The Challenging Archive: Studying Photographers of the Chinese Communist Party

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

For the past decade, our research has focused on a group of CCP (Chinese Communist Party) photographers whose careers span from the 1930s to the 1980s. Despite their prominence in Mao’s China, neither their careers nor their works have enjoyed in-depth studies that go beyond generalized analysis of “propaganda.” As most of them began their work during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), their photography played an important role in mass mobilization, either documenting the war or recording various campaigns in the Communist bases known as the Liberated Areas.

Thanks to training classes launched by the party, the number of the CCP photographers grew steadily and reached a few hundred by 1946, when the domestic war between the Communist Party and the Nationalist Party resumed. After the Communist Party took control of mainland China and established the People’s Republic of China (PRC), in 1949, this cohort formed the nucleus of the top photography circle of Mao’s China. Their proven loyalty to the party landed them in prestigious positions.

Like the other early PRC political and cultural elite, these photographers suffered persecution during the tumultuous years of anti-rightists campaigns and the Cultural Revolution. Those who survived continued to work after the Cultural Revolution, until their retirement in the 1980s. Through lectures, exhibitions, and publications, their visions and voices continued to influence Chinese visual cultural for the next decades.

The work and lives of the CCP photographers are indispensible to our understanding of the history of twentieth-century Chinese photography. Nevertheless, the condition of collections of their works remains a great challenge. In general, their images are difficult to access, and many have yet to be declassified. The biggest challenge, however, lies in attribution. A large number of their photographs were not signed or were signed under collective authorship, and attributions of photographs taken during the war years of the 1930s and 1940s bear many mistakes. Some are a natural result of the chaos surrounding the production of war photography; others reflect the turbulent history of archives themselves—for example, the merging of those of the three main CCP pictorial magazines: Jinchaji Pictorial, Huabei Pictorial, and The People’s Liberation Army Pictorial. In addition to misattributions caused by circumstance, some photographs were deliberately mislabeled. For instance, photographs of one battle would sometimes be recaptioned to represent a more significant battle that did not have its own photographic records.

Although attribution is not an uncommon challenge, especially in fields such as vernacular photography and survey photography, the archive of CCP photographers requires special scrutiny.

We have approached the photographs—previously treated as mere illustrations of historical texts—as the primary subject of inquiry. Borrowing methods from art history, we have compiled a body of works of individual photographers that can then be used as a frame of reference for further study. Our attributions are based on two efforts.

First, we unearthed the records and negatives from the photo archives of the major CCP pictorials, which often bear the names of photographers, names that were erased or obscured by collective authorship in the subsequent use of the images. As the negatives were developed during hectic military marches, each photographer came up with ingenious methods of making impromptu “darkrooms,” which produced valuable images but imperfect negatives. The marks of deficits turned out to be characteristics that greatly helped our identification.

Second, in the past few years we interviewed more than two hundred people, among them CCP photographers, their colleagues, their relatives, and their friends. The photographers themselves were the most reliable identifiers of their own works.

The rich oral history we have compiled through this project is crucial to the understanding of these photographers’ experience and self-identity.

It is worth noting that our project has heightened our own awareness of the underlying criteria by which photographs were highlighted in previous publications. For example, those editors of newspapers and magazines who wanted to show historical significance and those featuring artistic achievement would select different photographs. When we returned to the negatives and archive record, however, we often encountered photographs that were excluded by those criteria. Considered to be “not that important,” such photographs reveal a great deal about the career and style of individual photographers. In wartime, for example, photographs were chosen based on the particular significance of the war they documented. On the other hand, a series of photographs of a now forgotten battle might bring to light the unique compositional and narrative style of the photographer.

Based on our research, we managed to match to their photographers thousands of images taken during times of war and millions taken after 1949. We developed an archive that is anchored in individual photographers, each with a considerable body of photographs supplemented with textual materials such as their writing, speeches, correspondence, and even confessions and self-criticisms from the anti-rightists campaign and the Cultural Revolution.

Although we began with inspiration from art history, further studies led us to domains such as social history, cultural history, and media studies. Not only have these materials enabled us to conduct in-depth studies that enrich the writings of histories of Mao’s China and challenge the simplified understanding of “propaganda,” but we have also started the process of publishing these materials, despite several obstacles, among them censorship of sensitive materials and a lack of funding.

Our project of building an archive of CCP photographers is ongoing and our research based on this archive is still preliminary, but we would like to introduce a few observations with the examples of photographs of the Liberated Area in northern China taken between 1947 and 1948 by two CCP photographers, Gao Liang (1921–2006) and Wu Qun (1923–1996).

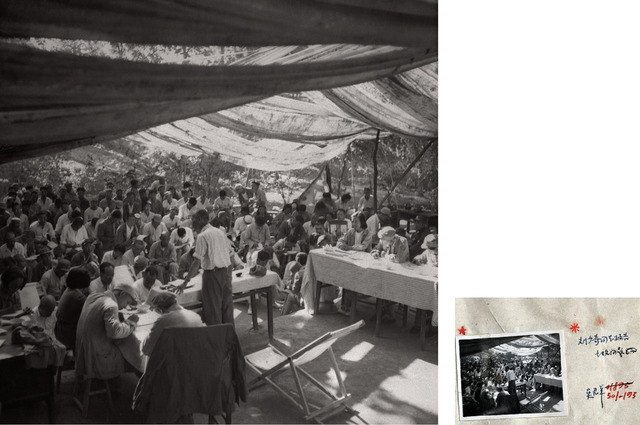

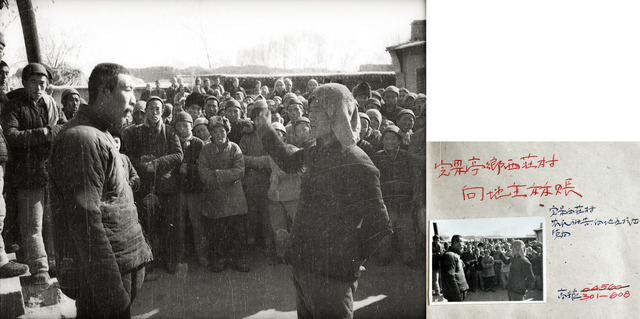

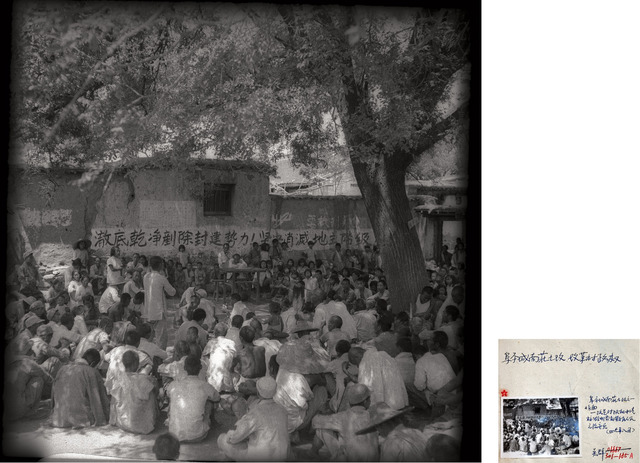

Figs.1.1 and 1.2. Gao Liang, “Peasants had it all out with the landlord, Xi Zhuang village, Wan County.” On the right (fig. 1.2) is an archive record with a handwritten caption.

Figs.1.1 and 1.2. Gao Liang, “Peasants had it all out with the landlord, Xi Zhuang village, Wan County.” On the right (fig. 1.2) is an archive record with a handwritten caption. The handwriting of captions on archive records helps us identify the archivists and provide important clues to be able to date when these photographs entered the archives. The records also contain numbers for the negatives, and these help us reconstruct the original sequence in which the photographs were taken. The negatives next to each other are very likely taken by the same photographer, which we can confirm by the condition of the originals.

The captions on archive records were based on information jotted down by the photographers, but were often altered in subsequent disseminations of the pictures. An original caption that contains the date, location, and content of a photograph was gradually transformed into a vague caption loaded with ideological messages. This phenomenon has contributed to later misidentification, which made these original captions invaluable evidence for our identification and reattribution.

Our research shows that about twenty percent of the photographs were misattributed or misidentified. We strove to correct these mistakes by meticulous comparison between archive records and other resources, as well as detail-oriented interviews with photographers.

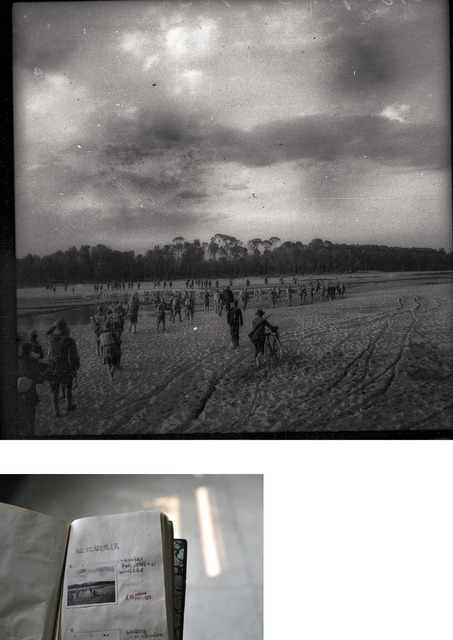

Figs. 2.1 and 2.2. Wu Qun, “PLA were marching across the Yang River, advancing on Yuguan,” May 1947.

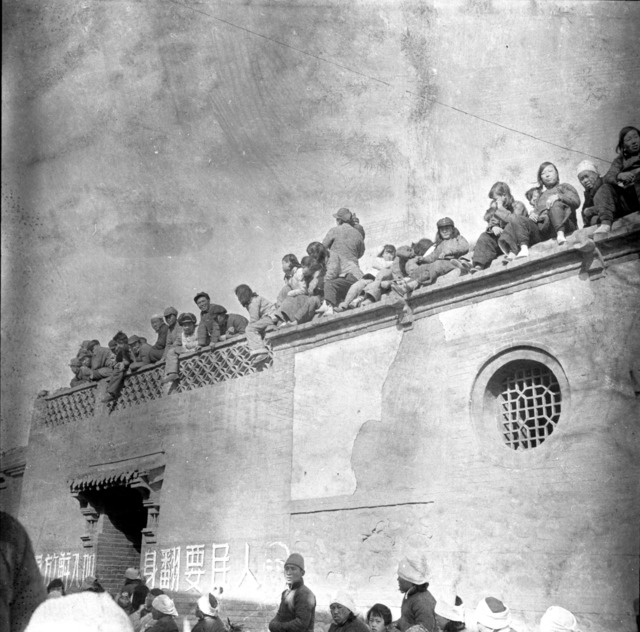

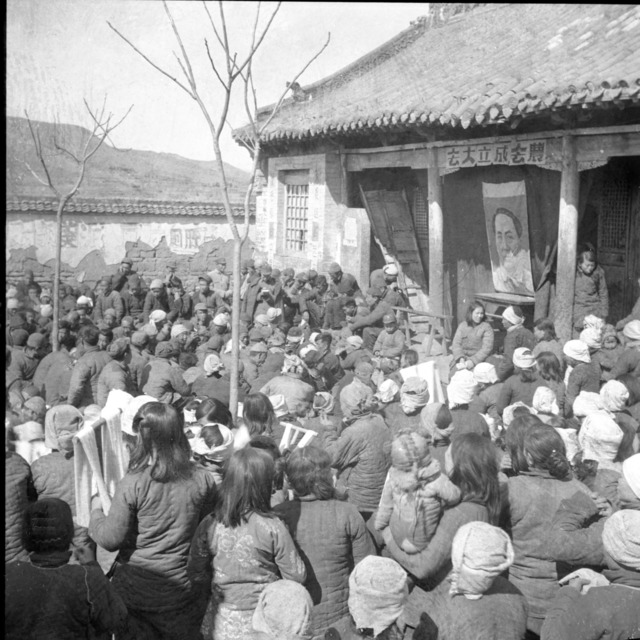

Figs. 2.1 and 2.2. Wu Qun, “PLA were marching across the Yang River, advancing on Yuguan,” May 1947. Figs. 2.3 and 2.4. Wu Qun, “One scene of Land Reform in Fuping: Exposing and criticizing the sheriffs who had bullied and oppressed the people.”

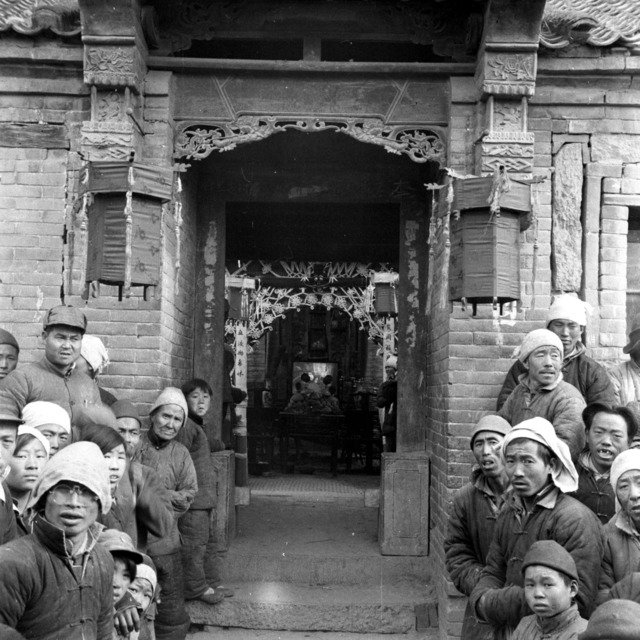

Figs. 2.3 and 2.4. Wu Qun, “One scene of Land Reform in Fuping: Exposing and criticizing the sheriffs who had bullied and oppressed the people.”The majority of CCP photography in the late 1940s focused on the war. The small amount that reflected economic, political, and social aspects of life usually centered on specific themes, such as land reform. These images, despite their small number in relation to those relating to the war, are significant, as they established the visual paradigm for the vast amount of propaganda photographs after 1949. The photographs of land reform demonstrate striking similarities, both in subject matter and in modes of expression. Two themes stand out: peasants beaming with delight and landlords dispirited by their doomed future. Whereas the first theme confirms the legitimacy of the redistribution of land and visualizes the concept of “the people,” the second echoes the converging discourses of class antagonism and patriotism that justified the confiscation of land from landowners, with the dual accusation of exploitation and treachery.

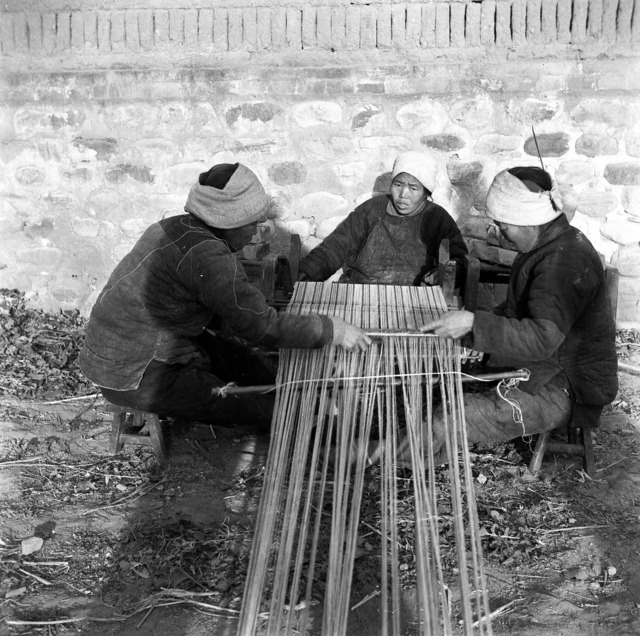

This approach of the CCP photographers becomes even more evident when their works are compared to those taken during the same period by two members of the British Communist Party: David Crook and Isabel Crook. In late 1947, David and Isabel Crook arrived at the village known as the Ten Mile Inn (Shilidian), in the Jinjiluyu Liberated Area. Trained in sociology and anthropology, the couple came with the purpose of observing, recording, and even participating in China’s revolution. Their eight-month stay led to some seven hundred photographs and two publications about the village.

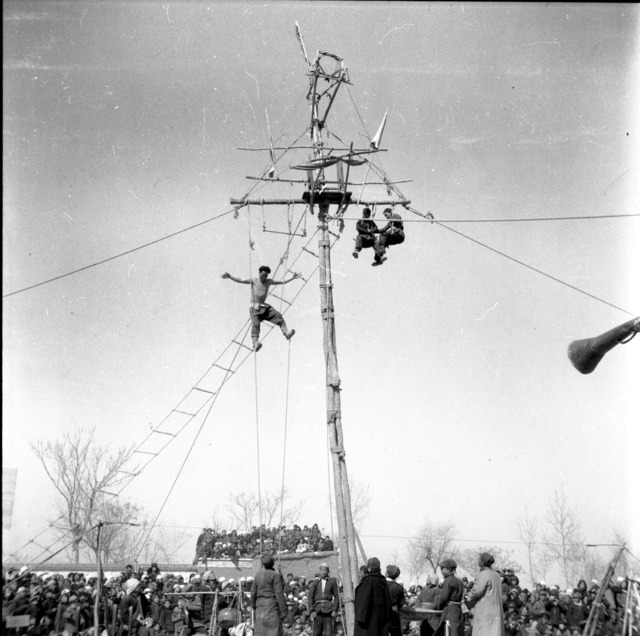

Although their photographs were used only sporadically in their publications, over a period of twenty-two months we repaired and meticulously cataloged the entire lot. These photographs not only record a series of historical events including land reform and CCP rectification, but also capture the village’s everyday life, including ceremonial activities such as festivals, rituals of ancestor worship, weddings, and funerals, thus revealing the traditional economic structure and cultural system in rural northern China through skilled anthropological observation.

The goal of the photographs by the Crooks was to capture various aspects of rural life—an approach reflecting their identities as scholarly Western Communists and continuing the documentary tradition of photography as social survey. The CCP photographers, on the other hand, aspired to interpret and validate the reality of the Liberated Areas. The approach of the CCP photographers should be understood within the context of the collective imagination of the Chinese Communist revolution. Their production of images, just like literary production of the same period, helped to generate and consolidate a new understanding of justice, class, and the “people.”

The way by which the photographers interacted with their subjects, along with the mechanics of photographic production, continued after 1949. Their wartime photography, however, which could rarely be posed or staged, was transformed into reports of daily life loaded with ideological messages. The idiosyncratic methods individual photographers developed during the war also became deliberate pursuits of a personal style. Bravery, the once highly valued quality of war photographers, was replaced by political sensibilities as the new criteria for evaluation and promotion in the genre.

We also want to highlight the distinctive condition of the archives of CCP photographers and the challenges it posed to scholarship. The study of the work of Wu Qun and Gao Liang could not be advanced without the development of a much larger project that investigates the CCP photographers as a group. In other words, if we approach the archives with the intention of doing case studies of individual photographers, we would not be able to define a reliable set of core materials that would lead to meaningful discussion. The current stage of the study of CCP photographers requires researchers to clarify the general conditions of their production and conduct basic attribution and identification of photographs before they can advance.

GAO Chu is a graduate student in the Communication University of China (CUC). His research focuses on Chinese photographic history, primarily from the 1930s to the 1980s. He has spent more than ten years interviewing senior photographers of this period, and helped them to edit their negatives, photos, and diaries and to finish a series of case studies. He is also an editor and curator. He is now conducting fieldwork in the Ten Mile Inn for a book that will use texts, oral history, and photographic materials to describe the vicissitudes of a village. WANG Shuo, an independent scholar of Chinese classical literature, is also interested in Chinese photography. She has participated in the project of collecting, sorting, and exploring the photos taken in rural northern China; is a core member of David and Isabel Crook’s photography project; and serves as co‐curator of the exhibition “North Rural China: 1947–1948.”