Exhibition Review: Chinese Contemporary Photography 2009-2014, Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chinese Contemporary Photography 2009-2014 (zhongguo dangdai shying 中国当代摄影 2009-2014), exhibited from September 1 to October 15, 2014, at the Minsheng Art Museum was a highlight event of the inaugural Photo Shanghai, the first art fair dedicated exclusively to photography in China. Billed as a major milestone in Chinese photography, the exhibition featured 52 artists or collectives and was jointly organized by the Minsheng Art Museum in Shanghai and the Art Museum of the Central Academy of Fine Art (CAFA) in Beijing. The artists featured are staples of recent photography exhibitions in China, pulled from the networks of the curatorial team led by CAFA Art Museum director Wang Huangsheng 王璜生 and including major figures in the field, such as the Fudan University professor Gu Zheng 顾铮, CAFA Art Museum curator Tsai Meng 蔡萌, Three Shadows Photography Art Centre director RongRong 荣荣, independent curator and editor Li Mei 李媚, and Deputy Director of the Minsheng Art Museum, Weng Yunpeng 翁云鹏.

This exhibition is an abridged version of Chinese Contemporary Photography Since 2009, a large-scale exhibition curated by the same team a year before in conjunction with Aura & Post Aura: The First Beijing Photo Biennal (lingguang yu hou lingguang: shoujie Beijing guoji sheying shuangnian zhan, 灵光与后灵光:首届北京国际摄影双年展).

Both exhibitions aimed to present an overview of photography in China in the years immediately following the Beijing Olympics in 2008. As the curators note, this period was particularly important to China since the country’s relative stability during the global financial crisis pointed toward a new world order. A sense of cautious national pride serves as the backdrop for the exhibit. In the foreword to the accompanying exhibition catalogue, Ai Min, director of the Minsheng Art Museum, writes, “This exhibition, by nature, is a narrative about ourselves rather than a presentation of ‘others.’”

When teaching, I often use the analogy of a carefully crafted essay to talk about exhibitions. In this review, I’ll take Chinese Contemporary Photography 2009-2014 as a state-of-the-field event in order to think about some of the questions posed by the curators. Wang Huangsheng writes that the exhibition developed out of concerns about photography’s role in society, specifically how photography could intervene, and what it could record and express in light of China’s increased “hard power” and concomitant emphasis on “soft power.” Given photography’s history in China and current trends in the field, what new questions could the medium put forward?

The exhibition is divided into three loose units: “boundary / drift,” “landscape / quotidian,” and “society / body.” Although the curators stress the units are not static categories (and the English translations of the titles are not consistent), they do provide a useful organizational structure for understanding the work.

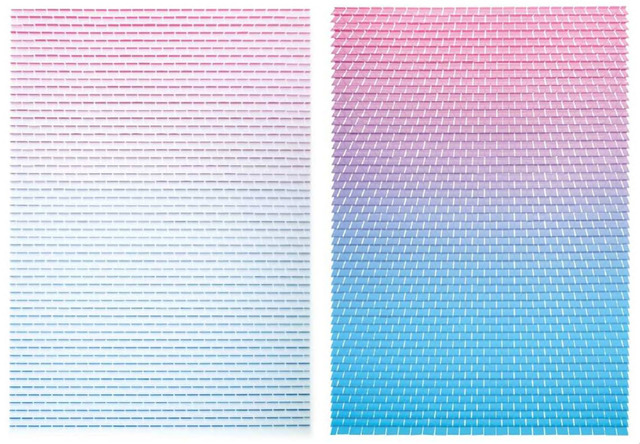

In “boundary / drift,” the curators address experiments with the formal boundaries of photography as a medium. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, pictorialism and modernism were the last Western traditions of photography to become popular in China before the Communist victory in 1949. From then on, until the ”reform and opening up (gaige kaifang 改革开放)” in the late 1970s, Chinese photographers had little exposure to resources about photography. Thus, there has been a recent reactionary phenomenon of photographers who feel the need to catch up and explore traditional, analog techniques. Photographers like Luo Dan 骆丹 (b. 1968) value the element of unpredictability inherent in wet plate photography, while Qiu 丘 (b. 1974) has maintained the craft of a darkroom practice since the 1980s. Painterly experiments with calligraphy and ink painting, as seen in the work of Wei Bi 魏壁 (b. 1969) and Shao Wenhuan 邵文欢 (b. 1971), have also developed as artists test the boundaries of traditional art forms in relationship to photography. Conversely, artists like Wang Ningde 王宁德 (b. 1972), Jiang Pengyi 蒋鹏奕 (b. 1977), and Sun Lue 孙略 (b. 1976) play with the very definition of photography as “drawing with light” (from the Greek photos and graphé). Wang Ningde’s striking “Form of Light,” for example, asks us to consider the illusory nature of photography, with images constructed out of hundreds of color negatives that stand perpendicularly to the canvas, casting shadows on its surface.

Luo Dan, Simple Song 001, Gathering on Thanksgiving, Wawa Villlage, Wood, Paper, Aluminum plate, Acrylic, 29.7×21cm, 2010.

Luo Dan, Simple Song 001, Gathering on Thanksgiving, Wawa Villlage, Wood, Paper, Aluminum plate, Acrylic, 29.7×21cm, 2010.  Wang Ningde, Color Filters for the Utopian Sky No.1, Aluminum Plate, Acrylic, Aluminum Sheet, 146cmx6cm, 2003.

Wang Ningde, Color Filters for the Utopian Sky No.1, Aluminum Plate, Acrylic, Aluminum Sheet, 146cmx6cm, 2003. Works in the “landscape / quotidian” section deal with the familiar themes of urbanization and development, topics that cannot be ignored in fast-changing China. Recently, Zhang Kechun 张克纯 (b. 1980) and Zhang Xiao 张晓 (b. 1981) both gained international attention for their surreal photographs of scenes alongside bodies of water (the Yellow River and the country’s coastline, respectively). Wang Guofeng 王国锋 (b. 1967) takes the concept of landscape to the level of spectacle in his panorama of the mass celebration of North Korean founder Kim Il Sung’s birthday. By digitally enhancing the image, he zeroes in, step by step, on the face of a female soldier overcome with emotion – a small, yet still human pixel. Landscapes can also be found in the everyday, ordinary aspects of life, as in Feng Yan’s 封岩 (b. 1963) portrait series of obsolete furniture or Li Jun’s 李俊 (1977) images of absent things revealed only through their traces in dust and paint. Zhu Lanqing’s 朱嵐清 (b. 1991) intriguing handmade photobook, which traces her return to her coastal hometown in Fujian province, perhaps best connects the themes of landscape, quotidian, and memory in this section.

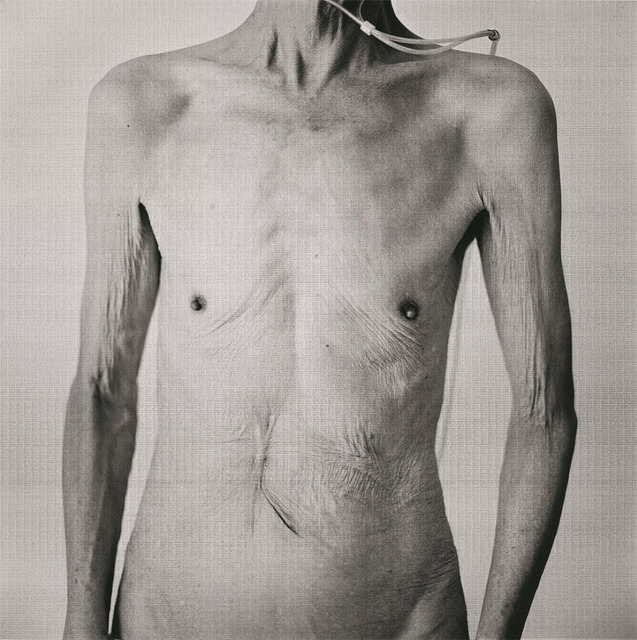

The last section, “society / body,” focuses on the relationship between the individual and the collective. In journalism, the notion of the collective good drives documentary photographers like Lu Guang 卢广 (b. 1961) and Taiwan’s Yao Jui-Chung 姚瑞中 (b. 1969) to expose social and political ills in order to evoke public action. The “Lost Society Document” (LSD) is an art collective that grew out of a workshop that Yao taught, which trained students to survey, document, and photograph “mosquito houses,” or abandoned, publicly-funded buildings. The resulting publication forced the Taiwanese government to recognize the “mosquito houses” and set up an investigation into the issue. While Yao employs photography in a classic documentary mode, the duo of Li Yu 李郁 (b. 1973) and Liu Bo 刘波 (b. 1977) is more mischievous, reenacting headlines pulled from the front page of newspapers to give the stories a new sense of life. Taking inspiration from journalism, they re-present reality rather than attempt to capture it. In the same vein, some artists today are more interested in conveying their individual, subjective perspectives, such as the sex-infused work of Ren Hang 任航 (b. 1987) or Li Lang’s 黎朗 (b. 1969) intensely personal portraits of his deceased father.

Li Yu and Liu Bo, Civilized Administrative Enforcement Caught a Citizen Who didn't Want to Move Home, Inkjet Print, 2006-2010.

Li Yu and Liu Bo, Civilized Administrative Enforcement Caught a Citizen Who didn't Want to Move Home, Inkjet Print, 2006-2010.  Li Lang, A Father 19271203-20100827 Body A, Inkjet Print, with Pencil Writing 107.8×106.6cm, 2012-2013.

Li Lang, A Father 19271203-20100827 Body A, Inkjet Print, with Pencil Writing 107.8×106.6cm, 2012-2013. Each of these units can no doubt stand as exhibitions on their own. The juxtapositions are large enough and rich enough to encompass multiple artistic strategies without being jarring. While I would like to have seen more coherent, edited sections and contextual support in the form of wall texts, the exhibition did demonstrate the diversity of interests in Chinese contemporary photography today. Underlying the curation of the show, however, is a certain anxiety about the future of the medium in China, which is manifested as a tendency to retell stories of historical firsts – for example, the first collection of photography in a museum (Guangdong Museum of Art, 2003), the first photography art centre (Three Shadows, 2007), the first photography biennale in Beijing (Aura & Post Aura, 2013), etc. In focusing on “narratives about ourselves,” the curators strive to secure the place of photography in Chinese institutions.

This institutional drive is compounded by a deeper, related anxiety about photography’s relationship with the world in the digital age. In the catalog essays for both this and the Aura & Post Aura exhibit, Gu Zheng compares the impact of digital photography and social media in the last decade to photography and film’s dimming effect on “aura” in the early twentieth century. “Aura,” according to Gu, is an enchanting “breath of life” intrinsic to handcrafted, traditional art that is nearly lost with the rise of mechanical production. The ease of digital photography in recent years has further increased the speed of image production and reproduction, distancing us from “aura” and causing our understanding of the world to become more superficial, hence the concept of the “post-auratic” age. Yet, one can argue that this notion of “aura” is an effect of reproduction itself, a yearning for authenticity or originality that only exists retrospectively. Works of art, including photography, are masses of relations, citations, and references, which cannot be reduced to a single understanding. No works are created in a vacuum, and any “narratives about ourselves” necessarily imply others. So, in this context, rather than ask how digital photography can reveal the world, perhaps the better question is: how can photography–whether digital or not–help us navigate through all that we have inherited?

The exhibition was accompanied by a catalog: Chinese Contemporary Photography 2009-2014 (Shanghai: Zhejiang Photography Publishing House, 2014), edited by Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum and Central Academy of Fine Art. Photographs in this review provided courtesy of the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum.

Stephanie H. Tung is a Ph.D. Candidate in Chinese art history at Princeton University. Prior to her studies, she worked as a translator and curator for the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing, where she co-authored publications including WATW, We are the World: Photography from China and the Netherlands (2010) and Ai Weiwei: New York 1983-1993 (2010). Most recently, she contributed to the forthcoming Aperture publication, The Chinese Photobook (2015).