Going “Native” in an American Borderland: Frank S. Matsura’s Photographic Miscegenation

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

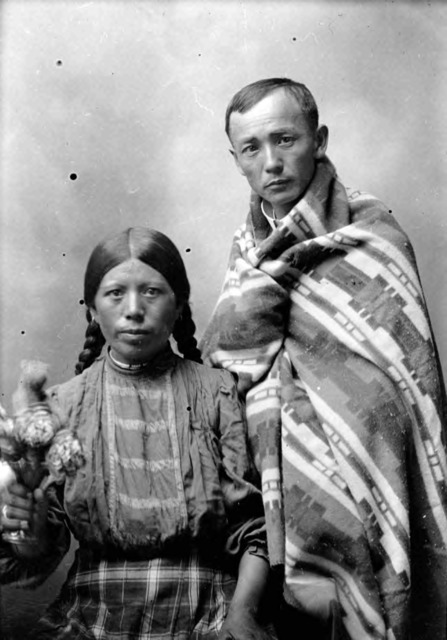

A seated woman and a standing man pose for a studio portrait. Wearing a loose-fitting shirt and a patterned skirt, the woman raises her right hand, which is holding an object that looks blurry because of its movement—indicating the photograph’s long exposure or the camera’s slow shutter speed. Beneath the man’s closely combed hair is a solemn face, with horizontal lines cascading from his forehead and skin sagging below his eyes. He wraps a large blanket around his body, a guarded gesture that contrasts with the woman’s frontal and open pose. There is an implied connection between the two, who share facial features that could be best described, without knowing their race or ethnicity, as “non-Caucasian.” Simultaneously, they engage the camera: her gaze appears direct and determined; his, weary and forlorn.

Fig. 1. Frank Matsura, Matsura and Susan Timento Pose at Studio, ca. 1912. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-99), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.

Fig. 1. Frank Matsura, Matsura and Susan Timento Pose at Studio, ca. 1912. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-99), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries. The title, Matsura and Susan Timento Pose at Studio (ca. 1912), compounds a mystery associated with this photograph. It is attributed to Frank Sakae Matsura (松浦 荣, 1873–1913), which means the man in the picture is the photographer himself. But who is Matsura? What is his relationship to Timento, with whom he poses like a couple in a formal portrait? And what is the symbolism of Matsura, who has a Japanese name, wrapping himself in one of those trade blankets with Native American–inspired textiles?[1]

Neither the portrait nor its photographer was familiar to the curatorial team to which I belonged in 2005.[2] It was thus surprising to discover that this image is only one of more than twenty-five hundred photographs attributed to Matsura, whose extensive oeuvre is divided between collections at the Okanogan Historical Society and Washington State University Pullman. According to the archives, Matsura’s prodigious output occurred between 1907 and his death, at age thirty-nine, in 1913.

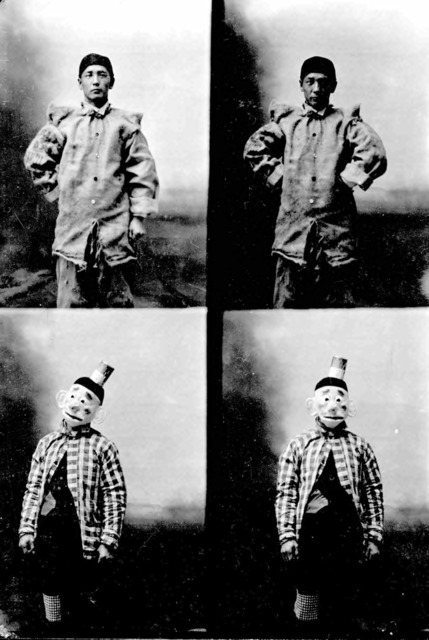

As a chronicler and sought-after photographer in Okanogan, Matsura amassed arguably the most comprehensive records of the region and its residents. But it is his portraiture that most fascinated me, for in addition to producing conventional studies, Matsura consistently pictured himself “play-acting” with his sitters. Particularly striking are the ones in which Matsura, a bachelor in his thirties, poses with his female models as if they are close friends, if not lovers. Matsura’s photographic masquerade—wearing an array of garments, from animal coats, clown costumes, and European-style suits to Indian blankets—points to a sophisticated understanding of photography’s perceived verisimilitude (the appearance of being true or real) and performance (conscious acting for the camera and the imagined viewer). These are critical aspects that photographers have investigated since the medium’s invention, in 1839.[3] Matsura’s “authorial participation” (inserting himself into the imagery) also reminds me of some late-twentieth-century photographers’ work, in which the artists deploy “visual embodiment”—incorporating their own bodies in their picture making—as a strategy to create commentaries on cross-cultural encounters in a globalized world. Artists such as Tseng Kwong Chi (Hong Kong, 1950–1990) and Nikki S. Lee (South Korea, b. 1970), to mention only two, offered photographic interrogations of issues that range from tensions in international geopolitics and the effects of commercial imperialism to visual “passings” that disturb and call into question national, racial, and cultural stereotypes.[4]

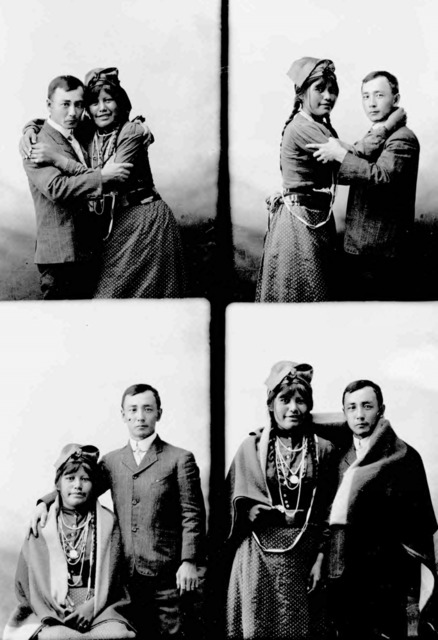

Fig. 2. Frank Matsura, Matsura and Norma Dillabough Studio Portraits, ca. 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-21), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.

Fig. 2. Frank Matsura, Matsura and Norma Dillabough Studio Portraits, ca. 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-21), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.  Fig. 3. Frank Matsura, Matsura in Clown Costumes, ca. 1908. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-02), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.

Fig. 3. Frank Matsura, Matsura in Clown Costumes, ca. 1908. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-02), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries. I propose to consider Matsura’s studio (self-)portraits, such as Matsura and Susan Timento Pose at Studio, to be remarkable precedents to the post-WWII imagery of physical, geographical, and cultural traversals. This enables me to reframe Matsura’s repertoire, which has been presented, by and large, in the existing, albeit scant, literature as the work of a prolific documentarian.[5] Matsura’s portraiture could be considered as a similarly self-conscious photographic investigation of conditions of diaspora, but without the ironic and even confrontational visual rhetoric that the aforementioned artists have presented in their imagery of dislocation, anxieties, and ambiguities. Collectively, Matsura’s pictures represent diverse relationships between the residents of an American “borderland,” a town where everyone was a transplant either by choice, as in homesteaders’ pursuit of economic opportunity, or by political and legislative pressure, as in Native Americans’ forced relocation into reservations. (I use both “borderland” and “frontier” in this essay, with a preference for the former, as it points to the implied tension in the contacts between peoples/cultures/economic-political interests without mythologizing or leaving unquestioned an expansionist impulse embedded in the term “frontier.”) Photography offered Matsura a dynamic tool to engage with the people in a host country that he chose to call home.

This is not to say that Matsura’s work was uncritical, however, as my analysis of the Matsura-Timento portrait will show. Through incorporating his own body, Matsura’s portraiture presents a revealing and unconventional picture of social, racial, and gender crossings in an American borderland town. Read against the backdrop of assimilationist policies that aimed at achieving an institutionalized erasure of difference vis-à-vis Native Americans, Matsura’s pictures of “playing spouse” with both Indian and Caucasian women—“photographic miscegenation,” as I call it—can be understood as his productive means of interrogating sociopolitical issues that had immediate and personal relevance for him and his cohort.

A Mysterious Alien

A biographical sketch helps to establish Matsura’s background and his milieu in Okanogan.[6] It should be noted, however, that what people in town knew about Matsura’s life in Japan came from his own, selective accounts. It appears that Matsura was aware of the fluidity of one’s identity and engaged in a kind of re-presentation of who he was. For example, the writer JoAnn Roe reported that Matsura arrived in Okanogan a cultured and educated man who could speak English with “scarcely an accent.” Yet when strangers came to town and addressed him in Pidgin English, he would play along and respond with “an outrageous flood of broken English,” which was apparently a put-on, if the stranger stayed long enough to discover.[7] In addition, Matsura altered the spelling of his name, from the original “Matsuura” (which transliterates the longer u sound in his last name) to “Matsura,” a change that took place around 1905, a year or so after his photography began to attract attention in local newspapers.[8] Although the deletion of a u seems minor, it is an emblematic act that indicates Matsura’s astute understanding of an immigrant’s self-representation, relevant when reading his photographs, particularly his self-portraits.

In any case, Matsura’s version of the story was that he sailed to the United States in 1901, disembarking in Alaska and traveling on to Seattle, where he found jobs paying meager wages. In 1903 he answered an ad for a handyman at the Elliot Hotel in Conconully, the Okanogan County seat at the time, and became a beloved employee described as hardworking and pleasant. According to Roe’s research, Matsura took pictures when he was off duty and made prints in the hotel’s laundry-room sinks. He also began receiving commissions to photograph the economic development around the county. As early as 1904, Matsura’s name appeared in the local newspaper, The Okanogan Record, and was often accompanied by praise: for example, “We have on our desk a panoramic view of Conconully, the compliments of Mr. Frank Matsuura, which is a very credible piece of work,” and “Frank is one of the most successful amateur photographers in this section.”[9]

With rising demand for his photographic services, Matsura established a studio in Okanogan in 1908 and his business flourished. His popularity is apparent from the attention he received when in 1906, thanks to the generosity of a Japanese relative, he purchased a camera that cost three hundred and fifteen dollars. The Okanogan Record commemorated the occasion: “It is an instrument of which anyone might feel proud. Now we may look for even better views than ever of our beautiful surrounding scenery.”[10] The pronouncement attests to Matsura’s status in the community, but it also provides a clue to his background that distinguishes him from the working-class residents of Okanogan. For a Japanese immigrant to be gifted that amount of money (more than seven thousand dollars in today’s value implies that Matsura’s family had considerable financial means, an indication of his upbringing in a certain social class.

Fig. 4. Frank Matsura, Matsura with Orril Gard and Mathilda Schaller at His Studio and Gallery During the Christmas Rush, 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-95), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.

Fig. 4. Frank Matsura, Matsura with Orril Gard and Mathilda Schaller at His Studio and Gallery During the Christmas Rush, 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-95), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries. What the local residents did not know is that Matsura indeed came from a prominent familial line but experienced tragedies at a young age. Tatsuo Kurihara, a Japanese photographer and devoted biographer, uncovered that Matsura’s lineage could be traced to the Matsuura clan (松浦党), who ruled the Hirado Domain (平戸藩) in the modern-day Nagasaki Prefecture (長崎県). By the time Sakae (Frank) was born, the eldest son of Yasushi Matsuura (松浦 安), in 1873, his family had become part of the Shizoku (士族), the “warrior-families” class that was created to absorb the samurai warriors under the Meiji Restoration as a way to weaken their political influence. Young Sakae lost both parents to illness before he turned nine, and his grandmother, who was his and his sisters’ guardian, died when he was twelve. In 1886 he was sent to live with his uncle Tadashi Okami (岡見 正), his father’s younger brother, who married into the Okami family and took their last name.[11]

As Matsura’s “adopted” father, Okami played an instrumental role in providing young Sakae with the kind of upbringing that would inform his photographic work in Okanogan. Okami was a teacher, a learned man who dabbled in a variety of subjects, among them Sinology, calligraphy, singing, and English.[12] He became a Christian in 1878 and served as an elder at Daimachi Church (台町教會), in Tokyo, where Matsura was baptized in 1888 by a pastor named Kumaji Kimura (木村 熊二; 1845–1927). Kimura, who studied in a seminary in the United States and was ordained by the Classis of New Brunswick of the Reformed Church in 1882, was more than Matsura’s pastor.[13] He was a student of Renjō Shimooka (下岡 蓮杖; 1823–1914), one of the pioneers of photography in Japan. Biographer Kurihara suggests that it was from Kimura that a young and curious Matsura learned English and acquired sufficient technical proficiency to be able to start his photography business in Okanogan.[14]

Most of this background information was withheld from his friends in America. Having left his old life behind and started a new one, Matsura seemed content to cast himself as both a worker and a photographer of the people. And he succeeded in integrating himself into the community, as shown by the response to his sudden death, from hemoptysis, on June 16, 1913. His last moments were recounted in newspapers in a dramatic fashion:

Joe Leader, town marshal at Okanogan, thought he had discovered a burglar in Mr. Neuman’s store, and while he had the place guarded asked Matsura to notify the proprietor. Matsura did not run, according to those who saw him on the way, but he was of an excitable disposition and probably took the matter too seriously. He fell over on Mr. Muldrow’s porch with the remark, “Oh, I am dying.”[15]

An Okanogan Independent story also reported on Matsura’s death, accompanied by an unreserved approbation: “[Matsura] held the highest esteem of all who knew him. He was one of the most popular men in Okanogan,” and “although an unpretentious, unassuming, modest little Jap, Frank’s place in Okanogan city will never be filled.”[16] The “little Jap” was likely a vernacular to signal both Matsura’s small stature and his foreignness, though it still carried a hint of prejudice, for the proper “Japanese” could have been used in print. It is notable, however, that an immigrant’s presence and influence on his host community was so thoroughly recognized.

Indeed, Matsura’s funeral was one of the major events in Okanogan during the summer of 1913. The Okanogan Independent reported that more than three hundred mourners packed Okanogan’s Auditorium, the largest hall in town, for Matsura’s public memorial. In the eulogy, the Reverend Fred J. Hart drew analogies between Matsura’s residency in Okanogan and Saint Joseph’s diaspora in Egypt. Just as Joseph “became one of the truest and most useful of Egyptian citizens and patriots,” he said, Matsura was perceived to be an “excellent citizen” and one of the most “useful men in our community.” And no one else had done as much as Matsura, the minister added, to “advertise Okanogan and vicinity,” referring to his photography. “Frank was a friend to everyone in Okanogan . . . life in our town was brighter and better for his presence.”[17]

The effusive tribute in the Okanogan Independent, timed to appear on Independence Day, could be regarded as a tacit commentary on both Matsura’s full integration and the exclusionary immigration laws that prevented this “useful” member from obtaining a recognized status. The Reverend’s repeated use of the word citizen to describe Matsura, for example, served as an implicit intervention to affirm Matsura’s standing in the community, for it was reported that Matsura lamented that “the laws of the United States would not let him become a citizen. He liked America and it is doubtful he had an enemy in the country.”[18] Whether or not this newspaper quote was the work of a sympathetic writer could not be verified. It nevertheless represented the community’s sentiment toward the loss of an immigrant whom the townspeople had embraced, the writer put it, as one of “their own.”

Portraits of a Diasporic Community

The term “their own” requires qualification. As mentioned, Okanogan consisted of demographically diverse people who moved to the area for a variety of reasons. The 1910 census counted more than 12,500 people living in the 5,211-square-mile county, a region with enough economic activities to be established by the state legislature as Okanogan County in 1888. Among the residents were predominantly white homesteaders, but there were also several groups of Native Americans, such as Okanogan, Colville, San Poil, Moses, and Methow. Whereas the indigenous peoples had lived in the broader Okanogan region and maintained a seminomadic life, President Ulysses S. Grant’s executive orders in 1872 in effect confined the Native communities to live on the Colville Reservation, which occupied the southeastern portion of Okanogan County.[19]

As the historian Murray Morgan points out, by the time Matsura arrived in the Okanogan Valley, in 1903, there were “cows and cowboys, kids and one-room schools, steamboats round the bend, railroads in the offing, and telephone lines looping across the brown hills.”[20] There were also “three main street saloons, two hotels with dining rooms (the Central and the Riverside), and several restaurants.”[21] These became the subjects of Matsura’s pictures. Being the photographer in town, Matsura and his camera were everywhere to capture all aspects of the region’s development, such as the construction of the dam (1910) and the orchards that benefited from the irrigation project. He traveled with surveyers and paid special attention to workers and Indian communities. He also acted as the photojournalist reporting on problems, such as the collapse of a link of Omak’s drawbridge, as well as landmark events: the arrival of the first passenger car of the Great Northern Railroad, for example, and the Centennial Flag Raising at Fort Okanogan in 1911.[22]

The genre in which Matsura produced his most creative and arguably most invested imagery was portraiture. Prominent in his oeuvre, Matsura’s pictures of people, taken in and out of his studio, constituted his source of income. People flocked to Matsura’s studio for formal portraits, judging by the hundreds of photographs produced between 1908 and 1913. Parents brought their children, men and women posed with their lovers or friends, and sports teams and professional organizations sat for group pictures.[23] Matsura’s portraits would become revealing representations that enable us, more than a century later, to see the faces of settlers and migrant workers of various ethnic backgrounds, those who were often rendered anonymous in the broader narratives of history.

The large number of clients who used Matsura’s photographic service illustrates a sustained fascination with photography since its invention. Eighty years later, in a small town in Washington, people gladly took advantage of the improved technology, such as shorter exposure time and greater film sensitivity, and had their likenesses captured for posterity. As the late scholar and photographer Allan Sekula has elucidated, the photographic portrait “extends, accelerates, popularizes, and degrades” the traditional function that painted portraiture since the seventeenth century had assumed: as the “ceremonial presentation of the bourgeois self.”[24] As painted portraiture was prohibitively expensive for the working class, it had been the wealthy—the aristocracy and royalty—who could afford to hire painters to create ceremonial or “honorific” (Sekula’s term) imagery of themselves for both private and public consumption. Photography diminished and removed painted portraiture’s exclusivity because the proliferation of image-making tools helped create a more level playing field, at least as far as the accessibility to portraiture is concerned.

Sekula also points out, though, that photography is always “paradoxical” as a “system of representation capable of functioning both honorifically and repressively,” a “double operation” that is most apparent in photographic portraiture. As machine-produced imagery, photographs were believed to be “true” and “objective,” although these notions were challenged by its practitioners as early as the time of the medium’s inception.[25] Bolstered by the belief in its supposed verisimilitude, photography served not only the commemorative (“honorific”) functions for the bourgeois, but also as the preferred instrument for biological, medical, ethnographic, and other studies and documentation. Implicit in such ostensibly “objective” photography was an impulse to make visible the difference (physical, cultural, spiritual, and so on) between European imperialists (early adopters of state-sponsored photographic surveys of colonies, for example) and everyone who did not look or act like them, or the Other.

Photography’s role, in this context, was to “define both the generalized look—the typology—and the contingent instance of deviance and social pathology,” as Sekula writes.[26] In other words, photography contributed to establishing paradigms in which pictures were used to show, substantiate, and support judgment of normality (mainstream) or abnormality (deviation) in terms of physiognomy, behavior, and various social and cultural customs and practices. Photographs of criminals, patients with physical or mental diseases, dissenters and rebels (within and outside of colonial powers), and foreigners and immigrants offered visual contrasts to the bourgeois order that those in power worked to uphold. “Every proper portrait has its lurking, objectifying inverse in the files of the police,” Sekula reminds us, and the photographic portrait has always been a “socially ameliorative as well as socially repressive instrument.”[27]

Considering Matsura’s portraits in this framework gives us a more nuanced reading of his Native American portraiture beyond treating the pictures as mechanical reproductions by a documentarian or commercial photographer. The “double operation” of portraiture is further complicated in Matsura’s case because of his dual role as the maker and the subject. Understanding photographic portraiture’s “paradoxical” nature enables us to consider Matsura’s photography as a critical means through which differences were negotiated and broader issues investigated, among them notions of belonging and community, paradigms of gender relations, and policies concerning “the Other,” such as Native Americans and aliens like him.

Matsura was trusted in the Indian communities. They let him photograph them on the reservations and also traveled to his studio to commission formal portraits. For both types of pictures, they dressed to the nines to ensure that they were represented in the best light. Among many of Matsura’s elaborately dressed sitters was Chiliwhist Jim, in a 1910 studio portrait. According to Washington State University’s archival description, Jim (La-ka-kin), a Methow Indian from Malott (nine miles to the southwest of the city of Okanogan), was a medicine man and prosperous rancher. All his identifiers were on display: feathers, concentric necklaces, embroidered vest and pants, beaded moccasins. Holding an upright pose, Jim looks proud and statuesque, and is framed by the aura in the backdrop that simultaneously foregrounds his face and imbues him with a sense of dignity. Jim’s pose is reminiscent of a 1901 portrait of the legendary Chief Joseph of Nimi’ipuu (Nez Perce), taken by another photographer with extensive Native American portfolios, Major Lee Moorhouse (1850–1926).[28] But unlike Moorhouse’s imposing, full-body shot of Chief Joseph, Matsura’s portrait is more intimate, implied by the closeness of the camera to his sitter and the lens’s position, set at about the same height as the seated Jim.

Fig. 5. Frank Matsura, Chiliwhist Jim, ca. 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-14-09), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.

Fig. 5. Frank Matsura, Chiliwhist Jim, ca. 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-14-09), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.  Fig. 6. Lee Moorhouse, Nez Perce Chief Joseph poses in blanket outdoors, 1901. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, NA 605.

Fig. 6. Lee Moorhouse, Nez Perce Chief Joseph poses in blanket outdoors, 1901. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, NA 605. It is Matsura’s Native American imagery that the scholar Glen Mimura focuses on in an essay, a recent and critical analysis of Matsura’s photography. Mimura proposes that Matsura’s pictures of local Native peoples offer far more complex depictions of “a frontier society in transition” than the “uniform pronouncement on the ‘death’ of the frontier and its Native peoples” exemplified by the photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis’s project (and I would include Moorhouse’s), which perpetuated the myth of Native Americans’ “irreversible process of cultural and biological extinction.”[29]

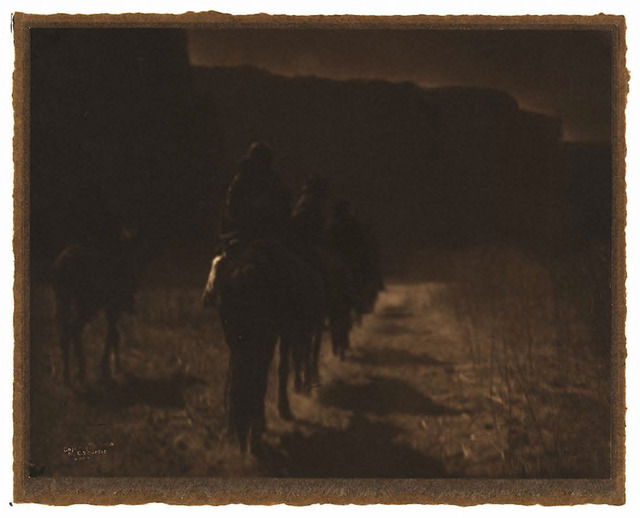

The project to which Mimura refers is The North American Indian (1907–1930), by Curtis (1868–1952), a twenty-volume publication that contains pictures of Native Americans from more than eighty tribes.[30] The “vanishing race” subtext was visualized in his much-reproduced image The Vanishing Race-Navaho. The anonymous figures are taken by horses on a dimly lit path toward a horizon where the ominous gloom awaits. Undulating lines render the picture lyrical and dreamlike. Coupled with the soft focus and saturated brown ink used in photogravure printing, the photograph is a skillfully crafted epitome of melancholy—one that no doubt Curtis was proud of, as he used it as the first picture of his ambitious series.[31] It is also an image that drives home the view shared by many of his contemporaries that he and his camera were doomed to be the last witness to the extinction of American Indians.

Fig. 7. Edward S. Curtis, Vanishing Race - Navaho, 1904. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004672871/.

Fig. 7. Edward S. Curtis, Vanishing Race - Navaho, 1904. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004672871/. Mimura’s thesis is that Curtis was a major contributor to the “melancholic vision of a mythic American West.” Matsura’s work, on the other hand, “implies no such epistemological conceit: the photographer and his subjects evidently share the same world; walk the same streets, fields, and riverbanks; live in the same historical time.”[32] In other words, Matsura’s photography presents to the viewer, then and now, varied aspects of the real and living Native peoples in Okanogan. Collectively, these pictures demonstrate their “extraordinary versatility in adapting to the new, difficult historical circumstances,” as they are shown to have lived and even thrived in a “respectful if uneven, ambivalent coexistence.”[33] As the Native American writer and curator Rayna Green also points out, “What [Matsura] shows of Indians . . . what he shows of this frontier world, is not deviance and heartbreak and isolation. . . . His images of Indian ranchers and cowboys alone give us a better sense of what and who Indians were during those awful years after reservationization.”[34]

Mimura further argues that Matsura’s approach was informed by his identification with Native peoples, for he was “keenly aware, and time and again made aware, of his peculiar, contradictory status as local and outsider: an outsider who, however beloved, could not become local in quite the same way as white settlers due to his racialization.”[35] As a Japanese alien, Matsura did not seem interested in perpetuating the mythologized vision of the frontier as either a “one-way street of Manifest Destiny” or “the unilateral proving ground of white American manhood.”[36] Instead, he presented a “multivalent space constituted by the uneven, overlapping histories of indigenous adaptation and white settlement.” Matsura’s camera “vibrantly documented an alternative vision of this corner of the American West that continues to unsettle the national imaginary.”[37]

A Photographic Borderland

What, then, was Matsura’s alternative narrative? Other than going against the prevalent “vanishing race” plot, how was Matsura’s “American story” told in visual terms? I suggest that Matsura’s ambivalent (local/outsider) position, as Mimura rightly characterizes it, enabled the photographer to experience and represent an American borderland from a perspective different from that of other photographers. This difference is evident in his portraits that make room for nonnormative expressions and behaviors to be performed for the camera. Within the safe confines of his studio, Matsura and his sitters collaborated on using photography to articulate their friendships in visual terms, generate shared diasporic experiences, and develop a sense of place (home), all the while allowing differences to manifest and coexist.

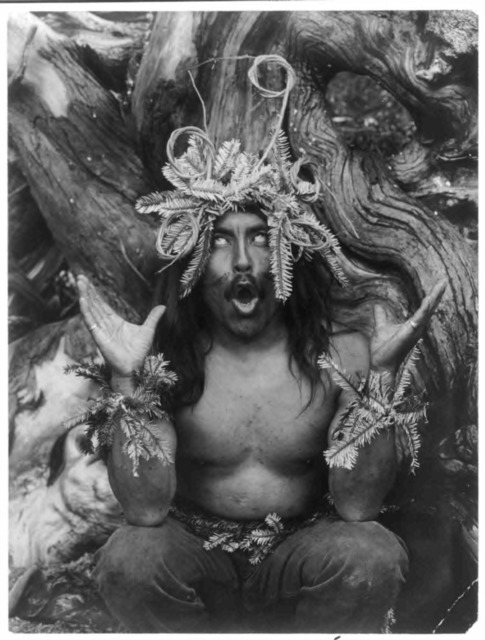

One crucial difference in Matsura’s strategy of portraying Native American is that he seemed to foreground the agency of his models. He achieved this by grounding his work in a give-and-take collaboration: More than being passive clients instructed to pose, his sitters appear to have been invited to participate in Matsura’s picture making. We do not see portrayals of Native Americans in a highly dramatic or stylized fashion, such as Curtis’s seemingly “possessed” Hamat’sa shaman and Moorhouse’s image of a bare-breasted Indian woman that emulates European paintings of female nudes.[38] These serve as visual types that reinforce the pictorial depictions of Native Americans’ different or “exotic” customs as perceived by the mainstream viewers. Matsura’s models were participants who stepped onto his photographic stage understanding that he would respect their representational choices.

Fig. 8. Edward S. Curtis, Hamat’sa Emerging from the Woods — Koskimo, ca. 1914. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003652758/.

Fig. 8. Edward S. Curtis, Hamat’sa Emerging from the Woods — Koskimo, ca. 1914. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003652758/. As Rayna Green points out, “[W]hen Indians wore ceremonial and traditional clothing, it was theirs, not something fancy and inappropriate that Matsura had dragged up out of his trunk for the photographic moment.”[39] Their trust was helped, in part, by the minority status they shared with Matsura. But perhaps more important, the trust was established by seeing Matsura’s willingness to show them “not only in their tribal dress (which he said they voluntarily wore to his studio), but also while wearing workclothes [sic].”[40] His pictures captured the diversity and changes occurring in the local Indian communities—the kinds of visual representations that his Native American models appreciated and collaborated with him to produce.

What also distinguishes Matsura’s work is that he incorporates himself into the portraits. The presence of the photographer is only implied in Curtis’s and Moorhouse’s pictures. Thus, both men’s visible absence allows the pictures to be read as naturalized imagery: we take them as “realistic” portrayals of the figures without the interference of seeing their Caucasian photographers and subsequently considering the uneven power relations between those behind the camera and those in front of it.[41]

In Matsura and Susan Timento Pose at Studio, on the other hand, Timento appears to be as much a partner in posing for a portrait as is Matsura, for she comfortably occupies an equal amount of the space within the picture. It suggests her anticipation of Matsura’s entry into the frame and premeditation on Matsura’s part in composing the image. In addition, Matsura and his models “address” the imagined viewer with their gaze in this and in many other portraits. That pronounced awareness of the camera enables us to read Matsura’s portraiture as (conscious) performance that takes place both in front of and behind the camera. This “authorial participation” demonstrates Matsura’s astute grasp and exploration of the tensions within photography’s assumed verisimilitude and performativity.

The photographic performance is prevalent in other photographs of Matsura and friends, especially the multiple exposures in stamp and postcard sizes. In one photo session, for example, Matsura and Norma Dillabough, whose parents owned the Elliot Hotel (where Matsura was a handyman), run through a gamut of expressions that seem to portray them as young lovers: they embrace, play, and even fight (see figure 2). The quartet of images in the upper-right corner represent a play on opposites and reversals, as Matsura and Dillabough not only switch sides but also swap roles as the active/dominant figure in the pictures. Throughout the twenty photographs in this set, they role-play and perform for the camera variations of a (faux) couple’s dynamic interactions that seemingly conclude with a shot of them coyly shielding their kiss from the imagined viewer’s—and society’s—prying eyes.

These photographs belie the kind of social decorum that respectable women and men had to follow for their public behaviors. Matsura’s physical interactions with his female sitters would not have been appropriate to display elsewhere, and he was known as a gentleman who was “circumspect in his relationships with women.”[42] Although he was said to request that his female sitters have a chaperone when entering his studio, the photographs nevertheless indicate that within the confines of his studio, social norms could be suspended. One assumes that Matsura’s sitters understood photography’s permanence and perceived “truth,” yet they still participated in extensive and carefree photographic play-acting that the public might not approve of. Their participation and trust, as shown in the portraits, thus suggest that Matsura’s studio was considered to be a safe space that was dissociated from, if only momentarily, the regulatory paradigm of the social norm. It could be argued that Matsura’s studio served as a kind of photographic borderland (the fringe), demarcated by Matsura and friends, in a borderland town.

As such, one could also argue that Matsura’s studio portraits take on a transgressive quality, albeit inadvertently perhaps, for within the pictorial construct, a level playing field for different genders and races was created, in addition to the “momentary class transgression” that Harpster rightly describes in her thesis. One sees fluid male-female/dominant-submissive relations, performed for the camera, that defy social expectations or rules. Furthermore, by participating in the pictorial role-playing himself, Matsura disturbs the conventional power relationships between the photographer (in control) and the subject (in submission). He, as a picture maker who is also a minority/émigré, has implied dominance over his photographic subjects of both whites and nonwhites—a reversal of the Caucasian frontier photographer/minority subject power paradigm. But by stepping in front of the camera himself, he complicates the picture of a place where whites and nonwhites appear to live, and play, equally and happily together.

Going Native American

Matsura’s pictures are critical, too, in that they go against the dominant race narratives concerning visual representations of Native communities. One sees indications of his rapport with Native Americans in various candid shots. In one set of stamp-photos, Matsura poses with Miss Cecil Jim, a Methow Indian also known as Cecil Chiliwhist, and a group of young men. Miss Jim appears in three photographs with Matsura, who sits snugly next to her. She poses with another young man displaying body language that suggests a comfortable rapport between them, including her sitting on his lap. In a separate set of photographs, Matura and Miss Jim are in varying states of embrace. Although their outfits and faces highlight their differences, their bodies are closely connected. The last picture, in which they share a blanket in a gesture of friendship and intimacy, illustrates the special bond between an American Indian and a Japanese immigrant, in a borderland where they are both a minority, and simultaneously native and alien.

Fig. 9. Frank Matsura, Matsura, Cecil Jim, and Young Men Pose for Portraits at Matsura’s Studio, ca. 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-19-69), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.

Fig. 9. Frank Matsura, Matsura, Cecil Jim, and Young Men Pose for Portraits at Matsura’s Studio, ca. 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-19-69), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries.  Fig. 10. Frank Matsura, Matsura and Miss Cecil Chiliwhist, ca. 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-05), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington tate University Libraries.

Fig. 10. Frank Matsura, Matsura and Miss Cecil Chiliwhist, ca. 1910. Frank Matsura Photographs (35-01-05), Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington tate University Libraries. The blanket brings us back to the portrait of Matsura and Timento, Cecil Jim’s aunt.[43] Here the blanket is not shared but rather wrapped around Matsura’s body. Different from other lighthearted, candid shots, this looks like a formal portrait with gravitas. That seriousness implies a degree of intentionality in Matsura’s representation of a seemingly interracial “couple,” and points to more critical issues that the photographer perhaps wanted to interrogate through this portrait. It also foregrounds Matsura’s sophisticated understanding and deployment of photography as a productive medium to engage broader, sociopolitical questions in his host country.

First, the image calls attention to the vexed history and symbolism of the blanket. It should be considered as more than a random prop in Matsura’s studio because of the way he deliberately incorporates it into constructing this picture, and because it does not appear in his portraiture as frequently as do the recurring flat cap and the bowler hat. The blanket most likely came from one of the two woolen mills—Pendleton and Racine—that manufactured “trade blankets,” as they are known.[44] The blankets feature designs inspired by Native American textiles, but they were produced by non-Native companies and sold to Indian traders from whom various tribes would purchase the blankets. Native American communities eventually embraced and incorporated trade blankets into their lives and cultures. In fact, the blanket, or “robe,” came to represent “a standard of exchange, a measure of wealth and standing, even a medium to express emotion and meaning”—see Chief Joseph’s portrait in figure 6, for example. To own, cherish, or gift a blanket became a vital part of Native American cultures, for the blanket/robe is omnipresent in a person’s important life events.[45]

The blanket also took on a negative symbolism, however, construed by assimilationists to be a signifier of Native Americans’ perceived resistance to becoming “integrated” or “productive” members of society. Blanket-wearing was speciously equated with a person’s lack of motivation to earn a living because of a perceived “reliance” on the government’s allocation of Indian reservations. Removing the blanket went hand in hand (symbolically) with the U.S. government’s “Americanization” policies, among them using land-allotment negotiations to encourage (and coerce) Native Americans to become U.S. citizens, which would lead to their giving up tribal self-government and institutions.[46]

A major component of the “Americanization” project was the education of the younger Native population. It was during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that boarding schools for Indian children began to proliferate throughout the country, with help from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Numbered at around one hundred and fifty by 1900, the majority of the schools used an assimilationist approach modeled on the U.S. Training and Industrial School, founded by Capt. Richard H. Pratt, in 1879, at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. Pratt was known for his infamous “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” proclamation, which is misquoted as “kill the Indian, save the man.” But in his speech from which the quote derives, he was actually advocating an approach of “citizenizing and absorbing” Indians in order to help them become integrated, “industrious and self-motivating” members of America.[47] Although this helps explain that “kill the Indian in him” meant erasing any “Indian-ness” one may have, his proposal was highly problematic.

Speaking like a true colonialist, Pratt at one point claimed that although slavery was “horrible,” there was a silver lining (“the greatest blessing that ever came to the Negro race,” in his words), for it “saved” seven million Africans from living among their “fellow savages” and allowed them to live in a “free and enlightened America.”[48] Underlying Pratt’s justification for slavery was a fallacious view of Africans as commodities whose “value” had been improved thanks to being sold and moved to the United States (the quoted words are all Pratt’s).[49] Following a similarly racist belief, Pratt’s Native American education model aimed at thoroughly “Americanizing” the children by severing their ties with their tribes: they were forced to live far away from their families, in addition to changing their Indian names, appearance, and languages.

In his portrait with Timento, Matsura appears to go against the assimilationist push and “Americanizes” himself by becoming Indian. The image could be read as a multivalent visual statement that confronts the negative connotations associated with blanket-wearing Native Americans. Matsura chose to “go native,” albeit only on film; or, more precisely, he assumed a hybrid persona that is simultaneously Asian (or “Oriental,” the adjective used in his contemporary vernacular) as indicated by his visible and unaltered face, and “Indian,” signified by the blanket that envelops and transforms his body. By layering (literally) a signifier of difference/minority on top of his difference/minority as a Japanese alien, Matsura creates a photograph that can be considered a gesture of solidarity, an expression of alliance between an immigrant and a racial minority group that was facing multiple assaults on its members’ lives and existence.

In addition, by “playing couple” with a Methow woman, Matsura not only visually articulates his sense of belonging with the disenfranchised, but also offers a challenge to his (imagined) viewer: the implied intimacy or union in the picture recalls the contentious issue of miscegenation—a made-up word, referring to interracial sexual contacts or marriages, that first appeared in 1863 during the American Civil War.

As Jolie A. Sheffer points out, even as there were visible exogamous unions in the early twentieth century, interracial coupling or marriage “provoked widespread anxiety” among white Americans.[50] This anxiety was caused by the fact that miscegenation blurred boundaries between races and promised to upset an established social order maintained by the white majority (supremacy). The threat was deemed so real that miscegenation laws (or antimiscegenation laws) were enacted, between the 1660s and the 1960s, to criminalize interracial marriage and sex.

According to the late historian Peggy Pascoe, states and colonies throughout the southern and western United States that passed miscegenation laws numbered forty-one at one time or another. Earlier laws focused on separating whites from blacks, but by the early twentieth century, “12 states targeted American Indians, 14 [included] Asian Americans (Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans), and 9 [included] ‘Malays’ (or Filipinos)” in their bans.[51] In 1868, Washington was the lone state in the continental West to vote down its proposed antimiscegenation law, but interracial sex and marriage remained a controversial issue, as the legal historian Jason A. Gillmer reminds us. In fact, a piece of state legislature was introduced in 1855 to make it illegal for whites to marry either blacks or Indians under a strict “blood purity” measurement that encompassed those who “possessed of one-fourth or more negro blood, or more than one-half Indian blood.” Those who “officiated an interracial marriage” would be fined between fifty and five hundred dollars.[52]

As a Japanese man, Matsura was legally free to have a relationship with or marry an Indian woman, though there has been no proof of his having courted or partnered with any women, Native, Japanese, or white. There is also no visual record showing that interracial couples actually had their portraits taken in Matsura’s studio. Matsura’s self-portrait with Timento was thus not to be taken as a “real” portrait but instead as a pictorial construct: a performance through which both Matsura and Timento raised real questions of the day.

The heterosexual pairing in the photograph points to a possibility of procreation, and with procreation comes the promise of posterity. With Timento’s quiet determination and Matsura’s concerned look, the (pretend) couple seem to ask: What would become of us, and of our offspring? Viewed against the backdrop of a dominant “vanishing race” narrative, with its underlying assimilationist erasure of difference, the portrait ostensibly offers an alternative for a Native American posterity, achievable by joining forces among the racial minorities—an alliance between Others. The portrait most touchingly illustrates, I think, Matsura’s close relationship and identification with his Native American friends in Okanogan. But it is also a poignant image, for it is a photographic fiction of sorts, of posterity that exists solely in pictures, as Matsura’s knowing gaze seems to acknowledge. And in hindsight, the 1912 portrait became an image of posterity for Matsura, who died a bachelor at the age of thirty-nine.

This short study has offered a close reading of Matsura’s portraiture by framing his photography as a diasporic artist’s critical means of engagement with a borderland and its people. Considered in this context, Matsura and Susan Timento Pose at Studio emerges as a multivalent visual statement produced by an astute image-maker whose work predates our identity-conscious visual production vis-à-vis issues of migration and diasporas. As such, Matsura’s extensive oeuvre invites and merits more scholarly attention.

ShiPu Wang is Associate Professor of Art History and a founding faculty member of the Global Arts Studies Program (GASP) at the University of California, Merced. He specializes in early twentieth-century American art and visual culture, with a focus on discourses of race and nationalism concerning the work of American artists of Asian descent. He is the author of Becoming American? The Art and Identity Crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi (University of Hawaii Press, 2011) and is writing his second book on a few lesser-known Asian American modernists.

Works Cited

- Fitzgerald, Georgene Davis. Frank S. Matsura: A Scrapbook. Okanogan County Historical Society, 2007.

- Frank S. Matsura Photographs 1907–1913, PC 35, Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries. http://content.libraries.wsu.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/matsura

- Gillmer, Jason A. “Crimes of Passion: The Regulation of Interracial Sex in Washington, 1855–1950,” Gonzaga Law Review 47:2 (2011): 393–428.

- Green, Rayna. “Rosebuds of the Plateau: Frank Matsura and the Fainting Couch Aesthetic.” In Partial Recall: With Photographs of Native North Americans. Lucy R. Lippard, ed. New York: The New Press, 1992, 51–52.

- Harpster, Kristin. Visions and Transgressions in Early-Twentieth-Century Okanogan: The Photography of Frank Matsura. Master’s thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, 1998.

- Kurihara, Tatsuo [栗原達男]. A Man Named Frank: Memories of Sakae Matsuura, Photographer of the West [フランクと呼ばれた男: 西部の写真家「松浦栄」の軌跡]. Tokyo: Jōhō Sentā Shuppankyoku, 1993.

- Lohrmann, Charles J., and Robert W. Kapoun. Language of the Robe: American Indian Trade Blankets. Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith Books, 1992.

- Mimura, Glen M. “A Dying West? Reimagining the Frontier in Frank Matsura’s Photography, 1903–1913.” American Quarterly 62.3 (2010): 687–716.

- Morgan, Murray. Introduction. In JoAnn Roe, Frank Matsura: Frontier Photographer. Seattle: Madrona Publishers, 1981.

- Pascoe, Peggy. “Miscegenation Law, Court Cases, and Ideologies of ‘Race’ in Twentieth-Century America.” The Journal of American History 83.1 (1996): 44–69.

- Pratt, Richard H. “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites.” In Americanizing the American Indians: Writings by the “Friends of the Indian” 1880–1900. Francis Paul Prucha, ed. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1973, 260–71.

- Roe, JoAnne, Frank Matsura: Frontier Photographer. Seattle: Madrona Publishers, 1981.

- Sekula, Allan. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39 (Winter, 1986): 3–64.

- Sheffer, Jolie A. The Romance of Race Incest, Miscegenation, and Multiculturalism in the United States, 1880–1930. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

- Sobania, Neal. “Hope and Japan: Early Ties.” The Hope College Alumni Newspaper, December 1998. http://www.hope.edu/academic/language/japanese/earlyties.html

- Wilson, Bruce A. “The Life of a Working Girl.” Okanogan County Heritage 22:3 (Summer, 1984): 21–25.

Notes

The photograph is in Frank S. Matsura Photographs 1907–1913, Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC), Washington State University Libraries. Thanks to Mark O’English, University Archivist at MASC, for helping me obtain study images and high-resolution reproductions.

I must acknowledge JoAnn Roe, and Marilyn Moses at the Okanogan Historical Society, for responding to my research inquiries in the past few years. I also thank Sharon Spain and Mark Johnson for introducing me to Matsura’s work in 2005.

I have in mind the French photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson’s collaboration with the Countess da Castiglione between 1856 and 1895, which resulted in more than 400 portraits of the countess presenting herself in a myriad of styles and settings. See, among others, Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “The Legs of the Countess” (1986), reprinted in Fetishism as Cultural Discourse, Emily Apter and William Pletz, eds. (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1993), 266–306; and Pierre Apraxine and Xavier Demange. “La Divine Comtesse”: Photographs of the Countess de Castiglione. Exhibition catalogue. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

A detailed examination of these artists’ differences is beyond the scope of this essay. For more extensive studies see, among others, Margo Machida, “Out of Asia. Negotiating Asian Identities in America,” in Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art (New York: Asia Society Galleries, 1994), 96–98; Nikki S. Lee, Russell Ferguson, Gilbert Vicario, and Lesley A. Martin, Projects (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2001); Nikki S. Lee and RoseLee Goldberg, Parts (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2005); Tseng Kwong Chi: Self Portraits 1979–1989 (New York: Paul Kasmin Gallery, 2008); Cherise Smith, Enacting Others: Politics of Identity in Eleanor Antin, Nikki S. Lee, Adrian Piper, and Anna Deavere Smith (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011).

Most of the earlier writings available in English focused on piecing together Matsura’s biography and his varied repertoire. JoAnn Roe, a Washington-based writer who has made great efforts to uncover Matsura’s life stories, wrote extensively about Matsura’s time in the Okanogan region. Her seminal works, among them Frank Matsura: Frontier Photographer (Madrona Publishers, 1981), which is cited in this study, provide invaluable sources for subsequent research. As a master’s candidate at Washington State University, Kristin Harpster offered in her thesis, Visions and Transgressions in Early-Twentieth-Century Okanogan: The Photography of Frank Matsura (Washington State University Pullman, 1998), the most analytical study of Matsura’s pictures that was available during our curatorial research in 2005.

The biographical information I use here is drawn largely from Roe’s research and a Matsura chronology in English, “Timeline for Sakae (Frank) Matsura,” in Georgene Davis Fitzgerald’s Frank S. Matsura: A Scrapbook (Okanogan County Historical Society, 2007), 62–63, as well as the biography, written in Japanese, by Tatsuo Kurihara, A Man Named Frank: Memories of Sakae Matsuura, Photographer of the West [フランクと呼ばれた男: 西部の写真家「松浦栄」の軌跡]. Tokyo: Jōhō Sentā Shuppankyoku, 1993 (partially translated by Lin-Dai Tsai and me). Fitzgerald’s publication provides invaluable resources, including transcribed newspaper reports that I incorporated into this study.

In The Okanogan Record, 14 April 1905, the name appeared as “Frank Matsura,” whereas in various reports in 1904 it was spelled “Matsuura” in the same newspaper. The reports are transcribed in Fitzgerald’s Scrapbook, 50–51.

Kurihara, 43–47. I use one of several possible English transliterations of Okami’s first name here. As the pronunciation of one’s name could vary, even though the Kanji character could be the same, “正” could also be “Masashi” or “Sho.”

After earning his teaching credentials and certificate, Okami became a lecturer and eventually the principal of the Shōei Elementary School (1886–1907), where a twenty-year-old Matsura taught at the Sunday school and from 1993 to 1996 assisted in administrative work. Okami also taught at the Shōei Girls’ Junior and Senior High School (頌栄女子学院) and other schools for several years. Kurihara, 61.

Neal Sobania, “Hope and Japan: Early Ties,” in The Hope College Alumni Newspaper, December 1998. http://www.hope.edu/academic/language/japanese/earlyties.html

Kurihara, 60–68. The first large-scale retrospective of Shimooka’s photography was organized by the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography and was on display from March to May 2014. For Shimooka’s work and life, see Keishō Ishiguro, ed., Renjō Shimooka: The Pioneer Photographer in Japan 下岡蓮杖写真集 (Tōkyō: Shinchōsha, 1999); and Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, ed., 328 Outstanding Japanese Photographers 日本写真家事典 (Kyoto: Tankōsha, 2000).

Roe, 21. For an online resources site maintained by the Colville Tribes, see: http://www.colvilletribes.com/history_of_the_colvilles.php.

Bruce A. Wilson, “The Life of a Working Girl,” Okanogan County Heritage 22:3 (1984), 22.

Frank S. Matsura Photographs 1907–1913, Negative 35-22-05. Established by the Pacific Fur Company in 1811, Fort Okanogan was the first American trade outpost in the state of Washington. For relevant local history, see William Compton Brown, Early Okanogan History (Seattle: Ye Galleon Press, 1968).

See, for example, Negatives 35-12-27 and 35-08-83, among many others, in Frank S. Matsura Photographs 1907–1913.

Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” in October 39 (Winter 1986), 6.

For example, the French photographer Hippolyte Bayard (1801–1887) created his famed Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man in 1840, following Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) in France and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) in England, who reportedly preempted Bayard in announcing their invention of photography, in 1939. Bayard, obviously, did not actually commit suicide by drowning. The picture, which could be taken by an unknowing viewer as an eye-witness record, was used by the photographer as a statement.

For more on Chief Joseph, see, among others: Joseph Young, Chief of the Nez Perce, “An Indian’s Views of Indian Affairs,” in The North American Review, vol. 128, issue 269 (April 1879), 412–34; Robert R. McCoy, Chief Joseph, Yellow Wolf and the Creation of Nez Perce History in the Pacific Northwest: Indigenous Peoples and Politics (New York: Routledge, 2004); and Thomas H. Guthrie, “Good Words: Chief Joseph and the Production of Indian Speech(es), Texts, and Subjects,” in Ethnohistory 54:3 (Summer 2007): 509–46.

Glen M. Mimura, “A Dying West? Reimagining the Frontier in Frank Matsura’s Photography, 1903–1913,” in American Quarterly 62.3 (2010): 693.

With the sponsorship of John Pierpont “J. P.” Morgan (1837–1913) and President Theodore Roosevelt’s endorsement, Curtis took more than forty thousand photographs in twenty-three years. Serving also as an ethnologist, Curtis recorded and documented Native languages, music and songs, customs, traditions, and biographies. Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian (Cambridge, Mass.: The University Press, 1907).

Photogravure is a process of transferring an image from a film negative to a metal plate. The image is etched into the plate, from which reproductions are made. For a concise explanation of photogravure, see David Morrish and Marlene MacCallum, Copper Plate Photogravure: Demystifying the Process (Amsterdam: Focal Press, 2003). For useful online resources concerning photogravure, visit http://www.photogravure.com.

Rayna Green, “Rosebuds of the Plateau: Frank Matsura and the Fainting Couch Aesthetic,” in Partial Recall: Photographs of Native North Americans. Lucy R. Lippard, ed. (New York: The New Press, 1992), 51–52.

Moorhouse’s untitled young female portrait is in the Moorhouse (Major Lee) Photographs Collection, University of Oregon Libraries Special Collections and University Archives, PH036_4891. http://oregondigital.org/u?/Bestof,1362

Harpster, 107. Harpster interviewed Tim Brooks, of the Colville Reservation Museum (October 3, 1998), who offered his grandmothers’ recollections of Frank Matsura: “Colville Indians called Matsura the ‘photo man.’” Harpster asked how Matsura negotiated control of the posing and performing evident in his photos: “Mr. Brooks had heard that Indians were pleased that Matsura was preserving their history by recording them not only in their tribal dress (which he said they voluntarily wore to his studio), but also while wearing workclothes [sic]. They thought he captured a changing time by photographing them in settings that reflected the move away from teepees and into frame homes. Apparently, they felt that Matsura’s photographs would make viewers realize the changes occurring on the Colville Reservation. Mr. Brooks said further that they thought Matsura took funny photographs. . . . They liked him, though, so in Mr. Brooks’s words, ‘they went along with it.’”

My statement concerns this specific, published image by Curtis, however. As the anthropologist-artist Aaron Glass has shown in his essay, in a different version of the same figure, the Hamat’sa shaman looks straight at Curtis’s camera. That gaze would force the viewer to consider the image-making process and in turn the confrontation between the camera and the shaman—a realization of the Native person’s existence in a contemporary sense that may not have been desirable for Curtis’s pictorial narrative. Aaron Glass, “A Cannibal in the Archive: Performance, Materiality, and (In)Visibility in Unpublished Edward Curtis Photographs of the Kwakwaka’wakw Hamat’sa,” in Visual Anthropology Review 25:2 (Fall 2009): 131.

The Washington State University’s records show that Timento was an aunt of Cecil Chiliwhist. The information associated with Matsura’s Cecil Chiliwhist and Her Aunt Pose at Matsura’s Studio, ca. 1910, shows that Cecil Chiliwhist was a Methow Indian who lived in the Malott area and ranched. The Methow lived on the Methow River, which entered the Columbia River in north-central Washington, and their population had been in a steady decline—from the recorded eight hundred (including the Sinkius) in 1780 to three hundred in the early 1870s. Robert H. Ruby and John Arthur Brown, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986), 129–130.

My thanks to Barry Friedman, a pioneer collector and dealer of Indian trade blankets, for taking the time to answer my inquiries and suggesting readings. Friedman’s Chasing Rainbows: Collecting American Indian Trade & Camp Blankets (Bulfinch Press, 2003), is considered an indispensable book in the studies of American Indian blankets.

Charles J. Lohrmann and Robert W. Kapoun, Language of the Robe: American Indian Trade Blankets (Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith Books, 1992), 10–11. Rain Parrish, of Navajo descent, and Bob Block, of Osage descent, provide their personal experiences and understanding in the “Native American Perspective on the Trade Blanket” section, 1–5. Lohrmann points out that the understanding of the robe was deemed important enough for the Bureau of American Ethnology to compile and publish an extensive explanation of “the language of the robe” in 1905.

There is a wealth of literature on the contested history of the assimilation of Native Americans. For publications relevant to the period in which Matsura worked, see, for example, Francis Paul Prucha, Americanizing the American Indians (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1973); S. Lyman Tyler, A History of Indian Policy (Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1973); Frederick Hoxie, A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984); David E. Wilkins and K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Uneven Ground: American Indian Sovereignty and Federal Law (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002); Fred A. Seaton and Elmer F. Bennett, Federal Indian Law (Clark, N.J.: The Lawbook Exchange, 2008).

Richard H. Pratt, “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites” in Americanizing the American Indians: Writings by the “Friends of the Indian” 1880–1900. Francis Paul Prucha, ed. (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1973), 260.

Pratt’s original paper was delivered at the National Conference on Social Welfare and reproduced in Philip C. Garrett’s The Indian Policy Papers Read at the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction (1892), 46–59. For more studies on the boarding schools and their impact, see also David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995); and S. A. Colmant, “U.S. and Canadian Boarding Schools: A Review, Past and Present,” in Native American Journal 17:4 (2000): 24–30.

Jolie A. Sheffer, The Romance of Race Incest, Miscegenation, and Multiculturalism in the United States, 1880–1930 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 160.

Peggy Pascoe, “Miscegenation Law, Court Cases, and Ideologies of ‘Race’ in Twentieth-Century America,” in Journal of American History 83:1 (1996): 48–49. See also Pascoe’s “Race, Gender, and Intercultural Relations: The Case of Interracial Marriage,” in Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies 12:1 (1991): 5–18; and her What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (Oxford, UK; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Jason A. Gillmer, “Crimes of Passion: The Regulation of Interracial Sex in Washington, 1855–1950,” in Gonzaga Law Review 47:2 (2011): 401, 405. In note 47, Gillmer quotes the language of the legislature, Act of January 29, 1855, § 1, 1854–1855 Wash. Sess. Laws 33, 33, which is worth repeating here: “[A]ll marriages heretofore solemnized in this territory, where one of the parties to such marriage shall be a white person, and the other possessed of one-fourth or more negro blood, or more than one- half Indian blood, are hereby declared void.” The repeal was enacted by Act of January 23, 1868, § 1, 1867–1868 Wash. Sess. Laws 47, 47–48.