The Development of Photo Studios in Korea[1], by Lee Kyungmin

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

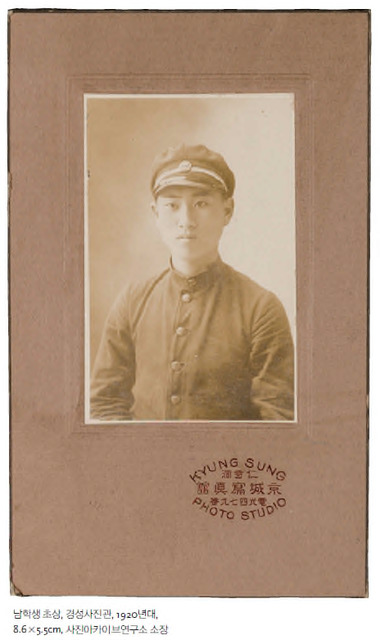

Portrait of a Man, Gyeongseong (Kyung Sung) Photo Studio, ca. 1920s, 8.6x5.5cm. Courtesy of the Research Center of Photography Archive, Korea

Portrait of a Man, Gyeongseong (Kyung Sung) Photo Studio, ca. 1920s, 8.6x5.5cm. Courtesy of the Research Center of Photography Archive, KoreaThis article is about the early history of photo studios in Korea, from the late nineteenth century into the Japanese colonial period (1910-45), including a photo studio exclusively for women. Photography gained popularity slowly following its introduction in the late 1880s, despite misunderstanding and backlash. Rumors and superstitions about the new technology abounded.

Photo studios played a crucial role in making photography a part of popular culture, becoming centers of visual culture where various images of Joseon were produced and circulated.[2] This article aims to illustrate how photo studios were established and what kind of events they encountered. By exploring newspapers of the time, I will attempt to draw a map of modern photographic culture in Korea.

Establishment of Photo Studios

The History of Gyeongseong’s Development published in 1912 by the Association of Japanese Residents in Gyeongseong recounts the story of the Japanese settled in Gyeongseong and the growth of their community.[3] Of note to our discussion is that the book presents statistics on the number of Japanese in Gyeongseong from 1893 to 1911 according to their profession. In the photography business, there were two in 1893; three in 1896; two in 1898; five in 1902; fifty-one in 1909; fifty-one in 1911. This makes it clear that the number of photographers increased dramatically from the period of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) to 1910, when Japan colonized Korea, attesting to the increasing demand for photography following Japanese immigration to Geyongseong.

The photographers and photo studios indicated only as numbers in The History of Gyeongseong’s Development can be identified in newspapers such as Tongnip Sinmun (The Independent), Jeguk Sinmun (Empire News), Hwangseong Sinmun (Imperial Capital Gazette), and Deahan Maeil Sinbo (The Korea Daily News). Photo studios set out to advertise in newspapers around 1900.

Please note that we offer three pieces of photographs in a set instead of four due to the increase in price this year. Saengyeong’gwan (生影館) Okcheondang (玉川堂) in Jingoge.[4]

This advertisement, by Saengyeong’gwan Okcheondang, a studio located in Jingoge (present-day Chungmuro, Seoul), gives notice to customers of its new policy to decrease the amount of photographs in a set. Okcheondang was a photo studio that Fujita Shōzaburō opened around 1889 in Ho-dong near Mt. Nam, and then moved to Yongsan in 1909. Given that Saengyeong’gwan is said to be a photo studio of Murakami Kojirō located in Ju-dong (around Waeseongdae in Mt. Nam), Saengyeong’gwan in the advertisement above seems to be another designation of a photo studio (usually called Sajin’gwan) at the time.

After the printing of this advertisement, various photo studios began to promote their services as charging reasonable prices and offering technological superiority. Among them were Bongseon’gwan, another photo studio of Murakami in Na-dong of Mt. Nam; Gukjoen Photo Studio of Kikuta Shin in Gwangtongbang Mogyo; and Hannyang Photo Studio of Takahashi Tsunesaburō in Gyo-dong.[5]

Most were owned by Japanese, but the establishment of Cheonnyeondang Photo Studio in 1907 was a turning point in the history of photo studios in Korea.

We opened Cheonnyeondang Sajin’gwan in a garden of Kim Gyu-jin’s guest house in Seokjeong-dong under Hwangdan (皇壇), and provide various photography services at low prices. Please make a visit to our studio when you want to be photographed. Kim Gyu-jin and Park Wi-jin, the owners of the photo studio.[6]

The Cheonnyeondang photo studio, which Kim Gyu-jin, a calligrapher, opened in his backyard, was considered unprecedented, and a number of newspapers carried stories relating every detail. For instance, Deahan Maeil Sinbo delivered news about its technology, purchase of equipment, a donation to Gyeongseong orphanage, its expansion and relocation, its credit customers and the non-payment which led eventually to the closing of the studio.[7]

After the opening of Kim Gyu-jin’s Cheonnyeondang, the number of photo studios run by Koreans began to increase, and there were even some outside of Gyeongseong, —for example, Kim Yeong-seon’s Giseong photo studio, in Pyongyang; and O Gyeong-ok’s studio, in Kaesong. The emergence of Korean photographers led to the foundation of the Association of Photographers in Gyeongseong in 1926, demarcating a full-fledged period of photography business.

A Photo Studio for Women and by Women

Korean women found it particularly uncomfortable to expose their face to a photographer, as in traditionally Confucian Korean society they were supposed to veil themselves with a long hood, called ‘jang’ot’ or ‘sseugaechima’, whenever they went out. To attract women clients, this meant that studios had to employ a female photographer or establish a studio exclusively for women in order. The following ad, published in 1903 by Saengyeong’gwan (a studio the Japanese photographer Iwata Kanae took over from Murakami), affirms that a female photographer had been employed to serve women customers.

We have new large equipment. Please visit our studio. For women clients, we have a female photographer. From Iwata Kanae, a photographer of Saengyeong’gwan under Mt. Nam.[8]

Kim Gyu-jin, the owner of the Cheonnyeondang Photo Studio, established, from the beginning, separate studios for women and men, assigning a woman photographer to female customers. In fact, he had to expand his shop to accommodate the increasing numbers.

It is noted that Kim Gyu-jin, the former chamberlain, opened Cheonnyeondang sajin’gwan. The price is cheap and the work is exquisite. Moreover, they have a separate studio for madams and gentlemen and a woman photographing women. The studio is said to be expanding its establishment since more and more madams and gentlemen are visiting.[9]

And:

The news was published on the establishment and expansion of Cheonnyeondang sajin’gwan of Kim Gyu-jin in the previous edition. It is said that the number of customers reached a thousand during the Lunar New Year’s first month, overwhelming the studio with excessive work.[10]

The fact that thousand customers had their photographs taken in Cheonnyeondang photo studio during the first month of the Lunar New Year in 1908 reveals that it was common to have souvenir photographs taken for family and friends as a way to mark the new year. This practice led to the increasing popularity of photography.

Even though the presence of women photographers is established in articles on Cheonnyeondang photo studio and Saengyeong studio, nothing is known of their names or careers. Until the 1910s, women were not acknowledged as producers and consumers of visual culture, including photography. In the early 1920s, however, a female photographer entered the realm of representation. During this decade, there was a change in the way women were seen within society. New categories emerged — New Women (Sinnyeoseong), Working Women (Jigeobyeoseong), and Modern Girls, quite a change from Women (Yeoja), Madames (Buin), and Ladies (Bunyeoja). The new categories show that women began to gain a social status, working outside of the home.

Ms. Yi Hong-gyeong, of 75 Gwancheol-dong, Gyeongseong-bu, starts her photography business on the 21st. She studied the techniques of photography for three years at home, and finally gained the skill to make an exquisite portrait. The lens she uses is a famous Zeiss, and Ms. Yi is the first to open a photo studio for women in Gyeongseong.[11]

Yi Hong-gyeong had studied photography since around 1919, and began a career as a photographer in 1921, when she opened Buin Photo Studio, the first photo studio in Gyeongseong that was exclusively for women. In 1927 she was introduced as a woman photographer in a series of articles titled “Various Occupations of Women” in The Choson Ilbo; she was teaching in the first department of photography for women in Geunhwa Girls’ School, located in Anguk-dong. Women gained access to education and the practice of photography, as teachers and students, throughout the 1920s.

Social History of Photo Studios

Photo studios did not escape the hardships evoked by the Japanese colonial powers. One day in 1928, at five in the morning, Special Higher Police officers from Seodaemun police station raided Gyeongseong photo studio in Insa-dong and Dongyang photo studio in Gwancheol-dong, and arrested six employees including Chae Sang-muk, the owner, from the former and two from the latter. They then conducted an intense interrogation in order to find some vocational school students who were involved in distributing certain documents.

A squad of detectives from the Seodaemun police station suddenly searched through Gyeongseong photo studio in Insa-dong and arrested all its employees, then went to Dongyang photo studio, located across Umigwan, and arrested one there.[12]

Those who were arrested were soon set free, but this event had such an effect on the Korean community that it was covered in all the major dailies, including The Dong-a Ilbo, The Choson Ilbo, and The Jungoe Ilbo. The details are not known, but the Japanese police seemed to target the Korean photo studios as a warning. In fact, the studios, placed under continuous surveillance, were prey to investigations in that they were thought to be good places for suspects to hide.

In addition, photographic equipment was sought after by thieves as it consisted of luxury items, mostly imported from abroad. Cameras and lenses were the main targets as burglars often broke into a studio or smashed a glass show window to steal the cameras on display. Some items were valued under one hundred won while others were worth more than two hundred and three hundred won (a Leica camera, made in Germany, was the most expensive: at the time perhaps a thousand won). Stolen goods were handled through pawnshops or resold to other dealers of photography equipment. Considering that a sack of rice (weighing some hundred and seventy-five pounds) cost around five won at the time, the price of photographic equipment was enormous.

Around noon on the 4th, Han Yeong-ki (27 years old), born in Gwangju-gun, Gyeonggi-do, with three previous convictions but no information on his current address, came under rigorous investigation. He broke into Tong’gu Sajin’gwan and stole a 270-won lens. He was arrested as an officer found that he pawned it and spent all the money on pleasures and entertainment. It seems that he has several other convictions.[13]

The theft of photographic equipment went on throughout the country, in such cities as Daegu, Busan and Jinnampo, not just from studios, but also from businesses that sold the equipment. As newspaper reported on one theft, a man coveted a camera and found a job in a photo studio to get it. Kim Jeong-seok, age twenty-one, of Sohwa photo studio, stole a seventy won camera and a bicycle, taking advantage of a chance to take a picture outside.[14]

Events greater losses were incurred from fire and natural disasters. In particular, hail did serious damage to a number of studios, because most of them, before artificial lighting was in widespread use, had a glass window on the roof. The window allowed the daylight to compensate for the dry plate’s low sensitivity to light. Newspapers frequently reported on the studios’ broken glass caused by hail.

In addition to lightning damage, many places seem to be damaged by hail. Earthenware crocks were broken while glass windows were shattered in school and glass roofs were damaged in photo studio. Some houses in Insa-dong were flooded.[15]

And:

The extent of damage from the hail, which started in Geyongseong on the 30th, is not known, but its scope has been the greatest in Gyeongseong since the establishment of the weather bureau ... these were the largest pieces of hail after the ones the size of beans in 6th and 9th years of Taishō. A number of windows in downtown were damaged, and glass roofs in photo studios shattered.[16]

It was fire, however, that dealt the fatal blow to photography businesses. The cause was usually a short circuit or fire from a charcoal stove, and often the damage was total, with a loss of several thousand won. The scope of damage from fire was so great that studio owners considered insurance a necessity.

(Pyongyang): Around 8:40 p.m. on the 27th the fire started on the second floor in the house of Kuroki Jūni, and burned half the house. It was extinguished around 9:10, but it had destroyed all the equipment, including photographic devices. The damage was estimated at around 7,000 won and the cause was a short circuit. The owner had insurance of 1,000 won.[17]

At the time, photo studios used a charcoal stove to dry photographic paper quickly, and when it overheated, the fire easily leapt out onto the paper, a background screen made of cloth, or the ceiling. A fire caused by a stove damaged Yeoja photo studio, in Jinju; Samseong photo studio, in Pyongyang; and Pyeonghwa photo studio, in Hwanghae-do.[18]

The increase in accidents and damages had to do with the increase in the number of photo studios. In 1930 there were more than a thousand photographers throughout the country; there were three hundred and forty in Gyeongseong alone. These statistics reveals that the business of photography hit its stride, demarcating an era of endless competition for photographers. Korean owners came up with a variety of strategies to keep up with rival Japanese photo studios. In addition to using excellent techniques and providing outstanding services, they promoted their businesses in newspaper advertisements, offered discounts, and hosted or sponsored sporting events. Those in the business banded together in a mutually beneficial association and held exhibits of their work. All of these efforts continued until the end of the boom, when the import of photographic materials was severely curtailed by rationing during the Pacific War.

In 1942, during the peak of the war, the first meeting of the Joseon Photography Association was held in the main hall of Bumin’gwan, in Gyeongseong.[19] The association had been established by domestic commercial photographers with a patriotic purpose, at a time when colonialism cast a long shadow over photo studios.

Jeehey is a PhD candidate at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. She is currently writing her dissertation on funerary photo-portraiture in East Asia.

Glossary of Korean and Japanese Names in the Text

- Names of Photo Studios

- Saengyeong’gwan (生影館)

- Okcheondang (玉川堂)

- Cheonnyeondang (天然當)

- Names of Korean Photographers

- Kim Gyu-jin (김규진; 金奎鎭)

- Yi Hong-gyeong (이홍경; 李弘敬)

- Names of Japanese Photographers

- Murakami Kojirō (村上幸次郞)

- Kikuta Shin (菊田眞)

- Takahashi Tsunesaburō (高橋常三郎)

- Iwata Kanae (岩田鼎)

- Fujita Shōzaburō (藤田庄三郎)

- Names of Photography Associations

- Association of Photographers in Gyeongseong (경성사진사협회; 京城寫眞師協會)

- Joseon Photography Association (조선사진협회; 朝鮮寫眞協會)

Notes

Dr. Lee Kyungmin wrote his dissertation on modern photography in Korea, and is Director of the Research Center of Photography Archives in Korea. He has organized several exhibitions on photography, and has written seminal books on the history of photography in Korea, including Jegugui renjeu (제국의 렌즈; Lens of Empire) and Gyeongseong, Sajine Bakhida: Sajineuro Ingneun Hanguk Geundae Munhwasa (경성, 사진에 박히다: 사진으로 읽는 한국 근대 문화사; Seoul during the Japanese Colonial Period, Taken in Pictures: Modern Cultural History of Korea through Photography). Lee has directed the Seoul Photo Festival in 2012 and 2013. See http://www.seoulphotofestival.com/2013. See also Gyewon Kim’s article on one of the exhibitions organized by Lee, “Unpacking the Archive: Ichthyology, Photography, and the Archival Record in Japan and Korea,” in Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, Vol. 18, no. 1 (2010): 51-88.

For the language transcriptions, I followed the Revised Romanization system for Korean and the Revised Hepburn system for Japanese, with the exception of the names of places where the customary form of transliteration is adopted, e.g. Pyongyang, not Pyeongyang. In all personal names for those from East Asia, the family name comes before the given name. In the case of Korean names, the two syllables of the given name are linked where appropriate, the family name coming first, e.g. Hong Gil-dong, not Hong Gil Dong. The exception is when the author transcribes his or her name in English. The translator is grateful to Lee Kyungmin and the editors of Trans Asian Photography Review.

Joseon is the name of Korea from 1392 to 1897. King Gojong proclaimed the Korean Empire in 1897. However, after the annexation by Japan in 1910, Joseon was used as a general designation to the Korean peninsula. (translator’s note)

Gyeongseong (京城) was the name of the capital of Korea during the Japanese colonial period; it is known today as Seoul. (translator’s note)

Tongnip sinmun, January 6, 1899. This is the earliest advertisement for a photo studio in the country.

You may see the ads in the following newspapers: Jeguk Sinmun, May 6, 1899 and October 9, 1909; Tongnip sinmun, December 4, 1899; Hwangseong Sinmun, December 15, 1900, December 6, 1901, January 7, 1902, February 24, 1902, and March 18, 1902.

“Sajin'gwan gaeeob Cheonnyeondang (Cheonnyeondang, Photo Studio Opened),” Deahan Maeil Sinbo, August 17, 1907.

You may refer to the following articles in Deahan Maeil Sinbo. “Sajin'gwan Igeon (寫眞館移建; Relocation of Photo Studio),” March 24, 1908; “Pyejijigyeong (폐지지경; On the Brink of Bankruptcy),” June 29, 1909; “Gapeul Geosiji (갚을 것이지; Should Have Paid Off),” September 1, 1909; “Misullyeongeop (미술영업; Art Business),” February 24, 1910; “Kimssiuiyeon (김씨의연; Mr. Kim’s Donation),” March 4, 1910; and “Dojeognom Hangaji (도적놈 한가지; Same to Burglar),” March 17, 1910.

“Teukbyeolsajingwanggo (특별사진광고; Special Advertisement of Photography),” Hwangseong Sinmun, December 19, 1903.

“Sajin'gwaneul hwakjang (사진관을 확장; Expansion of Photo Studio),” Deahan Maeil Sinbo, September 15, 1907.

“Sajin'gwanheungwang (사진관흥왕; Photo Studio Is Thriving),” Deahan Maeil Sinbo, March 4, 1908.

“Buinsajin'gwan, Buinsajinsaroneun Yi Hong-gyeongssiga Cheoeum (婦人寫眞館, 부인사진사로는 이홍경씨가 처음; Yi Hong-gyeong Is the First Woman Photographer Opening a Photo Studio for Women),” The Choson Ilbo, May 22, 1921.

“Yangsajin'gwan Daesusaek, Gyeongseong Sajin'gwanwon Jeonbu Inchi, Dongyang Sajin'gwaneseodo 1myeong (兩사진관 대수색, 경성사진관원 전부 인치, 동양사진관에서도 1명: Two Photo Studios Searched, All Employees Arrested from Gyeongseong Photo Studio, One from Dongyang Photo Studio),” The Choson Ilbo, November 15, 1928.

“Sajingi Dojeok, Bonjeongseoe Japieo (사진기 도적, 본정서에 잡히어; Camera Thief, Caught by Police),” Jungoe Ilbo, August 29, 1928.

“Sajingi Dojeok (寫眞機盜賊; Camera Thief),” The Dong-A Ilbo, June 8, 1934.

“Yurichangpason, Sajin'gwan Jibung(jibung)i Deoug Simhae (琉璃窓破損, 사진관 집웅(지붕)이 더욱 심해; Damage of Windows, Roofs of Photo Studio Worse),” The Dong-A Ilbo, September 25 1924.

“Gyeongseonge Seumnaehan Daebang Cheukusogaeseolhusingirog Sajin'gwannyuricheonjeongeun Jeonmyeol (京城에 襲來한 大雹 測候所開設後新記錄 寫眞館琉璃天井은 全滅; The Big Hail in Gyeonseong, New Record Since the Establishment of Weather Bureau, Glass Roofs of Photo Studios Shattered),” The Dong-A Ilbo, October 2, 1932. Taishō designates the years in which Taishō was the Japanese monarch from 1912 to 1926. Thus, 6th year of Taishō is 1917. (translator’s note)

“Sajin'gwanhwajae, Wonineun Nudyeonin deut Sonhae Chilcheonwon (寫眞館火災, 원인은 누뎐인 듯 손해 칠천원; Photo Studio on Fire, Seemingly From a Short Circuit, Damage at 7,000 Won),” The Dong-A Ilbo, May 31, 1929.

“Jinjue Daehwa, Ilbonin Sajin'gwaneseo (진주에 대화, 일본인 사진관에서; A Big Fire in Jinju, in a Japanese Photo Studio),” Jungoe Ilbo, May 17, 1927; “9il Saebyeong 1sie Samseong Sajin'gwan Jeonso (9일 새벽 1시에 삼성 사진관 전소; Samseong Sajin'gwan Burned Down around 1 a.m. on the 9th),” The Choson Ilbo, December 11, 1932; “Hwaroeseo Balhwa Sajin'gwani Jeonso (화로에서 발화 사진관이 전소; A Photo Studio Burned Down by Fire from a Brazier),” The Choson Ilbo, January 18, 1934.

“Joseonsajinhyeopoe Changnipchonghoe (朝鮮寫眞協會 창립총회; Inaugural General Meeting of the Joseon Photography Association),” Maeil Sinbo, June 24, 1942.