The ‘China Dream’ Reimagined: Contemporary Photography in China

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Since late 2012, across the country the “China Dream” (Zhongguo meng) has been promoted as a slogan, taking the place of the “Harmonious Society” (hexie shehui), which was introduced by former president Hu Jintao in 2005.

According to Hu, a harmonious society is one that is “democratic and ruled by law, fair and just, trustworthy and fraternal, full of vitality, stable and orderly, and maintains harmony between man and nature.”[1] The idea of harmony has been central to the philosophical teachings of the major Chinese traditions, such as Confucianism and Taoism.[2] Hu’s public diplomacy terminology suggests that a rising China is not a threat to the rest of the world; rather, it is a stabilizer for global peace.

Now, the concept of a harmonious society has been relegated to the background in order for President Xi Jinping to develop the China Dream, which aims to demonstrate aspirations, both national and personal, for, he says, “sustained economic growth, expanded equality, and an infusion of cultural values to balance materialism.” He emphasizes that “[t]he great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is a dream of the whole nation, as well as of every individual.”[3] The actual meaning of the phrase is less concrete: “enabling people to project their own personal dream on the official concept” on the one hand; on the other, it “is also designed to help the Chinese leadership unite the Chinese people at a time of growing political and economic uncertainty.”[4]

These phrases are culturally engaged: although each represents a specific political strategy, both provide a new space for artistic and critical reflections.[5] The new model, “The China Dream,” projects a kind of unreality; it does not provide an exact direction, but instead, superficially, it offers a sense of direction. It forms a distance—ironically, a permanent one, never reachable—and, simultaneously, a romantic, even artistic distance. The intention is that the ultimate destination not be clearly defined; rather, it can be imagined and interpreted from a variety of perspectives. It is neither far from one’s current situation nor close to it, but it implies that the destination is only a dream away.

Said Xi Jinping, the China dream is “a dream for peace, development, cooperation, and mutual benefit for all. It is connected to the beautiful dreams of the people in other countries. The Chinese Dream will not only benefit the Chinese people, but also people of all countries in the world.”[6]

In the last thirty years, China has seen extraordinary economic development and the rapid urban transformations.[7] Along with the traditional means of holding on to the present appearance, artistic strategies are being created in response to the overwhelming pace and extent of change in contemporary China. The constant changes have shaped a moving reality beyond the normal and tangible environment of daily life. Capturing and interpreting this reality—what may be thought of as the image of the China dream—requires new artistic techniques, and photography has risen to the challenge.

Manipulation is a key strategy to extend this almost illusive experience and, at the same time, to critically examine the nation’s urban development. Digital technology provides the means to broaden involvement and critical thinking by way of visual narratives. From the numerous possibilities within the digital process of photographic production, images can offer a quality of ambiguity regarding the real and the unreal. As William Mitchell writes: “We must face once again the ineradicable fragility of our ontological distinctions between the imaginary and the real, and the tragic elusiveness of the Cartesian dream. We have indeed learned to fix shadows, but not to secure their meanings or to stabilise their truth values; they still flicker on the walls of Plato’s cave.’[8] Here, with or without digital technology, the dramatic conflicts, struggles, and triumphs inherent in the cities’ continuous growth are central to the China Dream, not only to reinterpret personal experience in everyday life, but also, and more importantly, to form critical views about the urban development.

The Spectacle of Prosperity

The China Dream, understood within the current narrative of Chinese public diplomacy, in general, can be seen simply as a lofty image—a spectacle—of extraordinary achievement by one of the world’s largest economic powers in just a few decades. This “spectacle” has been suggested by numerous urban billboards, designed often with combinations of political symbols and futuristic cityscapes. The character “meng” (dream), usually in calligraphic style in the center of a billboard, gives substance to the strategy whose goal is a future fantasy, or somehow, strangely, it is as if it reiterates the “inactuality” of what China is, and of what we are experiencing. But even before anyone came up with “the China Dream,” the astounding economic development has been observed and critically discussed by artists since the country’s rapid urbanization, at the beginning of the millennium.

Since 2001, the artist Miao Xiaochun (b. 1964) has used his camera to reflect the intensive urban changes in the capital city of Beijing. His wall-filling Celebration (2004; see figure 1) looks like a simple record of an opening ceremony for the SOHO real estate company, a representation of an enormous celebratory assembly in a contemporary cityscape. In fact, Miao’s digital skills enabled the artist to discreetly maximize the number of participants in the picture, which was constructed from more than ninety individual shots. With careful reading, one can discern repetitive details: for example, a group of workers wearing yellow helmets surface in several locations. They move, come and go, but were all recorded at different moments.

For Miao, photography can hold on to a single instant, but also to a longer span. In another example, Surplus (2009; see figure 2), he juxtaposes two buildings of entirely different styles and with different functions: on the left a disco club with a fashionably Westernized façade and on the right a Chinese restaurant with a traditional appearance—an imitated modernity side by side with a fake tradition. In this case, the location of the two constructions has not been artistically or digitally manipulated: it is real. However, digital technology enables the artist to come close to the possibility of human vision in re-interpreting and bringing into focus the details of the image. As Jansen explains: “By combining numerous photographs digitally at the computer, Miao simulates the eye’s way of working, simultaneously destroying the illusion of an authentic representation of reality.”[9] To immerse oneself in the theatrical events presented in the photograph, one could explore and imagine the stories taking place inside each window and the ways to consume the “surplus” energy and excitement of the day. The celebratory atmosphere of such “prosperity” is clearly an ironic interpretation of the “China Dream.”

With extraordinary speed, China has constructed thousands of high-rise buildings for the millions of people who have been relocated or who have migrated from the countryside, and reshaped the skylines of its major cities. According to a recent report in Foreign Policy magazine, “Chinese officials hope to link Guangzhou, already home to nearly 12 million people, and its sister cities in the Pearl River Delta, to create a ‘mega-city’ of 42 million inhabitants spread across 16,000 square miles.” Chongqing, a municipality with thirty million people, “constructs 700,000 units of public housing annually, with 430 million square feet due to be completed within the next three years alone”; and “although Shanghai had no skyscrapers in 1980, it now (in 2012) has at least 4,000—more than twice as many as New York.”[10]

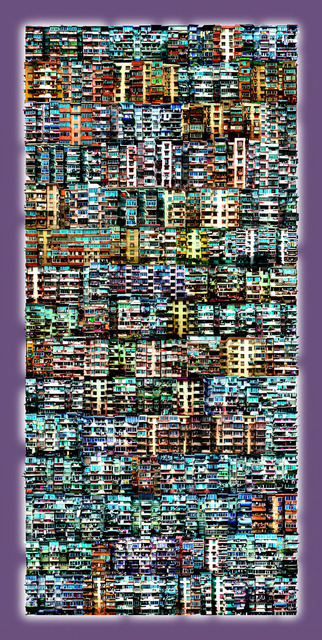

All post-1980s residential high-rises have a similar appearance, with little individuality in style. This unadorned form of architecture, with its obvious functionality, has become the economic model for residential building throughout China, and the focus of the work of Xiang Liqing (b. 1973). It seems to be the most dependable visual product made by the Socialist-planned economy since the nation’s Open Door Policy, and represents the social status of the majority of people. In Xiang’s series Never Shaken (2002; figure 3), his housing blocks look simple and modest, representative of most of the newly built homes for low- and middle-income households. The buildings are visually concentrated and reinforced, unit by unit, window by window, accumulating collectively to form a “super-tower”: a high-density home. Although the apartments are closely connected to one another, the images do not present any sense of intimate neighborhood; instead, they hint at a rather unpleasant environment, such as an overcrowded jail. Households have no choice but to conform and accept this new iteration of “collective space,” to go from the traditional courtyard lodgings and, later, in rural areas, the Socialist people’s communes to a contemporary “residential spectacle.”

Jiang Zhi’s (b. 1971) Rainbow series (2005) is another “spectacle,” seemingly a “natural spectacle.” In it the artist depicts an urban reality dominated by consumer culture and commodity fetishism as an ironic fairy tale in which a splendid rainbow traces an arc across the sky above Tian’anmen Square (figure 4). The image of the rainbow is perfectly symmetrical according to the architectural arrangement of the square, too symmetrical to be true. The rainbows consist of images of hundreds of neon signs, both Western and Chinese, sourced from across the city, ranging from those of fast-food restaurants, household products, and news media to those of theaters, shops, clubs, and banks—in fact, representing almost every kind of commodity one would expect to see on the street.

The details contained with the artificial rainbow require a careful reading. Neon lights belong to our cities and are associated with the prosperity of urban life. In Jiang’s work, with their strategic, seductive power blinking on top of buildings, these interconnected lures keep forming and nourishing our urban desires. The natural phenomenon of a rainbow—according to Genesis, the sign symbolic of God’s covenant with Noah and his descendants—has been replaced by a man-made spectacle formed from fragments of urban highlights: a fantasy of earthly possessions. According to Jiang, the rainbow “is constructed as a surrealistic prospect, representing commercial consumptions that take place every day on the way toward the future. When all cultural and spiritual values have disappeared or been lost through urban development, then the pursuit of the material becomes the sole impetus in contemporary life. The previous utopian ideology is transformed into consumeristic ecstasy and greed, which can still be romantic, as ever.”[11]

Jiang Zhi’s rainbow, bearing its multicolored icons, is no longer an assurance of living beings being saved from a flood, but instead a celebratory firework commemorating economic success, or a sequence of flares warning of the coming flood of urban desires.

Perhaps nothing could be more spectacular than the realization of the Three Gorges Dam project, which spans the Yangtze River, a dream for many generations. Since it was originally envisioned by Sun Yat-Sen, in the early twentieth century, despite being mired in controversy,[12] the project finally received approval by the National People’s Congress in 1992. Two years later, on December 14, 1994, construction commenced in Sandouping in the city of Yichang, Hubei Province, with the aim of building the world’s largest hydropower station. The spectacle of the dam project and its environmental, social, and cultural impacts have become popular motifs in contemporary photography.

For Chen Man (b. 1980), the camera lens is an instrument for collecting primary visual information, which is then reassembled through advanced digital techniques that offer infinite possibilities. As the artist puts it: “I don’t see a photographic frame in the conventional terms of composition, light and moment. You could say it sets the stage for the story that I create around the image.”[13] In a series dating from 2009, a row of unidentified teenage girls, or, as the title indicates, (Communist) “Young Pioneers,” dance confidently in the wind on top of the newly constructed Three Gorges Dam, as if it has become their stage (figure 5).

When Chen Man takes photographs, her “stage” is strictly private: no one is in attendance except for the performers and herself as director. The audience waits outside her “theatre” and is invited to glimpse only periodic views of the show—still images of selected moments. These fragments are connected by the audience to form a sequence of visual narratives. In Chen’s work, these narratives seem to be born in an imaginary visual world rather than captured from reality. Photography is a perfect medium for her to balance the natural and the artificial, the ordinary and the ideal, the remembered and the actual; her aesthetic approach reflects afresh on the reality, creating a “spectacle” of the “spectacle.” But, this powerful spectacle is certainly not a dream for those millions of people who had to endure relocation.[14] Behind such a grand image of the Three Gorges Dam, there is another “spectacle” formed by the numerous stories of forced migration and critically reflected through photographic practice.[15]

Desire for Power

In addition to myriad illustrations of significant economic growth, the government’s need for political and cultural power is visually apparent in everyday life. In the realm of art, contemporary practitioners have created hybrid urban settings shaped through photographic manipulations that result in dreamlike cityscapes that humorously feign the ambitious visions of contemporary China.

The artist Qiu Zhijie (b. 1969) has captured a series of images titled The Dream, which features versions of some of the most recognizable examples of world architecture somewhat surprisingly relocated to the county of Fuyang, in northwestern Anhui province (figure 6). For instance, the White House, the home of the president of the United States, is not rendered as just a smaller-scale version of the original; it serves as the prefecture-level government house in Anhui.

Fig. 6. QIU Zhijie, The Dream: Yingquan District Government House, Fuyang, Anhui Province, 2007, © Qiu Zhijie.

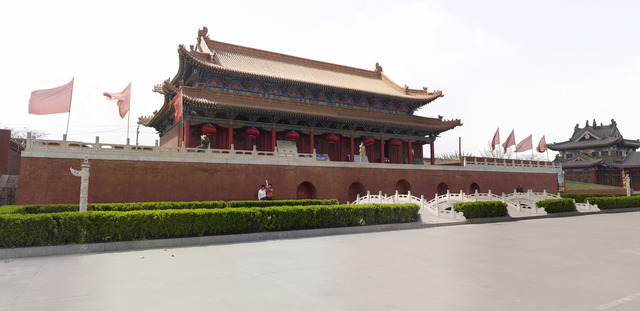

Fig. 6. QIU Zhijie, The Dream: Yingquan District Government House, Fuyang, Anhui Province, 2007, © Qiu Zhijie. The photograph consists of many individual shots assembled to maximize image resolution and thus invite close observation of every detail, such as the title of the book that covers the face of the reader seated in the foreground. As the series title indicates, on the one hand, the architectural appearance of the structure reflects the local government’s dream of power; on the other hand, for the visitor the scene represents a fantasy through a disorientating journey. In other images from this series, the buildings he chooses serve no practical function. Among them are models of Tian’anmen— the entry point to the former imperial palace of the Ming and Qing emperors and where Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China, on October 1, 1949.

Many models of Tian’anmen, authorized by local officials, are located outside Beijing: to name a few sites, in Yinchuan, of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region; in Suizhong, Liaoning province; in Baoji, Shaanxi province, in Huaxi, Jiangsu Province; in Linfen, in southern Shanxi province, this one captured by the artist (figure 7). Each is usually a miniaturized mock-up, as can be seen in fig. 7, with the proportion of the architecture in relation to the people in front of it is quite unlike that of the original. These fake Tian’anmens play a role as public sculpture, or as monuments (possibly temporary). They often act as a backdrop for photos of residents and visitors, similar to painted backdrops of popular scenes used in Chinese photo studios from the 1950s through the ’70s, such as the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge and the Monument to the People’s Heroes.

Rather than being flat pictures, however, these are three-dimensional buildings, and, regardless of the quality of construction, they are more realistic and more theatrical, and create strange new public spaces. They are not part of any theme park, such as the famous Splendid China (Jinxiu zhonghua) or its sister park, Window of the World (Shijie zhichuang), in Shenzhen, both of which contain collections of scaled-down national and international sites and attract visitors from all over China.

In order to see many tourist sites concentrated in one place, domestic travel is required. These Tian’anmen installations, however, are found throughout regional China, and often right in the center of a town: in other words, the sites have traveled to the viewers and become part of local life. To be photographed standing in front of a replica of Tian’anmen cannot prove that the subject has been on a trip to Beijing, but it serves as a visual statement. The image manifests not only a relationship between the photographed person and the authentic cultural architectural entity, but also one that pertains to the historical and political significance of that relationship. Any mock-up that bears even the smallest resemblance to the original can provide easy access to the power associated with it as a nationalistic symbol.

In his 2004 series Somewhere, Hu Jieming (b. 1957) appropriates images from postcards around the globe and fabricates new scenes. The photographs feature some of the world’s most famous tourist sites but at the same time, through digital manipulation, they appear to be of unknown places. For example, in the middle of Tian’anmen Square, instead of finding the Monument to the People’s Heroes and Mao’s Memorial Hall, there are a mausoleum—that of the Sphinx—and the pyramids, right on the central axis (figure 8). The image of the square must have been taken from the balcony of Tian’anmen, or as seen by the dignified gaze of Chairman Mao looking out from his portrait hanging above the Tian’anmen Gate. The individual components of the image on the site are all perfectly real, including the Golden River Bridge in front of the gate, pedestrians, traders, tourists, cyclists, and the late-1980s-style buses passing through Chang’an Avenue . . . until the eye reaches the Egyptian complex, which merges into the background. The gaze of Mao Zedong continues to look out over the country and his people, and extends its sight into the world for global “harmony,” or, in fact, chaotic coexistence. In another example, the Nine Zigzag Bridge in Yu Gardens in Shanghai leads visitors beyond the pavilions in the lake toward the skyscrapers of Chicago only a few miles away (figure 9). Both works function as images of everywhere but nowhere.

Similarly, Chi Peng (b. 1981) invites the viewer to embark on a confusing journey within one photograph (figure 10). The Day After Tomorrow (2005) features a bird’s-eye view of Manhattan, but beyond the city, an even greater force of urban development seems to be approaching. At the skyline, there are many of China’s landmark buildings and skyscrapers, such as the Oriental Pearl Tower and Jin Mao Tower (Shanghai) and the Bank of China Tower (Hong Kong). The unexpected arrival of these gigantic architectural structures in the distance forms powerful waves that appear set to replace the existing buildings, and suggests the “changing landscape” of the world’s economic and cultural center in the near future. A group of young men (or one man multiplied—in fact, the artist himself, naked, with pairs of dragonfly wings) take off across the expanded or reconstructed urban space toward the oncoming waves. In Chi’s imaginary world, the angel-like creatures are not afraid of the power of this urban revolution; on the contrary, it is as if they are flying over to greet the waves and to embrace and celebrate the moment of change.

Reinventing the Past

In his New Democracy (1940), Chairman Mao wrote that there can be “no construction without destruction” (bupo buli). It became an axiom for his Cultural Revolution, half a century ago, but may also be considered a prophecy regarding today’s dramatic urban development. Construction (jianshe, or jianli) in China does not constitute merely an effort toward improvement; it is a revolutionary action to replace the “old” with an entirely “new” visual environment. In the last thirty years buildings, complexes, streets, even whole large urban structures have been removed, reconstructed, or replaced, leaving little trace of what once was. For many, this is cause for celebration; for others, it generates grave concern for the cultural loss and nostalgic dreams for the past.

In light of the endless urban construction, Beijing-based artist Yao Lu (b. 1967) sees his city differently. At first glance, his works seem to be inspired by the traditional literati art, and his New Landscapes appear to present shanshui (literally, “mountains and water”) in the literati style of landscape painting suffused with reclusive propositions and a poetic mood (figure 11). On closer observation, however, the viewer sees that the landscape images are in fact ruins composed of mounds of rubbish covered with green or black dustproof netting, of the kind found on construction sites in every big city in China today.

The artist composes the scenes digitally and transforms them into mountains with rivers, clouds, trees, and pavilions in the manner of “blue-green” landscape painting. The current social and environmental upheaval does not bring excitement to Yao Lu; on the contrary, it invokes feelings of loss. The present, he says, “becomes a reality filled with endless opportunities for construction and change, yet, at the same time, catastrophic destruction and reconstruction. No one cares about this reality, nor is there any control that could possibly slow down the pace of its development. Envisioning the disappearing, at the center of my work lies a sense of melancholy and nostalgia, quite helplessly.”[16]

Through the artist’s digital manipulations, the dustproof netting not only conceals a disturbing environment—the ugliness of daily life—but also shapes a representative visual element—wastes on working construction sites—in China’s urban transformation. The mounds of rubbishes have been transformed into aesthetically pleasing forms. Although working with some of the most advanced cameras and forms of digital technology, Yao Lu fabricates a “reclusive” image, a spiritually peaceful world beyond secular life.

His works offer a vision of humanistic scenes representing the literati mood and poeticism in a way that turns out to be engagingly ironic. But the aestheticism can be tasted only as a sugar-coated pill. The capsule encloses the bitterness of the artist’s sense of loss, as well as his criticism of the cultural memory that has been collapsing from the weight of the urban structures of present-day China.

If Yao Lu reinvents a traditional aesthetics with today’s ruins, then Wang Chuan (b. 1967) searches for traces of the past in everyday reality. The eight great sites of Beijing (Yanjing bajing) were initially identified during the early Jin dynasty, in the late twelfth century. They were modified over the generations and authenticated by the Qianlong emperor (reigned 1736–95), to best represent the temperament and vitality of the imperial city.

The original sites no longer exist; they have been removed or rebuilt, and can be imagined only through historical literature. For example, one of them—Jintai xizhao—designated by the emperor based on the geomantic acknowledgment of its natural environment as a divine place for imperial tombs, is now part of the Central Business District in Beijing, the world’s fastest-developing city, known for the skyscrapers of SOHO and the CCTV headquarters. (figure 12) Nothing remains to attest to its past life, nothing except for a lonely stone tablet inscribed by the Qianlong emperor. When Wang Chuan visited the eight locations to photograph what could be seen there, he was struck by the vast discrepancies between historical description and today’s reality.

“I am frequently trapped in a rather conflicting situation,” writes the artist. “[W]hile recognizing those new things, as well as changes brought about by social development, I cannot help feeling confused about the changes accompanying such development. Many things that used to help us find the links between the outside world, the past, and ourselves are disappearing or being replaced. . . . Scenes filled with history and specific meanings are either diminishing quickly or existing in a super-realistic and isolated manner—separated from our life, or existing in real life without its original meaning. However, we still coexist with them, or even enjoy them.”[17]

Wang’s 2013 series Colourful extends his concern regarding disappearing cultural legacies and explores the awkwardness of the mock-ups of the original fragments: for example, stone carvings of dragons, unicorns, and lions, all roughly fabricated as false traditions, to decorate government buildings, courthouses, and restaurants, and as insignificant visual tags, situated amid ongoing urban development. The exception in the series is an image of a memorial archway, built during the Qing dynasty, with a wall constructed to protect the relic (figure 13). The inscriptions on the archway have been pixelated, rendering the structure’s significance unclear. However, the large characters on the wall, as a slogan, flatter this new political concept with an alternative proclamation: “Let dreams rise from here.”

The dreamlike experience of the urban changes has led the artist to develop a particular method for his work. It consists of neither a crisp photographic capture nor a virtual realization of an imagined past, but rather is a series of blurred images with pixelated details, appearing like unwanted traces of the mechanical process, resisting the artist’s hand. In fact, though, the pixel is the language. In our digital age, pixels—as technically important tools of mass communication—enable an image to be easily compressed and transmitted; more or less the whole world can be recorded or reinterpreted through a pixel-comprised reality.[18]

Trained as an illustrator, Wang does not rely solely on digital technology to generate pixels automatically by compressing images; he also paints them. For today’s digital-era artists, pixels are more than square-shaped, mechanical, cold replacements for the round grains of photographic film that reveal certain limitations. They are a new form of visual vocabulary with a particular aesthetic orientation to be appropriated, expressed, and accumulated, like traditional brushstrokes on a semi-abstract canvas. Rather than using pixels to obscure original parts of his images, Wang intentionally highlights what is obscured. What do we really see when we view Wang’s printed work? a blurry photograph with hundreds of thousands of pixels? or a precise depiction of a dreamlike, uncertain reality?

In the Chinese social and cultural context, the language of pixels has been developed into a conceptual proposition to reflect the distance between historical and contemporary existence, and the distance between the lives that we experience from one day to the next.

A dream is timeless: it can relate, usually visually, to the future or to the past, as long as it has distance from the present. It is essentially time-based: that is, it offers little possibility to be replayed. However, a dream can be “photographed” through digital manipulation.

Engaging with today’s China, during a period of immense change, artists have been critically reflecting on the “spectacles” of established economic prosperity, the increasing desire for political power, and, at the same time, the disruptions to cultural heritage caused by rapid development —all toward achieving the China dream. The “inactuality” of everyday life, or, indeed, the “dreamed” existence of beauty in the distance, is a mine of inspiration that is generating creative power in contemporary photographic practice.

Professor Jiang Jiehong is Director of the Centre for Chinese Visual Arts at Birmingham City University. Recent curatorial projects include The 4th Guangzhou Triennial: The Unseen (2012) and The 3rd Asia Triennial Manchester: Harmonious Society (2014). His latest book is An Era Without Memory: Chinese Contemporary Photography on Urban Transformation (Thames and Hudson, 2015).

Notes

Cited in Gao Hui (2006), Nuli goujian shehui zhuyi hexie shehui (Striving to Build a Socialist Harmonious Society), available at http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64156/64160/5121516.html.

Delury, John, ‘“Harmonious’ in China,” Hoover Institution Policy Review no. 148, 31 March 2008.

This has been widely quoted, in, for example, the Chinese Communist Party’s official newspaper, the China Daily, available at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013npc/2013-03/18/content_16315025.htm (accessed July 3, 2015).

d’Hooghe, Ingrid, China’s Public Diplomacy. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2014, 83.

For examples of artistic reinterpretations, see Jiang Jiehong (ed.), Harmonious Society: Asia Triennial Manchester 2014. Manchester, UK: Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art, 2014.

China Daily, available at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2015twosession/2014-03/05/content_19531184.htm [accessed on 3 July 2015].

This essay contains extracts from my book An Era without Memories: Chinese Contemporary Photography on Urban Transformation, published by Thames and Hudson (London) in spring 2015.

Mitchell, William, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992, 225.

Jansen, Gregor, “Post-History’s Beijing Just So,” in Uta Grosenick and Alexander Ochs (eds.), Miao Xiaochun 2009–1999. Cologne: Dumont, 2010, 127.

Groll, Elias, “The East Is Rising,” August 13, 2012, available at foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/08/13/the_east_is_rising.

Interview with Jiang Zhi, conducted by the author, October 26, 2007, online.

Lin Yang, “China’s Three Gorges Dam Under Fire’, Time, available at http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1671000,00.html (accessed on 4 July 2015).

Interview with Chen Man, conducted by Karen Smith, March 2009, published in Chen Man: Works 2003–2010. Hong Kong: 3030 Press, 2010, 28.

According to China’s official report, the number of migrants from the Three Gorges project is estimated at 1.2 million, accounting for only (!) 4 percent of population of Chongqing Municipality; see Li Jinhui, “Three Gorges Migration Not the Largest in Chinese History,” available at http://www.china.org.cn/english/2002/Aug/38581.htm (accessed on 5 July 2015).

For example, A Sunken Homeland, by Yang Yi, and The Empty City, by Chen Qiulin, which I discuss in An Era without Memories, 158–70.

Interview with Yao Lu, conducted by the author, 23 December 2009, online.

The German photographer Thomas Ruff similarly discovered that everyday images downloaded from the Internet at a low resolution could be developed to obtain a painterly or impressionistic quality when deliberately enlarged far beyond their photorealist tolerance.