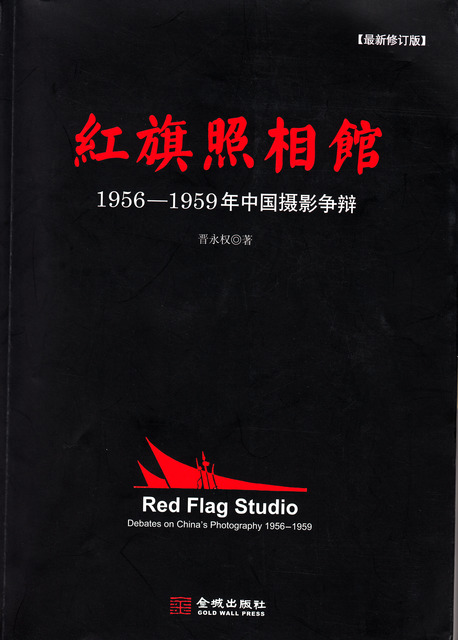

Jin Yongquan 晋永权, Hongqi zhaoxiangguan: 1956–1959 nian Zhongguo sheying zhengbian 红旗照相馆: 1956-1959 年中国摄影争辩 [Red Flag Studio: Debates on photography in China, 1956–1959] (Beijing: Jincheng chubanshe 2014) 303 p. ISBN 978-7-5155-0898-6

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

At first sight, Jin Yongquan’s book seems to confirm the standard narrative of photography in socialist China. Having named his book on news photography The Red Flag Studio, Jin seems to repeat a familiar story: press photography in socialist China was so heavily staged that it was no different from studio photography and was thoroughly controlled by the mandate of the government. But don’t be fooled by the title. Jin’s analysis of the socialist era is anything but clichéd. Jin portrays cultural workers neither as helpless victims of the state and party control nor as heroic martyrs whose perseverance led to discreet expressions of individual creativity. Jin’s narrative does not shun the horrors of state monitoring—the control, the regular purges, and the persecution. But he simultaneously demonstrates, in unusually vivid detail, that the tension in Chinese socialist photography was far from a simple, one-dimensional pull between party/state and innocent individual.

Jin presents this paradigm-changing narrative through five chapters. The first chapter focuses on the debates regarding the validity of “arranging and refining” (zuzhi jiagong组织加工) and “posing and staging” (baibu摆布) in news photography. The author introduces his readers to the complicated and heated debates that took place inside the official Xinhua News Agency through a few incidents when press photographers’ posing and staging was revealed and criticized by their own colleagues. Cases under discussion include Du Xiuxian’s photograph of the rental strollers at Beihai Park and Yuan Lin’s photographs of the No. 1 Automobile Factory, both of which had received great praise as successful examples of photo journalism before suspicion was brought to the methods of their creation. These fascinating examples do not lead only into an in-depth account of the theoretical debates; they also demonstrate the multilayered strains triggering and complicating these debates, such as the conflicts between the headquarters in Beijing and local branches, and between critics and practicing photographers.

The second chapter explores the self-identity of press photographers through the “Zuo Ye incident” of 1957. During an important diplomatic event at the National Agriculture Exhibition, Zuo Ye, then the assistant agriculture minister, scolded a press photographer who was pushing his way forward to get a good shot. Responding in solidarity, press photographers quickly launched a media campaign. Zuo’s behavior was criticized as a manifestation of the general bureaucratic obstruction of news reportage. However, the tensions that developed due to the Zuo Ye incident were soon conflated with the Anti-Rightist Campaign, a mass political persecution from 1957 to 1959. The most outspoken press photographers came under harsh state suppression when their articulate criticism of Zuo Ye was deemed an orchestrated, vicious attack against the Party. The author approaches this incident as a rare opportunity to tease out the contradictory nature of the self-image of press photographers and their social reception, which oscillated between prestigious cadres who were trusted by the Party to educate the masses and selfish craftsmen who indulged in materialistic comfort without a firm devotion to the socialist cause.

Chapter Three looks at how the work and life of press photographers were affected by the Great Leap Forward (1958-1961)—the economic and social campaign in which attempts at rapid industrialization and collectivization led to great famine. Jin begins his analysis with “Jumping for Joy on Top of the Satellite Harvest of Rice,” a photograph aiming to show rice fields growing with such incredible density that they could support the weight of four young children—as the title suggests—jumping on top. Jin examines the creation of this “most notoriously fraudulent press photo” and its wide celebration as a result of the media’s thirst for innovative representations of agricultural production. Jin contextualizes this photograph within the new expectations of press photography brought by the Great Leap Forward and photographers’ struggle to meet those expectations—this utterly ridiculous image is explained as a logical outcome of the collective pursuit for compelling reportage. Jin painstakingly points to the complexity of Chinese press photography even while the cultural milieu became increasingly hegemonic. He reads between the lines of the seemingly passionate public statements in materials such as Big Character posters and annual work reports to discern press photographers’ shrewd ways of passively dealing with the incessant political campaigns, for instance repackaging what they already did on a daily basis with the hyperbolic rhetoric of the Great Leap Forward. He also points to the genuine efforts of some press photographers to improve the effectiveness of their work, as shown for instance by their renewed interest in the techniques of portraiture. However, Jin concludes that the Great Leap Forward further consolidated regulations that were based on state policy and implanted by the Association of Chinese Photographers (Zhongguo sheyingjia xiehui中国摄影家协会). Jin illustrates the tightening control with the poignant story of Jia Huamin, a photojournalist working at China Youth Daily who was ruthlessly purged by his fellow photographers after he published in 1958 an unfavorable review of the Exhibition of Great Leap Forward Photography. The unanimous criticism of Jia reflected a newly ossified official stance on the meaning, significance, and aesthetics of photography.

The fourth chapter introduces the “rebels”—leading photographers or critics whose nonconformity with Party policy cost them professional prestige and the right to work. The chapter starts with a detailed study of Dai Gezhi, chief editor of Sheying yewu (The professional work of photography), the leading trade journal published by the Department of Photography of the Xinhua News Agency. Dissatisfied with the prevalence of formulaic works, Dai proposed shifting emphasis from the bland requirement of prioritizing the political to more nuanced technical concerns in the production and evaluation of photography. Dai’s story is followed by case studies of similar photographers such as Ding Cong and Chen Huaide. Jin analyzes denunciatory documents to reveal not only the twisted logic underlying these seemingly illogical rants but also the social mechanisms enabling the successful promulgation of denunciation. The majority of these rebels had enjoyed success and recognition under the Nationalist regime (1912-1949). Although for a short period these skilled professionals were assimilated into the new China, their disposition and style, even their prestige, came to be increasingly at odds with the new regime, which had already fostered a new generation of professionals in whom the militant discourse was second nature and who harbored a generational hostility toward the old authorities.

The last chapter looks at how Chinese press photography defined its own identity through various foreign others from both capitalist and other socialist nations. Jin starts the chapter with a detailed account of French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson’s 1958 visit to China. Although Cartier-Bresson was initially embraced by his Chinese colleagues for his open alliance with Communism, his famous motto of capturing “the decisive moment” quickly came into conflict with the prevalent practice of staging in Chinese photojournalism. To cleanse the bad influence Cartier-Bresson’s method might have cast in China, the Association of Chinese Photographers launched a campaign to criticize him. His photos, once applauded in China as both revelation and criticism of capitalist mores, were deemed to be “trivial accusations that are essentially of great help” to capitalism. China’s awkward encounter with the photography of the capitalist world is further analyzed through cases ranging from the regime’s triumphant debut in 1958 at the World Press Photo (the most prestigious press photography competition) to the precarious career of Xie Hanjun, a US-trained portrait photographer who had returned to China in 1956. The last section of the chapter turns to photography exhibitions and exchanges within the socialist bloc to demonstrate an equally contentious relationship between the dominant style of the Soviet Union and that of a relatively young Communist China eager to define its own stance against the “elder brother” Soviet Union.

Jin Yongquan’s Red Flag Studio distinguishes itself from other publications on the photography of socialist China by its focus on case studies and in-depth analysis. Jin approaches the 1950s Chinese press photographers as members of a nascent professional group that struggled to define its own identity, social position, and rules of self-regulation amid nonstop political campaigns. Jin recognizes that, despite frequent and brutal persecution, the majority of photographers were still productive members of the new state. The photographers did not function as slaves vulnerable to the political will of the party state. Instead, their professional aspirations, personal tastes, and specific circumstances had significant impacts on the way press photography developed. Even though the party/ state clearly wanted photography to function as propaganda, this general principle became vague and ambiguous when confronted by the nuts and bolts of photographers’ daily work. The faceless party state could not always offer a ready answer to the myriad questions photographers posed: What constituted a good propaganda photo? What was considered factual and valid in press photography? Would aesthetic concerns in news photography help improve its propagandistic effectiveness? If yes, what would be appropriate before one went too far as a formalist? By focusing on specific debates, Jin’s book reveals the intricate dynamics at play determining the ways by which individuals, units, or state officials responded to these questions.

The Red Flag Studio is rich in argument and at times dense in its incorporation of a vast amount of material. Jin offers such a lucid and suspenseful account that at times the book reads more like a literary work than an academic study. The many historical characters—not only the heroic, tragic ones but also the ones who went along with the campaigns and who remind us of Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil”—are skilfully brought to life. Jin’s balanced treatment of press photographers, fully empathetic yet determinedly unsentimental, probably partly results from his own background as a photojournalist. While Jin currently wears multiple hats as photographer, curator, and university instructor, he started his career as a documentary photographer and remains the head of the Photography Department at The China Youth Daily, one of the leading newspapers in China.

Jin’s position at The China Youth Daily has provided him with ready access to the archives of the newspaper, which contain personnel files and denunciatory materials normally hard to obtain. In addition, this volume is the fruitful result of Jin’s avid, decade-long collection of materials on socialist photography. Many of the key pieces of evidence in this volume were scavenged from second-hand bookstores or preserved from destruction by chance. For instance, Sheying gongzuo 摄影工作(Photographic work), a trade journal of only six issues published by the Bureau of News Photography in 1951, ended up in the corner of a lone used bookstore in Shijiazhuang, while Guanyu xinwen sheying zhenshixing wenti taolun de zongjiexing yijian 关于新闻摄影真实性问题讨论的总结性意见(Conclusion on the discussion regarding the factuality of news photography) was about to be dumped when Jin discovered it in a pile of construction garbage at a news agency. These rare materials enabled him to answer previously impossible questions.

Probably thanks to his own experience working in the Chinese media, Jin pays great attention to the interactions between the party state and the field of photography as well as those within the latter. The central news bureau, the Association of Chinese Photographers, the national newspapers, the local branches of these national newspapers, and local newspapers had different pressures, aspirations, and modes of operation. It is particularly worth noting that Jin has made painstaking efforts to investigate the aspect of social interactions, favors, and indebtedness that are pivotal to the operation of Chinese society but that are too often left out of the historical narrative. Jin collected materials relating to a specific debate in an exhaustive manner so that he could offer convincing interpretations of the participants’ intricate motives, based on careful reconstruction of the chain of events. Much of the evidence in this book comes in the form of denunciatory materials and confessions, twisted self-revelations written under pressure. Jin neither takes them at face value nor discredits them as false accounts, but patiently works through these difficult materials to arrive at his conclusions.

There are a few aspects of the book that allow room for improvement. Readers would certainly benefit from an introduction. Without an overview, it is not always clear how the various chapters fit with one other. The volume contains fascinating illustrations, but in numerous instances the relevance of these illustrations to the text is obscure. For readers, the urge to figure out the relationship between illustration and text distracts from the flow of the argument, which is all the more lamentable considering that the text is exceptionally lucid. While the author has a keen eye for images worthy of publication or reprint—press photos deemed unsuitable for publication and contemporaneous cartoons on photography—these valuable materials might have been better presented as a separate section.

Hongqi zhaoxiangguan won instant acclaim in China when it was first published in 2009, and its continued success led to a new edition in 2014. I sincerely look forward to the day when an English translation becomes available, ideally with added notes to aid readers with little background knowledge of socialist China. Jin Yongquan’s revelation of the complexities of press photography in China encourages us to rethink many of the broad-brush claims not only for Chinese photography but also for Cold War visuality in general. Hongqi zhaoxiangguan is a pioneer contribution and a must-read for anyone interested in Chinese photography or socialist visual culture.

Yi GU is an Assistant Professor, Department of Arts, Culture and Media, University of Toronto Scarborough, and Graduate Department of Art, University of Toronto. Her research interests include photography history and twentieth-century Chinese visual culture. Her email is [email protected].