Kon Michiko—New Work

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

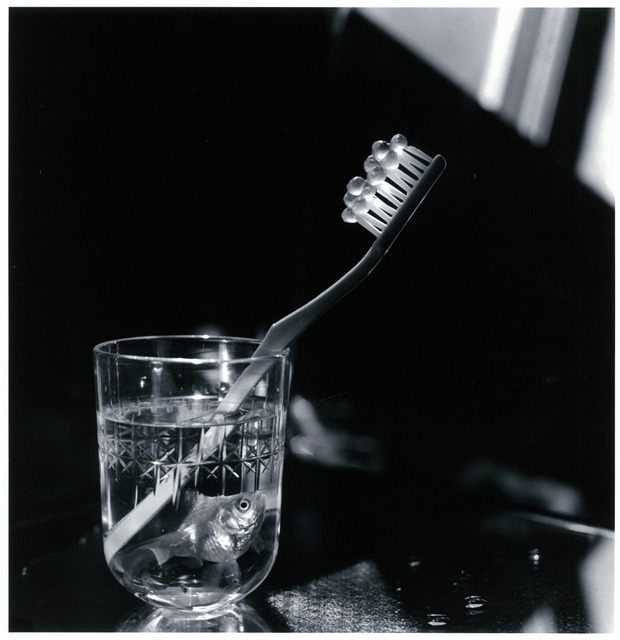

Fig. 1. Kon Michiko, Goldfish, Salmon Roe, and Toothbrush, 1985, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

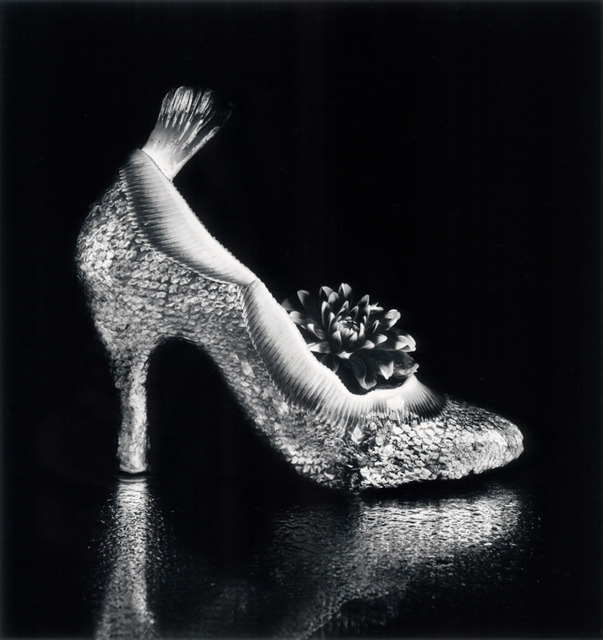

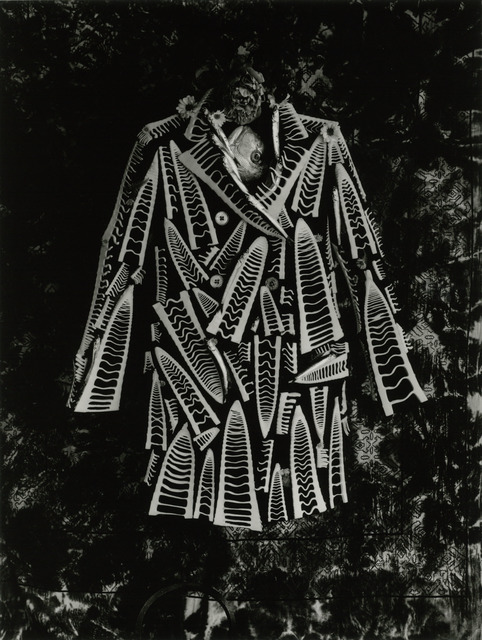

Fig. 1. Kon Michiko, Goldfish, Salmon Roe, and Toothbrush, 1985, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Kon Michiko’s surreal still lifes are unlike any other photographs. At first glance they appear to be mundane objects—a toothbrush in a glass (fig. 1), a high-heel shoe (fig. 2), a designer coat (fig. 3). Only on closer examination does the viewer realize that salmon roe have been impaled on the toothbrush bristles and a goldfish swims in the glass; that the surface of the shoe has been crafted from salmon skin and flounder fins; that the coat is made up of bamboo shoots and fish parts and a fish head lurks inside the collar. Kon’s work is simultaneously seductively beautiful and shockingly disturbing. What is certain is that viewers never forget their initial encounter with one of her images.

Fig. 2. Kon Michiko, Salmon, Flatfish, and High Heel, 1987, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 2. Kon Michiko, Salmon, Flatfish, and High Heel, 1987, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.  Fig. 3. Kon Michiko, Bamboo Shoot Coat, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 3. Kon Michiko, Bamboo Shoot Coat, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Kon first studied painting and printmaking in art school and turned to photography only in the late 1970s, when she began making collages. She spent two years at Tokyo Photographic College and held her first solo exhibition, Still Life, at the Shinjuku Nikon Salon in Tokyo in 1985. She was soon recognized as one of the most innovative photographers working in Japan; she was the recipient of the prestigious Kimura Ihee Prize in 1991. Her first exhibition in the United States was held at the List Visual Arts Center at MIT in 1992. Her work was also included in the History of Japanese Photography exhibition organized by Anne Tucker at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 2003. Since 1990 she has been exhibiting at Photo Gallery International in Tokyo. An exhibition of her new work in early 2014 - the first in more than ten years - offers an ideal opportunity to assess Kon’s career.

Fig. 4. Kon Michiko, Cabbages and Bed #2, 1979, © Kon Michiko, 1979, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 4. Kon Michiko, Cabbages and Bed #2, 1979, © Kon Michiko, 1979, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Kon’s earliest published photographs, from the late 1970s, point at the direction her work from the 1980s and 1990s would take. In Cabbages + Bed # 2 (fig. 4), from 1979, more than thirty cabbages, some dark, some light, lie scattered over a bed. The heads are lit such that they resemble cloth as much as vegetables, and the viewer is further confounded by the impression in the pillow that mirrors the forms of the leaves.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Kon began making photographs of objects, most of which are familiar things she assembled from daily life, such as fish, vegetables, and other foodstuffs; flowers; and insects. These objects held and continue to hold a special fascination for Kon:

There are sea and mountains in the town where I have been living since my birth. We can get fresh fish and vegetables there. When I look at them or make food from them, more than having an awareness that they are foodstuffs, I feel the delicacy and beauty of their forms, the eroticism of raw things, as well as their transience. I combine those foodstuffs with my favorite antiques, clothes, and shoes and other things. I studied painting and printing (lithography and silk screen). However, giving expression to a surrealistic world through photographs is for me a far more provocative exercise than painting on paper. I make notes of what captures my attention in everyday life, and subsequently I make sketches of those things that grow in my imagination. Then I gather materials and make the objects that I will photograph.

Fig. 5. Kon Michiko, Cuttlefish and Sneaker, 1989, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 5. Kon Michiko, Cuttlefish and Sneaker, 1989, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Many of the objects she photographed during this period took as their model the luxury goods favored by wealthy Japanese during the height of the Bubble Economy—high-heel shoes and high-top sneakers (fig. 5), fedora hats and melons that even today sell for exorbitantly high prices on the streets of Tokyo. By creating them from fish and other living things eaten daily by the residents of the city, Kon seems to be commenting on the intense consumer culture of modern urban Japan.

In a recent conversation, however, Kon expressed some reservations with this interpretation:

I didn’t know that my work is interpreted that way in the West. How my work is interpreted is up to the individual, so I cannot say if one interpretation of my work is correct or incorrect. I think it may be partly correct, but it is not a description that I favor. When I went to the Tsukiji Market in Tokyo and saw great amounts of fish, I had the experience of being surprised anew to know that we were living by consuming so much seafood. I have found various meanings in my work—feelings of atonement since human beings in their need to live take lives even if they do not do so themselves; feelings that I have, wanting to bring things back to life by making objects and taking photographs; feelings of wanting to memorialize. I suspect that there are many other ways to interpret them, but my motivation in making these objects lies in the fascination I have with the beauty of things that are passing out of existence.

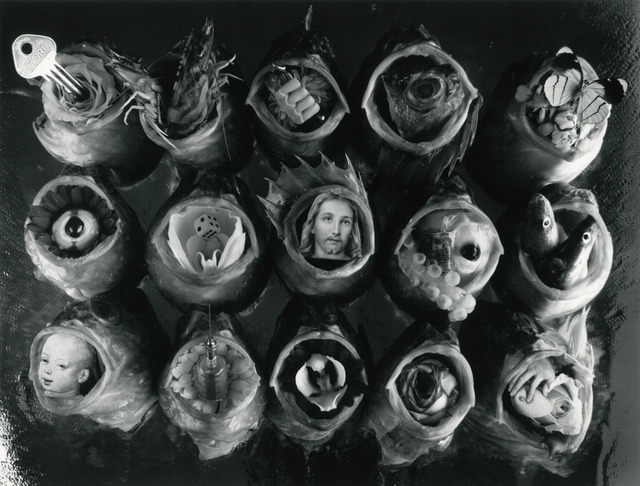

Fig. 6. Kon Michiko, Scorpionfish Mouths, 1994, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 6. Kon Michiko, Scorpionfish Mouths, 1994, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Other work from this period juxtaposes the unexpected—the mouths of scorpion fish holding an image of the head of Christ, a die inside an orchid, a syringe extending from a flower (fig. 6). In each work Kon draws on her powerful imagination to create a tension between the real and the imagined, subtly manipulating the perceptions of her viewers.

Kon took time off from making photographs to take care of her aging mother, a decision for which she has no regrets.

It was when I was five years old that I learned that people die. I remember vividly that I said to my mother, who was preparing dinner in the kitchen, that I would die if she died. My mother was smiling at me, but it was the greatest fear for me as a little girl to know that the bodies of the people I loved would disappear from the earth, even if heaven exists. I don’t know why but I have had intense feelings about life and death since my childhood. I forgot about them when I became an adult, but they remain somewhere in my heart as a black dot. As I watched my mother growing old, becoming afflicted with dementia and gradually declining, I felt I wanted to escape. However, instead, I used my time to take care of her since it was she who had always given me freedom and time to produce my art works. I think it was a necessary time for me. Some people made comments about my not producing photographs over the past ten years or so, but it did not seem such a long time to me. I did not feel any stress when I did not make photographs.

Fig. 7. Kon Michiko, Metronome and "Hachi", 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 7. Kon Michiko, Metronome and "Hachi", 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Over the past two years, Kon has returned to making photographs. Much of her new work uses antiques, dolls, and Japanese objects that were not present in her earlier work as well as photographs of family members and her pet dog (fig. 7). As in the past, her photographs make stark comments on life and death. Through her meticulous silver gelatin prints, she imbues fish and insects and flowers with new life.

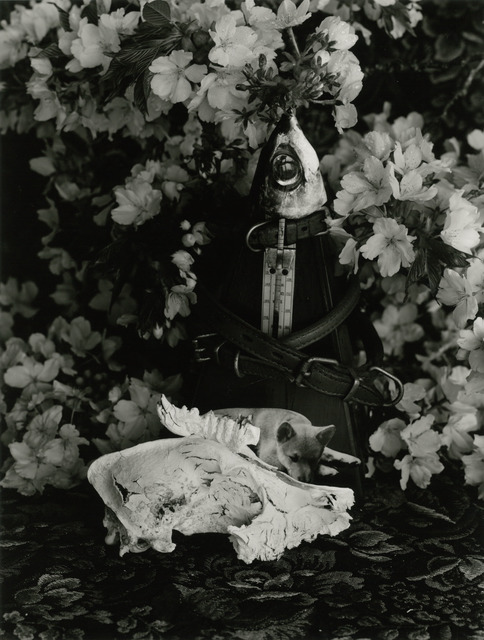

Fig. 8. Kon Michiko, Halfbeak Kabuto, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 8. Kon Michiko, Halfbeak Kabuto, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.  Fig. 9. Kon Michiko, Dresser in a Pond, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 9. Kon Michiko, Dresser in a Pond, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Her newfound interest in traditional Japanese objects is best represented by Halfbeak Kabuto (fig. 8). In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, samurai warriors would ornament their battle helmets with various objects to provide symbolic protection or to intimidate their opponents. Drawing on that practice, Kon has placed an arrangement of fish heads and a spiny lobster at the top of a helmet (kabuto) and a fan of halfbeaks spreads out behind them. Dresser in a Pond (fig. 9) brings together objects that one might find in a woman’s vanity—perfume, lipstick, rings, and a razor—with fish, insects, flowers, and figs, creating what is best described as a cabinet of curiosities of Kon’s active imagination.

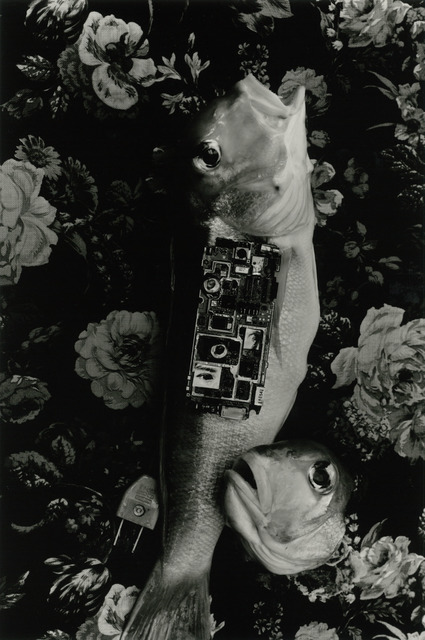

Fig. 10. Kon Michiko, Sea Bream and Rare Metal, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

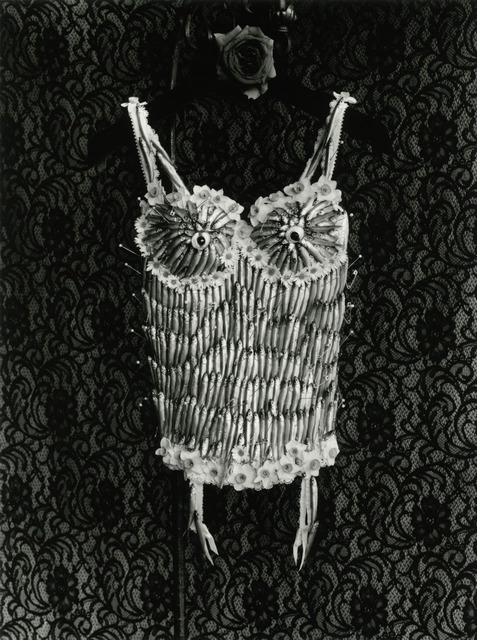

Fig. 10. Kon Michiko, Sea Bream and Rare Metal, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.  Fig. 11. Kon Michiko, Surf Smelt Bustier, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

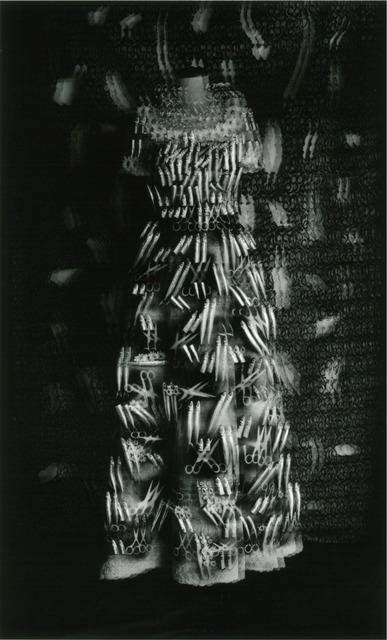

Fig. 11. Kon Michiko, Surf Smelt Bustier, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Although Kon continues to reject the idea that her photographs are comments on the disposable nature of contemporary culture, the stark juxtaposition of a whole sea bream and a discarded circuit board ornamented with fragmentary photographs and fish eyes in Sea Bream and Rare Metal (fig. 10) seems to indicate the opposite. Bamboo Shoot Coat, Surf Smelt Bustier (fig. 11), and Dizzy Dress (fig. 12), like much of her earlier work, seem to make reference to a society obsessed with the latest trends.

Kon demurs when it is mentioned that much of her new work is substantially different from the images she made fifteen and twenty years ago, but she does acknowledge that she possesses a new freedom:

Basically I do not believe that the materials I use have changed; and I think there is not much difference between my old work and new work. Since the parents who made me are no longer here, I feel a freedom, as if I have been liberated and as if frightening things have disappeared. Also, I have become able to think about my work in a more enjoyable way than before. I feel time advances together with me.

In writing about her most recent exhibition, Kon noted, “Since I was a child words such as god, flesh, life, death, and time held for me beauty, horror, and mystery’” and that “through making my work I am able to find my own meanings for these words.”

Kon’s vision remains unique and powerful. She is still able to captivate her viewers.

Fig. 12. Kon Michiko, Dizzy Dress, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo.

Fig. 12. Kon Michiko, Dizzy Dress, 2013, © Kon Michiko, courtesy Photography Gallery International, Tokyo. Samuel C. Morse is Howard M. and Martha P. Mitchell Professor, Art and the History of Art and Asian Languages and Civilizations at Amherst College. A prolific writer on Japanese art, Morse curated, in 2012, the exhibition "Reinventing Tokyo: Japan's Largest City in the Artistic Imagination" at the Mead Art Museum, and edited the accompanying book.

Acknowledgments

Kon Michiko graciously agreed to meet with me in Tokyo last June to talk about her work. Yamada Akiko, formerly of Photo Gallery International, generously asked Kon questions that I had prepared, transcribed them into Japanese, and provided English-language translations. The passages in this article are my adaptations of Ms. Yamada’s original. Takahashi Sayaka, director of Photo Gallery International, provided the images.