Manipulation as Art: Photographs by Xu Zhuo, 1979–1981

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Introduction

In 1979, some young enthusiasts in Beijing formed one of China’s earliest non-state photography groups, the April Photo Society (Siyue Yinghui, 四月影会). The group organized three annual exhibitions (1979–81), each presented under the title “Nature, Society, and Man” (Ziran Shehui Ren, 自然·社会·人). Taking place at the onset of a relatively relaxed era, after the removal of some of the strictures of the Cultural Revolution, each exhibition showed humanistic images of quotidian beauty that appeared new, breaking away from the dominant genre of propagandistic photojournalism (xinwen sheying, 新闻摄影).

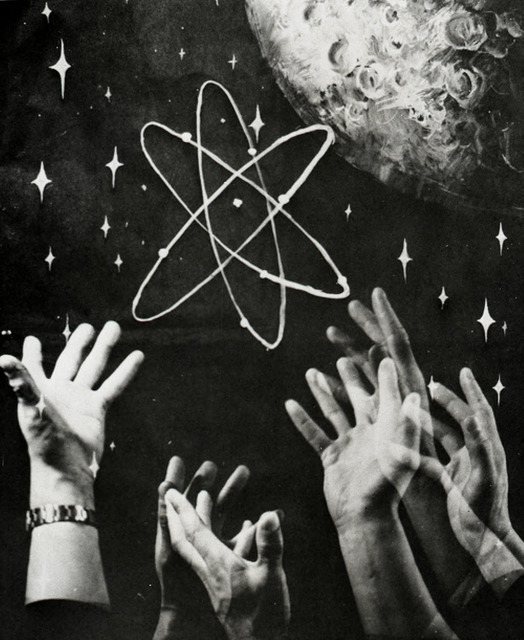

Xu Zhuo (许涿, b.1947), then a collections photographer at the National Art Museum of China, was one of the April Photo Society’s key members. He had studied art at the middle school affiliated with the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing (1963–67), and unlike other photographers who aimed their lenses at everyday life, Xu searched for alternative approaches. He practiced photography as an art form using image manipulation such as long or multiple exposures, as well as darkroom effects and studio props connecting art and photography. [Fig. 1]

If realistic documents of everyday life were new and refreshing subjects for the public, Xu’s experimental images were rare and challenged the dominant, officially sanctioned visual culture, in which such formalism was still taboo. Although art photography (yishu sheying, 艺术摄影) as a genre was recognized and discussed at China’s inaugural Annual Photography Theory Conference, in 1980,[1] formal experimentation was often seen as a “modernist” practice and widely criticized along with the Western philosophy, art, and culture that had begun flooding into China upon the 1978 announcement of economic reforms. Xu Zhuo was at the forefront of photographic experimentation at the time but had to walk a tightrope to balance his hopes for increased openness and pluralism with the reality of confusion and control.

In the following interview, conducted at Xu Zhou’s Beijing home in late October 2014, Xu discusses image manipulation as an important technique for creating artistic photography and reveals how some of his best-known photographs were produced. Note: This interview was carried out during fieldwork supported by The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Greater China Curatorial Residency Programme 2014, Asia Art Archive.

Chen: When did you first come in contact with photography?

Xu: My classmates and I were sent to a military farm in Wei County, Zhangjiakou, in 1969. We planted rice as a form of reeducation during the “Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside” movement in the Cultural Revolution. After three years working on the farm, I returned to the city, in 1972, and waited for the allocation of a job. I had quite a bit of spare time, so I used to hang out with a classmate whose family owned a camera and an enlarger. Most of the time we took photographs of ourselves. We never thought about taking photographs creatively.

We were very poor; all we could afford were cheap chemicals and the off-cuts of photographic paper sold by the jin (half kilogram). We learned how to develop film and print photos just as something to pass the time. In my classmate’s makeshift “darkroom,” we developed film in a kitchen bowl filled with chemicals. That was a lot of fun. In 1973, I was eventually assigned to work for the photography team at the National Art Museum of China.

Chen: At the National Art Museum of China, what did your photography work mainly consist of?

Xu: I was required to create archival records of exhibitions at the museum; my job was to photograph each exhibited work, usually paintings. I would develop the films and then print them for the archives; sometimes I would send images to newspapers for publicity, if requested. In the late 1970s, we mainly used black-and-white film; color film was rare. I spent a lot of time in the darkroom processing film and printing photographs. The darkroom also doubled as a studio. It had good studio equipment, such as lights.

After a few years, I felt bored and wanted to experiment with darkroom manipulation. Actually, this was mostly for the April Photo Society exhibition. Wang Zhiping, one of the main founders of the society, knew me through my classmates and asked me to submit some works for the exhibition. At that time I neither understood nor was interested in realistic or documentary photography. In terms of photographic genres, there was either photojournalism or art photography, nothing in between. Fine art was denounced during the Cultural Revolution but it was gradually revived, and works of landscape, scenery, or portraiture were acceptable.

Although some of the April Photo Society members started photographing street life, I didn’t think that was art photography. The important thing about art photography was to use breakthrough techniques. So I used the facilities at the museum to experiment with photographic manipulation.

Chen: What were the photography facilities at the National Art Museum like at that time?

Xu: They were very good. When I joined the National Art Museum, it was still under the management of the State Council Cultural Group.[2] To better document exhibitions at the museum, the government imported photographic equipment and quite a few good cameras, including German Linhof and Rolleiflex 120 cameras, then later Mamiya 120 and Nikon 135 cameras from Japan.

Chen: Were there any photographic exhibitions at the National Art Museum in the late 1970s?

Xu: Photographic exhibitions hadn’t yet been resumed. I don’t remember when the National Photographic Exhibition started.[3] When people thought of photography, they generally thought of photojournalistic work (xinwen nayitao, 新闻那一套). Therefore, many people didn’t understand the aesthetic of works shown in the first April Photo Society exhibit, in 1979. Some thought they were too romantic, expressing the interests of the petty bourgeoisie and not of the proletariat. Some works were questioned.[4]

Chen: So you had started experimenting in the darkroom when you were asked to show your work at the 1979 April Photo Society exhibition, “Nature, Society, and Man”?

Xu: Yes. Some members of the society were journalists, so when they were on assignment they could take photographs outdoors, such as landscapes and changes seen in the streets. I could work only in the darkroom and studio. Due to my art background and the fact that I was surrounded by painters, I liked works that look like paintings (huayi, 画意), using photographic techniques instead of a brush to create an image. I would start with a certain theme or idea and think of a composition. Then I would photograph the setup of this composition to visualize my idea. I’ll take my work titled Modern (1979; figure 2), shown in the first “Nature, Society and Man” exhibition, as an example.

The Cultural Revolution had come to an end and we were under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, who in 1978 announced the strategy of realizing the Four Modernizations, in the fields of agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology, to reinvigorate China’s economy. What I was expressing was the eagerness of the people for modernization in science and technology. It was a bit like a poster, and still related to politics. This photo attracted quite a bit of attention in the exhibition. Most of the photos were about parks, snow scenes, flowers, and trees; people felt my photo was fresh.

Chen: How did you produce this photo?

Xu: I used gouache to paint a quarter moon on black cardboard. The crater indicated it was the moon. On the same cardboard, I also drew stars and the atomic symbol; I deliberately left the bottom half of the cardboard blank. Then I asked a colleague to squat under the cardboard, with his hands held up to the blank part of the drawing. Using the multiple-exposure technique, I released the shutter three times with my colleague’s hands moving to three different positions in front of the fixed drawing.

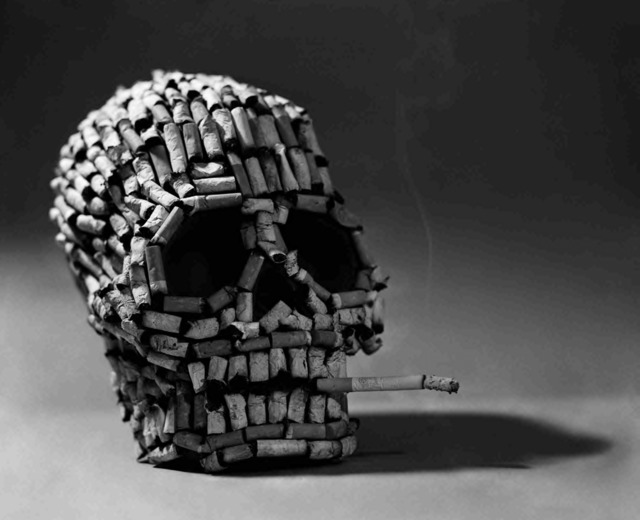

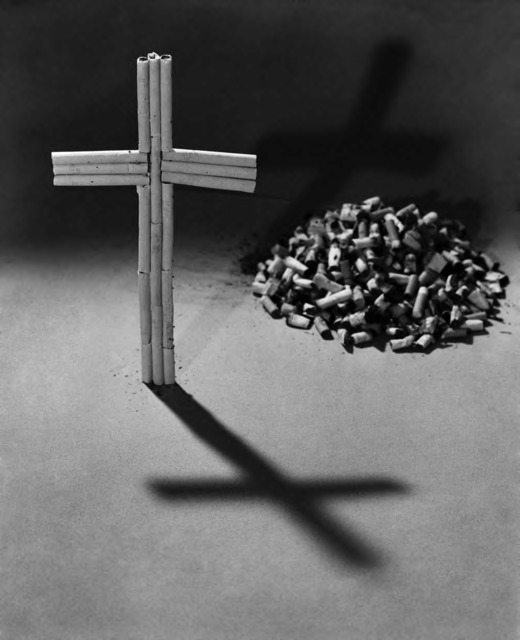

Chen: In the second “Nature, Society, and Man” exhibition, you showed a series of works concerning smoking. Why? Was there an antismoking movement in society, or a government campaign to that effect? [Fig. 3]

Xu: It was publicizing antismoking purely for artistic creation. One of my colleagues had studied sculpture. I asked him to make me a clay skull. I collected cigarette butts from offices in the museum and glued them onto the skull. For the second piece of the series, SOS—Help, [Fig. 4] I put many cigarette butts on a big piece of cardboard with two holes in it. My colleague hid under the cardboard, holding it up with both hands poking through the cardboard, as if trying to get out of a tomb. In the third piece, Graveyard, [Fig. 5] I pinned the cigarettes into the shape of a cross and fixed it on the table. With lighting from the side, the cross threw a shadow that stretched across the image, creating a frightening mood.

Chen: Had you seen photographs by Philippe Halsman, in particular one showing a skull made up of naked female bodies? As far as I know, Halsman’s works were introduced to China in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Xu: No. I hadn’t seen them at that time.

Chen: So it was purely because smoking was associated with death, hence you used the skull to reflect that relationship?

Xu: Exactly. Smoking is harmful. How should I show that association in an image? You couldn’t simply tell people not to smoke. The tomb symbolized death; two hands reaching out showed that the person was drowning from the pile of cigarette butts; the smoking skull made of cigarette butts symbolized the death that would result from smoking.

Chen: This series showed some characteristics of advertising for public interest. Did this type of advertising or even this type of consciousness exist in the 1970s and early 1980s?

Xu: Not really.

Chen: So you wanted only to make a piece of art?

Xu: Yes. I just wanted to take part in the exhibition, so I produced some artworks for it. I didn’t think of the publicity function of the works. I smoked a lot at that time; I was smoking when I made those works! My friends criticized me about that. I told them I just couldn’t quit.[5]

Chen: Were there any criteria for works to be shown in the April Photo Society exhibition?

Xu: There wasn’t much of a clear theme or any criteria for any of the three exhibitions organized by the April Photo Society between 1979 and 1981, but there was still a kind of self-censorship. Your work couldn’t be too vulgar or too reactionary. It couldn’t be so political that it might offend officials, and of course you couldn’t show anything pornographic. We all understood this, so we focused mainly on pure art (chun yishu, 纯艺术), although later exhibitions showed works that commented on social issues.

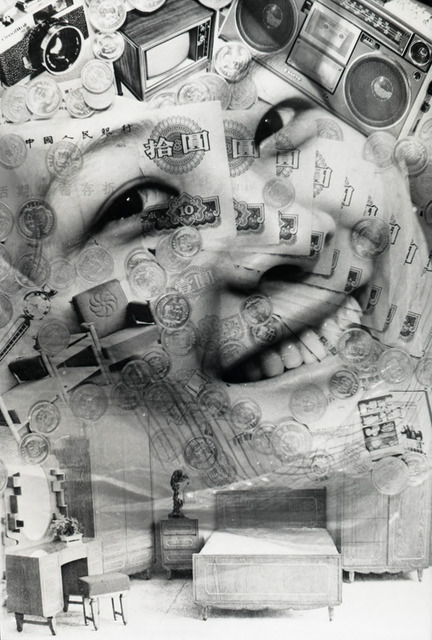

Chen: Did your work I Love You (1980) [Fig. 6] expose some kind of social phenomenon from the time?

Xu: Indeed. I always wanted to make photography with a particular theme and content. The concept of I Love You was to criticize the fact that young girls loved rich men and desired luxurious wedding presents. The radio, camera, TV set, and furniture were luxury goods at that time. In the photo they were all cut out from advertisements in pictorial magazines.

I put these cut-out items together with some ten-yuan notes—the highest denomination in Chinese currency at the time. To make the image flow better, I used coins to cover the cut edges of these items and rephotographed it. When I placed all these things on the paper, I deliberately left the middle blank—a space for the face of the girl. Photographing the girl was easy; that was taken in the darkroom-cum-studio against a white wall. To emphasize the face of the girl, I blurred other parts of her head when I enlarged the negative. Both of these photographs were taken with a soft-focus lens to give a better effect when I combined the two negatives.

Chen: Besides experiments using props to set up the photographic scene or combining negatives to express particular concepts, you also explored the use of multiple exposures.

Xu: Right. The Indian Goddess series (1980; figures 7, 8, and 9) was photographed by moving the camera and making multiple exposures, although one image was made by projecting images onto a plaster cast (see figure 7). The Flower series (1980; figures 10 and 11) was also photographed with multiple exposures.

I lived in a little house behind the National Art Museum. One night I took a gas burner to the courtyard and lit a very small fire to produce just enough light for photography. To get different-size “flowers,” I moved the camera back and forth, higher or lower, to create different shapes. With each move I would make one exposure. I also deliberately left the bottom part of the negative blank for the vase, which I photographed later in the darkroom, after I had finished working with the gas burner. These were made into one negative. Again, all these required planning and a concept beforehand.

Chen: Were these simply experiments or did you produce this series for an exhibition as well?

Xu: It was for an exhibition on darkroom techniques organized by the Beijing Photographers Association. It was held in late 1980 in Zhongshan Park, a few months before the second “Nature, Society, and Man” exhibition. They invited me to participate.

The other photograph of the Flower series was even easier to produce. I used the long-exposure technique. Wrapping the bulb of a torch with different-colored cellophane, I traced circles and lines in front of a black velvet cloth on the wall while depressing the shutter.

Chen: The word photography means “light drawing” in Greek. This work expresses that meaning.

Xu: I think drawing and photography are interlinked. Some people use brushes and others use a camera to express ideas and compositions. I think photography is a very good method.

Chen: What made you interested in the multiple-exposure technique in the late 1970s and early 1980s?

Xu: The National Art Museum subscribed to some overseas art and photography journals and magazines, such as Photo Pictorial from Hong Kong and the Lion Art Monthly from Taiwan. I didn’t appreciate the salon photography featured in Photo Pictorial; as I said, I was more interested in techniques and photographic concepts. There was a German photography magazine that I liked a lot, but I don’t recall its name. It featured many works with multiple exposures—for example, a person appearing in different places in a single image. I found that very interesting and wanted to imitate it.

Chen: How about your image featuring many lightbulbs and some chicks? [Fig. 12] It doesn’t seem to involve much darkroom technique or photographic manipulation; it’s more like an industrial art photograph or, to be more specific, a creative advertising image.

Xu: The broken bulb next to the chicks made one imagine they had hatched out of eggs. The bulbs and the chicks had no connection at all, but with deliberate arrangement in the image they became related. It looks a bit like a contemporary artwork, but this photo is still far from contemporary art. It was only a thought, an idea that was demonstrated by photography. It wasn’t very profound. It was a kind of photographic experiment that not many people were doing at the time.

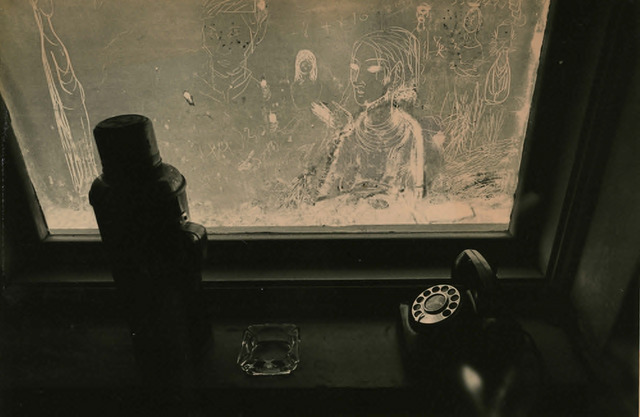

Chen: Besides these works, your photograph A Corridor at Painting Institute (c. 1980; figure 13) was very different. It uses no special techniques or arrangement of props.

Xu: It was taken in a corridor of the Research Institute of Chinese Painting. The drawing on the glass was made by artists with knives; in the foreground a telephone, thermos, and an ashtray on the windowsill formed a still-life composition. I found it interesting, so I took a photograph of it.

Chen: Did you take many of these kind of snapshots?

Xu: Not many. It would be great if I had taken more photographs like this. I regret now that I didn’t take many realistic-style photographs. I didn’t value this kind of photography then, but instead wanted to make photographs with complicated techniques and manipulations. I should have taken more documentary-style photographs.

Chen: Were there many places to publish photographs back then? Apart from invitations to exhibit, did you try other avenues to publish your works?

Xu: We did want to show our photographs to others. There weren’t many newspapers or magazines, so there were few opportunities to publish. Nonofficial exhibitions played an important role in developing photography at that time. The April Photo Society exhibitions attracted so many people; that was sensational. It was a valuable opportunity to be exhibited in public, particularly for young amateur photographers. I didn’t think much about that because I was a professional photographer and worked in an art museum. I didn’t seek out venues to publish my work.

Chen Shuxia is a PhD candidate at the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University, researching photography groups active in China in the 1980s, and the grantee of the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Greater China Curatorial Residency Programme 2014, Asia Art Archive.

Notes

“Speech Excerpts from the 1980 National Photography Theory Annual Conference一九八零年摄影理论年会部分发言摘录,” Chinese Photography中国摄影92 (1981): 4–5.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Ministry of Culture was abolished and all cultural affairs were managed by the State Council Cultural Group (Guowuyuan wenhuazu, 国务院文化组), formed in 1970. The group chief was Wu De (吴德), but its operation was overseen by Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong’s wife and a core member of what came to be known as the “Gang of Four.”

The first National Photographic Exhibition was held in 1957 and stopped in 1966 due to the Cultural Revolution; it restarted in 1973 and continued until 1977; it then finally resumed in 1982 at the National Art Museum.

Works such as Wang Miao’s (王苗) Inside and Outside the Cage (Longli longwai, 笼里笼外) and Peony Tombs (Shaoyao zhong, 芍药冢) and Wang Zhiping’s (王志平) Family (Jiating, 家庭) were questioned. These works were mainly criticized for their content being sentimental, vulgar, and longing for freedom, which was bourgeois. Formal experimentation was also criticized because the audience wouldn’t understand what those lines and colors were for. These criticisms came mainly from the Photography Department of the Xinhua News Agency. Zhong Juzhi (钟巨治), “Adhere to the Socialist Direction of Photographic Art必须坚持摄影艺术的社会主义方向,” The Eternal April 永远的四月 (Hong Kong: China Book Company, 1999), 102–108.