Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad: Fields of Sight

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

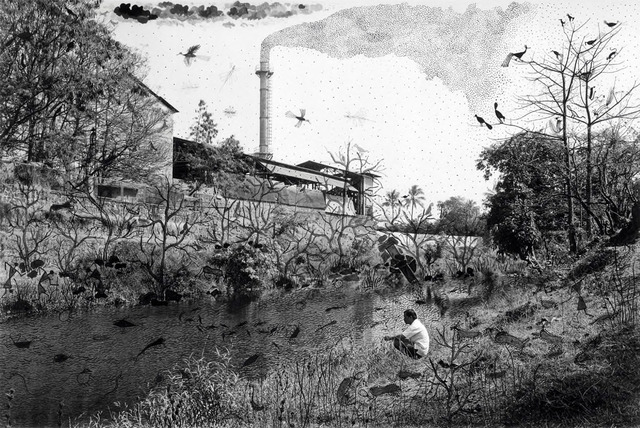

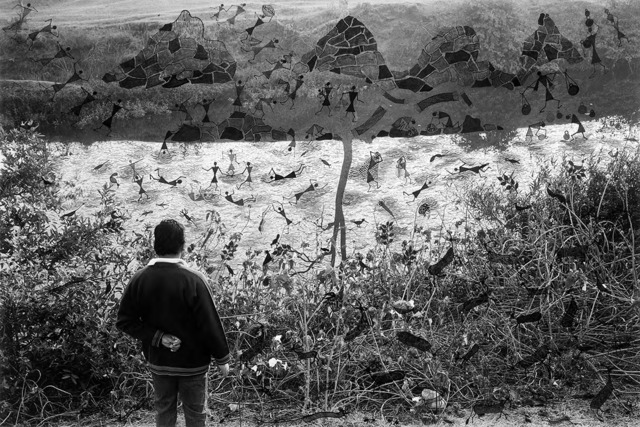

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Factory and River, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Factory and River, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. Once in a while an artistic practice emerges that challenges viewers in new ways that cut through the noise, and offers something both deeply familiar and at the same time utterly new. Collaborative, creative, and experimental, Gill and Vangad, in Fields of Sight, provide a new language for art practices that address the politics and aesthetics of environmental destruction. Ecocriticism comes alive through the conjoining of photography and Warli painting, hoping to replace one modern history with another history, one that is contemporary. If the modern is marked by notions of progress, development, and nationalist discourses of decolonization, the contemporary moment, with its rampant inequalities and environmental destruction, calls for a politics outside of the modernizing narratives of the nation-state.

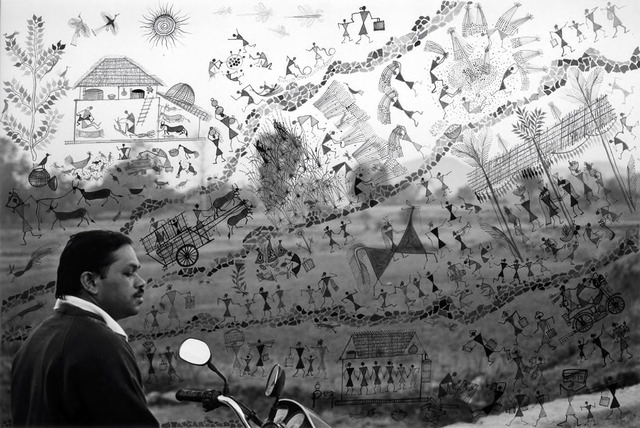

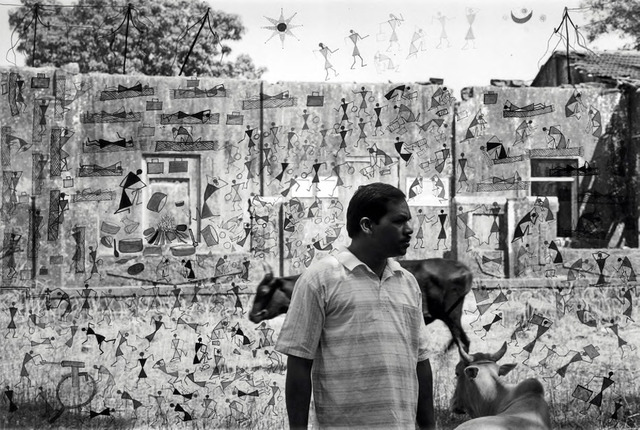

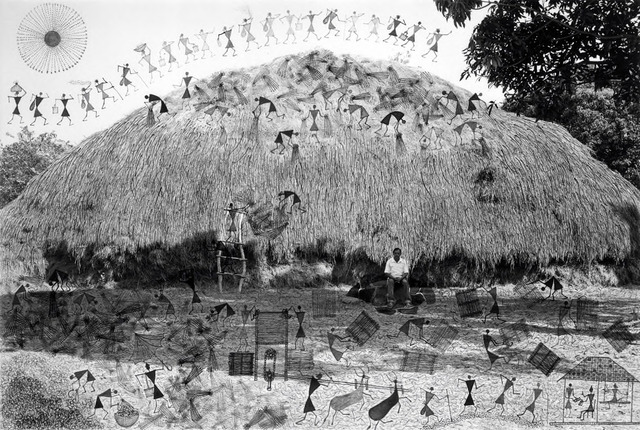

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Memories Come to Rajesh, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Memories Come to Rajesh, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Collecting Herbs in the Forest, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

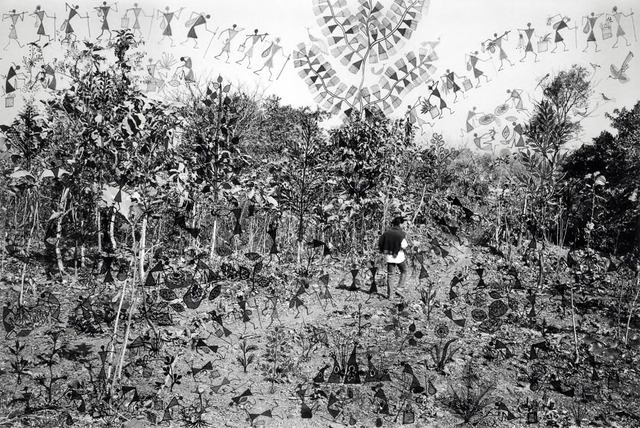

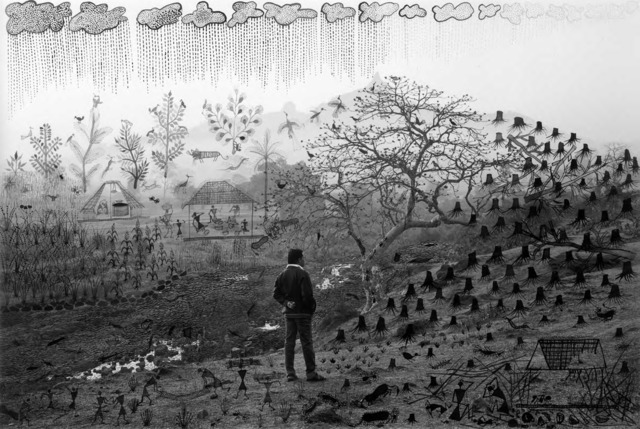

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Collecting Herbs in the Forest, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Destroying the Forest, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

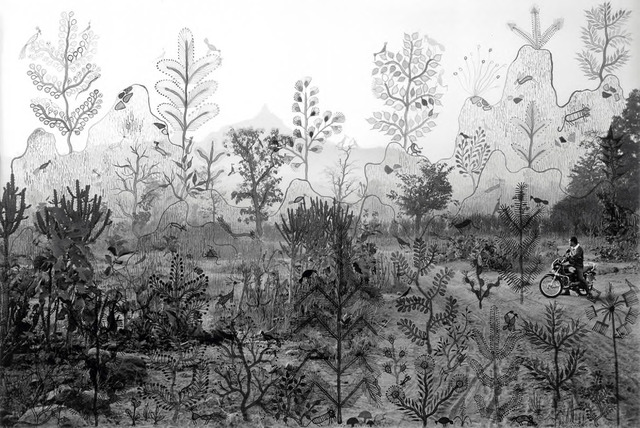

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Destroying the Forest, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. Denuded landscapes, infested and opaque waters filled with sewage and chemical sludge, garbage dumps, abandoned houses and communities have all become the new critical language of environmental photography as political art. The images present us with an aesthetic of the lost landscape, trying to evade the inevitable pleasure of photographic capture or that frisson of pleasure in destruction. Photography’s relation to death and time, in Roland Barthes’s formulation, became allied to this aesthetic language of ecocriticism. Yet so many of these practices inevitably succumbed to the sublimity of empty landscapes of “nature,” or the aesthetic of the picturesque as histories of nostalgia for landscapes that can be controlled (even to look natural). Breaking from this language, Vangad and Gill mix media, languages, stories, modernities in a collaborative project that defeats the reinscription of the history of landscape art and the valorization of an empty construction of “nature” in both painting and photography.

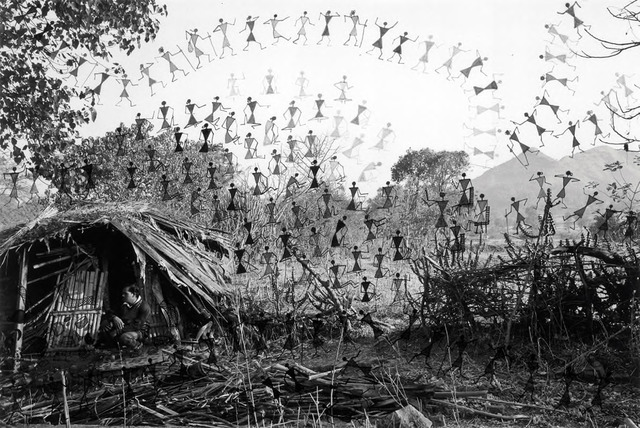

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Mountains and Trees, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Mountains and Trees, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Heaven and Hell, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

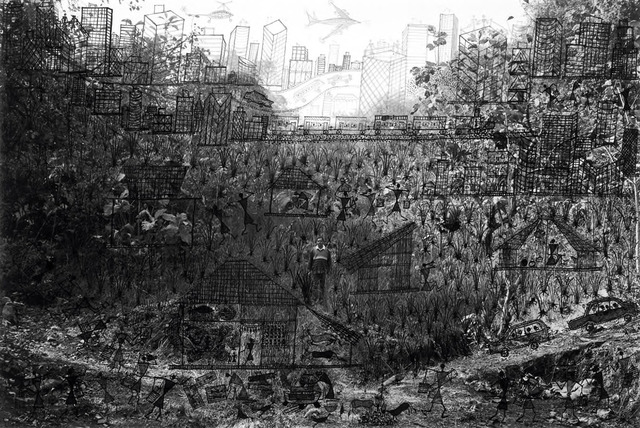

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Heaven and Hell, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. Fields of Sight populates the contemporary photograph with narratives and figures that fill the landscape, reaching up to the sky, visually claiming presence rather than loss. The photographs create landscapes of environmental destruction, and are critical of what is taken as the progress of industrial modernity. But what is lost is not nature or emptiness — as images that claim to participate in ecocriticism often demand the viewer to fill up the emptiness with her own loss. Fields leave us no such space or opportunity. Gill’s landscapes in black and white position Vangad at their center, not simply as collaborating artist/painter but also as narrator, and he takes over to repopulate the so-called lost landscape. Decentering the perspective of power, Vangad’s presence — often with his back turned to the viewer, blocking her ability to see him, replaces that perspective of power with another one, Vangad’s own. He paints fully, much as he might paint walls, houses, and other canvases, but this is not a distant space:, it is his own village and land. Vangad’s painting covers the photograph, populating the landscape with stories of loss, power, ethics, and the politics of land that come from his history, his language, his community.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Village to City, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Village to City, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Orphanage Days, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Orphanage Days, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. Vangad’s prolific and intense figures make demands on the viewer. Warli iconography and landscape photographs merge in a critical language that remakes each medium. We must not remember the lost landscape in terms of pristine worlds, picturesque lands, “natural” worlds empty of people not lost through the coming of other people, but rather through the narratives and worlds of those who have been displaced, seen as non-modern, unfit to be part of the modern state. There were other worlds, Vangad and Gill tell us, other people, other lives and stories.. They are there, not gone, not past. Vangad is in the landscape, not simply of it. The photograph captures him in the place that is his own, but the language of the photograph is not the only one that can speak for him.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Terrors of Hostel Life, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Terrors of Hostel Life, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Great Raid and Battle, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Great Raid and Battle, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. His painting constitutes and inscribes the particularity of place, the history and cosmology of his community. He inhabits and reinhabits, covering all the available space of land and sky of the landscape photograph. There is no demarcation between land and sky, all are filled with his stories, nothing is left to profit and production; the only utility possible is that of his stories. He demands we look at him, through him, at images, narratives, stories, lands, worlds —– his old school, the land altered, the factories spewing black smoke. But looking through him is not simple:, it is demanding, asking us to look closely, decode, decipher, listen, and decolonize. Gill’s photographs become both a setting and a match for Vangad’s intensities.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Hiding in the Seth’s House During the Great Raid, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Hiding in the Seth’s House During the Great Raid, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Village Meeting, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Village Meeting, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. At the same time as Vangad and Gill embed their new form within a historical Indian practice of the painted photograph, they depart from it as well. Refusing to paint over with color the black-and-white photograph, they paint with the same palette but with different intensities, languages, shades, and figures. There are no brilliant colors here. What draws the eye are the somber shades of black and white and the combination (not melding) of divergent styles and languages.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Life by the Water, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Life by the Water, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Fishing, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Fishing, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. Vangad and Gill merge the medium of the black-and-white photograph with the more traditional Warli use of figures and icons in white pigment. The starkness of drawing and painting with shades and textures works not simply to disavow modernity or erase it, but also to remind us of its uses and costs — and not why it must not be an end in itself, but rather, why its limits must be recognized.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Tilling the Land, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Tilling the Land, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Harvest, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Harvest, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. We see here a photographer of and from contemporary, urban India (though of a land-centered community herself) and an artist/painter of the Adivasi community from Maharashtra whose visual narratives work together to tell stories that demand to be heard as equally contemporary, not as relics of a traditional or “tribal” past, a term the British as well as independent India have called Vangad’s communities. He is not a “lost” figure of what Renato Rosaldo called “imperial nostalgia,” asking us to mourn what we ourselves have destroyed. He is not destroyed; he is there, producing a language and art practice that uses the modern medium and its technologies — the photograph, the motorcycle — to assert presence rather than to provide the possibility of mechanical replication of that which is lost.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Moonlight in the Forest, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Moonlight in the Forest, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.  Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Wedding and Tree Worship, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists.

Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, Wedding and Tree Worship, from “Fields of Sight”, 2014, ink on archival pigment print, © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, courtesy the artists. The artistic practice here is one of a demand, a challenge, to recognize rather than to mourn. Vangad and Gill together re-create in a new language the practice of collaboration of the painted photograph. The past is narrative, but narrativizing continues, through mixing the historical and generational practices of Warli painting into the language of the photograph. It is a critical language of demand and recognition, the moment of the photograph now embedded in a plethora of voices, languages, and histories, in the ongoing production of attention, of new ways of seeing.

Gauri Gill is a photographer based in New Delhi. Her work is widely shown and is in the collections of prominent North American and Indian institutions. In 2011 she was awarded the Grange Prize, Canada’s foremost award for photography. Gill’s book Balika Mela was published by Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, in 2012. More information about the scope of her work is available at <gaurigill.com>.

Rajesh Vangad is a Warli painter from Ganjad, Dahanu - an Adivasi village in coastal Maharashtra. He has exhibited his work at Pune, Mumbai, Delhi, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Bhopal in India, and London and Barcelona in Europe and through the Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development Federation of India Limited, as well as the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India.

Inderpal Grewal is Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She is the author of Home and Harem: Nation, Gender, Empire and the Cultures of Travel (Duke University Press, 1996) and Transnational America: Feminisms, Diasporas, Neoliberalisms (Duke University Press, 2005), and (with Caren Kaplan) has written and edited Gender in a Transnational World: Introduction to Women’s Studies (Mc-Graw Hill 2001, 2005) and Scattered Hegemonies: Postmodernity and Transnational: Feminist Practices (University of Minnesota Press, 1994).