Photographic Manipulation in China: A Conversation between Fu Yu and Gao Chu

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Gao Chu is a scholar of Chinese photographic history and a curator. His primary research interests lie in the visual archive of the Chinese revolution and Chinese photographic images in overseas collections, and both are the subjects of his current curatorial projects. Fu Yu is a Beijing-based photographer who has held several influential solo exhibitions and won photography awards in China.

Gao and Fu are good friends. The differences in their interests and expertise—one a historian with a special interest in Chinese photography during the Sino-Japanese War and Mao’s China, the other a contemporary photographer familiar with Western photography history—epitomize represent the varied attitudes that exist about photographic authenticity, the history of Chinese photography, and the relationship between the two. Gao Chu invited Fu Yu to participate in a conversation anchored in the topic of photographic manipulation.

Both are fully aware that, in addition to their agreement and disagreement on particular issues, their conversation is at times carried out as if they were talking from different frames of reference. They recorded the conversation and in the transcription have retained its informal nature in order to provide a glimpse into the wide variety of resources through which a new generation of Chinese photographers and photo historians understand photographic manipulation.

Gao: Let’s start with the question of authenticity in photography. The discussion of authenticity goes beyond photography. However, it has become one of the most discussed topics in Chinese writings on the subject. Debates on the authenticity of photography spanned the years of the War of Resistance [1937–45; also known as the Second Sino-Japanese War] and the early decades of the People’s Republic of China.[1] At the same time, modification of photography has been a common phenomenon. For example, photographs featuring Mao Zedong, many now iconic works in Chinese photo history, were frequently altered.

It’s worth noting that the modification and the dissemination of photographs were entangled processes. Whereas some modifications were made by photographers, others were done by those involved in the display and publication of photographic images.

Wartime photography was often made under limiting circumstances. Many battles took place at night, making it difficult to create a photographic record. It was a routine procedure to take a photo of the troops marching through the city gate in daylight. The publication of such photographs in Communist pictorials served as proof that our army [the People’s Liberation Army] won the battle and had conquered another city or town. Ideally there would be a plaque, bearing the name of the city, conveniently hanging above the gate so it would be evident which place was conquered. This is the phenomenon of taking a make-up shot (bupai 补拍) in daylight of troops entering a city.

Some examples of iconic photographs of Chairman Mao Zedong that were manipulated are:

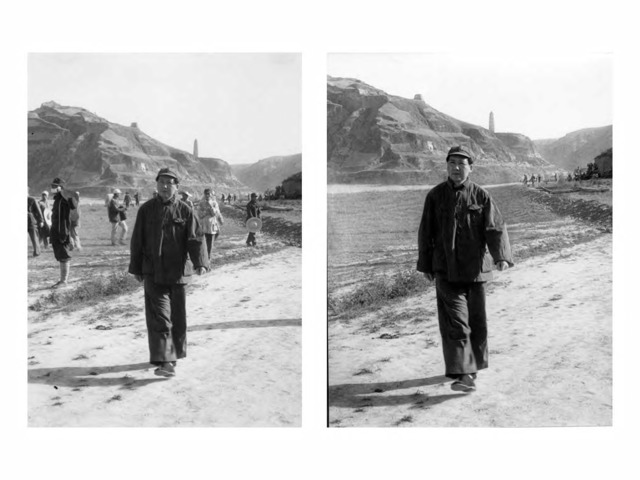

Fig. 1. Wu Yinxian, Under the Pagoda Mountain, 1942. The other figures in the field, except for a few in the remote background, are eliminated to highlight Mao Zedong.

Fig. 1. Wu Yinxian, Under the Pagoda Mountain, 1942. The other figures in the field, except for a few in the remote background, are eliminated to highlight Mao Zedong.  Fig. 2. Gao Fan, Mao Zedong and Zhu De in an Automobile during a Military Review at the Xiyuan Airport, 1949. The person standing next to Mao has been erased.

Fig. 2. Gao Fan, Mao Zedong and Zhu De in an Automobile during a Military Review at the Xiyuan Airport, 1949. The person standing next to Mao has been erased.  Fig. 3. Wu Yinxian, Mao Zedong’s Review of the Military in Yan’an, 1944. Zhu De, on the far left, is excluded in the process of cropping.

Fig. 3. Wu Yinxian, Mao Zedong’s Review of the Military in Yan’an, 1944. Zhu De, on the far left, is excluded in the process of cropping. Fu: Photography itself is a process of selection. So is the cropping during postproduction. Both types of selection alter photographic representation, sometimes quite dramatically. If a random shot of a street crowded with people captures a young girl and an old woman, there’s nothing special about it. But if the photographer frames the scene of that young girl and the old woman passing each other excluding everything else, then here comes meaning: Critics would then come up with different interpretations regarding life, growth, and aging.

The phenomenon of reenacted shots of troops entering conquered cities as you mentioned is indeed not a big deal in photography. Strategies like that are often adopted. Photography is more “Let me tell you” rather than “The reality is there and let’s take a look together,” or “This photo represents reality and let’s take a look together; what I saw is exactly what you would see.” No, it’s never been like that.

The iconic photograph Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima is a posed shot, even though the photographer repeatedly emphasized that the only change he made was to replace the original flag with a bigger one. Well, a bigger flag is nevertheless a deliberate choice for the shot. Another case is Raising a Flag over the Reichstag.

That photographer carried a flag in his bag after seeing Iwo Jima. Such actions are totally accepted in the field of photography. There’s no need to make a fuss.

To crop a figure out of the frame, as you mentioned, is fairly common as well. It’s part of what photography is, as there’s no clear line between what’s proper to do and what isn’t.

Gao: Let’s shift to the issue of “being present.” Those who consider themselves photojournalists are generally keen to be present when an event or an incident occurs. The first shot might not be ideal and it would be fine to do a posed shot afterward, but they’re still keen to be “present.” For example, Shi Shaohua [1918–1998], a renowned photographer who held such important positions as chairman of the Association of Chinese Photographers and director of the Xinhua News Press, explicitly made such comments in his writings in the 1940s and fifties.[2]

Fu: In fact, this isn’t a problem in photography but could be regarded as an issue in journalism. One fundamental fact of photography is the presence of a subject in front of a camera. The existence of the photograph indicates the presence of objects and events—that is, unless the image is a photogram, though surely that’s also evidence of presence. This is probably the only kind of objectivity that photography can lay claim to.

Gao: “The presence of subject in front of camera” could be what really had happened but it was made through a posed shot due to either inadequate conditions of the first shooting or the mere intention to make a better-looking picture, or, alternatively, fanciful creations such as the famous photo by Yu Chengjian taken during the Great Leap Forward [1958–61]. What’s your take on these different situations?

Fig. 4. Yu Chengjian, Jumping for Joy on Top of a Rice Paddy That Is a “Satellite Harvest” of Rice, 1958. The photograph was taken to demonstrate that the rice paddy was so thick it could support four children jumping on top of it. This is one of the most famous images coming out of the feverish reports of fake harvests during China’s Great Leap Forward.

Fig. 4. Yu Chengjian, Jumping for Joy on Top of a Rice Paddy That Is a “Satellite Harvest” of Rice, 1958. The photograph was taken to demonstrate that the rice paddy was so thick it could support four children jumping on top of it. This is one of the most famous images coming out of the feverish reports of fake harvests during China’s Great Leap Forward. Fu: This is not the problem of photography. Faking situations can’t be blamed on photography. Ever since the invention of photography, if you choose to believe that photographs depict reality, it suggests you don’t understand photography very well or that you’re gullible. Without text, a photograph can prove nothing. Take one photograph as an example: a smashed car that is upside down on top of another car, surrounded by a mess of random objects. If you saw the photo after a tsunami had hit, you would know instantly that the photo was about the tsunami. Indeed the caption would prove that to be the case. If you saw the photo by itself, without such a context, however, you’d wonder what it was about.

Therefore, photographs can be only secondary evidence, since the same photograph can generate a variety of interpretations. Even when we hold on to a photograph as evidence, we need some other proof to show that the photograph is credible. By itself, a photograph can’t prove much.

Gao: This reminds me of the well-known photo of the Great Wall by Sha Fei. When people went to the site to investigate, they realized that the guns in this compelling image were actually pointed toward the inside of the wall instead of the outside. Sha Fei’s arrangement creates an aesthetically powerful image, but it’s exactly opposite to the symbolic meaning the photo is meant to convey.

Fu: What matters is the photograph—and its caption—not any on-site investigation. Such investigation rarely matches the photograph, the viewer’s imagination, or the caption.

Gao: In my study of Communist photographers who were active between the 1940s and the 1970s, I’ve found that they never stopped discussing the truth value of photography during the war era. These discussions expanded after the establishment of the PRC. They were keen to define parameters for their profession. But based on your understanding, does it mean that what these photographers discussed wasn’t really about photography but, rather, about the journalism they engaged with?

Fu: Yes. We have to look at these discussions from the perspective of the time. What photographers did during the forties and fifties—cropping someone out of the picture, for example, or rotating the direction of the guns—led to the creation of photographs that are different from reality. But these photographs are in accordance with the photographers’ ideological stance and that of their colleagues, and that of the viewers. If looked at in this way, those photographs are truthful. But seen from the perspective of people with a different ideological stance, what they did is faking it. Now times have changed. We shouldn’t judge what happened then by our current standards. Photographs of that era should be viewed with the aspirations of that era in mind.

Gao: What about the photographs that were made for the purpose of anthropological study or social surveys, such as those made by Zhuang Xueben [1909–1984].[3] Do his photographs reflect reality in a relatively objective way or are they no more than “secondary evidence”?

Fu: When you compare an object, a piece of clothing, for example, with what’s captured in a photograph by, say, Zhuang Xueben, it’s likely that when looking at the actual article you would say, “Oh, so this is what this pair of shoes looks like! It’s a bit different from what my imagination drew from what I observed in the photograph.”

Nevertheless, photography helps. Without a photograph, it’s difficult to visualize something based on a description. It becomes relatively easy with a photograph.

When it comes to an actual photo, the same scene could lead to an entirely different photograph from a different photographer. You could almost see Zhuang Xuben the person through the kind of photographs he took. He must have been taking photographs in a calm, thoughtful, relaxed manner. The surrounding context must have been fairly quiet, which is quite different from our vision of the act of photographing as hyperactive, involving constant climbing up and jumping down, standing up and squatting down.

Gao: There are many versions of photographs of Mao Zedong in Yan’an that are the result of continuous manipulation. The different versions were made partly due to political demands and partly due to the photographers’ own pursuits, as it was the photographers who made the various changes.

Fu: In this process, what was expressed in each photograph was determined by a photographer’s ideals and the social class and community s/he belonged to. Individual photographers gained commendations and pleasure by making those changes. It would also be rewarding to achieve such technical accomplishments. You can almost sense each photographer’s pleasure. I can’t believe that one would undertake such tasks in pain, agonizing over whether it amounts to faking, which should attract moral condemnation. It must have been be satisfying for the photographers to apply their skills for manipulation: “You can’t tell, can you?” “Zhang wouldn’t be able to do it, would he?” “Only I could do it so well, no?” Very gratifying.

Gao: According to the photographers’ own words at the time, their primary ideal was to represent reality truthfully.[4] They didn’t approach the issue in a philosophical way—for example, that the two-dimensional representation of the three-dimensional world isn’t really truthful. They just wanted their creation to be as close to real life as possible. Their second ideal was that their photographs would provide people with an incentive—a drive to push things in a better direction and develop a better work attitude. That was their lofty ideal.

Fu: To be honest, I believe in their second ideal, that is, that the elevating function of photography was stronger than the ideal of truthful representation. Moreover, their truthful representation of reality was often made after an idealized reality. Therefore, their photographs couldn’t help but avoid some aspects while amplifying others.

For example, in the minds of photographers, war heroes would gradually grow taller. The next time the photographers met a hero, they were often surprised. “Were you always this short? I remember you were really tall when I interviewed you.” The hero might reply, “I couldn’t be that tall; otherwise, I wouldn’t have been able to get into the tank.” In fact, the heroes didn’t grow shorter with aging; they weren’t tall in their youth.

That’s precisely an idealized reality. The truthful representation of reality in photography during the Mao era is a “reality” of this nature.

Gao: When Henri Cartier-Bresson [1908–2004] visited China, in 1957, he went to make photographs at the Miyun Reservoir along with his Chinese peers. The Chinese photographers’ first impression was that Bresson shot a lot and wasted a lot of film. Their second impression was that Bresson captured odd moments instead of typical scenes of people working at the reservoir.

Fu: Bresson captured what he saw as an individual photographer; the Chinese photographers at the time captured what their profession required them to see. Actually, Chinese photographers used to take photos for themselves. Sha Fei, for instance, took photographs that were considered standard and politically correct but might seem fake today, but he took photos through an individualist lens as well—for example, his injured foot, or group portraits of visiting friends. One of the contributions made by Bresson, as a photographer interested in the nature of photography, was to offer examples of individualized views.

Gao: In the fifties, we began to learn from the Soviet Union and took staged photographs. One example is Yuan Ling (1924–) photographing a Chinese-made automobile at the Changchun No. 1 Automobile Factory in 1956. This group of photos by Yuan received harsh criticism: First, except for the shell of the car, none of the parts were made in China. Of course, we might say that this is an issue of journalistic authenticity instead of an issue of photography. Second, in order to get an aesthetically compelling photograph, Yuan Ling staged high-spirited and well-dressed workers at proper positions to create a nice-looking composition. Third, he wasted much of his comrades’ time as he spent days there waiting for the right light conditions.

Fu: Every nation has its propaganda for nationalism and patriotism. The United States of America is no exception. When Dorothea Lange took her iconic photograph Migrant Mother (1936), she kept arranging and adjusting her subjects. She hid the adolescent girls behind the mother and removed the hand on the fence, and so on. What she wanted in the photograph was an American figure, one whose image already existed in her mind.

The military photographers of the United States are not much different from their Chinese counterparts. Had they seen what Cartier-Bresson did at the battlefields of World War II, they would have felt equally odd.

Right after Henry Fox Talbot invented the calotype process, he created the first photo book, The Pencil of Nature (1844–46). You can tell that he himself was stunned. He recognized that this new method was different from painting. Thus, two questions arose: “What is this new invention?” and “What can this new invention do?” In fact, what we’ve been discussing is what this invention can do instead of what it is. When discussing photography, we need to thoroughly separate these two aspects. But in reality, they can’t be entirely separated.

Without knowing about the FSA [Farm Security Administration] or the crisis in the States at that time, we can still appreciate, or perhaps better appreciate, Lange’s Migrant Mother. Therefore, there is beauty in this photograph that’s purely photographic.

When I was little, my dad asked me whether I knew about the Medici. And I didn’t. But when he asked me whether I liked the sculptures commissioned by the Medici, I said yes. Awhile ago I asked an Italian if he knew of the Medici and he wasn’t sure. Italians know about the Medici from Michelangelo’s sculptures. The sculptures demonstrate the beauty of art, but these sculptures were made to serve the Medici family and to be put in memorial halls and such. In the early days of photography, many people focused simultaneously on the questions regarding “what photography is” and “what photography can do.” More often than not, their interest wasn’t concerned with aesthetics, but it nonetheless contributed to the construction of the discourse of photographic nature for purposes such as making documents and providing evidence.

Gao: Perhaps we can say that the nature of photography is more or less objective, but we have various means—such as masking, merging, collage, and montage—to undermine this objectivity.

Fu: Apart from these methods, the undermining of objectivity can go back to the act of photographing, and even further to the choice of lens and film, and even further to the manufacture of lenses and film . . . All these steps involve a great deal of subjectivity, permanently counterbalancing that little dose of objectivity.

The objectivity of photography is that the subject has to appear in front of the lens to be photographed, with the only exception of photogram photos. As to how the lens frames what’s in front of it, and what kind of lens it is, depends on the subjective decision of manufacturers. Then photographers have their own choices: different lenses yield different results. The choice of film, for example Agfa or Kodak from the same period, also produces different effects. And that’s before we even mention the processes of printing and enlargement. In each case, subjectivity plays a big role.

Different operations produce dramatically different effects. During the process of enlargement, for example, a bright photograph with clearly visible pubic hair may be considered pornographic. But it can easily become a photograph of a different kind if one darkens the pubic area making it look more natural. Just by increasing or reducing the exposure for a few seconds the shadows can be black without details or clear and bright—two completely different photographs. So when we talk about authenticity, we need a boundary so we can calmly face what is not authentic. Photography is no more authentic than is painting or memory.

I don’t know whether anyone else talks about truthfulness in this way. Even Robert Capa, whom we regard as the forerunner of truthfulness, never discussed truthfulness. He talked only about “good” photos. He claims that if your photographs aren’t good enough, it’s because you aren’t close enough to the battlefield. To him, making a “good” photograph is the priority for photographers.

GAO Chu is a scholar and curator of Chinese photography. He has spent more than ten years to build an alternative archive of Chinese photographers, collecting oral history and negatives, photos, and diaries of photographers active between the 1930s to the 1980s. He has published widely on Chinese photography. He now serves as the Director of Social Archive of Chinese Photography (SACP) at the School of Intermedia Art, China Academy of Art.

FU Yu is a photographer based in Beijing. He graduated from Lu Xun Art Academy. His solo exhibition, initially launched at the Central Art Academy Museum in Beijing, travelled to multiple cities and won him critical acclaim. Fu was named the “most influential photographer of the year” in 2012 by Award of Art China (AAC). He has published Ping’an siji (Peace of four seasons), Yinyan xizuo (Works in Daguerreotype,) and Xuanlan (Splendor).

WANG Shuo, an independent scholar of Chinese classical literature, is also interested in Chinese photography. She is a core member of a private archive institution about Chinese photography based in Beijing. She has participated in the project of collecting, sorting, and exploring the photos taken in rural northern China; and serves as co‐curator of the exhibition “North Rural China: 1947–1948.” Her three-volume book (in collaboration with Gao Chu) "David Crook and Isabel Crook's photos and interviews about Ten Mile Inn" is to be published soon.

Note: We would like to thank Yuan Ling, Jin Yongquan, and the families of Wu Yinxian, Gao Fan, and Zhuang Xueben for their continuous discussion with us on Chinese photography and for their generous permission to publish the images accompanying this interview.

Notes

Luo Guangda. Xinwen sheying changshi. Jireliao junqu zhengzhibu, 1945; Shi Shaohua. Sheying lilun he shijian. Beijing: Xinhua chubanshe, 1982.

For example, see Shi Shaohua’s closing remarks at the Third Conference on Photojournalism, at the Xinhua News Agency in 1956, in Shi, Sheying lilun, 53–61.

Zhuang Xueben. Zhuang Xueben quanji. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2009.

Guanyu xinwen sheying zhenshixing wenti taolun de zongjiexing yijian. Beijing: Xinhuashe, 1959.