The Passionist China Collection Photo Archive

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

From 1921 to 1949, eighty Passionist missionaries (priests, brothers, and fathers from the Roman Catholic order of the Passionists of St. Paul of the Cross Province) were sent from the United States to West Hunan, China (Xiangxi 湘西). From 1921 to 1981, the order published The Sign magazine; all of the editors were Passionist priests. By 1931, this American Catholic monthly counted 105,015 subscribers nationwide. Because the first issues coincided with the venture into China, the Passionist leadership quickly realized that the magazine would be the perfect venue to promote evangelization in China, solicit and receive donations, and facilitate communication with American benefactors. Consequently, from 1922 to the early 1950s, when the China mission ended, “With the Passionists in China” was a monthly feature.

It was a popular feature, written by and including photographs from those missionaries.

From the beginning, missionaries “snapped” photos for possible inclusion in the magazine, and eleven of the men became the primary sources for images. All began as amateurs, but some came to exhibit professional attention to detail and composition. In other cases, missionaries used photography as a means of relaxation.[1]

The Passionist China Collection[2] Photo Archive is estimated to consist of six thousand images in diverse media. The digitization process, taking place at the Ricci Institute at the University of San Francisco, began in 2012 and should be completed in 2014. At that point, the physical collection will have a permanent home at the Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Scranton, in Pennsylvania,[3] which serves as the repository for the Passionist Historical Archives of the St. Paul of the Cross Province.[4]

Diversity of Passionist China Collection Photo Archive

Assigned to the China mission from 1921 to 1951, Father Raphael Vance, C.P. (1894–1958), became a skilled and prolific photographer. He and the other missionaries developed a pattern whereby they sent both pictures and text to The Sign editor for publication. They also used the services of professional photographers; figure 1 is representative of approximately one hundred Photo Archive images of this kind. The Passionist China Collection Photo Archive contains photos purchased at shops in Shanghai, Beijing, and Hankou during the thirty-year span of the Passionists’ mission. Whereas some made their way into The Sign, a number were made into vanity postcards, and many, such as the one shown in figure 1, accompanied letters sent home for the enjoyment and education of relatives, friends, and other Passionists.

The Sign used photos in multiple ways. In demand were single images of the author priests and of priests together with Chinese people.

Fig. 2: Fr. Leo Berard, C.P. (left with white hat), Fr. O’Gara (with white hat sitting down) .For trip from Shenchow (Chenzhou 辰洲).

Fig. 2: Fr. Leo Berard, C.P. (left with white hat), Fr. O’Gara (with white hat sitting down) .For trip from Shenchow (Chenzhou 辰洲). Many photos in the Passionist China Collection Photo Archive show missionaries’ interaction with the local people. Here, Father Leo Berard, C.P. (1898–1973), and Father Cuthbert O’Gara (1886–1968) are dressed in lay garb as they pose with Chinese citizens as well as the porters, and donkeys, who will assist them on their journey.

Typical archive photos portray the daily rituals of Chinese life, as well as street scenes and the countryside. Of great interest were the photographs of missionary buildings, chapels, ministry sites, and Chinese congregations, and particularly the photos of missionaries with local and national military and political leaders and Catholic officials.

This photo, from the late 1920s or early 1930s, is typical. In it orphan children were posed for a Sign magazine appeal in order to bring about awareness and to solicit support and sympathy for the West Hunan mission. In the foreground you can see the shadow cast by the photographer.

Although most missionaries and the editors praised the value of the “With the Passionists” series, archival documentation reveals that pictures selected to accompany the articles occasionally created false impressions of life in China. At times, the missionaries in the field thought that the editors did not always provide an accurate understanding of Chinese society.

Pictures of Passionist priests with the American Catholic sisters and their Chinese parishioners reinforced the missionaries’ strong connection with subscribers back in the United States. Images in The Sign personalized their experiences in a public way. This was directly tied to fund-raising. Photos of orphan children were quite popular, as they indicated how donors’ money was being used.

Fig. 5: In the Sisters compound, Shenchow; Sisters of St. Joseph (black veil white front), Sisters of Charity (square shaped headgear), Chinese children, adult, Chenzhou, Bishop O’Gara (center), Fr. Paul Ubinger, C.P. (left), 1930s.

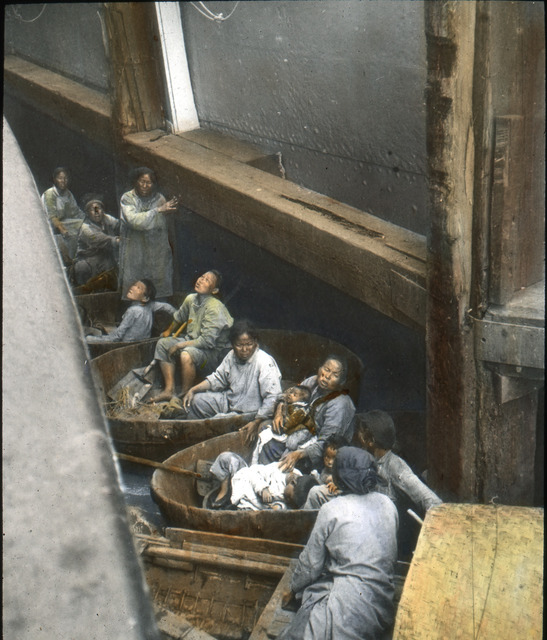

Fig. 5: In the Sisters compound, Shenchow; Sisters of St. Joseph (black veil white front), Sisters of Charity (square shaped headgear), Chinese children, adult, Chenzhou, Bishop O’Gara (center), Fr. Paul Ubinger, C.P. (left), 1930s.  Fig. 6: Jardine Estate. Chinese families in sampans with all they have in the world. Hankou flood, 1931.

Fig. 6: Jardine Estate. Chinese families in sampans with all they have in the world. Hankou flood, 1931. Figure 6 demonstrates that disasters and social events attracted the attention of the missionary photographers. By 1923 the Passionists had decided to set up their financial operations in Hankou in the old Jardine Matheson Estate. During the 1931 flood their property was devastated.

Passionist China Collection Slides

Fig. 7: Original caption: “In the courtyard of larger temples one may meet a pagan priest, a bonze such as the one here shown. He stands beside a cast-iron incense burner that has stood untouched in the moral and social upheaval that goes on year after year”.

Fig. 7: Original caption: “In the courtyard of larger temples one may meet a pagan priest, a bonze such as the one here shown. He stands beside a cast-iron incense burner that has stood untouched in the moral and social upheaval that goes on year after year”. The more than one hundred hand-colored glass lantern slides in the collection provide another intriguing source of information, a perspective on missionary interaction with the environment and diverse segments of Chinese society distinct from what one may glean from black-and-white photos. The slides were used when missionaries gave public lectures to Catholic audiences in the United States. Note cards from the period indicate the probable caption for figure 7, a reflection of attitudes of the time.

Other records are clear that when Passionists sent photos to the United States, they were professionally colored by Edward Van Altena Studio, in New York City. Figure 8 was originally a professional, black-and-white professional photograph purchased by the Passionists in the 1920s. Like figure 7, it made the rounds on the lecture circuit.

Fig. 8. Professionally colored by Edward Van Altena Studio in New York City. Figure 8 was originally a black and white professional photograph purchased by the Passionists in the 1920s, from Mactavish & Co., LTD, Shanghai.

Fig. 8. Professionally colored by Edward Van Altena Studio in New York City. Figure 8 was originally a black and white professional photograph purchased by the Passionists in the 1920s, from Mactavish & Co., LTD, Shanghai. Promotional Pamphlets and Brochures

From 1926 to 1950, for educational and fund-raising purposes, several Sign articles were reprinted with the addition of special photos and commentary. For example, in the Passionist China Collection is a pamphlet entitled For Christ in China (1926), which was used to raise funds in conjunction with the 1926 West Hunan famine.

In 1929 Passionist Fathers Walter Coveyou, Godfrey Holbein, and Clement Seybold were murdered by bandits. This was a major disruption of diplomatic relations among the United States, China, and the Vatican. Photos of the three priests were included in Eyes East, a promotional booklet published in 1930. Because the pamphlet was so popular, two editions of Eyes East: On Chinese Pathways with the Passionist Missionaries followed the next year, both also incorporating the photo collage.

In the mid-1930s, Boys Town in China, by Father Harold Travers, C.P. (1899–1984), used photos that highlighted the orphanage for boys in Paotsing (Baojing 保靖), Hunan. Instead of using missionaries’ images in the 1942 booklet The Passionists in China, rationing and restrictions during World War II necessitated that editor Father Ronald Norris, C.P. (1900–1973), purchase numerous professional photos for it. The booklet was printed in the United States, and distributed to promote the needs of the West Hunan mission.

Here we see how photos were used for public relations just before the Communists moved into West Hunan. The Passionists and Sisters of Charity dedicated their mission hospital in 1949. The next year, Your Yuanling Catholic Hospital provided benefactors with a description of what patient care entailed and requested funding for training of Chinese nurses. At the time, there was hope among the Passionists for a new China; by 1955, all the Passionists had been expelled.

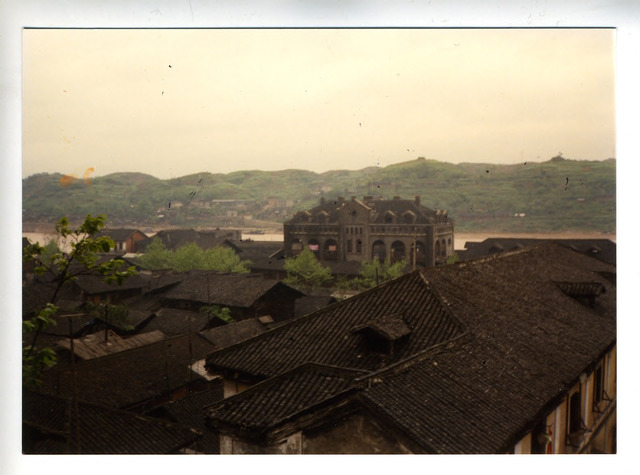

Fig. 11: A view of former Yuanling 沅陵 Catholic Hospital and Yuan River in the background, Yuanling, West Hunan, April 1989.

Fig. 11: A view of former Yuanling 沅陵 Catholic Hospital and Yuan River in the background, Yuanling, West Hunan, April 1989. In contrast, this is a view of Yuanling 沅陵 Catholic Hospital in 1989, forty years after it had been dedicated. In the background is the Yuan River. This is one of the approximately 400 color slides I took to document my own travels in West Hunan, Wuhan, Changsha, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangzhou, and Hong Kong in 1989. These slides reveal the changes that had taken place since missionaries took their photos, in the 1920s to the 1950s.

Passionist China Collection Scrapbooks and Film

There are at least five scrapbooks in the Passionist China Collection. Photos were collected by the missionaries and their families for individual use and interpretation. They present images of Shanghai, Hankou, Beijing, and West Hunan from the 1920s to the 1950s. In addition, some filmmaking was done by missionaries on a limited basis during the 1930s and 1940s.

Passionist China Collection Photo Archive Research Opportunities

Travel grants are available for scholars who would like to use the photo archive during the digitization process, which will continue into the fall of 2014 at the Ricci Institute. When that project is complete, there will be additional grants available for those who would like to study the collection.

In retrospect, the Passionist missionaries who took these photos provide more than religious narrative. In fact, these images are a compelling reflection of Hunan’s history. They are visual records of twentieth-century Chinese ethnicity, society, the environment, agriculture, gender relations, banditry, local power relations, and economics. They bring to life the prose and cultural legacy that have given prominence to the Hunan novelists Shen Congwen 沈从文 (1902–1988) and Peng Xueming 彭学明 (1964–). The collection is also a resource for studying the dynamics of Chinese–Western cultural exchange as it applied to philanthropy, business, war relief, and understanding the parameters of practice and change pertaining to Chinese Catholicism during the period when Passionists were in residence in China.

Father Robert E. Carbonneau, C.P., is a Passionist priest who has been working, in collaboration with the Ricci Institute at the University of San Francisco, to digitize the Passionist China Collection Photography Archive and make it available to scholars since 2012.

Notes

Most Passionists who took their first photos in the 1920s continued into the late 1930s. The ones who did were Brother Lambert Budde; and Fathers Basil Bauer, Theophane Maguire, Flavian Mullins, Cuthbert O’Gara, Cormac Shanahan, Raphael Vance, and Antoine DeGroeve. In the 1940s, Fathers Caspar Caulfield, Wendelin Moore, and Leonard Amrhein were active.

You will find a general summary of the Passionist China Collection at http://riccilibrary.usfca.edu/view.aspx?catalogID=16486.

For more on Special Collections, visit http://www.scranton.edu/academics/wml/bk-manuscripts/index.shtml.

This relationship began in 2012 when the archives moved out of Union City, New Jersey. For background on PHA, see http://www.cpprovince.org/archives/.