Diasporic Vietnamese Family Photographs, Orphan Images, and the Art of Recollection

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen yearns for a box of photos her family shipped to their temporary home in Japan in 1975, a box that never arrived. The journalist Andrew Lam confesses to the “unforgivable act” of burning his family photos, which reduced three generations to ashes.[1] During her first journey back to Vietnam in thirty years, Kim’s hired car circles the roads of Bien Hoa, a town just south of Saigon, in search of the photo studio where dozens of her portraits were kept, only to learn that the owners have emigrated and no one knows what happened to these old photos. She returns to her home in Ontario, disappointed and bereft.[2]

Such stories of visual yearning are familiar to the Vietnamese diaspora. They are especially poignant for the first wave of refugees, those who fled in 1975, in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Saigon, as well as for the second wave, the “boat people,” whose plight gave rise to the Indochinese humanitarian crisis of the late 1970s to the early 2000s.[3] For these two groups, photos are an often fraught, incomplete record of a painful past.

As they awaited their chance to flee, refugees hid, altered, abandoned, buried, or even burned photos that contained incriminating evidence of collaboration with Americans and loyalty to the defeated Republic of Vietnam. Many of those who fled abandoned compromising pictures in the name of survival. For others, photos that remained intact were left behind to make room for jewelry with which to barter and enough food to keep them going.

Photographs lie at the core of the Vietnamese diaspora, especially for those who struggle to piece together incomplete stories told by images, many of which were defaced, discarded, or destroyed. At the same time, such photos represent a tie to the families left behind, whether as memories of artifacts that no longer exist or as surviving images that evoke layers of memories.

Despite the prominence of these stories of visual longing among diasporic Vietnamese, however, few critics have paid careful attention to them. How has photography — especially family photography — affected this community? This paper explores the function of family images in recent projects by first- and second-wave refugees.

Family photos are probably not what come immediately to mind when envisioning the Vietnamese diaspora. As a highly conventional and deeply personal genre associated with the shy smiles, chagrined grimaces, and surprised joy that greet such bourgeois rites of passage as birthdays, graduations, weddings, housewarmings, and vacations, family photos seem far removed from the experiences of war that profoundly shaped scores of refugees, the groups directly affected by the war and its aftermath. Given this dominant framework of war, a consideration of documentary or combat photography might seem more apt. Indeed, studies of the war in Vietnam dwell on the same handful of award-winning images, particularly Malcolm Browne’s Burning Monk (1963), Eddie Adams’s picture of a public execution (1968), and Nick Ut’s depiction of the victims of a napalm attack in Trang Bang (1972). This narrow selection of images is circulated widely and reproduced endlessly to illustrate the grisly spectacle of violence as an object lesson on American militarism.

The problem with brooding on such a grim group of images is that they often present the occasion for focusing on American experiences, despite the fact that they depict the wounding of Vietnamese bodies,[4] and emphasize the extraordinary dimensions of war. In so doing, the experiences of the Vietnamese, with their subtle but no less meaningful narratives of everyday people and ordinary wartime conditions, are obscured. In fact, the ubiquity of these violent spectacles may even account for why family photos have been largely overlooked by scholars of area studies and of visual studies.

Family photos are relevant because of, not despite, their quotidian qualities. When it comes to understanding the visual culture of the Vietnamese diaspora, family photos increasingly interest me more than these other iconic images do: As a record of the conventional, domestic images provide a way to refocus discussion of war and its aftermath. Family photos nudge us away from familiar spectacles of violence to consider instead the daily struggles to survive.

Family photos also matter because of the Vietnamese politicization of family. In The Other Cold War, the anthropologist Heonik Kwon explores how “wartime political bifurcation” fractures the “genealogical unity” of communities in Vietnam well after the war’s end.[5] These communities are torn between the familial responsibility to honor those members who died in the war — and most families had relatives who fought for both sides — and the political duty to preserve the memories of revolutionary martyrs. Because the latter is a sanctioned, legitimate public rite and the former is not, these communities must reconcile tensions that arise when state obligations trump family responsibilities. Kwon’s study of a community located in central Vietnam finds private ancestral altars, where photos of the departed who fought on either side are honored together, function as a way to unify the dead in kinship memory. This practice tacitly opposes official state history. In the case of the Vietnamese families documented by Kwon, kinship memory sutures treacherous political bifurcations that persist beyond the war’s end and despite the nation’s reunification.

Although Kwon’s ethnography focuses on families in postwar Vietnam and their connection to the wartime dead, still-living diasporic Vietnamese families also brush up against the knots he uncovers; these political bifurcations entangle families’ links with each other and with those left behind. Huynh Thuy Ai Lan movingly recounts the persecution she encountered: “[S]ome policemen concluded I was a CIA agent because they had found a photograph of me with an American. I explained that he had been my English teacher and the photo was taken at his farewell party, but that made no impression at all.”[6] This scrutiny of revolutionary credentials may have influenced the very look of families and altered their constitution beyond the expected blood relationship. In her ethnographic study of Vietnamese communities in Australia, Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen observes that the telling bars of a uniform belonging to the southern Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) are excised from a family photo that had made its way out of Vietnam.[7] It is not just uniforms that were eradicated from the family record; in some cases, those who wore these uniforms were erased.

Attending to how family photos are taken up by the Vietnamese diaspora unsettles the assumption, long held in photographic studies, that the family largely serves the ends of the state by reproducing gendered, classist, and heteronormative ideologies.[8] The act of preserving kinship memories, by honoring the ancestral rites documented in Kwon’s ethnography—and, I might add, by safeguarding once renounced family photos to include in these rites or for other purposes—may not reproduce state ideologies but instead defy them. Indeed, at times they do so in ways, as I touch on below, that converge with neoliberal humanism. Conversely, the alteration or destruction of family photos, acts that transform the very look of a family, attempt to dodge rather than consent to state surveillance. Seen in this light, even the most banal of family photos, a genre that is, after all, distinguished by its unremarkable conventionality, acquires heightened importance. And yet, for these reasons, family photos of the Vietnamese diaspora are not readily accessible. In some cases, in fact, they have barely even been preserved by family archivists, never mind tidily cataloged and stored within official archives such as libraries and museums, institutions that, as the archival theorist Joan Schwartz observes, have been slow to recognize the significance of vernacular artifacts.[9] The task of looking at family photos necessitates looking for them.

Accordingly, this paper turns not to official archives, which offer scant information about family photos, nor to the communities themselves, though this ethnographic research is worth pursuing, but rather to collecting projects that have recently been initiated from within the Vietnamese diaspora itself. A select group of artists, activists, and public historians who are themselves part of the first and second waves of mass migration are starting to ponder the significance of family photos in wide-ranging projects that draw on these domestic images in order to provoke new ways of seeing displacement and resettlement, and of understanding the processes of recollection. Among these projects, to name only a few, are: “Vietnam in the Rearview Mirror,” an ongoing exhibition at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle; The Boat People, Carina Hoang’s illustrated collection of oral histories; the blogger Andrew Ngo’s online photos of Pulau Bidong,[10] a remote beach that is the site of a well-known refugee camp in Malaysia; the recently launched The Making of an Archive, Jacqueline Hoang Nguyen’s interactive digitizing initiative;[11] and a trinity of multimedia installations by Dinh Q. Lê, a Vietnamese-American artist now based in Ho Chi Minh City, titled Mot Coi Di Ve (1998), Erasure (2011),and Crossing the Farther Shore (2014).[12]

This paper provides a critical description and review of some of these projects, with a focus on the most well known of them, the multimedia installations by Dinh Q. Lê,, an internationally recognized artist. The projects under discussion display diverse perspectives on photography but they exhibit a strikingly similar approach. Specifically, they all draw on diasporic communities to gather and assemble family photos, some of them precious artifacts donated by families but many more of them lost and subsequently “found” orphaned images that have been removed from albums and which disclose little about who they portray or where and with whom they belong.

These projects disclose a fervent compulsion to amass, one that then raises questions about the significance of the act of collecting. What relationship might exist between collecting family photos and the formation of a diasporic sense of collectivity? When little or nothing is known about a family, as is the case with thousands of found photos that found their way into collecting projects, what affiliations and disaffiliations are evoked by orphan images, and what meanings are attached to these poignant, anonymous images?

Through a consideration of how these works integrate and engage with family photos, I hope to offer preliminary reflections on some of the issues raised by this concern with collecting family photos: on, for example, the complications orphan images introduce to the very notion of family and the affective resonances of sparking a sense of collectivity both within the diaspora and in relation to those in Vietnam, who, perhaps, are supplying the photos that are being avidly collected.

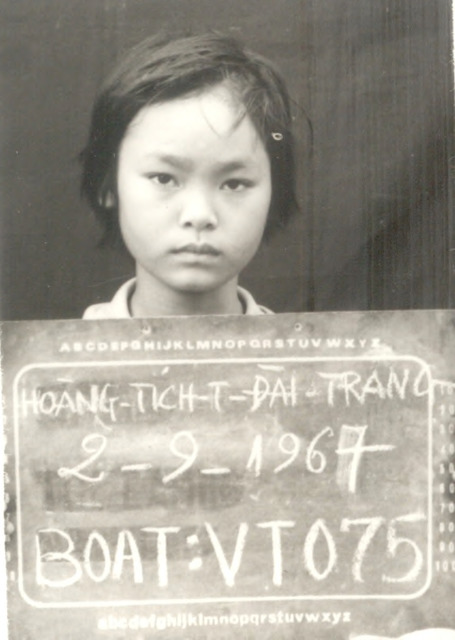

A man and a woman stand against the improvised backdrop of a pale sheet and peer unsmilingly at the camera. With their two toddlers standing before them, the woman cradles a third child, a baby, while the man clutches a card that identifies the boat they arrived in, BT001578. Refugee ID photos may portray a family, but the somber picture this portrait draws of dangers barely overcome and adversities still to be endured is hardly what one expects of a family photo. Because it conjures unhappy themes of destitution and desperation, the photograph seems, at first glance, an unlikely choice for the cover image of “Vietnam in the Rearview Mirror.” Surely, most families would chafe at the prospect of recognizing themselves in the grim, wide-eyed stares that so disturbingly resemble the victim motif described by Martha Rosler in her critique of documentary photography.[13] In its presentation of people as numbers—the initials stand for the name of the boat the family arrived in; the digits indicate the date and the total members in this family—the photo seems far removed from the kind that undertakes to illuminate what the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu calls the middlebrow “familial functions” [14] of recording bourgeois rites in recognition and embrace of kinship. With the numbers enabling administrators to determine who is at the refugee camp and how many rations are needed, the image fulfills the function of instrumental photography: to make subjects legible and governable.

Though it is the only ID photo in the exhibition, a close look reveals why it was selected to promote “Vietnam in the Rearview”: The surface of the picture is as creased as the sheeted backdrop is wrinkled. These signs of wear are a disclosure of the tactile dimensions of feeling when it comes to photography; indeed, the exhibit director explains that this photo was chosen because it is “such a compelling image.”[15] These textural signs suggest that many people handled the photograph; it was probably passed from photographer to camp administrators, then to members of the family themselves, who, after a difficult passage, likely held on to it for decades.

This nexus of exchange, from one institution to several others, bears out Allan Sekula’s insight that instrumental photography can be seen as the shadow archive of bourgeois portraiture: that is, the subjection of the former subtends the humanism of the latter. At the same time, as numerous critics have observed, this genre of family photography is remarkable because of the complexities of the “familial gaze,” Marianne Hirsch’s helpful term to describe how family photos from the intimate preserve of the private sphere intersect with and move among multiple public spheres. The genre of family photos, Hirsch points out, comprise the usual snapshots and studio portraits that are contained within private albums, but these albums may harbor less conventional images as well. In this regard, ID photos produced by the state for the purposes of surveillance may find their way into the sanctuary of a family.[16]

Refugee ID photos, though, contain a paradox,[17] for they expose the predicament of human rights. As Hannah Arendt eloquently writes, the fragile condition of the merely human may not protect subjects but instead render them to abuse: “Man, it turns out, can lose all so-called Rights of Man without losing his essential quality as man, his human dignity.”[18] As a means of aiding these subjects, ID photos ironically reduce them into numbers. However, the exhibition’s prominent display of the refugee ID photo reverses its primary purpose: it humanizes the subject. Although Sekula’s concept of the shadow archive reminds us of how instrumental photography undermines the humanism of bourgeois portraiture, the inclusion of refugee ID photos as family pictures flips this structure.

“Vietnam in the Rearview” effectively reclaims this instrumental image as a family photo. In so doing, the exhibition acknowledges the unsettling possibility that refugee ID photos form a haunting part of Vietnamese people’s visual narratives and expand the genre of family photography: the family emerges to counter the dehumanizing logic of the ID photos’ numbering system and the condition of statelessness that renders refugees vulnerable.

An issue the inclusion of this ID photo sparks is how to define the very nature of what constitutes “family.” Whereas this particular image seems to spotlight a nuclear family, oral histories of first-and second-wave diasporic Vietnamese offer accounts of experiences that broaden the concept of family beyond this conventionally limited grouping.[19] Further research on refugee IDs and their inclusion within the collections of diasporic Vietnamese might extend our understanding of both family and family photos.

By dispensing with mobility and instead embracing the theme of national settlement, the exhibition also reverses the relationship between between humanism and subjection, or the process by which subjects are compelled to submit to powerful forces. If Vietnam is in the “rearview,” the refugee ID photo is a turning point in the journey to the United States, so that the politics of representation that the exhibit embraces counters the earlier period of vulnerability.. Drawing implicitly on the before and after convention, which Shawn Michelle Smith and Laura Wexler associate with moral reform,[20] to emphasize progress and self-fashioning, the “Vietnam in the Rearview” exhibit effectively reclaims this instrumental image as a family photo.

At the same time, the inclusion of refugee ID documents as family photos intersects with the discourse of neoliberal humanism. The implicit before/after structure that upholds self-fashioning as a counter to the violence of subjection invokes a controversial form of identity politics, one that has been critiqued by scholars of ethnic studies for more than a decade. As the critical refugee studies scholar Yen Le Espiritu argues, humanitarian missions often have ideological motives. She contends that the neoliberal commitment of such nations as the United States to humanitarian intervention in response to the Indochinese-refugee crisis marks, not a departure from the militarism that gave rise to proxy wars in Southeast Asia, but rather an extension of it; such missions ensured a moral victory for America as compensation for the humiliating military defeat of the Vietnam War.[21]

In this regard, the inclusion of refugee ID photos within the discourse of diasporic family humanizes subjects in a way that mirrors the logic of neoliberal humanism. The merging of instrumental photography and family photography thus exposes an underlying tension between the surveillance of subjection and identity politics: the latter’s gestures of defiance, in response to a history that threatened to erase subjectivity altogether, confronts the seemingly inevitable and deeply ironic compromise of fashioning selfhood in the image crafted by the former.

The before-and-after convention is nevertheless a powerful technique, one also employed by the oral historian Carina Hoang to structure her illustrated book, The Boat People: Personal Stories from the Vietnamese Exodus, for the similar end of drawing on refugee ID photos as a resource in piecing together a narrative of family survival and remembrance. This strategy likewise echoes neoliberal humanism through its embrace of identity politics: each of her oral histories is bookended with an older photograph, sometimes from Vietnam, at other times from the refugee camps, and a more contemporary photograph, to mark continuity and change, survival and transformation. The latter images are accompanied by captions that sound the high notes of success—degrees earned, prizes awarded, families held together—and visually emphasize this theme through the use of vivid color that contrasts with, while redeeming and uplifting, the sepia-tinged somberness of pitiable earlier images.[22]

In addition to having an implicit before/after structure, Carina Hoang’s project is strikingly similar to others in actively drawing on the communities it seeks to supply the photographs that represent them. Wing Luke Museum accepted donations from its Advisory Board and local diasporic communities; Hoang compiled her oral histories by soliciting contributions via her website and in Vietnamese-language newspapers in the United States and Australia; in a more informal fashion, Andrew Ngo calls on other refugees who passed through Pulau Bidong, a Malaysian camp that from 1978 to 1991 hosted up to a quarter million refugees, to share stories, memories, and photographs through his blog, “The Boat People.”

Currently, Jacqueline Hoang Nguyen, a Vietnamese Canadian artist now based in Switzerland, is soliciting donations in collaboration with Gendai Gallery, in Toronto, for The Making of an Archive. Although it does not focus on the Vietnamese diaspora (the aim of Nguyen’s project is to represent the diverse experiences of all diasporic Canadians), this work is inspired by the role of photography in mediating her family’s immigrant experiences. By offering digitizing workshops to participants in exchange for a digital copy of their photos, Nguyen’s project suggests that an archive is made through a call–and–collective response that enables communal interaction. The method of crowd-sourcing photographs and accompanying narratives aspires to reconstitute fractured families through digital preservation — through the work of archiving — to create the very communities the project describes. In effect, this project strives to spark a sense of collectivity through collection.

The work of Dinh Q. Lê, a diasporic Vietnamese artist now based in Ho Chi Minh City, likewise kindles a collective sensibility through the collection of family photos. As is the case with Hoang, Ngo, and Nguyen, Lê is drawn to family photos for personal reasons. In the turmoil of his hasty departure from Vietnam, his family photos were lost. After his return to Vietnam, in the late 1990s, he scoured the booming southern city’s antique shops in search of these images. He found family photos, tens of thousands of them, but they were not of his family.

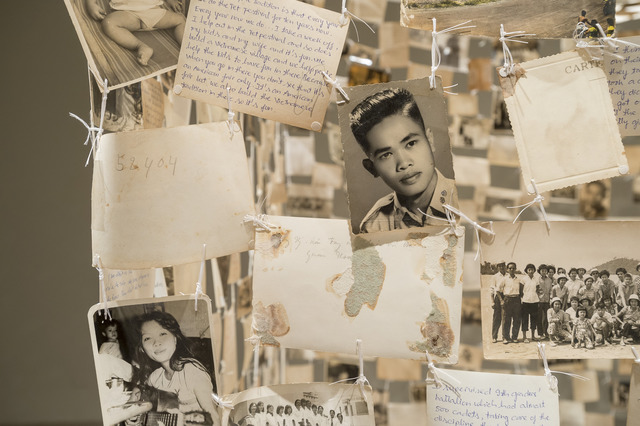

Found family photos form the core of some of his most arresting work. In Mot Coi Di Ve (a title that takes its name from a popular Vietnamese song, translated as “A Place to Leave from and Return To”), a 1998 installation, approximately 1500 are stitched together and hang like a fragmented curtain or screen on a gallery wall, the empty spaces among the images poignant statements of loss as the figures peer out from each of the photos. Although the found photos suggest one can still perceive that which was left behind, the gaps, through which only the gallery’s blank white wall is visible, reveal that one can never fully return. The installation forms a fitting vision of the diasporic subject’s predicament of displacement, all the more heartbreaking given that Le has chosen to return to and settle in Vietnam.

A more recent work, Erasure (2011), invites visitors to trace a trail of visual artifacts scattered in the course of the refugee’s perilous journey. The installation features a boat wrecked amid a sea of discarded photos, 180 kilograms worth, according to the artistand the flotsam and jetsam of torn jeans and ragged shirts. Visible yet irretrievable, the photos form a broken path that links overseas Vietnamese to dispersed families, the textures of fabrics a complement to the curled edges of the found photos, so that the combination of paper and cloth comprises a tactile sense.[23] Removed from their albums and bearing scant if any identifying features, these are orphan images. Who are these people? To whom do these photos belong? To address these questions, Erasure encourages visitors to witness what Le describes as the “liquidation” of personal memory through their voyage across this chaotic swirl of images, churned up in the course of a violent passage.

Just as significant, Erasure is an archiving project. The impersonal whirr of a digital computer scanner alerts visitors to the storing and ordering of each of these orphan images, unidentified and discarded, a process that also transforms the very objects being preserved, smoothing out the affective textures of memory. Prints become pixels, the forgotten memories externalized. They are uploaded to an online database that complements the installation, one that draws on crowd-sourcing from an international community, but most likely comprising the overseas Vietnamese, to claim that which was left behind.[24] However, the extent to which they are actually claimed is unclear, and the project as a whole introduces a number of ethical issues, not least of which the vulnerability of the photos’ public exposure and availability to claiming by strangers, that remain unresolved. By separating while overlapping two parts of the installation, contemplation of found photos and digital compilation of them for the purposes of reclamation, Erasure merges the act of collecting into archiving. The installation begins as a collection, but in the digital form it continues to take long after it has been disassembled, Erasure preserves itself as an archive. In this manner, these found photos — foundlings or orphan images — are claimed.

I will address the significance of this archiving practice, but first I want to reflect on the concept of orphan images and the ways they fit, and the extent to which they fail to fit, within the genre of family photography.

By definition, orphan images disclose little about themselves. What we know comes largely by way of legal debates that refer to them as “orphan works,” those whose uncertain provenance poses a problem for determining copyright.[25] In response to one of the questions raised by this installation — to whom do these images belong? — the field of copyright law would ponder the identity of rights-holders. Tina M. Campt reminds us, however, in her important book on the black diaspora in Europe, that this evocative term connotes something else for the broader field of visual studies, in which scholars working with film consider orphan images to be a challenge for archival recuperation and preservation.[26] Following the logic of this second approach, such images belong in the repository of an archive where they can be seen, so that what was lost may be found and made known.

When it comes to the visual culture of the black diaspora, however, Campt finds this promise of legibility disquieting rather than reassuring. That orphan images belong to no one is precisely the point for Campt, who insists on the importance of “fugitivity” for defying knowledge regimes and their associated power, a concept that has special resonance when it comes to scholars of the black diaspora, who often grapple with the lingering legacy of slavery, even though this issue is perhaps less significant in Europe than it is in the Americas. (Though not explained explicitly as such in Campt’s work, the concept of fugitivity is inspired, surely, by the figure of the fugitive and her fabled revolt against slavery.) Orphan images need not be found in the sense celebrated within film studies, Campt argues, when the condition of loss offers the occasion for contesting the epistemological demands of these regimes. From this perspective, archives can be coercive because they threaten to destroy, or at least neutralize, the waywardness of orphan images.

Orphan images acquire yet another meaning when it comes to first- and second-wave members of the Vietnamese diaspora. In a context in which the state’s politicization of families results in their bifurcation, defiance can take the form of collecting and archiving instead of waywardness. In short, Campt’s provocative concept of fugitivity cannot simply be transposed onto the Vietnamese diaspora, whose transnational experiences as refugees are shaped not by the specter of slavery but rather, as I have shown, by this politicization of family. Thus, for the Vietnamese diaspora, the acts of collecting and archiving can be seen as symbolically defiant and reparative gestures, whether in the wake of the Vietnam state’s bifurcation of family loyalties in the postwar period, which makes the very preservation of kinship ties a suspicious and punishable act, or against the conditions of statelessness that would eradicate subjectivity, ironically through the production of ID photos.

This process of collecting and archiving attends to the nuances between different archival structures and exposes crucial distinctions between the violence of public history and the erasures of personal memory. These diasporic Vietnamese projects suggest that orphan images should be brought home to a collection, if not an archive in its official sense; at the very least, the collections reveal the conditions that have made the quest to come home impossible. The “orphan” is a figure that not only connotes the literal photographs from family albums, which were discarded in desperate haste, but also symbolizes the actual family members lost in the course of the journey, either because they could not come along or because they did not survive. Significantly, Lê has frequently referred to his found orphan images as a “surrogate” family album. In this sense, the embrace of the orphan image within collecting projects initiated by members of the Vietnamese diaspora can be seen as a gesture of reparation, if not repatriation, through symbolic acts of reunion.

By encouraging collective participation in this action through a call to claim these orphan images, no matter how haphazardly and impartially answered, Lê stretches the limits of family photos even further. Although family members presumably would be the ones to connect with the photos in his digital archive, this may not always be the case. Others can claim the photograph too: for example, there is the photographer, who is seldom pictured, and the unrelated person, the stranger, who sometimes appears. Erasure ends up challenging our definition of family by leaving open the possibility of multiple claims from unexpected sources — by allowing for what Nayan Shah calls, in a wholly different context, “stranger intimacy.”[27] Although Shah’s specific concern is the intersecting histories of immigration, race, and sexuality in the North American West, the concept of stranger intimacy aptly captures the alien affiliations and disaffiliations invoked by this installation.

By contrast, the larger question posed in in Lê’s digital Erasure archive is: Who are the families pictured? They may be strangers to him, but they are the ones he came upon and incorporated when he sought but could not find his own. They are the ones viewers could claim, though they may not recognize who is pictured in each family photo. Here, where the digital archive opens to anyone who fulfills the requirement of registering and logging on to the website where it is stored, the notion of a stranger intimacy conjured in this way ends up reframing “family.” This archiving project experiments with a form of kinship that extends beyond biology, but in a way that leaves uncertain the precise terms in which relationship is to be articulated.

Although the term “adoption” does not explicitly appear in the Erasure installation, this suggestive metaphor is implied through Lê’s handling of orphan images. Here I would like to pause briefly to reflect on the significance of the metaphor in light of debates on transnational and transracial adoption, a practice that emerged with the end of the Second World War and accelerated in the aftermath of the Korean War.

For critics in adoption studies, this practice generally assigns the burden of reproduction to developing nations in the south and confers moral authority to wealthier nations, in their role as benevolent rescuers, in the north, at the same time obscuring the material histories that have forced impoverished women to abandon their children.[28] (South Korea’s central role in the geopolitics of transnational adoptions, however, troubles this bipolar division of global north and south, which nevertheless persists and which I employ advisedly.) Such Cold War structures of feeling, with their politics of pity, have delineated what Alice Toby Volkman calls “new geographies of kinship,”[29] in effect producing, as David Eng points out, a multitude of diasporas that include the orphans and refugees spotlighted in Lê’s installation. Although these scholars have focused on the asymmetries of power between the adopting nations of the north and the abandoning nations of the south, few studies have remarked on how Cold War structures of feeling have informed the practice of intranational adoptions. Even fewer have considered the extent to which these new diasporic figures overlap.

In the context of the Vietnamese diaspora, for example, the notorious Operation Babylift, which entailed the removal of some two thousand Vietnamese babies during the fall of Saigon, in 1975, effectively merged two figures: these so-called orphans, many of whom actually had still-living parents, are at the same time refugees. How might these entanglements deepen — and how might they unravel — if refugees are the ones who adopt abandoned children?

To my knowledge, this question has yet to be taken up in a thorough way, but Lê’s Erasure installation addresses it in an oblique and symbolic manner, albeit without the consolation of easy answers or pat resolutions. By foregrounding orphan images as the remnants of broken families and inviting viewers, by turns, to grasp the full weight of these 180 kilos of photographs en masse, and to reflect on the singularity of the faces that peer out from each photo, the installation provides a means, however messy and uncertain, of visually charting these new geographies of kinship.

Lê’s most recent work, Crossing the Farther Shore, further explores the relationships among strangers through its introduction of transcribed oral histories compiled by the Vietnamese American Heritage Foundation (VAHF) and archived at Rice University in Houston, Texas. By uniting writing with photograph, oral memories with visual narratives, Crossing the Farther Shore invites visitors to ponder the processes that bring these elements to relate to each other, even if they do not quite fit together seamlessly or cohesively. Only brief excerpts from oral histories are hand-written onto the verso of select photographs, without crediting the source of the stories told by narrators. Accordingly, the narrators become just as anonymous as the subjects of the orphaned images. These pairings are all the more provocative because the terms of their address are not clear. While this ambiguity is effective in the question of relationship, at the same time it resurrects the ethical issues of Erasure more pressingly; indeed some members of the VAHF have objected to Lê’s use of their stories, and the organization as a whole refused to have any official involvement with the exhibit. Since narrators had signed full releases for the transcripts used in the installation the controversial community response to Lê’s work complicates the issue of the ethical uses of oral history. After all, because these transcripts were posted on a university website, they were publicly available and easily accessible. The problem was that, by including these oral histories, Lê directs the community to speak, sympbolically, to the orphan images. However, it appears that VAHF objected to the terms of this conversation, and sought to distance themselves from Lê’s work, believing that the artist the was a communist sympathizer, on the basis perhaps that he had relocated to Vietnam and had previously included flag of the communist party in his pieces.[30] This incident reveals deep fissures within the diasporic Vietnamese community itself, which, as the work of Thuy Vo Dang shows, is constituted by rigid adherence to a discourse of anticommunism,[31] on the one hand, while, on the other hand, distancing itself from, if it does not censor outright, opposing or even diverse views. These rifts are a reminder of the limits of stranger intimacy.

Fig. 6. Dinh Q. Lê, Crossing the Farther Shore, 2014, courtesy Nash Baker and the Rice Gallery, Houston.

Fig. 6. Dinh Q. Lê, Crossing the Farther Shore, 2014, courtesy Nash Baker and the Rice Gallery, Houston.  Fig. 7. Dinh Q. Lê, detail from Crossing the Farther Shore, 2014, courtesy Nash Baker and the Rice Gallery, Houston.

Fig. 7. Dinh Q. Lê, detail from Crossing the Farther Shore, 2014, courtesy Nash Baker and the Rice Gallery, Houston. Despite this ideological resistance to reclaiming family, Lê’s installation nevertheless offers the clearest expression of a compulsion to collect; this compulsion, as I have shown, is remarkable because it is manifest in a number of projects, initiated by many overseas Vietnamese, which aspire to assemble archives. Indeed, so pronounced is it that it evinces, arguably, an archival desire, a term I invoke for two reasons. First, I deliberately echo the “burning desire” that Geoffrey Batchen contends lies at the heart of photography’s origins.[32] Though Joseph Nicéphore Niépce was the first to voice this sentiment, Batchen shows that because it was felt by many, the origins of photography turn out to be about a single inventor and original patent registered in that storied year of 1839, as history books continue to avow, but rather the fulfillment of a broadly shared longing, the culmination of collective ambitions.

Batchen’s account of the burning desire for photography at its inception in nineteenth-century Europe seems distant from the experiences of the Vietnamese diaspora in the last few decades of the twentieth century, but these archiving projects share collective impulses that find expression through visual form. For these projects, collecting merges into archiving to become more than just method; it emerges as a vital theme in the works.

This task of collecting, this desire for archives, matters when it comes to the Vietnamese diaspora because family photos are either overlooked or have disappeared from official institutions. State archives in Canada and the United States — two of the nations that, per capita, welcomed the greatest numbers of Vietnamese refugees — have only recently begun to collect vernacular artifacts such as family photographs.[33] In Vietnam, where public discussion of the Indochinese refugee crisis is still discouraged, archives focus on documentary photography and emphasize revolutionary struggles; they do not, to my knowledge, contain family photos.

The dearth of vernacular artifacts in institutions is hardly surprising, given the function of national archives as a repository for official state history. Whereas Marita Sturken’s case study of U.S. public memory emphasizes the points of contact between personal memories of family photos and institutions of public history, my research suggests that this intersection is the exception rather than the rule. For the Vietnamese diasporic family, such personal images seldom turn up in the public record. Accordingly, the differences between personal memory and national history can be critical, especially when considered in light of Kwon’s reminder of the importance of the former in posing a direct, if subtle, challenge to the latter. The dearth of vernacular artifacts in national archives, coupled with the destruction and abandonment of family photos, intensifies the Vietnamese diaspora’s archival desire.

Even when other institutions are open to the inclusion of family photos, the personal memories associated with private collections and the official history of national archives should not be merged without attending to their differences. On the one hand, by collecting family photos, these diasporic initiatives compensate for the limits of state archives; on the other hand, the projects offer a critique of the politics of erasure associated with official archives.

This context helps explain the urgency behind digital projects by diasporic artists. Jacqueline Hoang’s digital archive promises to supply these missing pictures, as does Lê’s Erasure. However, the latter does so in a format, which, as the title suggests, is paradoxical, as the preservation of these photographs implies an inevitable disappearance and destruction, especially with respect to their tactile dimensions and the affective resonances of this sense of touch. At the same time, Lê’s title emphasizes how, in the face of loss, a sense of community is established through a collective act of seeking and finding its own images, however difficult they are to recognize, however impossible they are to claim fully, notwithstanding gestures that would disown these images. These archiving projects supplement even as they are shaped in tension with state archives, which are either indifferent or opposed to collecting family photos.

Coda

When I started exploring the role of family photos in mediating the Vietnamese diaspora, these collecting projects seemed to offer intriguing alternatives to the limits imposed by the narrow and pointed ideological interests of national and state archives. However, the relationship between losing photos and finding them may not be as simple as they might appear. I began to grasp just how dense the layers of complexity were during fieldwork inspired in part by Dinh Q. Lê’s work. In the course of my research, I eagerly traced not the trail of visual artifacts churned up in this installation but rather Lê’s very steps through Ho Chi Minh City to one of the rich sources of this compelling work. It led to a street famous for junk and antique shops filled with sundry bric-a-brac: lacquerware, communist kitsch, and photographs. This is where Lê found the snapshots and studio portraits for his installation.

And this is where I found both less and more than I was looking for, in the form of stacks of photos ripped from family albums. The prospect of flipping through thousands of them, portraits of men, women, and children of a bygone era, coiffed, preening, smiling — in search of what and to what end? — was too overwhelming to contemplate. A cursory review confirmed what I suspected: few had any writing or a date. Still, a portion of them, despite this frustrating lack of context, hinted at the reasons for their abandonment. They show men and women wearing the wrong uniform, or who posed with white friends who were likely American, or who had indulged in bourgeois amusements, such as travel to a foreign country. In a nation where display of the flag of the defeated Republic of Vietnam is still a prosecutable offense, it is little wonder that those stained with such signs of misalliance surrendered their photos.

Despite the fascinating secrets suggested in each of these individual images, as a scholar of visual culture I share the preference of galleries and museums for family albums over single photos, for the former’s potential to disclose more historical information, even as I remain wary about the hegemonic function of these national institutions in cases when they do collect albums. A family album is like a personal micro-archive. A collection of albums promises to hold a wealth of historical information. Removed from their albums, photographs lose much of their value, or so I thought.

I wanted to know: What happened to the albums? The shopkeepers explained that no albums existed and that images where already “orphaned” — already torn from their albums and renounced by their families. They insisted that no one sold intact albums.

On my last day in the city, however, I stumbled on a treasure trove: a shop that stored, in its dark display cases, several albums. After I flipped through a few, the owner said she had stacks more at her house, on the outskirts of the city, if I was willing to brave a scooter ride through the snarl of rush-hour traffic. She could read my excitement in my trembling hands. At her house, Mai (not her real name) led me up narrow stairs to her covered rooftop, where they were piled amid rusted lamp bases, dusty pictures of plump American pinups, and junked math exercises. There were dozens of them, some sticky, a few falling apart, others well preserved.

Many were empty, however. It turns out Mai and her husband plunder the albums in response to customers’ demands. (Anticipating that someone like me would come along, they leave some untouched, but they have taken apart most of them.) These customers are, apparently, researchers keen to look at evolving hairstyles, dress styles, and body shapes. They use the photos for histories, expositions, and exhibitions. What they mean for the shopkeepers is a different, though complementary, matter. In savvy response to this demand, they determined that by the piece, the photos are more valuable than they are collected within albums.

Still, I could not help wondering what value photos of anonymous people — of someone else’s family — could have to anyone? When I began my research, I believed the value of photos lay in the connections among them; torn from the context of their albums, the prospect of deciphering the photos’ meaning is daunting, a problem that Lê’s work tackles and seeks to overcome. Then again, perhaps all who are on the hunt, whether to pursue intellectual curiosity, to sate a visual longing, or to collect for the sake of collecting, share one key characteristic. My training directs me to archives, but my brief adventure suggests that sometimes one produces the archives one looks for.

I close with a story that reveals the other side of this search. Although the diaspora’s desires are decipherable, I was surprised, though should not have been, that those who had been left behind, so to speak, had their own desires. On this fruitful trip to Vietnam, I learned that a famous artist paid fifty dollars per kilogram for the photos he used in his installation. Was it Lê? I wondered. I have yet to ask him. But what I know is that this is a reasonable price, when compared to the current market value of American G.I. photo albums on eBay, which is close to three hundred dollars apiece. The business of war memorabilia is booming. By contrast, even though fewer people want Vietnamese albums, demand is sufficient to keep Mai and her fellow shopkeepers busy. For such bulk orders, Mai and her husband spend hours tearing and ripping.

Archival desire, Jacques Derrida reminds us, is a paradox: Reckoning with the losses of the past, it is propelled by a sense of futurity; keen to preserve, it also inevitably destroys.[34] The seeming “triumph” of capitalism represented in the market for memorabilia, however, can also be seen as a rejoinder to the Vietnamese state’s earnest attempts to construct a specific national history,[35] one that disregards the partial visual narratives on display in vintage shops for those who want to look and are willing to pay.

In a forward-looking Vietnam, where locals tend to favor the new over the old, entrepreneurs like Mai make a living feeding the diaspora’s hunger for the discarded, disassembling and reassembling the archives it desires. These savvy entrepreneurs thus fully embrace the spirit of Đổi Mới, or economic renovation, by providing the images the Vietnamese diaspora, and for that matter apparently researchers, want to see. In this manner, the shaping of an archive through the collecting of family photographs also entails the shaping of communities — of diasporic Vietnamese and those entrepreneurs who, it turns out, are not quite left behind, but instead are keen to forge ahead. These are communities entangled around the photographs that they by turns take apart, conjure up, and resignify for one another.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, for their support of this research. My thanks the staff at the Rice Art Gallery who agreed to welcome me, on a day that the Gallery would have been closed, just so that I could see Crossing the Farther Shore in person, and to Linda Ho Peche, who served as Project Manager at the Houston Asian American Archive, for speaking to me about the Vietnamese American community’s mixed responses to this exhibit. I am grateful to Anthony Lee and Sandra Mathews for their expert editorial guidance. For their insightful feedback, I thank Sarah Bassnett, Elspeth Brown, Lily Cho, Deepali Dewan, Donald Goellnicht, Sarah Parsons, and Y-Dang Troeung.

Thy Phu is an Associate Professor at the University of Western Ontario. She is author of Picturing Model Citizens: Civility in Asian American Visual Culture, and co-editor, with Elspeth Brown, of Feeling Photography. Her current research focuses on Vietnamese photography and the American war.

Notes

Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen, Memory Is Another Country: Women of the Vietnamese Diaspora (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2009); Andrew Lam, Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005).

Although the first and second waves of the Vietnamese diaspora have been the primary focus of scholars working in Asian American studies and area studies, critics have begun to consider the significance of other aspects of the diaspora, particularly to nations that were formerly part of the Eastern Communist bloc. See, for example, Christine Schwenkel, “Rethinking Asian Mobilities: Socialist Migration and Postsocialist Repatriation of Vietnamese Contract Workers in East Germany,” in Critical Asian Studies 46.2 (2014): 235–48; and Thang Dao, “Writing Exile: Vietnamese Literature in the Diaspora,” dissertation, University of Southern California, 2012.

For a cogent discussion of the ways this unhappy trinity of award-winning photos from the Vietnam War explicitly raise the specter of Asian violence exacted on Vietnamese bodies, see Sylvia Shin Huey Chong’s The Oriental Obscene: Violence and Racial Fantasies in the Vietnam Era (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

Heonik Kwon, The Other Cold War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009). See also Heonik Kwon, “Cold War in a Vietnamese Community,” in Four Decades On, Scott Laderman and Edwin A. Martin, eds. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 84–102.

Quoted in Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen’s Memory Is Another Country, 20.

See especially Pierre Bourdieu, et al., Photography: A Middle-brow Art (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1990 [1965]), Shaun Whiteside, trans. Julia Hirsch, Family Photographs: Content, Meaning, and Effect (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981); Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997); Jo Spence, Putting Myself in the Picture (Seattle: Cornet Press, 1998); Jo Spence and Patricia Holland, eds., Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography (London: Virago, 1991). However, as Marianne Hirsch is careful to point out, in her contrast between the ideological “gaze” and the individual “look,” the discursive ends of family institutions are contestable.

Joan Schwartz, “The Album, the Art Market, and the Archives.” Paper delivered at the “Collecting and Curating Photographs: Between Private and Public Collections” colloquium, May 3, 2014, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto.

http://pulaubidong.wordpress.com (accessed July 15, 2014).

http://www.jacquelinehoangnguyen.com/The-Making-of-an-Archive (accessed July 15, 2014).

Although as of this writing I have not had the occasion to visit these installations, I have copies of exhibition catalogues, and have discussed the works with the artist during a meeting in Ho Chi Minh City, in January 2012, and over the course of a series of e-mails.

Martha Rosler, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (on documentary photography),” in Martha Rosler: 3 Works (Halifax: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1981).

Exchange, via e-mail, between the author and Michelle Kumata, exhibit director, Wingluke Museum, Seattle, June 26, 2014.

Marianne Hirsch, ed., The Familial Gaze (Hanover, NH, and London: Dartmouth College, 1999).

“Proximate Spectatorship in the Time of Cold War Human Rights.” Paper presented at the “Doing Photography” conference, Durham, UK, January 2013.

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001 [1951]), 297.

For example, the oral histories collected by Carina Hoang contain accounts of orphans who found surrogate siblings and parents in refugee camps. See The Boat People: Personal Stories from the Vietnamese Exodus (Cloverdale, Washington: Beaufort Books, 2013).

See Shawn Michelle Smith, American Archives: Gender, Race, and Class in Visual Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), and Laura Wexler, Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of U.S. Imperialism (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

Yen Le-Espiritu, Body Counts: The Vietnam War and Militarized Refugees (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick draws our attention to the tactile dimensions of affect in Touching Feeling (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003. For a discussion of tactility and affect in relation to photography, see Feeling Photography, Elspeth Brown and Thy Phu, eds. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).

http://www.erasurearchive.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1&Itemid=2 (accessed June 2, 2014).

See, for example, Olive Hoang, “U.S. Copyright Office Orphan Works Inquiry: Finding Homes for the Orphans,” Berkeley Technology Law Journal 21.1 (2014): 265–88.

Tina M. Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

Nayan Shah, Stranger Intimacy: Contesting Race, Sexuality, and the Law in the North American West (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011).

For discussions of adoptions as a Cold War process of subject formation, see, for example, David Eng, The Feeling of Kinship: Queer Liberalism and the Racialization of Intimacy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010); Jodi Kim, Ends of Empire: Asian American Critique and the Cold War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); and Laura Briggs, Somebody’s Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

Alice Toby Volkman, ed., Cultures of Transnational Adoption (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005).

Skype interview with Dinh Q. Lê and author, August 31, 2014. Despite several requests, I was unable to reach anyone at the VAHF for a comment.

Thuy Vo Dang, “The Cultural Work of Anticommunism in the San Diego Vietnamese American Community,” Amerasia Journal 31.2 (2005): 65-85.

Geoffrey Batchen, Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999).

In Toronto, the Art Gallery of Ontario, a publicly funded institution, features The Max Dean Collection, a growing compilation of family albums, the bulk of which are orphaned.

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), translated by Eric Prenowitz.

For more on the politics of memory in Vietnam, see Christina Schwenkel, The American War in Contemporary Vietnam: Transnational Remembrance and Representation (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009).