Traversing Expanses: The Cambodian-American Diaspora Experience in the Work of Pete Pin, Amy Lee Sanford, and Seoun Som

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Mass international migration of Cambodians in modern history is most commonly cited in connection with civil wars that began in the late 1960s and culminated in the genocidal regime of 1975–79. Among the exiled population, a large number resettled in the United States. The following works, by Amy Lee Sanford, Pete Pin, and Seoun Som, do not attempt to build a unified representation of Cambodian-American communities in the United States; rather, they acknowledge the diversity of diasporic experiences and offer ways to understand their complexity.

Traversing Expanses looks at different kinds of spaces that the artists attempt to investigate and navigate in (re)connecting to their own histories and (re)imagining their worlds of meaning.

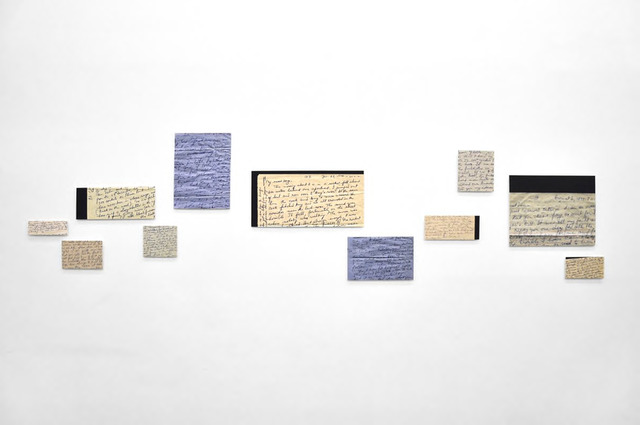

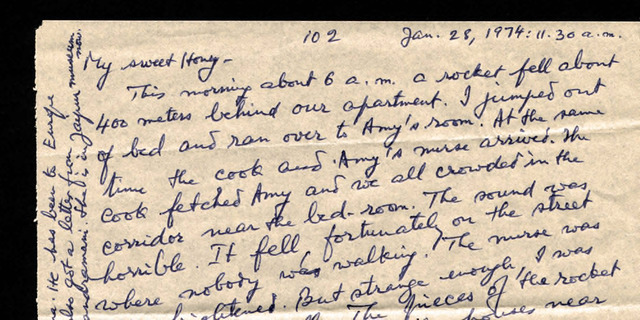

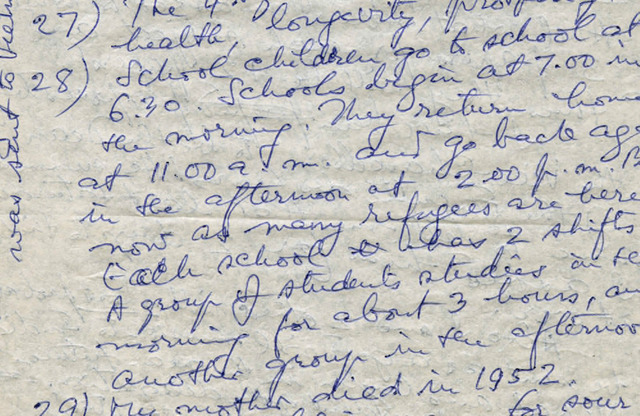

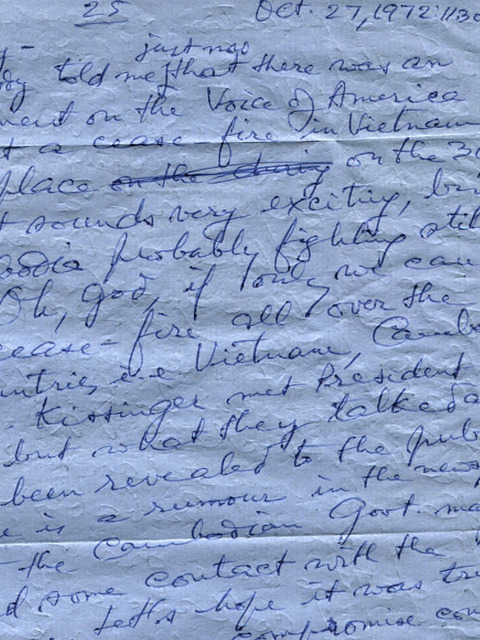

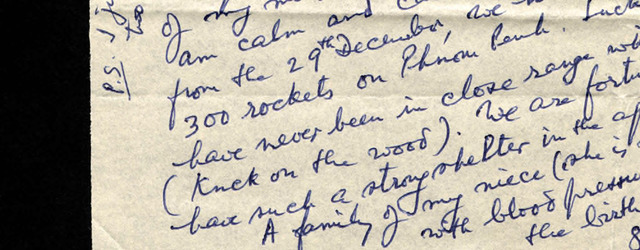

Amy Lee Sanford was born in Cambodia in 1972, during a period of political instability and civil war. When she was two, her father arranged for her to live in the United States. Sanford internally searches for her roots and a sense of belonging by piecing together letters sent from her father before he disappeared, in 1975, shortly after the Khmer Rouge took power. In Fragments (2013), Sanford presents prints of enlarged scanned sections from her father’s handwritten correspondence. These prints can be arranged in a variety of configurations, each with the possibility of its own narrative thread.

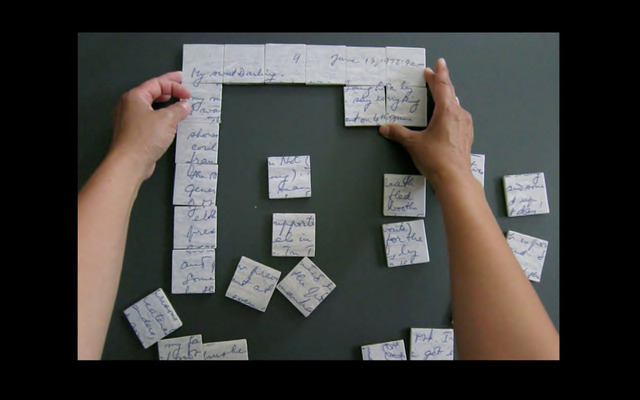

This process of piecing together fragments of memories is intensified in Cascade (36) (2014), a single-channel video that shows the artist’s hands playing with a puzzle of a reproduced letter — a game that finishes in a half-letter piece. Sanford’s resistance to offering a complete narrative challenges our notion of “the” permanent, coherent history. In “On the Concept of History,” the philosopher and theorist Walter Benjamin writes, “Articulating the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was.’ It means appropriating a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.”[1] This radical concept suggests that understanding history is not about trying to put together pieces of memory for a total view, but rather about seizing moments when memory surfaces.

Sanford seems to demonstrate superfluous effort in constructing history. One can sense, however, that this is in many ways the point, as the artist rejects the possibility of giving a complete view of her personal and national history. Instead, she seems to propose histories as a series of an ongoing, active inquiry, one that involves its politics in assembling and reassembling, and that we ought to grasp those “flashing moments” of scattered snippets. Through this process of creatively engineering a personal, meditative space, Sanford also confronts the larger issues of emotional stagnation and reconciliation, and maps the unsettled portrait of herself, her father, and Cambodia.

Amy Lee Sanford, Fragments, 2013, archival pigment print, variable dimensions. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Amy Lee Sanford, Fragments, 2013, archival pigment print, variable dimensions. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Amy Lee Sanford, Jan. 28, 1974, 2013, archival pigment print, 60 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Amy Lee Sanford, Jan. 28, 1974, 2013, archival pigment print, 60 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Amy Lee Sanford, School Children, 2013, archival pigment print, 25.5 x16.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Amy Lee Sanford, School Children, 2013, archival pigment print, 25.5 x16.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Amy Lee Sanford, Oct. 27, 1972, 2013, archival pigment print, 30.5 x 40.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Amy Lee Sanford, Oct. 27, 1972, 2013, archival pigment print, 30.5 x 40.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Amy Lee Sanford, 300 Rockets on Phnom Penh, 2013, archival pigment print, 44 x 17 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Amy Lee Sanford, 300 Rockets on Phnom Penh, 2013, archival pigment print, 44 x 17 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Amy Lee Sanford, video still from Cascade (36), 2014, single-channel, 11 min, 47 s. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

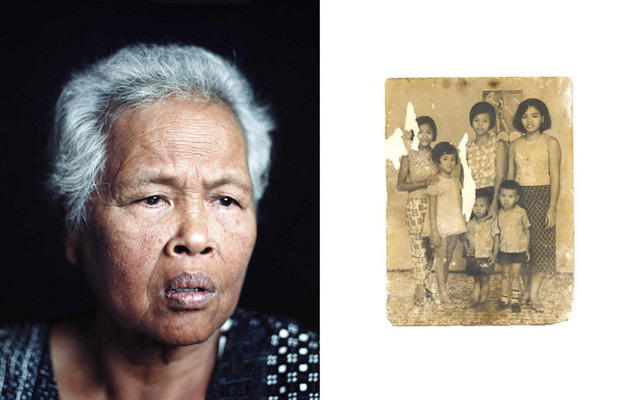

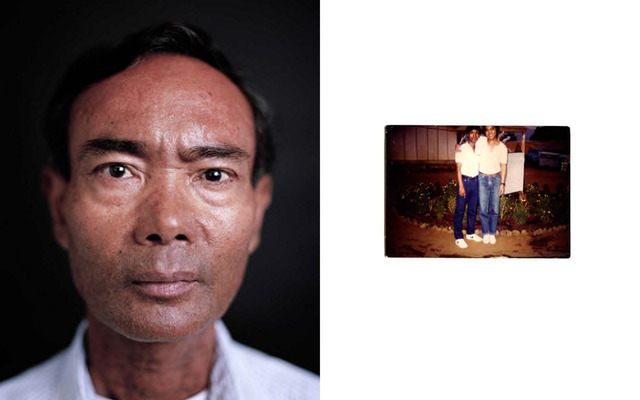

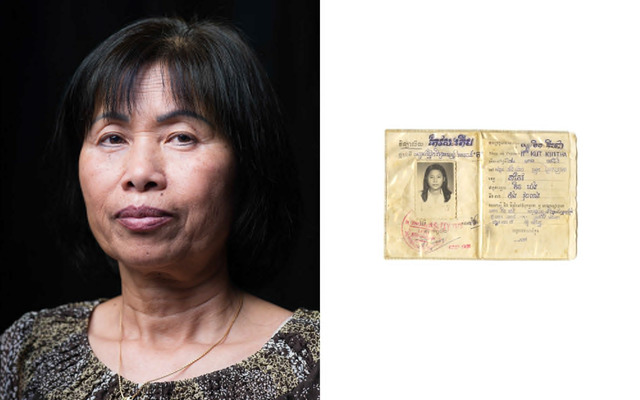

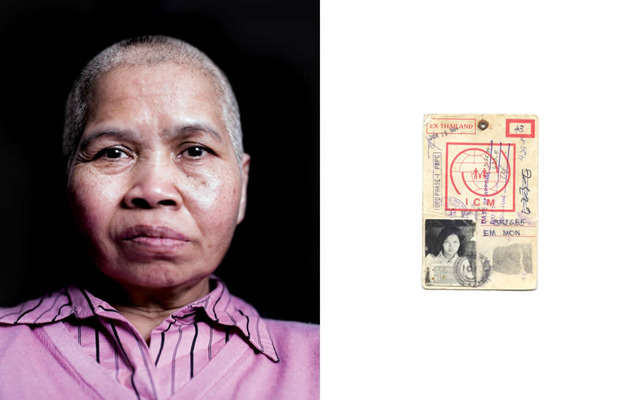

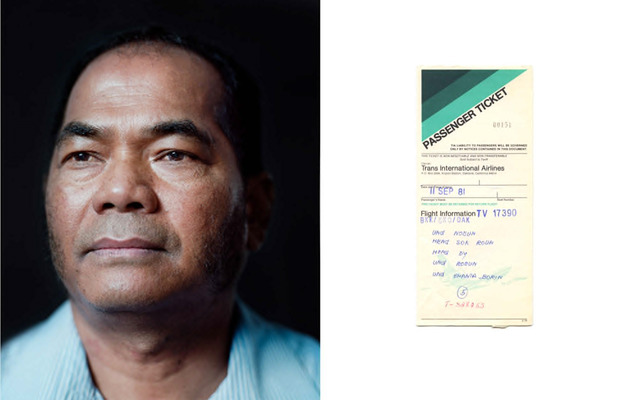

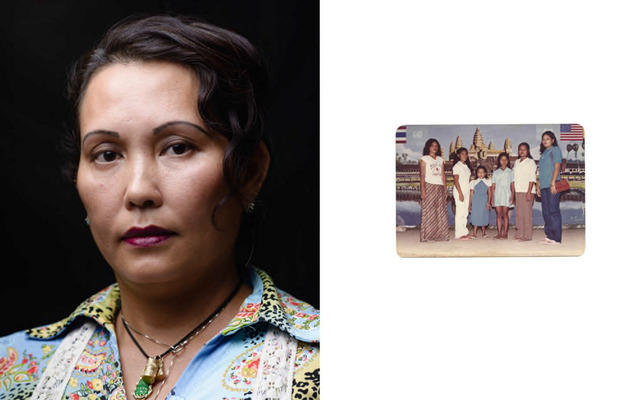

Amy Lee Sanford, video still from Cascade (36), 2014, single-channel, 11 min, 47 s. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSACWhereas Sanford’s work has its basis in personal contemplation, Pete Pin uses photography as a process for civic engagement and a catalyst for intergenerational dialogue among Cambodian-American families across the United States. Pin was born in 1982 in the Khao-I-Dang refugee camp, on the Thai–Cambodian border, and migrated to California in the mid-1980s. Inspired by his family’s story, Cambodian Diaspora: Memory (2010–) is a series of diptychs comprising a newly photographed studio portrait of a Cambodian refugee immigrant and an archival document. Produced mainly during the transition of immigration, these old documents — among them photographs taken at refugee camps, plane tickets, and other ephemera that constitute a tangible historical record — are collectively chosen for Pin’s photographs by members of each depicted family.

According to the photography theorist Ariella Azoulay, photography is a universal “civil contract” in which all human agents involved — that is, the photographer, the photographed, and the spectators — are equal individuals with inalienable rights.[2] She argues that “[p]hotography is an apparatus of power that cannot be reduced to any of its components: a camera, a photographer, a photographed environment, object, person, or spectator.”[3] In other words, it cannot be limited to or contained by any of these agents. Azoulay contends, too, that photography always constitutes an event, or what she calls the “event of photography.”[4] This event, not the photographed event, according to Azoulay, is an ongoing, boundless, discursive event in which the photograph is articulated, referred to, viewed, circulated, defined, redefined, and given meaning.[5]

By initiating the process of reviewing and selecting the archival materials, Pin facilitates the generation of a new discursive space, or an “event of photography,” in which parents and children engage in discussions about difficult histories and pass on memories. We might consider this process of dialogue to be an “event” of Pin’s photography. The later encounter of Pin’s printed diptychs with an exhibition audience constitutes yet another “event” in the continuing life of his photography. At each event, private family archival images once again become accessible while being rearticulated.

Pin’s diptych series is a documentation of the present and the past. The contrast between the black background of each newly produced portrait and the white background for the image of the archival document evokes a feeling of tension between an ostensibly fading present and a resurfacing memory. This juxtaposition of and conversation between the present and historical moments suggests a dialectical, transitory path that is in constant movement, back and forth, yet waits to be recirculated and rearticulated.

Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2010, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2010, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2010, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2010, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2014, archival pigment print, 91 x 15 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2014, archival pigment print, 91 x 15 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2014, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2014, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2013, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2013, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2013, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2013, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2014, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Pete Pin, Untitled, from the series Cambodian Diaspora: Memory, 2014, archival pigment print, 91 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSACSeoun Som was born in 1979 in the Sa Kaeo II refugee camp, on the Thai–Cambodian border, and resettled in Australia in 1986. Raised in Adelaide, Som later moved to the United States. In Devoid of Presence (2009), the artist presents manipulated black-and-white photographs printed on sheer fabric to convey his state of transience among worlds. By overlapping images of religious rituals associated with death from the United States with shadows of those from Cambodia, Som questions and challenges the notion of a fixed identity for a world-crossing citizen.

Som’s work should be viewed and experienced in a physical installation, as audiences are invited to walk among several large works, suspended parallel to one another in space. As we move through the installation, we somewhat become absorbed, merged, and chameleonic within layers of semitransparent images; what we see continuously varies, making it impossible to perceive or define a fixed state. This persistent shifting of perpetual adaptation of identity denies us a familiar and secure sense of being, raising questions of who we are in a world of relentless mobility and migration.

Sanford, Pin, and Som exploit and challenge photography as a medium, as a process, and in its very materiality. They interrogate photography as an image-capturing tool, photography as documentation and facilitation of discursive space, photography as a visual and bodily experimentation. Sanford’s use of a scanner — as a device to almost literally “scan” history — may not fit comfortably within our usual understanding of the photographic medium, one that involves cameras; however, the extent to which she employs the scanner as an image-capturing device poses the question of photography’s technical domain.

In activating personal biographical reflections, the artists offer diverse approaches to possibilities in articulating histories, facilitating social relations, and challenging notions of identity. Although these bodies of work are very much rooted in each artist’s autobiography and personal experiences as Cambodian-American diasporic citizens, they speak to diaspora communities worldwide.

Seoun Som, Devoid of Presence 1, 2009, dye-sublimation on polyester chiffon, 152 x152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Seoun Som, Devoid of Presence 1, 2009, dye-sublimation on polyester chiffon, 152 x152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Seoun Som, Devoid of Presence 2, 2009, dye-sublimation on polyester chiffon, 152 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Seoun Som, Devoid of Presence 2, 2009, dye-sublimation on polyester chiffon, 152 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Seoun Som, Devoid of Presence 3, 2009, dye-sublimation on polyester chiffon, 152 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Seoun Som, Devoid of Presence 3, 2009, dye-sublimation on polyester chiffon, 152 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC Seoun Som, Devoid of Presence 4, 2009, dye-sublimation on polyester chiffon, 152 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSAC

Seoun Som, Devoid of Presence 4, 2009, dye-sublimation on polyester chiffon, 152 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and SA SA BASSACAmy Lee Sanford lives and works in Phnom Penh and New York City. She holds a BA in Visual Arts from Brown University. Recent solo exhibitions and performances include Break Pot Performance: Gertrude Street, at Seventh Gallery, Melbourne (2013); 40 Pots + 4 Sketches (2013) and Full Circle (2012) both at Java Arts, Phnom Penh. Recent group exhibitions include 1975 at Topaz Arts, NYC (2013); new artefacts at SA SA BASSAC, Phnom Penh (2012); and the London Biennale (2008). Sanford was an artist-in-residence at Lower Manhattan Cultural Council as part of Season of Cambodia 2013.

Pete Pin, who lives in New York City, holds a BA from the University of California Berkeley and studied documentary and photojournalism at the International Center of Photography, in Manhattan. He was a 2011 Fellow at the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund, named an Emerging Talent in Reportage by Getty Images, and an artist-in-residence at the Bronx Museum. He served as curator of Forward: Modern Arts Festival (2013), a group exhibition of Cambodian diasporic artists at Gowanus Loft, Brooklyn. His work has been published in the New York Times, Time, Forbes, and Burn. Pin is now working on a long-term project with different Cambodian diasporic communities across the United States.

Seoun Som lives and works in Ohio. He holds a BA from Youngstown State University in Ohio and a MFA from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His most recent solo exhibition was Devoid of Presence, Ohio University, Athens, OH (2013). Group exhibitions include Forward: Modern Arts Festival at Gowanus Loft, Brooklyn, NY (2013); Come Out and Play Art Festival, Pittsboro, NC (2012) and Plugged In at Lump Gallery, Raleigh, NC (2011). Som also taught photography at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 2010-12.

Vuth Lyno is an artist, curator, and Artistic Director of Sa Sa Art Projects, Phnom Penh’s only experimental artist-run space. He was Curatorial Assistant for IN RESIDENCE, Visual Art Program of Season of Cambodia 2013, NYC, and Visual Art Curator for Cambodian Youth Arts Festival 2012. He exhibited in the touring exhibition RiverScapes IN FLUX (2012) and ROUNDTABLE, Tobias Rehberger Pavilion, ‘You Owe Me. I Don't Owe You Nothin.’, Gwangju Biennale (2012).

Notes

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History” (1940), in Selected Writings, Volume 4, 1938–1940 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2003), 391.

Ariella Azoulay, “The Ethic of the Spectator: The Citizenry of Photography,” in Afterimage 33, 2 (September/October 2005): 39.

Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York and Cambridge, Mass: Zone Books, 2008), 85.

Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (London and New York: Verso, 2012), 26.