Traces of Life: Seen Through Korean Eyes, 1945-1992 (New York: The Korea Society, 2012) 136 pp. Chang Jae Lee, ed., with contributions by David R. McCann and Sun Il. ISBN 9788974092894. In English and Korean.

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Koo Wangsam’s A Flock of Children (1945) provocatively confronts the viewer with contradictions of modern Korean history’s past, present, and future. It shows the barrenness of a scorched tree set in the foreground of a vast horizon with the youthful energy of children as they climb on it, perch on it, cling to it, and look up to it. Most likely a scene taken during the summer of 1945, immediately before Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonialism, this photograph uncannily evokes how Walter Benjamin describes Paul Klee’s Angelus Novous:

This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceived a chain of events, he sees a single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.... The storm irresistibly propels him into the future which his back is turned (257-258).[1]

Likened to Benjamin’s angel of history, the subject of Koo’s photograph of a flock of children is suspended somewhere between past and future, which historians of Korea have poignantly named haebang konggan (해방공간). This time and space designation can be literally translated as “a space of liberation” but it refers more precisely to the time and space of post-liberation Korea before the establishment of the two Koreas in late 1948 or extending it bit further to the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950. However, unlike Angelus Novous, who directly sees the horrifying wreckage gathering in front of him, in Koo’s photo the children play as though oblivious to the impending liberation from 35 years of Japanese colonial rule and the future’s storms that are rushing toward them in the form of national division, the Korean War, military dictatorships in both Koreas, the excruciating cost of rapid modernization, industrialization, and democratization in South Korea. Perhaps that is what makes this image so much more stirring. The undesignated and unidentifiable place will soon undergo national division to become either the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North) or the Republic of Korea (South). The unidentified young boys enjoy their brief respite despite the graying, cloudy skies and the winds that blow under them, hardly aware that they will soon be forced to scatter either north or south.

Fig. 1: Koo Wangsam, A Flock of Children, 1945, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Koo Wangsam, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York.

Fig. 1: Koo Wangsam, A Flock of Children, 1945, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Koo Wangsam, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York. Thus opens Traces of Life, the catalog edited by Chang Jae Lee in conjunction with the exhibition of post-liberation Korean photography curated by Chang Jae Lee and coordinated and managed by Jinyoung Jin of the Korea Society of New York, which was on display from September 19 to December 7, 2012 at the Korea Society Gallery.[2] It is a powerful opening and undoubtedly sets an equally impressive tone for the entire volume, which features fifty-four black and white photographs of thirteen pioneering Korean photographers whose work spans the years between 1945 and the early 1990s. It includes the works of Koo Wangsam, Kim Kichan, Kim Soonam, Kim Hanyong, Yook Myungshim, Lee Hyungrok, Lee Haesun, Lim Eungsik, Chung Bumtae, Joo Myungduk, Choi Minsik, Han Youngsoo, and Hong Suntae. Traces of Life is currently on display at the Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, and also at the Jorgensen Gallery at the University of Connecticut. All works are on loan from the Dong Gang Museum of Photography in South Korea[3] and the estates of Kim Kichan and Lee Hyungrok.

In recent years, with the growing interest in fin de siècle Korean visual culture and history, several exhibitions and exhibition catalogs (both in Korea and abroad) have brought attention to photography as a crucial source of understanding and visualizing Korea’s past.[4] All of these exhibitions and publications are invaluable sources that provide us with a fuller documentation of life and landscape of the late-19th century and early-20th century Korea. Interestingly, however, many if not all of the photographs in these volumes are images taken of Korea and Koreans by non-Koreans, whether they are missionaries, government officials, travelers, etc., from the West or Japan. Indeed, an examination of the history of early photography in Korea reveals that the representations of Korea were intertwined within the broader systems of global imperialism and Japanese colonialism. Hence, the question of what constitutes Korean photography and what might representations and recordings by Koreans look like have been raised. To be sure, there is a history of Korean photography before the post-liberation period. Some important Korean figures in the history of early photography are: Chi Unyŏng (1852-1935) who in 1884 is said to have photographed the then Korean, monarch, King Kojong; Kim Kyujin (1868-1933), who is said to have studied photography in Japan after which he founded the Ch’ŏnyŏndang Photo Studio in 1907; and Min Ch’ungsik (1890-?) who learned the techniques and the art of photography from classes offered at the Seoul YMCA and then went on to play an instrumental role in teaching photography. Moreover, the founding of vernacular Korean newspapers such as the Maeil sinbo (매일신보) (Maeil News, 1910), Choson ilbo (조선일보) (Choson Daily News, 1919) and Tonga ilbo (동아일보) (Tonga Daily News, 1920) contributed greatly to not only making photographs an everyday sighting for the readers but also introducing new genres, such as photo journalism, and promoting amateur photography through a number of contests that the newspapers sponsored. Unfortunately, as Sun Il points out in the essay he contributed to Traces of Life, there is a dearth of data on early Korean photography from the late 19th century and early 20th century (3). Thus, the importance of the photographers and their works in Traces of Life cannot be overstated.

Traces of Life features works by Korean photographers, most of whom were born during the Japanese colonial period or soon after the August 15, 1945, liberation, and lived through the three years of civil war, military dictatorships, industrialization, modernization, and eventually the democratization of South Korea. This group of Korean photographers makes up the generation that moved away from art photography (yesul sajin/ 예술사진) to advocating realism and documentary photography, thus becoming founders and leaders in the realist movement. Of the thirteen whose works are included in this catalog, only five are still living.[5]

The works collected in the Korea Society exhibition and catalog poignantly bring out the everyday life of Koreans during the mid-century when they were living in the midst of modernization. Unlike the first time visitor to 21st century-Seoul who would encounter one of the most densely populated cities in the world, filled with skyscrapers, congested highways, and endless store fronts, the scenes documented in these photographs indicate Korea had yet entered the threshold of modernization. However, while the majority of the landscape is still agricultural (Lee Hyungrok, Morning in the Mountain Village, 1975), and the cityscape bares unpaved, muddy streets (Lee Hyungrok, Muddy Street, 1954), many photographs selected for Traces of Life project obvious signs of looming modernization and consequences of that process in the making of an urban city, especially Seoul.

Fig. 2: Kim Kichan, Gongdŭk-dong 1992, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Kim Kichan, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York.

Fig. 2: Kim Kichan, Gongdŭk-dong 1992, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Kim Kichan, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York. The catalog presents Kim Kichan’s alley series in a wonderfully recollective order that allows us to look up, look deep, and look across to see life inside of Seoul.

Kim, who is best known for his work documenting alleys in Seoul, captures an intimate look “inside” of Seoul, taking the viewer through narrow, maze-like alley ways where life happens—kids play, people work and sleep, the sun sets and rises. As the caption mentions, the row houses lining these narrow alleys were part of Park Chung Hee’s rapid industrialization policy that transformed dirt paths into cement streets only to be bulldozed and demolished later in order to clear space for modern highrise apartments. The omnipresence of alleys, clearly visible as part of the Seoul landscape even as late as 1992, has now been largely eclipsed by highrise apartment buildings displacing people from their homes and completely altering neighborhoods, even as far as expunging them from existence. Hence Kim Kichan’s alley photos, especially Gongdŭk-dong 1992, which is the most recent photograph in the catalog, seemingly alludes to the future of alleys—-empty, silent with only faint wall writings remaining like an abandoned cave.

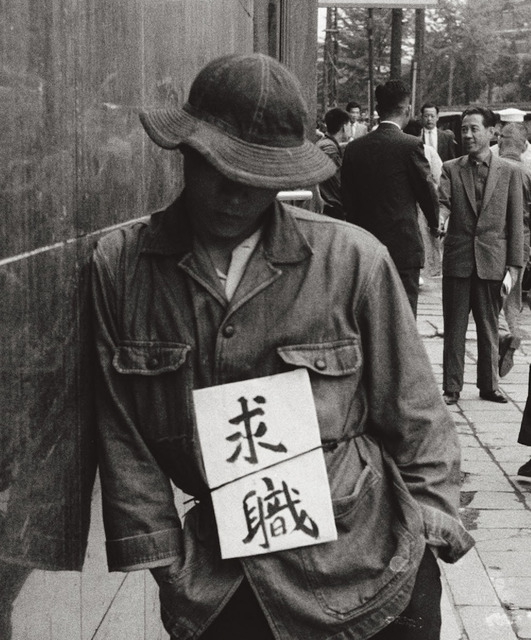

Fig. 3: Lim Eungsik, Looking for Work, 1953, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Lim Eungsik, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York.

Fig. 3: Lim Eungsik, Looking for Work, 1953, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Lim Eungsik, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York. Lim Eungsik’s Early Summer (1956) and Looking for Work (1953) perhaps best encapsulate the contradictory processes of modernization and urbanization. In both of Lim’s photographs contrasting symbols of modernity versus tradition and poverty versus wealth are deftly framed. For instance, in Looking for Work an unemployed man stands slouched in the foreground wearing a sign that reads “Looking for work” in Chinese characters while over his shoulder in the background we see neatly dressed men in western business suits exchanging handshakes as if they had just finalized an important business transaction. The photo, which was taken in Myŏngdong, an area of Seoul that serves as the city’s business and cultural center, exposes the growing class disparity among Koreans as the country undertakes modernization in the aftermath of the Korean War.

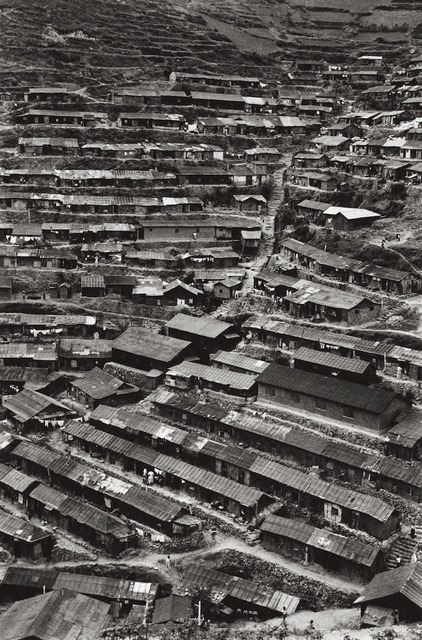

Fig. 4: Choi Minsik, Busan, 1957, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Choi Minsik, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York.

Fig. 4: Choi Minsik, Busan, 1957, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Choi Minsik, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York. The display of growing economic disparity and experiences of uneven modernity was not limited to the capital city of Seoul but was apparent throughout the country and in other urban centers. Choi Minsik’s photographs of Pusan, a port city in the southeastern part of the peninsula, aptly capture the growing pains and the effects of the War. Choi’s Busan, 1957, shows doleful living remnants of the (in)famous shanty town which was erected to accommodate the large refugee population during the war years.[6] Furthermore, similar to Lim’s Looking for Work, Choi’s Busan (1964) shows a nicely dressed mother in high heels and her young daughter leisurely looking into a shop window while a disheveled boy wearing rubber shoes passes by. He, unlike the little girl, is probably a child laborer working either as a shoeshine boy or doing some other menial work.

Fig. 5: Lee Hyungrok, Muddy Street, 1954, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Lee Hyungrok, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York.

Fig. 5: Lee Hyungrok, Muddy Street, 1954, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Lee Hyungrok, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York. Although the contemporary viewer might gasp at the images of the under-development and poverty of Korea in mid-century, these photographs pulsate with human life and unashamedly display the presentness of their lives. The photographers do not seem to be hurling an ideologically ridden critique or moral judgment through these images, but, rather, they frame their subjects with human agency. For example, the muddy streets, the horse-drawn wagon, and grimy buildings in Lee Hyungrok’s Muddy Street become really just an inconsequential background upon which we see a man crouching on the right side edge placing a stone in front of him so that the woman in the photograph could use it as a stepping stone to leap over the puddle. It is a simple interaction between two subjects that nevertheless shows the intimate connectedness (inyŏn 因緣) of human lives.

Moreover, even the photographs that appear to be delivering a social commentary cast the human subject and the landscape with sympathy rather than an ethnographic distance. For example, in Lim’s Looking for Work the gaze cast toward the unemployed man is so perfectly measured as if to protect the subject’s human dignity.

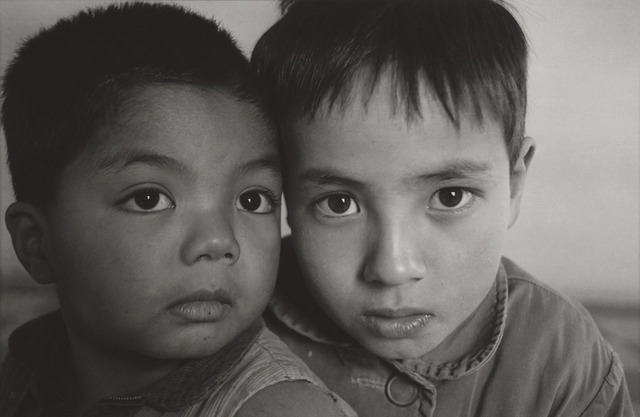

One of the most striking features of Traces of Life is the presence of children as prominent subjects. Joo Myungduk’s Harry Holt Memorial Orphanage series from 1965 is particularly arresting. These selected photographs, focusing on images of biracial children, document yet another aspect of the aftermath of the Korean War and the continuing U.S. military occupation. The children in Joo’s photographs look as though they are imploring the viewers with difficult questions pertaining to their racial, national, and cultural identities. That is, they look as though they are asking about their rightful place in the world despite being discriminated against for their mixed identities and being stigmatized as unwanted children. Thus, these images powerfully beseech the viewers not only with the traumas of the war and military occupation, but, more importantly, appeal to us to reconsider human acts of cruelty that judge other human beings based on their race.

Similar to Koo Wangsam’s A Flock of Children, which shows a group of children suspended in haebang gonggan (해방공간) the children in Joo Myungrok’s series on the Harry Holt Memorial Orphanage are also suspend neither here nor there or then and now. In this particular photograph, however, the young boy on the right looks directly into the camera while the boy on the left looks pass the camera. Unlike the boys in A Flock of Children who appear as though they don’t anticipate the future, the two boys in Joo’s photograph seem to be anxiously awaiting the future. They are calm but challenging, perhaps asking questions such as, “Who am I? Who do you say I am? Where do I belong? What kind of future awaits me? How can I shape my own future?” We might be asking, “Where are they now—still in South Korea? Or elsewhere? How can we trace their lives?”

Fig. 6: Joo Myungduk, Harry Holt Memorial Orphanage, 1965, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Joo Myungduk, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York.

Fig. 6: Joo Myungduk, Harry Holt Memorial Orphanage, 1965, Collection of Dong Gang Museum of Photography, © Joo Myungduk, Courtesy of Dong Gang Museum of Photography and The Korea Society, New York. Traces of Life marks a welcome addition to Korean visual studies, the history of Korean photography, and Korean history. Chang Jae Lee, a senior book designer at Columbia University Press and an independent curator, and Jinyoung Jin, Gallery Director of Korea Society, should also be acknowledged as pioneers for their admirable efforts to introduce the first generation of post-liberation Korean photographers and their works to larger audiences in the United States. It fills a large vacuum that has existed in the study of Korean photography and should serve as an important complement to the 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, exhibition on contemporary Korean photography.[7] In addition to the eloquent curatorial essays, Traces of Life includes a poetic prelude from David McCann as an introduction and a contributing essay from Sun Il, a curator at the Seoul National University Museum, who provides a succinct and informative history of post-liberation Korean photography. Traces of Life also provides much-needed, albeit brief, biographies of the photographers as well as a caption a list. The fifty-four photographs are organized by photographer, which lends an important peek at each photographer’s representative works, vision, and style, but we must realize that the number of photographs included in Traces of Life is quite small in relation to each photographer’s oeuvre. This glimpse should definitely peak interest in further exploring individual photographers in their own right for their compelling documentation of post-liberation South Korea. While many of the photographers featured in Traces of Life have had solo exhibitions and retrospectives and have published collections of their photography, bringing them together in one exhibit and catalog stunningly illustrates the multifacetedness of modern Korean photography and modern Korean history, in particular the crucial years 1945-1990 when South Korea was undergoing rapid transformation.

Jina E. Kim is Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies at Smith College, where she specializes in Korean cultural history. She is currently completing a book Intermedial Aesthetics: New Technology and New Media in Modern Korea.

Notes

Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Schoken Books: New York, 1968.

Throughout the review, I use the term “post-liberation” to mean post WWII and “postwar” to mean post-Korean War.

Dong Gang Museum of Photography (http://www.dgphotomuseum.com/), located in Yŏngwol, Kangwon Province, opened in 2005. It is the first public museum in South Korea devoted to photography. Since the opening, the Museum has held numerous solo and group exhibitions and retrospectives showcasing many of the photographers included in Traces of Life. The Museum also sponsors an annual Donggang Photo Festival.

Donald N. Clark, ed., Missionary Photography in Korea: Encountering the West through Christianity (Seoul: Seoul Selection, 2009) in conjunction with the Korea Society’s exhibition by the same name (May 19-August 14, 2009); Pak Hyŏnsun, et al., Sŏyangini mandŭn kŭndae chŏn’gi hanguk imiji (서양인이 만든 근대 전기 한국 이미지 ) volume 1-3 (Images of early modern Korea as seen by Westerners) (Seoul: Ch’ŏngnyŏnsa, 2009); John Rich, Korean War in Color (Seoul: Seoul Selection, 2010); Seoul City History Compilation Committee, ed., Seoul Through Pictures, Volumes 1-3 (Seoul: Mayor of Seoul, 2002).

In the past ten years, Busan’s Taeguk Village has become an object of revitalization where which the once drab wooden buildings have undergone drastic changes, so much so that it has become one of the most visited tourist sites in Busan, gaining the moniker “Korea’s Santorini.” Ironically, while the motley-colored block buildings and narrow maze-like alleys are attractive, many tourists also visit this hilltop village with a sense of nostalgia for the past. See South Korea’s official Culture and Tourism website: http://english.visitkorea.or.kr/enu/SI/SI_EN_3_6.jsp?cid=1056152.

Karen Sinsheimer, et al., eds., Chaotic Harmony: Korean Contemporary Photography (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2009)