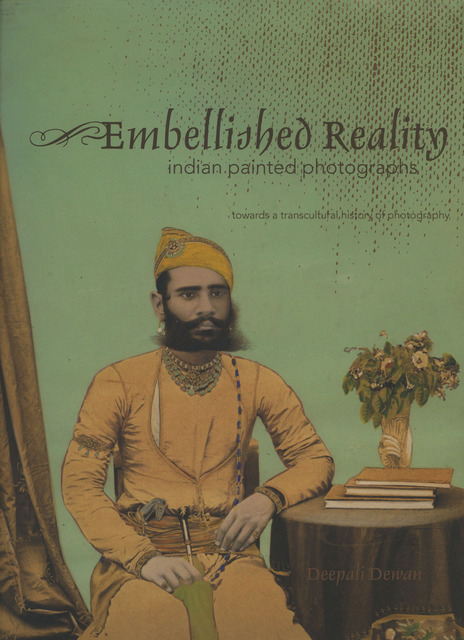

Deepali Dewan, Embellished Reality: Indian Painted Photographs: Towards a Transcultural History of Photography (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum Press, 2012) 119 p. ISBN 978-0-88854-481-0

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Tinting of photographs was a well-known Western tradition in the nineteenth century. With the colonial encounter, Indian artists combined their long-practiced art of miniature painting with the newly-developed technique of photography, creating a hybrid form of visual culture. Only a few years after the introduction of photography to India, most photography studios started offering their services to retouch the negatives or photographic prints and to tint photographs. Those studios hired skilled artists who were seeking work after losing patronage as a result of the decline of the princely courts, to add color to the black and white or sepia images.

As highlighted in this book’s sub-title, the author through this catalogue has tried to bring forth the fact that painted photographs right from their inception “instead of being product of a uniquely Indian visual practice”, can said to be markers of a ‘transcultural’ phase in the history of photography (p. 16). This aesthetic synthesis has been stressed with reference to the influx to India of London-published guidebooks relating to the painting of photographs and because of the growing awareness of the Indian miniature painters with the techniques of composition and overall colour management, as mentioned in those guidebooks. By the late nineteenth century, court painters from the Chitrakar family employed by the Rana rulers of Nepal were also sent to Europe to learn photography and the coloring of images.

Not much has been written on the genre of Indian painted photos, although the work of Judith Mara Gutman in Through Indian Eyes (1982), Christopher Pinney in Camera Indica: Social Life of Indian Photographs (1997), and the exhibition catalogue Painted Photographs: Coloured Portraiture in India (2008) by the Alkazi Foundation throw light on the theme. This exhibition catalogue adds substantially to the research done previously by including works from the contemporary period and also by documenting paintings that were executed in the tradition of photographic studio portraiture but have no evidence of a photosensitive material underneath.

This catalogue accompanies an exhibition of the same title, “Embellished Reality: Indian Painted Photographs,” held at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) from June 4, 2011 to June 17, 2012. The exhibition complements another exhibition held earlier at the ROM entitled “Bollywood Cinema Showcards: Indian Film Art from the 1950s to the 1980s.”

This catalogue of the “Embellished Reality” exhibition is comprised of two coherent essays, one dealing with the history and development of the painted photograph in India and the other with the study of the use of color in the manipulation of these images. The essays are accompanied by 70 full-page illustrations along with captions, most followed by brief descriptions of the works.

Trying to unravel how the Indian painted photographs were “part of a larger practice of photo manipulation and of the inter-ocular world of photo-based image production that can be said to be a marker of modernity [p. 33],” this catalogue covers works created by several known and unknown photographers and artists from all over the country. The foundation of this research is the study of painted photographs from India that have been acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum in the last decade, supplemented by works in other public and private collections. For the most part, the images cited are examples of studio portraiture, colored using mediums such as watercolor, oil paint, and gouache. This catalogue is a good read for the scholar as well as for anyone who wants to know about the subject.

The first essay is by Deepali Dewan, Senior Curator at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, who teaches at the University of Toronto. She has a keen interest in the history and the practice of photography in India, which has led her to explore this subject through her studies. One of her research areas is Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1904), a well-known photographer in nineteenth-century India. Dewan has co-authored a publication (forthcoming) on the same theme, entitled Raja Deen Dayal: Artist-Photographer in 19th Century India.

Through her essay “The Painted Photograph in India” Dewan distinctly puts across that the aim of this catalogue is “to sort through the different manifestations of paint and photography, their evolution over time, and the various networks of production and circulation [p. 16],” examples of painted photos covering diverse formats such as carte-de-visites, cabinet cards, postcards, lobby cards and showcards.

By an examination of the works and a review of primary documents and secondary literature, Dewan has compiled a brief history of the development of Indian painted photos in six broad overlapping phases from 1840 to the present day, examining the story of the evolution of this genre through pertinent examples from the ROM collection. The essay has been thoughtfully divided into sub-sections that are quite fluid and easy to comprehend, in terms of the language used.

Dewan’s research suggests that examples from the ROM’s collection can easily fit into the views propagated by both Western and Indian art historians that explore reasons for the use of color on monochromatic images. She cites examples in which paint was used both ‘as a tool to enhance the photograph’, especially in Europe and North America, and in multifarious roles in the Indian context. In India, a photograph was usually partially painted or completely painted over, leaving little trace of the original image. Nonetheless, the final product revealed the artist-photographer’s rich tradition of artistry and workmanship. As a creative technique, hand-painting offered unlimited scope in adding emphasis to an image. The artist used colour in an interpretative way to often change the background scene by adding or excluding certain decorative elements such as items of furniture, jewellery, and carpets or by changing the facial expression of the subject in order to show authority, grace, or kindness, as desired by the patron. The painted element became an integral part of the overall composition, thus giving the photograph a distinctive identity.

The inclusion of some tinted showcards and lobby cards, which are part of the vast arena of Bollywood, provides an intriguing reference point to the legacy of this art form even after India’s independence in 1947. Along with these, Dewan also examines work done in the contemporary period, where “the artists have appropriated the look and technique of the painted photographs as a way to explore a sense of the past and to push the boundaries between mediums in the present [p. 30].” This has been substantiated by examples of striking work done by contemporary artists like Pamela Singh and the New York-based artist Alexander Gorlizki. In the work titled ‘Quorum’, Gorlizki collaborates with a traditionally-trained painter from Jaipur, Riyaz Uddin, to reinterpret a group photograph from the 1880s by Raja Deen Dayal of the Maharaja of Bundi and his courtiers, which illustrates Deepali’s view that “a work can go back and forth many times before deemed complete [p. 119].” Sumathi Ramaswamy in her book opines on similar ground, stating that, “no visual image is self-sufficient, bounded, insulated; instead, it is open, porous, permeable, and ever available for appropriation,[1]” thus resulting in the creation of an ‘interocular’ or ‘intervisual’ piece of artwork.

More details about the artists and studios still working in the photographic medium in India would have been informative for readers.

An examination into the family archive of the Mohammed-Hadi-Kazmi family based in Hyderabad, Delhi, and Toronto further demonstrates the ‘transcultural’ nature of the production and circulation of Indian painted photographs, an approach that has constantly been established throughout this article by examples cited from ROM’s collection.

According to Dewan, “the continued centrality of photographic indexicality, has framed painted photography as marginal to the history of photography and as a product of local conditions [p. 33].” In India, the painted photograph took regional manifestations, as embodied in the images produced by the Nathdwara/Mewar School in Rajasthan, along with other regional centres. This eventually led to the rise of a ‘popular’ visual culture arising out of inventive and sociological transformations.

A second essay, by Olga Zotova, a photographer and photograph conservator who did her master’s research on the same theme, reviews the use of color as a form of photographic manipulation. Through her essay she tries to examine the practice of painting on the photographic image as one among a number of ways the photographic surface was manipulated from its early history onwards and argues that the manipulation of the photographic image was central to the early practice of photography.

According to her, “the desire to manipulate the photographic image stemmed from what was perceived as the limitations of photography’s technical capabilities [p. 38].” This resulted in various forms of manipulations, such as cropping, composite printing, scratching out, over-painting, retouching, and tinting, among others.

With reference to color and the photographic surface, Zotova gives some technical details about the role and functions of photographic emulsion. In India, as in Japan, painted photographs were the result of a deep visual tradition. The new medium of photography was quickly absorbed into existing image production forms and mechanisms (such as miniature painting in India and woodblock printing in Japan). She points to an interesting example of how Japanese photo studios in the nineteenth century excelled in hand-tinted portraits and landscapes. Before the invention of a photosensitive emulsion, these photo studios preferred to use tints that allowed the photographic print to show through. And unlike in India, where during the initial years hand tinted images mainly catered to the needs of the princely and elite classes, colouring of images in Japan “seems to have been driven solely by tourist demand for such imagery [p. 41]. “

Zotova concludes by aptly summarizing the nature and essence of the works chosen to be published in the catalogue.

Although a map of India has been given at the beginning of the catalogue, it fails to highlight the various regional centres or studios referred to in the text.

Unfortunately, the tradition of hand-colouring practiced by commercial studios in India has almost disappeared with the advent of colour photography and digital imagery. Only a handful of ‘artist-photographers’ can still be found in the country, thus highlighting the significance of the ROM images.

Jennifer Chowdhry is a Research Scholar with the Alkazi Foundation of the Arts, New Delhi. She holds a master’s degree in Museology from the National Museum Institute, New Delhi, and has a keen interest in the history and theory of photography. She has contributed to Journal of Indian Museums and Art: News & Views.

Notes

1. Sumathi Ramaswamy, ed., Beyond Appearances: Visual Practices and Ideologies in Modern India (New Delhi: Sage, 2003) p. 16.