conclusion, but perhaps the volume is an invitation to further research and inquiry.

Importantly, the authors consider the “album,” rather than individual masterworks, as the primary unit of their analysis. An album asks us to consider photographs as fragments of a story that emerges only during the assembly and sequencing of images along with the turning of the album’s pages. When at its best, analysis of individual images leads not simply to their own iconography but also to the larger role they play within the album as a whole. My favorites are images whose significance remains unclear until we imagine them inside an album. For instance, in Chapter 5, on hunting scenes, a low angle view of a rocky hill titled “The Hanka to Dislodge a Wounded Tiger” confuses us at first (fig. 97). For Hutton, the image “embodies one of the primary experiences of the hunt: looking for a subject (the tiger) that is unseen” (160). Describing a hunt arranged for the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, in April 1902, when an attempt to dislodge a wounded tiger from a cave resulted in a man’s death, the imminent disaster is clearly staged. The chaos of beaters in the middle ground, and the webbed branches of leafless trees through which we see a lone figure standing exposed on the hilltop, only dramatize the imagined threat of the invisible beast.

When seen encountered amidst royal portraits and iconic views of dignitaries posing with bagged prey as trophies, unseen details of Dayal’s photographs acquire in these albums what we might call an icon-effect. In chapter 4, titled “Royal and Viceregal Encounters,” is a wonderful example titled “Viceroy Lord Elgin and Party Inspecting Photograph Album of Their Visit Produced by Raja Deen Dayal & Sons, Secunderabad, November 1895” (fig. 63). Except for the long caption, the image is unreadable because we only see the backs of a group of people, huddled around a low table in the background between two huge columns of the Chowmahalla Palace. Dewan writes that the image shows the “act of viewing” itself as an important part of the choreography of state visits (112). Within this scopic regime, Dayal organizes the anonymous group only to summon up an invisible album, as if it were an unseen tiger appearing within the visual structure of the image.

The authors’ pursuit of such hidden (self-reflexive, and subaltern!) icons within royal commissions leads to one of their most provocative speculations, namely, the figuration of modern subjectivity in Dayal’s work. The claim is made at least twice. Towards the end of her chapter on “Royal and Viceregal Encounters,” Dewan gathers a group of images that shows figures in transit, waiting for the arrival of royalty (fig. 78), or preparing for a shooting soiree (fig. 79). Dewan calls these “threshold spaces,” and reads in them the presence of bourgeois industrial modernity. As in 19th-century Paris, so here, she writes, “images of transitional moments and threshold spaces provide a meeting point between the courtly culture and an emerging modernity, via the medium of photography (131). “ To me, the reading is a stretch that only contributes to the very myth of Dayal that the authors had so diligently resisted throughout the book. More to the point, seeing photographs in isolation, as self-contained images of modernity akin to “French impressionist paintings,” weakens their role within the space and temporality of the albums of which they are a part.

In chapter 7, Dewan also posits a modernist relationship between architectural interiors and psychological “interiority” of the owners. She uses Walter Benjamin’s discussion of Parisian domestic interiors, where industrial products purchased at commercial arcades are assembled to signal the private realm of individual owners. To some extent, this relationship between domestic interiors and the “inner self” of individual owners may apply to middle-class homes in Hyderabad and Bombay (figs. 125-128), from which, however, the interiors of the Nizam’s palaces must be distinguished. Surely, Dewan’s use of “Palace Interior as Symbol of State” as a chapter subtitle (197) indicates her understanding that the palace interiors are not just marks of personal taste. These lavish interiors celebrate the Nizam’s glorious city. The Bashirbagh, we learn, was specifically designed as an architectural spectacle to entertain dignitaries, becoming “the most frequently photographed interior palace space in Hyderabad” (203). Yet, in the end, these palaces “represent the ‘self’ of the Hyderabadi noble as international aristocrat” (206). Moreover, the “self” also grapples with “traditional and modern” identities in a way that conjures up, through hindsight, the modernist preoccupations of 20th century India (203).

The treatment of “self” as a natural state of being, not a product of the marketplace, as Benjamin argues creates an inverse reading of Dayal’s studio portraits, with which the chapter ends. Unlike Benjamin, for whom commercial arcades and World’s Fairs played a central role in the enchanted self-fashioning and display in 19th-century Paris, the painted backdrops and high-end Victorian furniture in Dayal’s studios do not provide his clients fantasies of affluence, individuality, and privacy to take home. Rather, these props “brought the interior of the home into the interior of the photo studio, an overlap that asserted the studio portrait as a reflection of the inner self” (213). The belief in “inner self” not as a phantasmagoric spectacle but as a “psychological state” also leads to a literal reading of photographs. A cabinet card showing a seated Englishman scolding a dog (fig. 129) reflects “the sitter’s stern nature.... and the disciplinary nature of his job” (212). The slippage occurs in spite of the fact that Dayal’s clients commonly called his studio a “fairyland” (212).

The book invites us to engage with its many provocations. It also generously offers us high-quality reproductions to discover Dayal’s work on our own. We begin to wonder: Is the broken chair placed right in the middle of a banquet at the Bashirbagh accidental, or does it suggest another purpose, making Dayal’s photography serve as an obsessive inventory of the Nizam’s property (fig. 118)?[1] How could Dayal show a woman, fully lit and without a blur, standing behind a table in the far end of an enormous interior of the Chowmahalla Palace when we also learn that such views would have required long exposure time, lasting for hours (fig. 119)?[2] Finally, how much did Dayal manipulate his photographs? We know that he and his technicians retouched negatives and colored photographs. But in an unusual image, the Nizam on horseback clearly looks like a cut out (fig. 67). Did Dayal use combination printing, or photomontage?[3] In the end, this brilliant publication leaves us with a lingering thought that there is more to this artist-photographer that still remains hidden in the dark.

Ajay Sinha teaches courses on Asian Art as well as Indian Photography and Film in the Department of Art and Art History and the Film Studies Program at Mount Holyoke College. Email: [email protected]

Notes

See Carol Armstrong, Scenes in a Library: Reading the Photograph in the Book, 1843-1875 (The MIT Press, 1998) for Henry Fox Talbot’s view of photography as inventory. Dayal’s mode of picking out furniture and other artifacts inside crowded palace interiors as if they were “stations” in a land survey also itemizes them as in an inventory available for forensic uses.

In an email communication, Dewan identifies the figure as a statue of a woman holding a musical instrument. This may be true except for her extremely realistic appearance, with deep irregular folds of her lower garment also reflected in a mirror behind her. If it is a sculpture, it stands out in a space that is conspicuously devoid of paintings and other sculptures, unlike the Bashirbagh in fig. 123, for instance, which even includes a figure of an acrobat seemingly hanging from the ceiling in the distance and a stuffed bear automaton standing in the foreground. Moreover, in the context of these designed interiors, where unpainted marble and metal sculptures usually communicate the Victorian tastes of the Hyderabadi nobility, a painted sculpture is unusual. At the very least, the realistically painted figure functions less like a natural part of the palace décor and more like a tease provoking a vigilant eye into recognizing the master’s artistry.

On checking a comparable print at the Royal Ontario Museum for me, Dewan finds no indication of photomontage. But since contemporary commercial studios regularly used a huge arsenal of techniques – including vignetting, combination print, and photomontage, it is hard to believe that a shrewd and competitive businessman would not. See Shilpa Goswami, Deepak Bharatan and Jennifer Chaudhry, “Photographers, Studios, Processes and Formats,” in Allegory and Illusion: Early Portrait Photography from South Asia (The Alkazi Collection of Photography, 2013), 70-91. A study of the original negative might be in order here.