Photography and Diaspora: A roundtable with Pok Chi Lau, Surendra Lawoti, and Wei Leng Tay

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The classic features of diaspora are a history of dispersion among a people (whether forced or voluntary); a strong sense of a homeland from which those people have been dispersed; a desire to return to a place of origin (however fantastical, impractical, or impossible that wish might be); and a lack of full assimilation in a host country. In today’s world, in which the coming and going of peoples is extraordinarily fluid, in which “home” can be fractured or multiple, and in which, in a few countries, including those in the throes of postcolonialism, the goal of assimilation competes with the recognition (occasionally the celebration) of cultural difference, is diaspora still useful as a description? Does it help us to understand contemporary photographic practices that pursue the experiences and longings of a migrated people?

Following is a brief roundtable among three photographers who address these and other questions. In a sense, the photographers’ own movements reflect aspects of diaspora. Each was born in one country, moved to another, and return frequently to photograph the peoples and lands of their birth. They interpret their practices extraordinarily differently from one another, however, and use their cameras to different purposes and effects. In their hands, the features we associate with diaspora are often put into relationship with other ways of describing the movements of people, the forces of “home,” and the dynamics of assimilation.

Pok Chi Lau was born in Hong Kong and now lives in the United States; Surendra Lawoti was born in Nepal and now lives in Canada; and Wei Leng Tay was born in Singapore and now lives in Hong Kong. Our conversation moved fluidly between the photographers as themselves diasporic and their interest in people who might be said to belong to a diaspora.

Anthony Lee: Since we’re gathered to talk about photography and diaspora, let’s start with a general question. Do you consider yourselves diasporic photographers?

Pok Chi Lau: I ended up being one without trying to. I didn’t even know the word diaspora existed until I came to KU [the University of Kansas]. Jewish studies people were using it. I learned about it in the late 1980s and it described what I was doing instinctively. I was traveling out of the country a lot, sometimes eight months of the year. When I traveled, I always found Chinese living abroad, and I always photographed them. I didn’t always travel with the intention of finding them, but there they were; and they always approached me and wanted to tell their stories to me. They were a scattered community, and they had their own rules. The idea of being Chinese was important to them.

Surendra Lawoti: I am both a diasporic and a transnational photographer. They are close but there are some differences in the way I understand the words. Transnational is little connected to nations or even nationalism. For me, transnational is more associated with ideas of national borders, border crossings, and multiple national identities. Someone could be diasporic and not be transnational. I am choosing to refer to myself as transnational because I am quite engaged with Nepal while living in Canada, and also am engaged with Canada.

Wei Leng Tay: I don’t think of myself as a diasporic photographer. I actually think the term “diaspora” is problematic. Hah!

AL: That’s quite surprising. Your projects are so often concerned with the Chinese living in places other than China who maintain a strong sense of their Chinese-ness.

WLT: When people look at my work, the assumption is often that my interest is in the Chinese diaspora. But I find “diasporas” and their references limiting.

AL: How so?

WLT: My work in Southeast Asia focuses on areas that are relatively young, with some postcolonial countries that have had to rely on nation building to bind disparate ethnic groups, and in my opinion the forces of a more recent history of nation building supersede the influence of the original homeland. In my interviews with people during my projects in Singapore and Malaysia, some gave me blank looks when I asked about connections with China. One older gentleman, when I asked him what he thought of our links to China now, said, “Money.”

AL: That’s interesting. And so their being Chinese is more strongly an ethnic affiliation in the here and now; and do they keep to the language, too?

WLT: Yes, but let me give an example. I photographed in Bangkok for a few weeks a few years ago. The project was a mapping of the lives in a small street. When I first started photographing, people would talk to my assistant in Thai and not really talk directly to me. But as the days passed and they realized I was just this harmless person, and that I was Chinese, and their neighbors started letting me photograph them, others would come up to me and start speaking to me in Mandarin! They would show me their ID cards, tell me what their Chinese names were — everyone officially has a Thai name. It was mindboggling. The neighborhood morphed in front of my eyes, from one that was totally foreign to a Chinese one. It changed my understanding of Bangkok, not of a Chinese diaspora.

AL: Pok Chi, you’ve had similar experiences about being approached, but you interpret them differently, no? I’m thinking of your Cuban work, in which you photograph sitters holding portraits of their Chinese ancestors.

PCL: I got the idea from a man who ran a hostel when I was traveling in Santiago de Cuba, in eastern Cuba. He was the son of a Cuban man, but his father left the family, and he was raised by a Chinese man living in Cuba. Mind you, he had no Chinese ancestry but was merely raised by this Chinese man; they had absolutely no blood relations. And the whole experience of being raised by this man meant a lot to him. After he served breakfast, he pulled a picture out of his wallet of his adopted father. This little black-and-white passport picture was moist from years of sweat and humidity. As he showed me the picture, his lips were trembling and his voice choked up. In tears, he held the picture on his heart. Here was a man who had no Chinese blood but identified himself as the son of a Chinese man, and he cried thinking about his “ancestor.” And so I began a series of portraits of Cuban Chinese holding pictures of their ancestors. The ancestors were important to them and gave them a sense of belonging to something, as if they had a different value.

AL: You mean a different sense of self-worth from the one given to them in Cuba.

PCL: Yes. When I went to Cuba, I was shocked by how much the Chinese Cubans wanted me to know about their lives. They were desperate for contact. They felt so cut off. They came to me and wanted to tell me their stories about their families. I never went to them. None of them had been to China, but they all identified as Chinese. Some of them didn’t even look Chinese; you would never guess they were. But they held on to these portraits and identified themselves with the people pictured in them. And a lot of them cried when they talked about those people. It was powerful to me. I met a man named Pedro Eng, a mixed-race Cuban. He had never left Cuba, and although he had never been to China, he thought of it as his home. So in May 2014 a few of us put together some money and bought him a plane ticket. It was like a homecoming to him; he said it was like a dream.

AL: So, for you, the ancestor photos affirmed the Cubans’ sense of living in the diaspora, even if it was, as in the case of the adopted man, a completely imaginary one. This is quite the opposite of Wei Leng’s experiences, though it sounds as if “money” is also involved somewhere.

PCL: I think China is important to them because conditions are so rough in Cuba. The ration books they each live by don’t give them enough food. They want to believe in a better life and better times. And the Chinese in them represents that, even to those Cubans who, like the man who was adopted by a Chinese man, were not Chinese at all. Chinese food really mattered to them. When I went back for another visit, I brought fifty pounds of dried plums to give to the people I had met. There were many people who took a plum and kept working it in their mouths, pushing it to the left side of their cheeks, then to the right side, over and over again, until their tongues got blisters from the pit. They didn’t want to give up that plum. This stemmed from their childhood experiences watching Cantonese operas in theaters. Sucking salty, sweet-and-sour plums was a common experience — even a diasporic experience. Pedro had a whole bag of plums while in Hong Kong. His eyes lit up from that memory.

WLT: For my projects in Singapore and Malaysia, the people I photographed are first, second, and third generation and think of themselves as Singaporean or Malaysian first. I think most people I photograph don’t think about belonging to a diaspora, and definitely do not see China as the homeland. On the contrary, China is often a faraway place that one thinks about with the help of the media, or the place where the new migrants, who are going to the countries I photograph in, come from. They do keep to traditions and celebrate festivals and such, but my work is usually not about those aspects of Chinese culture.

AL: And those traditions and festivals would have far more local ethnic meanings anyway.

WLT: Yes, for Malaysia and Singapore specifically, race politics is an undercurrent in people’s everyday lives. In Singapore, it is institutionalized in housing policies, in education, and in official identification. In both Singapore and Malaysia, there are strong stereotypes about the different races — the word race is historically the term officially and predominantly used — that are vestiges of colonial rule and the nation-building rhetoric from the mid- to late twentieth century. The government has recently started using “ethnicity” as its preferred term.

AL: And yet, as you say, although Singapore has had a long history of migration from China, that history is not an inheritance that appears in the Chinese sense of self.

WLT: I’ve chosen to focus on the Chinese as a group to photograph because I am Chinese, and also I wanted to explore the results of living within our political and social environment and the resultant “othering” of groups in the specific local contexts. I believe that in Singapore and Malaysia, our political construct has been much more important in shaping people’s identity in terms of ethnic identity than has their existence within a diaspora.

You yourself have done extensive research with Chinatowns, and I wonder if you have anything to say about this.

AL: That’s true, I’ve worked on historical photographs of Chinese living in the United States: San Francisco in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and North Adams, Massachusetts, in the 1870s. If you were to ask the Chinese in North Adams about their experiences, they probably would’ve answered with a set of descriptions that sound a lot like the ways we describe diaspora. Their contemporaries would’ve used other words — sojourning was popular — but the general feeling was that their homes were somewhere else. They traveled to the United States to make money but their obligations were to their families in China; and they imagined that they’d one day return to them, even if that was a lifetime away. And I think a good many of them held on to that commitment even if, in the end, they settled in the United States and never returned.

But — to connect with something Surendra said about the awareness of national borders and what you said about the trappings of nation building — I’d also say that some of the biggest differences between then and now have to do with the nature and integrity of “home.” The diasporic Chinese in the 1860s and 1870s almost all came from Guangdong, in southern China, which had an extraordinarily strained relationship with China itself. If you were to call the young men “Chinese,” they would not necessarily have understood what that meant or, maybe better, would’ve dismissed that in favor of some other identification, much more local, much more village- and dialect based, where family names mattered a whole lot. It led to a situation in which some of the men felt only very loose bonds with one another. Ethnic politics certainly figured in the way the young men dealt with Americans, but also in the way they dealt with each other.

Surendra, your projects — I’m thinking of the photographs of the Nepalis in Chicago — understand ethnic identity in a more traditional diasporic way.

SL: Well, I understand the word diaspora as it is meant in English.

AL: Is there another understanding of that word in Nepali?

SL: Hmm, that’s an interesting and good question. Pravasi in Nepali (also in Hindi) is the closet word to diaspora. Pravasi refers to people who have left the original country to live in another country. But global migration is a very new phenomenon to Nepalis, unlike the Chinese phenomenon you and Pok Chi and Wei Leng are interested in. Lately, there’s been lot of migration to the Gulf countries, Malaysia, Korea, Japan, and others, but for remittance, so much so that Nepal’s economy is being sustained by remittances sent by the migrant workers. These migrant workers work in the host countries but they do not or are not allowed to settle permanently. Hence, these people do not quite fit the “diaspora” category. Not directly related, but expats is a highly used word and a relevant word in Nepal, as there are many Western expatriates who work for the mushrooming NGOs and INGOs in Kathmandu. These expats are generally very well paid in comparison to their Nepali counterparts and live comparatively lavish lifestyles. So there is a difference between pravasi and expat, at least in the Nepali mentality.

AL: That’s an important distinction. So the Nepalis in your projects do not or cannot stay? They’re pravasi?

SL: I should clarify for our readers: there are two related projects I have on the Nepali diaspora. The first is called Chicago Pictures and the second is Pictures from the Nepali Diaspora. Chicago Pictures was photographed within a small segment of the Nepali community, whereas Pictures from the Nepali Diaspora was photographed in Boston, Chicago, and Michigan. As I say, they are related, but there are slightly different conceptual concerns. In the case of Pictures from the Nepali Diaspora, I was interested in the migratory experience of Nepalis living in the United States, and in this sense it’s very much about the diasporic experience. It’s really about the interiority of the migratory landscape.

AL: Can you say more about the differences between the two, and also how they relate to this idea of staying?

SL: Chicago Pictures and Nepali Diaspora are like part one and part two of the same project, Chicago Pictures being the first part. Chicago Pictures was the first project that I worked on after completing my undergraduate studies in art school. It was a very important project, as I was figuring out lots of things, both artistic and personal. The project was really about assimilation to America. It incorporates living spaces, portraits, and social events to tell the recent immigrant experience that I shared with my Nepali friends in Chicago. Nepali Diaspora is less about assimilation and more about longing and belonging. In Chicago Pictures I was asking questions such as “Do I belong here in America?” and “Do I want to stay here permanently?” In Nepali Diaspora I have realized that I am stuck here and it is about that realization and the introspection that comes in between. Also the visual language is more developed in Nepali Diaspora.

AL: Tending more toward an expanded idea of portraiture, it seems.

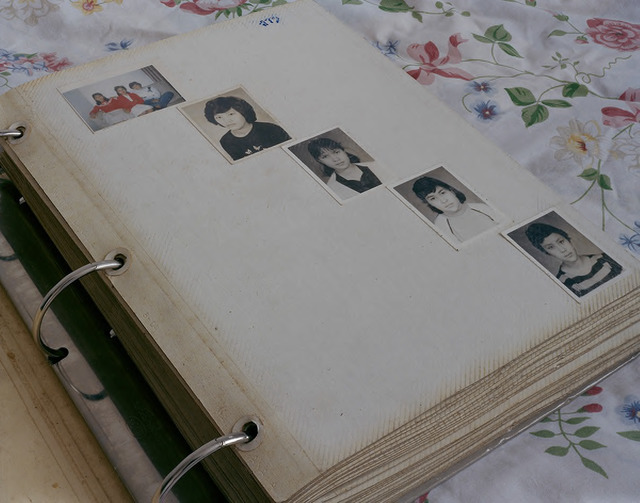

SL: I wanted to incorporate portraiture because the work dealt with the identity of specific people. As the work developed, I wanted to expand the idea of portraiture by photographing living spaces and personal objects. Obviously when you photograph empty spaces — domestic, in this case — there is a sense of absence and loss, which is also part of the work. And much of the migratory landscape is about home. So the work alternates between people’s faces, their living spaces, and their objects. Images flicker back and forth, like memories. The work tries to evoke the intangible aspects of longing and the sense of belonging. The work is certainly about people, and hence they are portraits. But it’s not portraiture in the traditional sense. Traditionally, portraiture focuses on faces and body image. I was more interested in the interiority and less on the facades.

Fig. 5. Surendra Lawoti, Photo Album, from Pictures from the Nepali Diaspora, 2003, courtesy the photographer.

Fig. 5. Surendra Lawoti, Photo Album, from Pictures from the Nepali Diaspora, 2003, courtesy the photographer. AL: So I’m struck that some sort of portraiture — let’s call it that for now — appears importantly in each of your investigations. The historical effects on people seem best addressed in that way?

WLT: I don't really think of my work as portraiture; I just photograph people. But the work could be construed as portraiture, just not in the traditional sense of having someone posed for the shot. I think my work tells you about the people in the photo. The environment, the things, their dress, the body language, how they touch each other: all of that comes together to tell you very much about the people, which is what a portrait is about. I don’t like to tell people what to do, as I think how they choose to be in a photograph, what they choose to show, and how they choose to present themselves make the work even more powerful and also more of a collaborative process.

Having said that, the work is never purely a reflection of the people in the photo.

Fig. 6. Wei Leng Tay, Hoi Yan and family, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, from Convergence, 2010, courtesy the photographer.

Fig. 6. Wei Leng Tay, Hoi Yan and family, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, from Convergence, 2010, courtesy the photographer. AL: What do you mean by that?

WLT: The artist’s intervention through the process of photography — the frame, the location, the emotion, and the editing process afterward — makes it impossible for images to be considered purely documentary, or the “truth.” The projects I embark on usually touch on themes of family, relationships, and society because these are things I think about a lot for myself. My own experiences, opinions, or perhaps biases on these matters influence my choice of the edit, framing, and moment or emotion in the image.

AL: For both of you, the pictures of people should alternate with pictures of “home.” I’m curious about that because for many who settle in different parts of the world, the very reason to migrate is for “work.”

WLT: I like photographing people in their homes because we get to see how they live, which tells us so much more about them than if we were to see them outside. Also, people behave very differently in the home than they do outside. I’ve photographed people I’ve known for years where upon entering their home, I see a whole different dynamic between the couple and way they treat each other that reflects the power relationship and anxieties they’d never allow people to see in public.

Another example to illustrate my point is that seeing and interacting with people in their thirties outside and then going to their homes and seeing that they still sleep in their childhood bedrooms surrounded by objects and toys from their youth — all this is fascinating, and brings out many more layers in the people, and also makes me see them very differently in thinking about how they see themselves. It also makes me think about the societal construct, family duty, and hierarchy, and that feeds into how I think about the projects.

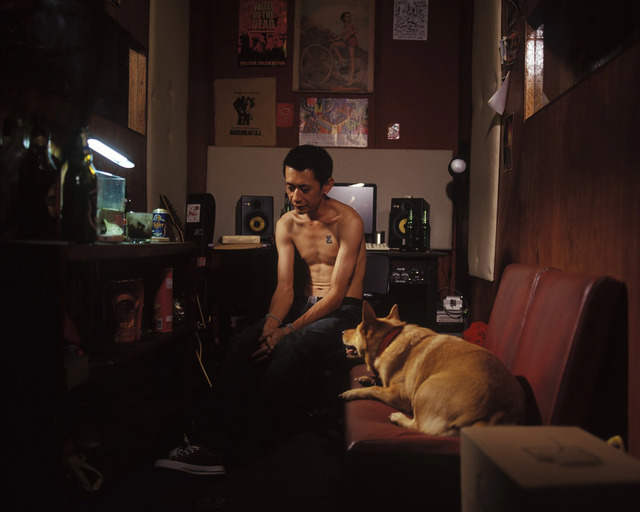

Fig. 7. Wei Leng Tay, Untitled 3, Singapore, from Slow Cool Breezes, 2009, courtesy the photographer.

Fig. 7. Wei Leng Tay, Untitled 3, Singapore, from Slow Cool Breezes, 2009, courtesy the photographer. AL: But whereas in your photos the homes are full of “things,” Surendra, as you said, there’s an almost melancholic empty space in yours, as if “home” is much less situated.

SL: Recent migrants don’t have fixed dwelling spaces. Everything is temporal; nothing is grounded. I did not necessarily choose to photograph spare spaces. The spaces themselves were spare. Recent immigrants often move to apartments between cheaper, yearlong leases. They buy cheap collapsible closets at Target to store clothes. When your dwelling space is not fixed, life itself is temporal. After recognizing these things, I decided to include the sparseness as a visual strategy.

AL: Do these kinds of experiences resonate with your own?

WLT: There are definitely shared memories and experiences. Singapore is a very small country. The projects are often journeys for me, discovering these shared experiences and trying to figure out why we do what we do, why we have stereotypes, et cetera. I haven’t properly lived in Singapore since 1997. I go back a lot to do projects and visit. I think this distance gives me perspective. I’ve lived in Hong Kong for the last fourteen years and have mostly been considered a foreigner, even though I am Chinese. This “othering” has definitely been a reason for the projects I do.

SL: My experiences are similar to those of my subjects, although we can each relate to or deal with them differently. But some are very common. We all miss certain food. Invite any Nepali to a momo [steamed dumplings] party; their eyes will gleam with joy. A clear day with blue sky in New England in September can remind of you of Dashain festival [the biggest festival in Nepal], as weather and lighting conditions can be similar. Difficulty with English, feeling alienated, and working low-paying jobs are more of the practical experiences for new migrants.

AL: Pok Chi, you were born in China but then left at a young age, and like both Wei Leng and Surendra, you’ve returned frequently. Are those senses of familiarity-but-distance and recognition of otherness that Wei Leng identifies motivations for you as well? I’m thinking of your Diaspora within China project, which, to help our readers, was one of the first projects you did after you returned.

PCL: I was born in 1950 in Hong Kong, then a British colony. I left in 1969 at the height of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, which I never witnessed. I learned that millions of Chinese during the revolution were forced to relocate, some permanently, many far away from home. That fascinated me. I entered mainland China for the first time in 1979, after getting U.S. citizenship. My goal was to understand and portray how people lived in such changed circumstances, even oppressive conditions. Chairman Mao was an immense figure; it was shocking to see his portraits hung in living rooms and family shrines, replacing ancestral altars, an act that uprooted thousands of years of traditional Chinese culture. I also found Zhou Enlai’s portraits among tiny ancestral altars in bedrooms.

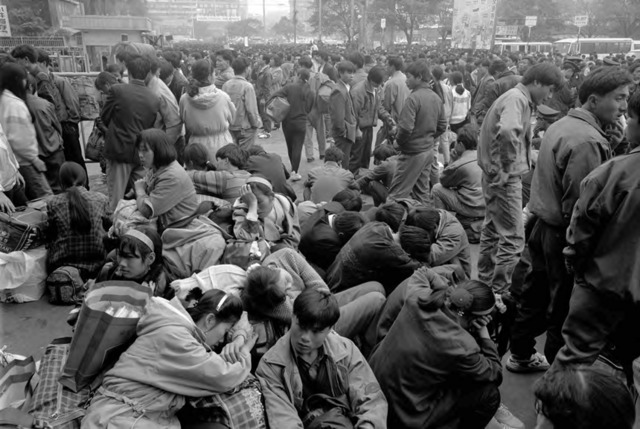

In the early 1980s, the Chinese living in the countryside tried to move back to the cities to find jobs and families, but by the late 1980s, the flow reversed. The migrant workers lived in the cities year-round, except for Chinese New Year, when they returned to their villages. The train stations during the New Year were packed with workers returning home to remote parts of China. The need to go home was strong, but the workers always returned to the cities and spent almost all of their lives away from their villages, even though the people in the cities didn’t always accept them. They were “othered” and lived in tents next to industrial dumpsites. Their children were not allowed to attend regular city schools. They lived in small communities with other villagers they knew (like Taishan Chinese folks in the United States in the 1900s), and those without proper documents and permits took bad factory jobs and got bad pay. They just flowed back and forth.

Fig. 8. Pok Chi Lau, Homebound workers before the Chinese New Year at railroad station, 1994, courtesy the photographer.

Fig. 8. Pok Chi Lau, Homebound workers before the Chinese New Year at railroad station, 1994, courtesy the photographer. AL: Ah, that’s why you called your book Flow China.

PCL: That’s right.

AL: Some people would say that such a thing — diaspora inside China — complicates our sense of diaspora because it entangles it with internal migration, and that “diaspora,” in the classic sense, sometimes too narrowly describes it as living abroad, across national borders, within an experience of radical difference — of language, of culture, of skin color.

PCL: If that isn’t diaspora, I don’t know what is. I wanted to photograph all of that. It was a story that needed to be told. China is such a vast country with such diverse ethnic groups. Imagine the Han Chinese being sent to Tibet and Xianjiang during the Cultural Revolution; they were complete foreigners in their own “country.” In different historical times these areas were not part of China. Another example is Shenzhen, a city just north of Hong Kong. When I first photographed there, it was a tiny town made up of farmers and fishermen. Folks spoke Hakka and Cantonese dialects. Now, with so much new since 1980s, you hear hardly anyone speaking Cantonese.

But let me talk more about my relationship with their stories. The focus of my work in 1979 and 1981 and 1982 was an investigation of how political movements in China forced people to migrate. Because I was telling those stories, in 1981 I was blacklisted. I learned I had been blacklisted through a Hong Kong publisher. I was publishing stories with my photos about the internal diaspora, and suddenly my stories stopped getting published. I learned from the editor that the magazine’s owner was also a wealthy and powerful wholesale rice merchant who got his goods from China, and he regarded my point of view as “insulting the leader.” After that, I felt I was in danger and stayed away for two years. I returned to China in 1984 to take more photographs. One day in Shenzhen I was in an alley photographing broken class that had been cemented onto the top of a wall — not migrants — and I was approached by two men who identified themselves as policemen. They followed me back to my hotel lobby to check my passport and wanted to know what and why I was photographing. I told them I was working for a Hong Kong boss looking for real estate to open a factory! They let me go without pulling my film. But I didn’t go back to China after that summer for a long time, not until 1994, when migrant workers were moving big time. I hid my camera, and I carried my tripod in a nondescript bag.

AL: That’s a great story, though I don’t know if you can still pass as a real-estate investor! Maybe we should talk about the camera decisions you each make when trying to delve into such politically and socially complicated projects. Surendra, I see that in your new work in Nepal, you’re handling the camera differently from how you did in the Chicago and Boston projects.

SL: To connect to your very first question, I would say This Country Is Yours is from a transnational perspective and Nepali Diaspora is from a diasporic perspective. Whereas Nepali Diaspora is about the migratory experience of Nepali people living in the United States, This Country Is Yours is really about Nepal but done by a Nepali who is from the diaspora. Although they have a relationship, the two bodies of work are quite different. They require different thought processes and methodologies.

AL: Just to be clear for our readers, This Country Is Yours is a project based in Kathmandu. You’re interested in picturing the people and processes associated with writing Nepal’s new constitution. And in particular you’re interested in photographing those populations that are in danger of not being included in the constitution’s provisions, of being written out of the new Nepal, as it were: religious minorities, women, LGBTs, indigenous populations, and others.

SL: Yes, that’s right. This Country Is Yours is quite political and requires extensive research. Because the conceptual frameworks for the two projects are different, the cameras are used differently. I have tried to come up with aesthetics suitable for each body of work. Having said that, there will always be similarities in the picture making and camera usage between different bodies of work. As I said before, Nepali Diaspora was very internal. It spoke about the interiority of the migratory experience a lot more and it was also quite melancholic. I knew most of the people in Nepali Diaspora and generally I was meeting the participants of This Country Is Yours for the first time. Hence, the interpersonal dynamics were different. Nepali Diaspora is within people’s domestic spaces and the photographic process was more relaxed, whereas This Country Is Yours was done in office spaces, domestic spaces, and even public spaces, and it required appointments, sometimes with very busy people.

AL: Your camera has changed too.

SL: I started with a medium-format camera for the Chicago Pictures. But after a year of using a medium camera, I was not quite happy with the results. Some of the earlier images from Chicago are more spontaneous. Then I switched to a large-format camera after the first year and I have been using it ever since. For This Country, I use a 4x5 view camera and color negatives. The view camera engages with the subject matter in the manner that I prefer, which is slower and more deliberate. The photographic process with the view camera is more considered and thoughtful, and it records with the utmost clarity.

AL: That makes me think of your photograph of Radjev Kumar Khang. Thoughtfulness and deliberateness are not only characteristic of the photographic process but also seem to be things you wanted to thematize in that picture.

SL: Radjev Kumar Khang is an exception to the way I’m approaching portraiture in This Country Is Yours. In This Country, I was trying to make portraits of these activists somewhat formally but without being overtly didactic. I wanted the portraits also to be somewhat personal. I was incorporating both living spaces and affiliated office spaces to make the portraits. I photographed Khang in his small, one-room apartment. He was a master’s student in population studies in Kathmandu. He is lying on his bed. I asked him to lie down on his bed and look up in intense thought. I like the closeness of the camera to his body and his face. It’s perhaps the most intimate portrait of This Country Is Yours.

Fig. 9. Surendra Lawoti, Radjev Kumar Khang, Central Member, Madhesi Students Forum, Nepal, from This Country is Yours, 2013, courtesy the photographer.

Fig. 9. Surendra Lawoti, Radjev Kumar Khang, Central Member, Madhesi Students Forum, Nepal, from This Country is Yours, 2013, courtesy the photographer. AL: Do the interviews affect the camerawork?

SL: My current work for This Country Is Yours requires a lot of interviews for research. I want to understand the issues associated with a particular activist and his or her activism. The project is a little problematic in terms of showing the work to a non-Nepali audience. The work is very specific to Nepal’s history and politics. The work needs context. Hence, I have started using the interviews with the images to provide context for the work to a non-Nepali audience. The photographs themselves work on one level, but if people want to delve further, they can also read the interviews.

Fig. 10. Surendra Lawoti, Prem Kumar Sunuwar, International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples celebrations, from This Country is Yours, August 9, 2013, courtesy the photographer.

Fig. 10. Surendra Lawoti, Prem Kumar Sunuwar, International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples celebrations, from This Country is Yours, August 9, 2013, courtesy the photographer. WLT: For my work, I think the more localized the audience, the more the significance of objects, gestures, or the presence or absence of people or things resonate with them, and the more nuanced the reading. On one level, one can easily see the relationships and lifestyles, but a local viewership can pick out objects, even window types, that allude to the situation and class of the sitters. From gestures they can identify the kinds of relationships that are depicted, and infer more within the local social context.

AL: Can you give an example?

WLT: Many years ago, I was showing my work to a curator in the United States. The person asked why so many of my photos had these standing fans in them and why I included the fans in the photographs. The person had thought the fans were unnecessary. For me this was a minor point, but Singapore is hot year-round, and these fans are in most households, especially older ones, where people, like my mother, are thrifty and unwilling to spend more on having the air conditioning on all the time. In a younger middle- or upper-middle-class home, perhaps the fan would not be as ubiquitous. A small detail, but there’s something to be said about how an everyday object as simple as the standing fan can illustrate economics and generational shifts.

But on a broader scale, a foreign audience can often see what the local audience has inured itself to, and perhaps better see the dysfunctions of the group.

Fig. 11. Wei Leng Tay, Kian Foo's Home, Penang, Malaysia, from Convergence, 2010, courtesy the photographer.

Fig. 11. Wei Leng Tay, Kian Foo's Home, Penang, Malaysia, from Convergence, 2010, courtesy the photographer. AL: Back to the interviews, do they function in the same way for you as they do for Surendra?

WLT: Interviews are integral to my work, and have often shaped its direction. For example, in my current project about mainland Chinese in Hong Kong, the interviews changed the way I think about the entire situation, and made me adjust the way I photograph the project.

In exhibitions, the interviews are edited and made into sound interventions removed from the specific sitters who made the specific comments. I make a conscious effort to divorce what’s said from individuals. The opinions, background, and experiences the sitters bring up add another important dimension to the projects, and come together to provide a social, political context to the photos. The interviews have also been used in write-ups, in reviews, and also in my book to add another layer to the entire work.

AL: That’s interesting. So the voices are intentionally disembodied and, although different from Surendra’s, they function like a context. This is very different from Pok Chi’s way with interviews. They’re directly attached and are not so much about context — although they provide that — but more about the experiences of specific individuals.

PCL: Yes.

AL: And that direct connection structures the camera work. I’m thinking of your new work now, about the Chinese in Myanmar.

PCL: The Myanmar photographs don’t have the attraction of some of the other projects. It’s more documentary, but it’s a story — about the Chinese living in north and central Myanmar — that also needs to be told. As in Cuba, the Burmese Chinese are identified as Chinese, even those who were born and raised in Myanmar. That means they’re second- and third-class residents, not citizens. I met a Taishan Chinese Burmese man in his forties who worked in a Detroit sushi bar for two years and then decided he’d had enough of America and returned to Myanmar for a better living. One night, and only at night when spirits arise, he had to speak to his deceased grandparents and an uncle to tell them to pack, as their bones would be dug up and relocated at daybreak. He spoke to them through a woman who knew rituals and traditions. (He drove me and two gravediggers in a Lexus SUV, a rare species in Myanmar.) These are the kinds of personal stories I want to document.

AL: So, whereas the Cuban Chinese identify as a way to offer themselves an alternative to the Cuban situation — now I’m recalling your story about the plums — the Burmese have different desires.

PCL: The difference between these people in Myanmar and the Cuban Chinese is that the Burmese Chinese are better off economically, so the motivation to keep an ethnic affiliation is different from what is it is for the Cubans. And most of the Burmese Chinese have no desire to live in China. For some of them, the quality of living in China is lower than it is in Myanmar, and they’d never return “home.”

AL: Yes, the Lexus. You say your Myanmar photographs don’t have the same “attraction” as your earlier projects, meaning they’re not as driven by aesthetic considerations?

PCL: No, I’m less concerned about photographic aesthetics. My work is evolving into something else. The people’s stories are more important. I try to help people when I can. Recently I helped a poor twenty-five-year-old Taishan Chinese girl move to Canada. I chose not to use my camera to document her, so that I could sense things differently. I’m shifting my priority from seeing like a camera to trying to make a difference in improving people’s lives. I want to give more than take.

AL: Would you say that when you do use the camera, your new photography is in keeping with what you see as the character of today’s diaspora?

PCL: The internal diaspora is different today, because corrupt government officials and developers are forcing the villagers to move and there is no home to return to. Folks are uprooted, and it’s a forced migration. Hoodlums are hired to force the people out. They burn down houses and destroy the villages. Villagers in the cities complain about how they’re being treated, but no one really listens. It’s a bad situation. Web citizens have begun to expose the evils, and some in the government are trying to address them.

Outside China, I would say that not wanting to return to China to live is more a feature of today’s diaspora. It’s just hard to live in such a competitive and abrasive society where people tend to be uptight and quite calculating. Being ordinary citizens in a land outside China is okay. Life is easier abroad. And the one-child policy in China changed the way “family” is viewed. In the worst cases, the children are spoiled but lonely. They don’t take care of each other, and oh man, they don’t send money home.

AL: Would you return to China to live?

PCL: I can weasel my way in and out of every part of China, but I have no desire to live there. It’s difficult to survive in China every day, and I don’t trust the food and the environment is so degraded. I’d lose five years of life with clogged arteries!

AL: And Nepal?

SL: No, I don’t think so. It’s mostly because of my career. I want to be an artist and want to exhibit my work internationally. Being based in Nepal would make that a little difficult.

AL: And Singapore?

WLT: I’d like to return to Singapore to live for a short period, but it would be difficult for my partner to find a job in Singapore. Such is life.

Fig. 13. Wei Leng Tay, Kirk and Karen, Hong Kong, 2013, from Hong Kong Living, courtesy the photographer.

Fig. 13. Wei Leng Tay, Kirk and Karen, Hong Kong, 2013, from Hong Kong Living, courtesy the photographer. Born in 1950 in Hong Kong, Pok Chi Lau is an Emeritus Professor at the University of Kansas. To discover new aspects of contemporary Chinese migration, he travels in distant lands and fishes in deeper waters more than ever.

Surendra Lawoti is a Nepal-born, Toronto-based photographer interested in human circumstances and their recognition. His current project, This Country is Yours, focuses on activists of six social and political movements, including indigenous nationalities, women and Dalits during Nepal’s historic constitution writing process.

Wei Leng Tay is an artist. Her work is currently being exhibited in The Roving Eye: Contemporary Art from South East Asia, at ARTER Space for Art, Istanbul, until Jan. 4, 2015, and Out of Place, at Lumenvisum, Hong Kong, until Nov. 23.

Anthony W. Lee is the Idella Plimpton Kendall Professor of Art History at Mount Holyoke College and guest editor of this issue of the TAP Review.