Liu Heung Shing, China in Revolution: The Road to 1911 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011) 415 p. ISBN 978-988-8139-50-7

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

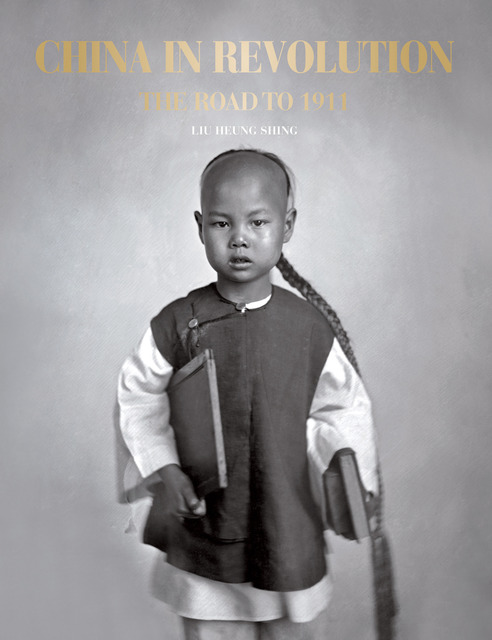

The 1911 revolution in China received renewed interest in its centenary year, 2011. A wave of new publications celebrated the centennial by recounting or reflecting on this watershed historical moment marking the overthrow of the last imperial dynasty and the birth of the Republic in China. The eminent photographer Liu Heung Shing joined the commemoration with China in Revolution: the Road to 1911, an ambitious collection of historical photographs chronicling the history of modern China. Those who pick up China in Revolution will be struck by the soft gaze of a little schoolboy on its front cover, and will later encounter the confident eyes of a soldier standing upright in modern military uniform as they close the book. Framed by these two individuals, whose names are lost to history, Liu’s volume not only supplements modern Chinese history with a visual narrative, but also reminds readers how photography could challenge, enrich, and open up the writing of history.

Liu begins the volume with an introductory article that anchors his project in the contemporary public debates about history. Wary of nationalist sentiments occasionally sweeping China that tend to frame the country’s modern history as a series of humiliations caused by imperialism, Liu urges readers to avoid a reductive interpretation when approaching the photographs, despite their rise from the context of imperialist aggression or their reflections of the eroticizing gaze of foreign photographers. Liu’s concerns echo the development of historical studies for the past decades. He invites three renowned historians to share their views: Zhang Haipeng from China emphasizes foreign aggression as the main cause of the revolution; Max K. W. Huang from Taiwan brings attention to revisionist accounts of recent years, particularly the importance of the “intellectual fermentation” of ideas, such as a democratic republic; and Joseph W. Esherick from the United States provides a lucid outline of how the initially capable Manchu rule collapsed in 1911. Their varied perspectives more or less reflect the methodological thrusts of their scholarly communities, each belonging to a geopolitical body with differing stakes in the aftermath of the 1911. Liu’s incorporation of voices from three institutions echoes his call for a nuanced and balanced approach to historical narrative.

The body of this volume consists of more than 300 photographs arranged in five sections: the Second Opium War (1856-1860), the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), the Boxer Rebellion (1898-1903), the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the Wuchang Uprising (1911), and the Warlord Era (1912-1928). Although the section titles draw attention to dramatic incidents such as wars, rebellions, and revolution, the photographs included capture a wider range of subjects. In addition to battlefields, drills, executions, and treaty negotiations, readers are offered glimpses of modern China’s conditions in agriculture, industry, education, commerce, transportation, architecture, entertainment, customs, and fashion. Most of the photographs are accompanied by captions, detailing photographers’ names and dates whenever possible, as well as names of collections where the images are held. For some photographs, the author includes brief explanations of the subject or its historical background. Many pages contain quotes from a wide variety of figures ranging from Aristotle to Sun Yat-sen, although the relationship between the quotes and photographs often seems more suggestive than informative.

This volume concludes with a timeline, an acknowledgement listing the collections that contributed images, an index of photographers, and a bibliography, all consisting of useful information to facilitate further exploration.

It is no exaggeration to say that Liu traveled the world to conduct the research for this volume. Despite the “old photo craze” (lao zhaopian re 老照片热) in China that has encouraged a great number of collectors and aficionados, a major public collection of historic photographs has yet to appear. While many overseas institutions have China photographs in their collections, there is no users’ guide to assist researchers. Liu’s multi-continent survey of this largely uncharted domain was determinedly ambitious. His effort proves to be worthwhile, as this volume showcases exciting new discoveries, many of which are published here for the first time. Notably, collections that have yet to receive recognition for their holdings of photographs on China, such as the German Federal Archives in Koblenz, Germany, are also incorporated. The booming private collections, such as that of Wang Qiuhang, Qin Feng, Wang Yulong, and the San Ren Xing Antique Photo Gallery, contribute some of the most stunning and poignant images to this volume.

Combining these unseen photographs with more familiar works such as those by Felice A. Beato and John Thomson, Liu’s selection substantially expands our knowledge of modern China. Even the 1911 revolution itself, which is relatively well-documented thanks to the fourteen volume photo book Dageming xiezhenhua 大革命写真集 [War Scenes of the Chinese Revolution] (Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1911-1912) published while the revolution was unfolding, is enriched here with photographs of the Russian medical staff handling the plague in Harbin (336-337), a rural militia in Shaanxi holding traditional weapons (334-335), and revolutionary soldiers posing for a group portrait, with happy onlookers caught in the frame (331). The visual history of modern China conjured up by Liu is multilayered, unruly, and ever evolving.

China in Revolution is not Liu’s first endeavor to record historical transitions with photographs. A Pulitzer Prize-winning photo journalist, Liu is acclaimed not only for capturing iconic moments that epitomize the drama of history, but also for illustrating profound political and economic changes with engrossing details of social lives. His early photographs were compiled into China after Mao (Penguin, 1982) and USSR: Collapse of an Empire (Asia 2000 Ltd., 1992). Although no longer actively involved in photojournalism, Liu, now living in Beijing, has embarked on a few editorial projects, such as China: Portrait of a Country (Taschen, 2008), which documents the changing country from 1949 to the present through the works of Chinese photographers.

Liu views his role as a photographer and an author-editor similarly. Whether capturing a powerful shot through the lens or selecting a worthy photograph from archives, his task requires an intuitive recognition of visual appeal as well as a clear, and oftentimes, personal, understanding of history. Liu’s historical contemplation of the 1911 Revolution is underlined by his great concern that the understanding of modern China might be trapped in the narrative of victimhood that imposes a static boundary between China and the world on both historic narrative and contemporary thought. China in Revolution refutes such oversimplification with photographic images that embody rich layers of information: the Imperial Reform Army organized by Kang Youwei’s Emperor Protection Society in the United States training in California (250-253); a Chinese boy holding a crescent-shaped halberd proudly posing among a group of Russian army officers (278-279); and villagers in northwestern China lining up with smiling curiosity as they listen to a phonograph (368). These photographs are intriguing and baffling at the same time. Minute details attest to the existence of a past that challenges binary interpretive frames such as West versus China, modern versus tradition, or agency versus passivity.

Photographers, as we are told by Seigfried Kracauer and reminded by Alan Trachtenberg, are not so different from historians, as both “...make the random, fragmentary, and accidental details of everyday existence meaningful without loss of the details themselves, without sacrifice of concrete particulars on the altar of abstraction.”[1] Looking closely at the soldier on the back cover, the reader will notice a small pin fastening his collars. Yet it is hard to say whether that pin reflects an aspiration to achieve a pressed modern military look, hints at the difficulty in achieving such a look, or alludes to the local requirements for military men. Such details lead to new lines of historical inquiry. It is the attention and commitment to details—crucial to both photography and history—that distinguish China in Revolution as a valuable addition to studies of modern China and photography.

Yi GU is an Assistant Professor, Department of Arts, Culture and Media, University of Toronto Scarborough, and Graduate Department of Art, University of Toronto.