Claire Roberts, Photography and China (London: Reaktion Books; Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013) 200 pp. ISBN978-988-8139-88-0 (Hong Kong ed.)

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Claire Roberts’ new book, Photography and China, addresses a contemporary need that has often been invoked but not well satisfied, until now. The power and vitality of photography in China have never been greater, nor have Chinese photographs ever been in circulation more widely. Yet we have to hand: a) no general English language survey; b) no broad overview of practices of Chinese photographers in the context of Chinese social and cultural history along with international currents; c) no extended critical narrative that examines numerous specific photographs in relation to these contexts; and d) no single book that is succinct but comprehensive and easy to include in non-specialist syllabi for the global study of “the history of photography.” Based on Roberts’ extensive knowledge of China, her active and highly respected curatorial career, and her voluminous research in scholarship and archives within and outside of China, Photography and China makes a very convincing bid to be that book.

In a series of linked chapters and brilliantly juxtaposed photographs, Photography and China tells its story by examining Chinese photographs from Chinese photographers’ points of view. Roberts shows the myriad ways in which these photographers have long been in dialogue with Chinese society as well as with foreign trends. The narrative begins with adaptations to the earliest introduction of photography into China, and ranges, roughly speaking, through the turbulence of foreign associations and self assertion in the late-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, the Communist and the Cultural revolutions, the period of “Reform and Opening,” and ends with a very insightful account of the contemporary scene. Throughout, Roberts also strives to give the reader some sense of the uses Chinese photographers were making of traditional forms of visual and spiritual representation, such as brush and ink painting, as well as the mechanical image. “I explore photography,” Roberts writes, “as an entrepreneurial, revolutionary and innovative medium, and as a means of ‘transmitting spirit’ (chuan shen).” (9). It is particularly impressive how this line of spirit weaves throughout the highly varied situations within which Chinese photographers have worked, to yield something of a sense of the continuity of the will to witness, amidst the breaks and turns of the past nearly two centuries of Chinese history. This witnessing may be functionary, instrumental, documentary, psychological, contemplative, performative, or otherwise. But one puts down the book with a sense of having followed an impulse to record with the camera that has been in a complex dialogue with Chinese facts and Chinese people in many forms. It’s an exciting, enabling and distinctive premise with which to examine this subject.

Roberts’ basic argument is that photography plays a major part in both making and reflecting “the tensions between past and present in a society undergoing dramatic political and technological change.” (63). Chapter by chapter, the book traces these points of dialogue and elaboration between society and the camera in China. In a sense, Roberts is the Robert Taft, or the Giselle Freund, of Chinese photography, imbedding the art in its social history. Chapter One, “China Exposed,” begins with foreign implantation and ends with Chinese hybridity. Chapter Two, “The True Record,” gives an invaluable account of the many photographic studios and published albums that swiftly arose in the wake of the opening of the treaty ports and cities and that served the needs of expatriate businessmen as well as the Chinese merchant class. Chapter Three, “China Modern,” explores the erudition of Shanghai and other cities in the Republican period, following the growth of studios, print publications, movements and clubs. Chapter Four, “War and Propaganda,” is consumed by war and revolution, as China itself had been, and Chapter Five, “Reportage and the New Wave,” movingly describes the ways that “people’s photography” slowly freed itself from the strictures of military propaganda. This upwelling, Roberts explains, was accomplished by “individuals - many of them from families of political or cultural influence – who had experienced the trauma of the Cultural Revolution and, no longer content merely to witness history, wanted to record their own perspectives and life experience.” (121). Chapter Six, “U-Turn,” demonstrates the artistic flowering of that irresistible current into an artistic avant-garde that opened China once again to direct conversation with artists from the West while freeing domestic introspection.

This is not at all a simple line of progress, however. Robert shows how photographers expressed growing awareness of the burdens of the past as well as the confusions and dislocations of a future frighteningly put at risk once again in the events and aftermath of June 4, 1989. And Chapter Seven, “Performing into the Present,” searchingly analyzes Chinese photographers’ new artistic prominence and meditative self-assurance for continuities as well as breaks, as they picture the rapidly changing conditions of self and society in China for hungry viewers both at home and abroad.

Roberts’ prose must be praised for its economy as it unfolds this nearly two century long story; and it must be praised as well for its generosity, because it is only due to her economy that so much can be said. On a first reading, perhaps one might be simply excited by the panorama, but on a second and third thereafter, one comes to understand how very much is being seen and told. In large part, Roberts’ perspective is best supported not by her clear and careful prose argument, however, but by her exposition of how the beautifully reproduced photographs in the book both express and influence social change. She seeks to demonstrate “a process of cultural encounter and transfer, like painting in its absorption of introduced materials and techniques, [through which] photography became a Chinese medium, used for a wide variety of public and private purposes.” (8). And she shows these relationships best when showing them literally, in the interlacing of images. In this, she excels.

Fig.1: Jules Itier, Qiying and members of the French embassy on board L’Archimede, 24 October 1844, daguerreotype.

Fig.1: Jules Itier, Qiying and members of the French embassy on board L’Archimede, 24 October 1844, daguerreotype. For example, when Chapter One explores the earliest decades of photography in China, it begins in an externally-imposed foreign cultural encounter and weaves it back into Chinese domestic life. At the start of the process, Roberts proposes, is a calotype copy made in London of the signed Treaty of Nanking (1842). This treaty ended the First Opium War in a series of humiliations for China that included foreign rights to treaty ports in Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai, the loss of Hong Kong to Britain, and punitive financial payments in retribution for the war. On a downward spiral for Chinese autonomy that clarifies the pun in the chapter title (“China Exposed”), the next photograph to be discussed in the first chapter, and the first to be reproduced, is a sort of echo of the first: an 1844 daguerreotype by Jules Itier of “Qiying and members of the French embassy on board L’Archimede.” (Fig.1) The dignitaries are barely visible but the occasion is clear; the daguerreotype commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Whampoa, in which the French extracted rights similar to those of Britain two years earlier. Given that the first signing went unrecorded, the second stands in for such occasions. Yet Roberts does not rest her analysis on the obvious observation of the imperial nature of both of these events, with their asymmetric powers. Rather, she builds a web of outcomes that far surpasses a binary framework.

Thus, the chapter goes on to observe the “solemnity” and “decorum” by means of which the compromised Chinese still assert strong presence in the shadowy Whampoa image; the poetic suggestiveness of its oval frame, the circulation of Itier’s daguerreotypes as gifts in diplomatic rituals; the (re)-admission of French Jesuits to China as part of the treaty of Whampoa; the effect of this foreign presence on early daguerreotype portraits of Jesuit and Chinese scholars alike; the eventual death of one of these pictured missionaries in an anti-foreign riot in Shanghai; the rise of the foreign language press; the subsequent desire and even necessity for Chinese elites to present a distinguished face to both the domestic and the foreign public, at home and abroad; and the rapid growth of a thriving transnational commercial photography studio sector including in Hong Kong, where a terrific image from 1867-8 shows the English-named studio of William Pyor Floyd with Chinese staff leaning from its second story balcony; and on through an extended discussion of the development of commercial photographic portraiture in China. The chapter ends with an elegant early twentieth century image of a father and son from the ‘Tai Kang True Face Photographic Studio’ in which their “true face” seems indeed to be expressed in a double portrait that comprises both expert technological realism and “an idealized, illusionistic space” that is “adapted to a Chinese conceptual setting.” (39). All of this denouement and more is linked backward and forward in time and is traceable, although not reducible, to that very first “smeary, pitted and scratched” (12) shipboard image. For Roberts, the story of encounter in Chinese photography is never static or unidirectional, but represents the expansion of ideas, the communication of change, the call and response or provocation and reply that radiate from particular historical points, such as the two treaties, and transform both the people of China and those who would rule. It is arguable that this is also the character of modernity itself, which literally arrived in China along with the camera.

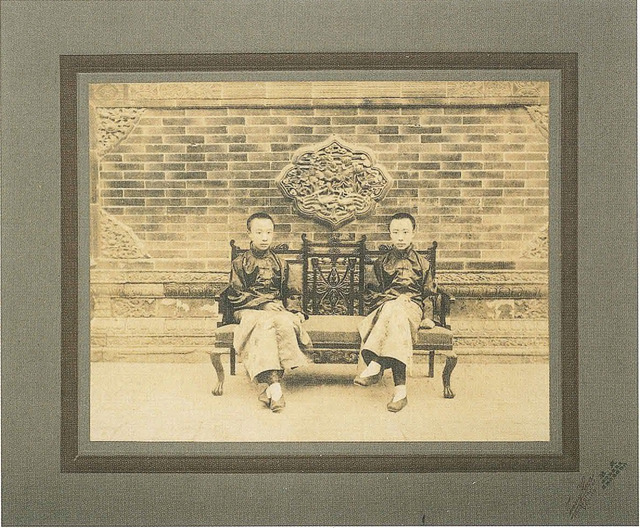

It is impossible to do justice here to the pleasure of chapters that present such wonderful opportunities for contemplation by means of such a great richness of illustration. Despite its scholarly and carefully crafted textual argument, the book is really driven by its illustrations. Many stunning Chinese photographs are reproduced here for the very first time, and there are many continuing conversations to uncover by observing the sets of images themselves and thinking them backwards and forwards. For example, the technically brilliant trompe l’oeil creation of contemporary digital artists is clearly genealogically connected back to the genre of double exposed “images of me and myself” (erwo tu), technical tours de force from the early 1900s. A particularly beautiful example of a double portrait of Aisin-Gioro Puyi is included in Chapter Three, “China Modern.” (Fig. 2) It was apparently made to help amuse the young Puyi, who had lost his throne shortly before. This same boy, when grown, would become the Emperor of Manchuko (1934-45) under its occupation by Japan. His is a life story that is well expressed from start to close by doubleness, an irony that fascinated Chinese people in the past and is pungently alive in the expressions of today’s Chinese artists as well.

Fig.2: Double-exposure portrait of Puyi, early 1900s, gelatin silver print on card, photographer unknown.

Fig.2: Double-exposure portrait of Puyi, early 1900s, gelatin silver print on card, photographer unknown. Another particularly powerful example of dialogue ends the book. In a sense, Roberts’ story ends where it begins, although of course with a difference. The final words in the book pair a prize-winning staged self-portrait by Chen Wei (b. 1980), “Lighthouse Was Winking in the Far Distance” (2000), with the 1842 daguerreotype of the signing of the Treaty of Whampoa, discussed at length at the start. In that shadowy early picture, the faces of the imperial officials are indistinctly lit and they cannot be discerned. They sit stoically to be recorded by a new machine that is operated by their enemies, and Roberts observes that they ”gazed into the mysterious scrutiny of an uninvited record.” (183). In 2000, Chen Wei also staged a portrait of himself sitting in a dignified pose in front of a painted backdrop, referencing those early studio photographers in Hong Kong. His face, too, is indiscernible – but this time because the light is too intense. Chen tells us that the obscuring light in his portrait comes from a “lighthouse winking in the far distance,” although no such lighthouse is visible in the image itself. The Treaty portrait is a record of a shipwreck. But just perhaps there is the hint of promise that new shoals might be avoided, as the Chinese sitter now controls the power of the gaze. Roberts’ repetition marks the great passage of time and shifts in technology and events that underlie Chinese approaches to photography today. “The difference is,” Roberts concludes, “that the people behind the camera today are young Chinese photographers – professionals and amateurs, photojournalists, photographers of the people, and artists – conjuring images from darkness and light in an attempt to make sense of their worlds.” (183).

Laura Wexler is Professor of American Studies, Professor of Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies at Yale University, and Director of The Photographic Memory Workshop at Yale. She is author of Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of US Imperialism, and is co-author, with Sandra Matthews, of Pregnant Pictures. She has also published numerous articles on the history and criticism of photography. Her recent essay on cultural memory and Chinese family photography, ”’The bridge connecting them to ourselves:’ Childhood, Photography and Memory in Contemporary China,” appeared in the Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, Volume 4, Issue 1, Fall, 2011.