We’ll Take Your Artifacts but Not Your People: The Komagata Maru in Canada’s South Asian Diasporic History

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In 1914, Canada founded its monument to world culture, the Royal Ontario Museum, in which artworks from India formed a part of its growing Asian collections. That same year a ship full of people from the British colony of India were turned away at Vancouver’s port. “We’ll take your artifacts but not your people”: a hundred years ago, this seemed to be the message that went out across the Dominion of Canada.

In 2014, on their centennial anniversaries, there have been many events celebrating the museum and commemorating what has been termed “the Komagata Maru incident.” On the one hand, the passage of time traces how far Canada has come in embracing its multicultural population as a core of its national identity. On the other hand, that same passage of time demonstrates how fraught with tension this sense of nationalism continues to be. In this essay, I focus on the Komagata Maru incident.

I have been struck by how the photographic archive has been galvanized as a way to represent this event, and indeed has come to define its visual dimensions. I have also been struck by the limits of this archive, and the realization that it can never show what it is purported to show. I will explore how the photograph renders invisible certain dimensions of history because of the diasporic conditions under which it was made.

The Komagata Maru incident refers to what happened starting on May 23, 2014, when a Japanese steamship called the Komagata Maru arrived at Burrard Inlet, near Vancouver, British Columbia. It was carrying three hundred seventy-six passengers, only twenty-four of whom were admitted to Canada; the remainder were detained on board.[1] During the two months that the ship sat in the harbor, the situation was debated in the press and in the halls of government, and became a touchstone for issues both domestic and transnational. One of these issues was Canada’s immigration policy; overlapping it was the relationship between Canada and the rest of the British Empire.

In 1914, Canada was a union of three North American colonies still nominally part of the British Empire but with increasing autonomy.[2] One component of that autonomy was to determine what a new Canada would look like and then shape it through government regulations. At a time of massive immigration by Europeans, the 1908 Continuous Journey regulation was meant to curtail immigration from South Asia.[3] It prohibited the entry of people who did not travel from their country of birth by way of a “continuous” journey. Because of its distance, travel from India required a stopover along the way. The Komagata Maru had made port in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Yokohama. Most of its passengers were from the Punjab: three hundred and forty Sikh, twenty-four Muslims, and twelve Hindu. Many Punjabis had come to Canada at the end of the nineteenth century.[4] Their welcome seemed to come to an end, however, with the increase in immigrants from other parts of Asia, which precipitated fears about fewer jobs and a non-white majority.

In 1914, there were also the expectations of the immigrants. As British subjects, those on the Komagata Maru fully expected to be able to live anywhere within the British Empire, and some wanted to join family who had already settled in Canada. After all, they belonged to a British colony, had served in the British army, and believed that an English education would elevate them to a status equal to that of any other British subjects. It was becoming increasingly obvious, though, that Indians were seen as second-class citizens. This led to a growing dissatisfaction over immigration limits across the British Empire and unequal treatment of particular British colonial subjects. One result was the formation, in 1913, of the Ghadar Party, an organization of Punjabi Indians in the United States and Canada who supported India’s independence from British rule. The voyage of the Komagata Maru was arranged by a well-to-do, Singapore-based fisherman, Gurdit Singh Sandhu, who was a backer of the Ghadar Party. For him, the voyage was an act of resistance, an open challenge to Canada’s racist immigration policies. For this reason, the ship’s arrival was anticipated with great anxiety in the Canadian press.

At the same time, the political act of the voyage was as much about British India as it was about Canada. The passengers saw Canada as part of the British Empire and understood that an incident in one part of the empire could have consequences for another. If they were not allowed to land, Sandhu claimed, Indians in Canada would follow the ship back and start a rebellion.

After two months in the Vancouver harbor, the ship was ordered to leave. It departed on July 23 and reached Calcutta on September 27. News of the ship’s imminent arrival had preceded it, and upon landing it was met by British police, who saw the passengers as political agitators and sought to arrest them. A fight broke out when a few resisted, and nineteen passengers were killed in an event now known as the Budge Budge Riot.

The Komagata Maru incident, then, is a story about a diaspora that never happened. As such, it shows that diasporic history can be not only about movement between two places, but also about the inability to move and about being stuck in between.

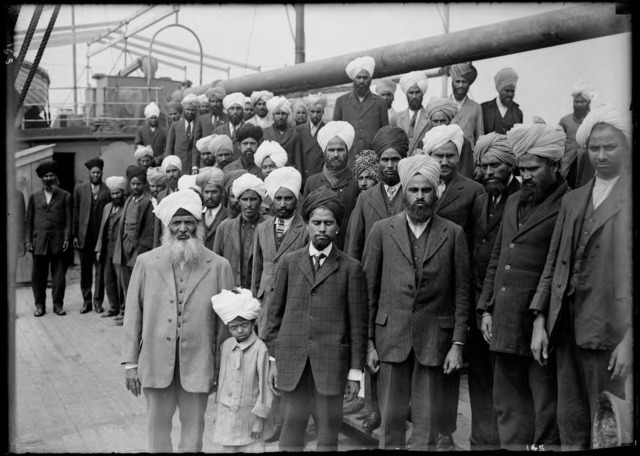

Photographs of the Komagata Maru are characterized by sameness. The majority show the boat sitting in the harbor. Another series of images focuses on customs officials, officers, journalists, and politicians who visited the ship and its passengers. But one image stands out from the rest. It is a photograph of the passengers themselves, standing as a group on board the ship. They wear dark suits and light-colored turbans, as if in a uniform of sorts. At the far left of the group is Gurdit Singh Sandhu, with his graying beard, dressed differently from the other men in a light-colored suit, perhaps as a deliberate visual strategy to highlight him as the leader. Next to him is the youngest member of the group, a boy whose ill-fitting turban and tilt of the head make him seem to lean toward Sandhu as if to a protective father figure.

Fig. 1. Leonard Frank, Sikh Men and Boy Onboard the Komagata Maru, May 23 to July 23, 1914, Leonard Frank collection, Vancouver Public Library (photo 6231).More photographs by Frank of the Komagata Maru incident viewable on the Vancouver Public Library website (http://www.vpl.ca/frank/index.html) or Flickr Commons (https://www.flickr.com/photos/99915476@N04/sets/72157638424729844/).

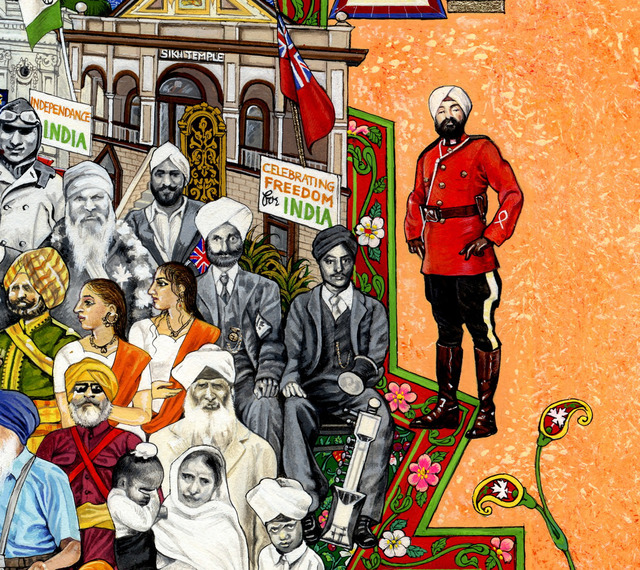

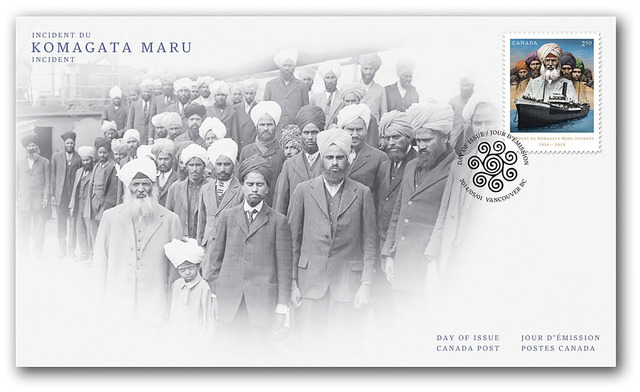

Fig. 1. Leonard Frank, Sikh Men and Boy Onboard the Komagata Maru, May 23 to July 23, 1914, Leonard Frank collection, Vancouver Public Library (photo 6231).More photographs by Frank of the Komagata Maru incident viewable on the Vancouver Public Library website (http://www.vpl.ca/frank/index.html) or Flickr Commons (https://www.flickr.com/photos/99915476@N04/sets/72157638424729844/). This photograph has been reproduced widely in activities that commemorate the Komagata Maru incident.[5] For example, it is featured in Ali Kazimi’s documentary film “Continuous Journey” (2004), and his subsequent book Undesirables: White Canada and the Komagata Maru - An Illustrated History (2012).[6] A detail of Gurdit Singh and the young boy is in a painting by The Singh Twins commissioned by the Royal Ontario Museum on the Sikh Diaspora in Canada. Most recently, it served as one of the two official first-day covers for a commemorative Komagata Maru stamp issued by Canada Post.

Fig. 2. The Singh Twins, detail from Sikhs in Canada, watercolour on board, copyright The Singh Twins: www.singhtwins.co.uk, 2010, Royal Ontario Museum Collection 2010.53.1, Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust Fund.The whole painting can be viewed on the ROM Blog (http://www.rom.on.ca/en/blog/collection-highlight-sikhs-in-canada) and a video of The Singh Twins discussing this work can be seen on YouTube (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vC82Z2oTO9Y).

Fig. 2. The Singh Twins, detail from Sikhs in Canada, watercolour on board, copyright The Singh Twins: www.singhtwins.co.uk, 2010, Royal Ontario Museum Collection 2010.53.1, Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust Fund.The whole painting can be viewed on the ROM Blog (http://www.rom.on.ca/en/blog/collection-highlight-sikhs-in-canada) and a video of The Singh Twins discussing this work can be seen on YouTube (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vC82Z2oTO9Y).  Fig. 3. Komagata Maru: official first-day cover — passenger photo, 19.1 x 11.3 cm., copyright Canada Post Corporation (2014), issued 11 April 2014, designed by Paprika, Montreal.

Fig. 3. Komagata Maru: official first-day cover — passenger photo, 19.1 x 11.3 cm., copyright Canada Post Corporation (2014), issued 11 April 2014, designed by Paprika, Montreal. In some ways, the focus on this photograph is understandable. I have found no other image that portrays so intimately the passengers aboard the ship. Whereas other photos are taken from the dock, this image is produced by a camera that is on board, a short distance from passengers as they look in its direction. The photograph imparts a connection between the people and the viewer, and conveys a sense of their agency. The men seem to be representative of a group, of a diasporic community in India trying to come to Canada linked to one already in Canada and struggling to claim the right to belong. They seem steadfast in their convictions and willing to face enormous risks. For many viewers, especially those in the South Asian diaspora today, this photograph has profound emotional impact.

And yet the image was produced out of a business relationship between the photographer and the government agency that hired him. Indeed, most of the images from the Komagata Maru incident were produced by a single photographer: Leonard Frank. Born in Germany in 1870, Frank moved to San Francisco in 1892 and then, two years later, to Vancouver in search of gold. Less than successful in that effort, he began to take pictures (his father was a photographer in Germany) with a camera he had won in a raffle. He took more than fifty thousand photographs documenting the history of British Columbia between the wars. He was often commissioned by the provincial and federal governments and became the official photographer for the Vancouver Board of Trade.[7]

The Komagata Maru must have been one of his earlier commissions. Based on surviving dated photographs, he seems to have photographed it on two occasions: once while it sat in the harbor and he went on board and a second time, in July 1914, at its departure. No other photographer’s work provides so intimate a portrait of the passengers because of the access he enjoyed through his association with the Canadian government.

At a quick glance, the image appears to be an ill-composed scene of a lopsided group with a gaping spot at the left. But considering the circumstances of its making, we must regard it as a carefully composed scene. The men are wearing their best Western suits, have carefully tied their turbans around their heads, and gaze deliberately toward the camera. Perhaps the idea had been to take the picture with the camera positioned ninety degrees to the left, which would have put Gurdit Singh Sandhu in the center of the group. But Frank might have recognized that the composition would have eliminated much of the ship, thus erasing any sense of context, crucial in this case to give the image its semiotic power. Thus, Frank may have asked the men to turn and then repositioned the camera so that Gurdit Singh was on the left, which left space for a bit of the ship’s deck and other components to be visible. In this way, the ship was included as a member of the group portrait.

It is ironic that the very photograph produced out of the disciplinary mechanism of border regulations and customs requirements would be the one used decades later to gain whatever access is possible to the people on board the ship and to raise awareness about the event. But irony is, in fact, the point. It illuminates the unstable nature of the photograph and how its meaning is determined more by how it is used than by its inherent visual qualities or the conditions of its making. Through its use today, one can say that the image has been removed or reclaimed from the disciplinary context in which it was created and reinvented into an image that empowers a community in the present.

For me, though, there is another point to consider: the nature of the archive itself and the impossibility of making certain aspects of diasporic history visible. This kind of diasporic image points to an absence attached to any photographic archive. The seductive nature of the photographic image, and by extension the archive — with its epistemological status connected to reality — obscures the subjects and subjectivities not recorded. And while this may be true with most photographs, I would argue there is particular applicability to diasporic history. Within the diasporic indexical image lies all that it does not index. The diasporic photograph is a witness to that which can never be recovered. The centrality of images made as a result of exclusionary practices demonstrates that there is always already a limitation to the representational choices. There will be things that can never be represented, that can never be accessed. For the Komagata Maru, there will always be an inability to access the experiences of passengers, however much archive projects and memorials rage against that. The photographs make the event visible in one way, but they render the event invisible in more ways.

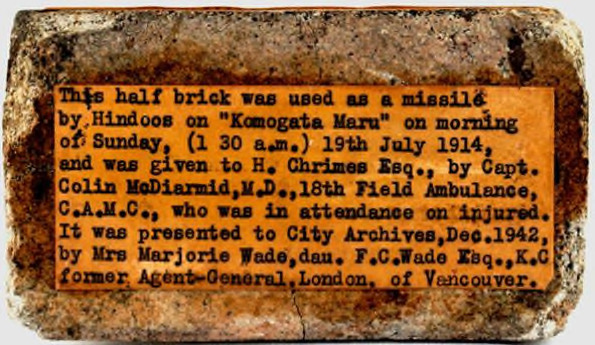

The relationship between the founding of a museum and the history of immigration may not immediately manifest itself, but there is, indeed, a relationship, in how a new nation conceives itself. The movement of peoples and the collection of artifacts are linked through the histories of colonialism and empire and by the subsequent self-fashioning of nations vis-à-vis their cultural institutions and multicultural communities. In the absence of historical records, artifacts can take on meaning, indexing events just as do photographs. For the would-be immigrants on the Komagata Maru, a brick one of them threw preserves a sense of agency on their behalf that little else in the archive achieves. Just like the sunlight bouncing off the passengers’ bodies and entering the camera’s lens to sensitize the photographic surface, the brick is a direct connection to the hand of one of the passengers and his decision to hurl it through space. Both have affective power for communities today because of their direct physical connection to the people on the ship. This is an important aspect of recent projects that have produced real change in public awareness about the Komagata Maru and have garnered political and moral capital for Canada’s South Asian community. And yet the brick, like the photograph, will always be bound by the circumstances of its collecting. That it survives at all is because it was kept as souvenir of the criminal nature of the boat passengers, as an old label on the brick indicates.[8] For each brick and photograph that survives, how much does not because it didn’t fit within the framework of immigration and the mechanisms of customs control?

Fig. 4. Brick thrown by passengers on the Komagata Maru, Museum of Vancouver Collection H982.217.104.

Fig. 4. Brick thrown by passengers on the Komagata Maru, Museum of Vancouver Collection H982.217.104. The diasporic photograph is one that draws attention to absence more than presence, to invisibility more than understanding. This doesn’t mean that diasporic histories cannot be viewed, but we must pay close attention to what the photographic record seems to reveal and what it actually does, and what is not recorded at all.

Deepali Dewan is Senior Curator in the Department of World Cultures at the Royal Ontario Museum and Associate Professor in the Department of Art at the University of Toronto. She is the author of Embellished Reality: Indian Painted Photographs (2012) and co-author (with Deborah Hutton) of Raja Deen Dayal: Artist-Photographer in 19th-century India (2013).

Notes

Details about the Komagata Maru incident can be found from a variety of sources. I have chosen to use http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Komagata_Maru_incident (accessed 22 February 2014) and http://komagatamarujourney.ca/, a website created by Simon Fraser University Library

The final vestiges of legal dependence were not severed until the Canada Act of 1982.

The Continuous Journey Act was one among a series of immigration regulations passed by the Canadian Government stretching back to the 1880s.

People from Punjab had started settling in Canada in the 1890s, particularly as retired servicemen connected to the British military. They worked in Canada’s west-coast lumber industry and established farms. By 1910, due to the influx of a large number of immigrants from Asia, particularly China and Japan, Canada passed The Immigration Act.

From the 1980s onward, the Komagata Maru incident gained attention through the increased efforts of Canada’s South Asian, particularly Sikh, community to gain greater visibility and representation within Canada’s growing multicultural environment. It received a renewed push in 2008 when the Canadian federal government formally apologized for the Komagata Maru incident and set up a $2.5 million fund to support projects from the Indo-Canadian community to commemorate it. This led to an online archive to preserve documents and oral histories hosted by Simon Fraser University and funded by the Department of Citizenship and Immigration Canada under the auspices of the Community Historical Recognition Program (CHRP). Most recently, a traveling exhibit was organized by the Sikh Heritage Museum of Canada, an organization founded a few years ago in a Toronto suburb.

Ali Kazimi (Director), “Continuous Journey,” [TV Movie Documentary], Canada, 2004; Ali Kazimi, Undesirables: White Canada and the Komagata Maru – An Illustrated History, Vancouver: Douglas & Mcintyre, 2012.

http://www.vpl.ca/frank/index.html (accessed 22 February 2014). His work is preserved in the Vancouver Public Library.

It has since been donated to the Museum of Vancouver, which has thoughtfully contextualized the brick within its long and complex history.