Quick Time: On Beijing, Spring Festival and the Photographs of Hedda Hammer Morrison

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Winter in Beijing is ice cold and dry. Dusty winds blast the skin and, if you are lucky, cleanse the atmosphere to reveal a high blue sky. Over the course of seven days prior to this year’s Spring Festival, wind transformed the sky and, with it, people’s emotions, replacing thick grey smog with a marvellously clear atmosphere. From an eighth-story window I looked out across Beijing and was reminded of the remarkable geomantic design of the former imperial city, with its flat plain protected by mountains to the north and west, and by its Great Walls.

Tall buildings are not permitted in the vicinity of the Forbidden City, in deference to the historic heartland of the capital and to protect the incumbent leaders, who live in the Lakes Palaces of the former imperial precinct, shielded from view. The elegant tiled roofs and gilded gables of the Forbidden City float amid a sea of nondescript apartment buildings, with the titanium and glass “Egg” of French architect Paul Andreu’s National Centre for the Performing Arts (opened 2007) hovering behind, and the Soviet-inspired Great Hall of the People, designed by Zhang Bo, Zhang Dongri and others (opened 1959), standing bulwark-like to its left, with festive red flags flapping in the wind. It is impossible not to feel astonished by the radical juxtaposition of these iconic buildings, markers of the extraordinary cultural transformations that have taken place in Beijing during the last century, effectively melding imperial, socialist and global-contemporary time.

Walking in and around the Forbidden City (now the Palace Museum), Tiananmen Square and what remains of Beijing’s laneways or hutong, it is hard not to think of Hedda Hammer Morrison’s photographs, created more than seventy years ago, during her thirteen year period of residence in the city. Morrison recorded the city and the lives of its people in a more focussed way than perhaps any other resident photographer, creating a rich visual archive.

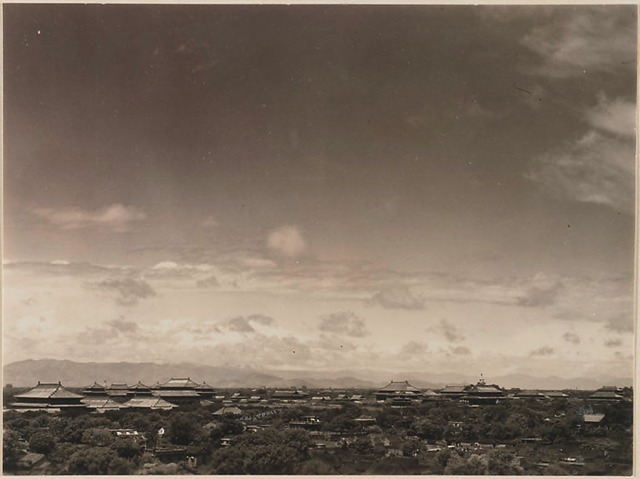

In one of her panorama-like photographs of the Forbidden City, center of the imperial city and the Chinese world, the glazed tile roofs reach heavenwards, towering over the city while retaining a sense of scale and proportion in relation to the natural and man-made environment. Morrison deliberately framed her image so that the sky takes up the majority of the field, as if to highlight the significance of heaven in relation to earth.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. Hedda Hammer Morrison (1908–1991) trained as a photographer in Germany and arrived in Beijing in 1933 to manage Hartung’s, the German-owned photography studio that was established in1912.[1] With self-taught Chinese and her own gutsy curiosity this 24 year old foreign woman explored the city by bicycle. It was probably from her small top-floor apartment in the Grand Hotel des Wagon Lits that she began to understand the layout of the city. From the roof garden of the hotel it was possible to look across to the Forbidden City.[2] Influenced by the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) that she had encountered in Germany, she sought out dramatic camera angles, climbing on top of city walls and gates, the Bell and Drum towers and Prospect Hill to find strong compositional lines that allowed her to create images at once documentary and artistic.

Morrison’s large archive of photograph albums, contact sheets and negatives was bequeathed to the Harvard-Yenching Library. The negatives are now being digitized, part of an ongoing project by the Harvard Library Collections Digitization Program and the Weissman Preservation Center to rehouse the collection and make the images accessible on the world wide web.[3] Views never before printed by Morrison are being recovered and returned to the public, many of them revealing the extent to which the imperial designs of the city have been altered and redefined.

Among the recently scanned negatives are two previously unknown bird’s-eye views of Beijing. The photographs are oddly composed and seem incomplete, as if they were intended as sections of a panorama. Taken in winter from the top of the Drum Tower, looking south, the first image leads our eye to the Gate of Earthly Peace (Dianmen), and beyond to Prospect Hill and the Forbidden City, with the frozen imperial lakes and the Beihai Dagoba to the right. The companion photograph, with the upturned lower roof of the tower on which the photographer stands thrusting into frame, looks southwest across the once ubiquitous courtyard houses to the Gate of Realized Abundance (Fuchengmen).

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.  Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. The Drum and Clock towers marked the northern end of the imperial axis, and the Gate of Earthly Peace (Dianmen) was the northern gate of the former Imperial City. As Wu Hung has observed, “the area outside Dianmen was a public space populated by the subjects of imperial rule, while Tiananmen symbolised the Emperor as Master of the whole population”.[4] In 1955–6 The Gate of Earthly Peace was demolished, leaving its counterpart, The Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tiananmen), alone and out of balance.

In a striking photograph of the Gate of Heavenly Peace, taken not long after Morrison arrived in Beijing, the ornate carved marble column or huabiao is in its original position (the four huabiao were moved in the 1950s as part of the expansion of Tiananmen Square). A clock marking Republican time stands above the railing, announcing a temporal shift. It was removed in 1937 and later replaced by a standard portrait of Mao Zedong, marking the formal place and time of the founding of the Communist government.[5] Today, an updated portrait of Mao Zedong continues to hang in that same location, facing the flag of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as it is raised each morning in the Square in a formal military ceremony. Above the portrait is the crest of the PRC which hangs under the glazed eave of the Gate, replacing the ornate board that once named the building, originally written in Chinese and Manchu, the language of the Qing emperors.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, 1933–37,© President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, 1933–37,© President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. A decade before Mao Zedong stood on the rostrum of Tiananmen and announced the formation of the Central People’s Government, Morrison stood in a similar position looking down on the trees and walled enclosure of the Imperial Passageway that would be razed to make way for Tiananmen Square. Her photograph gives a clear uninterrupted view along the Imperial Passage to the Front Gate (Zhengyangmen). The reverse view, from the top of Zhengyangmen looking north towards Tiananmen, is also provided. The China Gate (Zhonghuamen) stands prominently in the mid ground. It was originally called the Gate of the Great Qing, and before that the Gate of the Great Ming, and was demolished in 1958 to make way for the Monument to the People’s Heroes.[6]

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.  Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. From the Gate of Heavenly Peace the visitor approaches Meridian Gate (Wumen), one of the formal entrances to the Palace Museum, and in Hedda Morrison’s time, the entrance to the National History Museum. Today, a military troop tasked to protect the national flag that is raised there each morning is stationed in a faux palace–style building with large reflecting glass windows that only allow those inside to see out. The military area is further delineated by a drill ground carpeted with artificial grass and a large billboard extolling the words of President Hu Jintao: “ Follow the Party’s Commands; Serve the People; Be brave and skillful in battle” (22 October 2006). The former palace is today “home” to many military troops who reside in secluded zones behind high walls, and in “screen buildings” with fake palace roofs, originally built along the Western perimeter to prevent residents of the seven-story Peking Hotel from peering down into the Communist Party leadership compounds in the nearby Lakes Palaces.[7]

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. Passing through the Meridian Gate and the Gate of Supreme Harmony (Taihemen) the visitor reaches the main hall of the outer court where important ceremonies, such as lunar New Year, enthronements, birthdays and sending generals into battle, were once held. The approach to the three-tiered white marble base of the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihedian) is flanked by two large bronze signs with explanatory texts in Chinese and English with the credit line “Made possible by the American Express Company”. In Hedda Morrison’s photograph of the southern façade of the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the expansive courtyard is empty but for a healthy covering of grass. In 1938 Morrison moved into a courtyard house in Long Street South (Nanchangjie), not far from the western entrance to the Palace at West Flourishing Gate (Xihuamen, now used as an access point for the Central Guard Bureau, a military unit occupying the southern screen building). The Forbidden City and Lakes Palaces of the Southern, Central and Northern Seas (Nanhai, Zhonghai, Beihai) were close by, and became important subjects for her photography. She was able to get there in the early morning or late afternoon, when there was good light and few people were around.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

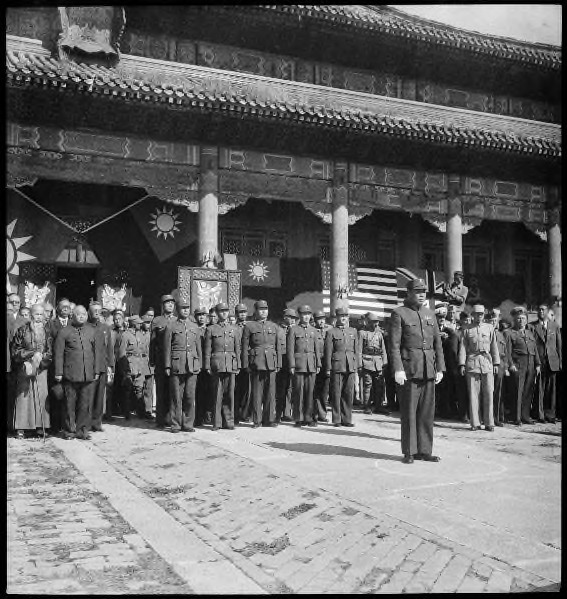

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. Morrison was not a photojournalist and her archive contains relatively few photographs of topical or newsworthy events. Her proximity to the Forbidden City may in part explain a series of photographs that record the official ceremony in Beijing before the Hall of Supreme Harmony on October 10, 1945 to mark Japan’s surrender in the Sino-Japanese war. After the United States dropped bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki the Japanese Emperor announced the surrender of Japan on August 15, and on September 9 the Act of Surrender for the war in China was signed in Nanjing, then the capital. It is not known who commissioned Morrison to take the photographs, but her prominent position on the forecourt of the Hall of Supreme Harmony indicates her official capacity. She photographed the Chinese military delegation making their way along the imperial axis to the Hall of Supreme Harmony, surrounded by a huge crowd of locals assembled in the courtyard to bear witness to the historic occasion. Entry to the Forbidden City that day was free. In other photographs she focuses on the leader of the Chinese military delegation Sun Lianzhong, who stands at attention during the flag raising ceremony with American and British military dignitaries in the background; the signing of surrender documents by the Chinese and Japanese representatives; and the crowd of locals milling in the grass-covered courtyard, with a curious onlooker visible at the edge of the frame.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.  Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, October 10, 1945, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, October 10, 1945, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.  Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.  Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.  Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, October 10, 1945, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. For Morrison the surrender ceremony had a particular significance. Germany had also surrendered on May 7. Morrison had left her native Germany in 1933 with no intention of returning. Yet the situation in China was unstable and quickly descended into civil war. After Morrison’s contract at Hartung’s Photo Shop finished in 1938 she stayed on in Beijing and worked as a freelance photographer, piecing together a living. In 1941 she met Alastair Morrison when he visited Peking. He joined the British Embassy to work in intelligence, and during the war was evacuated to Kolkata, then posted to Chungking and Malaya. Alastair Morrison (1915–2009) was born in Peking. His father, George Ernest Morrison (1862–1920), was the famous “Morrison of Peking”, the London Times correspondent in China who later became political adviser to Yuan Shikai, the self-negotiated President of the Republic. After the surrender of Japan, Alastair Morrison was posted to Shanghai and took leave from the army to return to Peking, where he and Hedda were married in July 1946. With a newly issued passport, Mrs. Hedda Morrison, now a “British subject by marriage, wife of a British subject by birth”, could travel to Hong Kong and begin a new phase of her life.

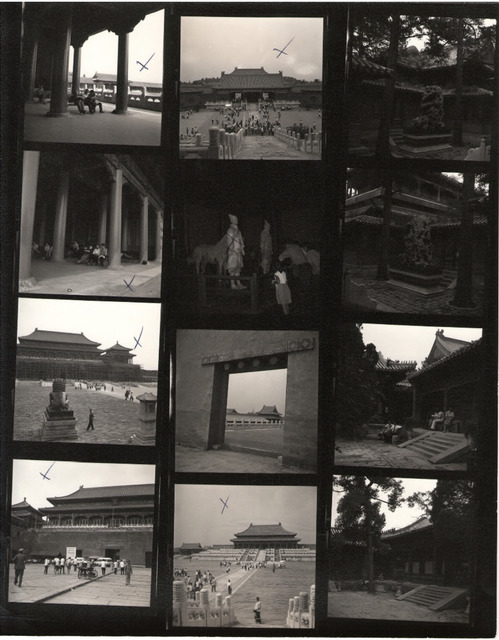

Thirty years would pass before Hedda Morrison returned to China, as a member of an Australia-China Friendship Society travel group.[8] Contact sheets of photographs that she took during that visit in 1979 (she made subsequent trips in 1982 and 1987) include images of the Meridian Gate and the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City, as well as the newly constructed Chairman Mao Memorial Hall (1977), with people queuing to see the embalmed body of Mao Zedong. In the postscript to the book A Photographer in Old Peking (1985), she wrote: “The changes that had taken place were enormous...The Peking that I knew is now no more than the core of a huge metropolis spreading out in every direction to cover what used to be agricultural land. There has been large-scale industrialisation and nowadays when you look out from cherished viewpoints of times past you see a panorama of innumerable multi-story buildings punctuated by tall factory chimneys belching smoke. The splendid city walls have been razed and the moat filled to provide for a ring road. The brilliant north China light has lost its shine to a layer of smog”.[9]

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.  Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University.

Hedda Hammer Morrison, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Courtesy the Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. On my way back to the hotel after visiting Tiananmen Square I took note of the silk banners that lined the streets for the Spring Festival, celebrating the Year of the Dragon. The traditional character “Fu” meaning happiness and luck was paired with the phrase “Standing on a new launching pad, Make a new leap forward”. Looking out of my window early on the morning of Spring Festival eve, the new headquarters of China Central Television, designed by Dutch architects Rem Koolhaus and Ole Scheeren (opened 2009) featured prominently on the skyline. Locals refer to it as ‘the big pair of pants’. Its ungainly form, like a pair of striding legs making a new leap forward, emitted a plume of steam, the hot air condensing in the cold clear atmosphere. After establishing that “the pants” were not on fire (in 2009 the building was badly damaged by fireworks let off to celebrate the end of the lunar new year holiday), I found it to be a humorous sight, a sign of the water dragon stirring to life after a sixty-year slumber (the last water dragon year was 1952), readying himself to reign over the Chinese world in 2012.

Dr. Claire Roberts is Senior Lecturer in the Art History Program, School of History and Politics, at the University of Adelaide, Australia.

Notes

See Claire Roberts, ‘In Her View: Hedda Morrison’s Photographs of Peking, 1933–46’, East Asian History 4 (1992): 81–104, and Alastair Morrison, ‘Hedda Morrison in Peking: A Personal Recollection’, East Asian History 4 (1992): 105–114.

See Geremie R. Barmé, The Forbidden City, Profile Books, London, 2008, p. 160

See Harvard University’s Visual Information Access website http://hcl.harvard.edu/libraries/harvard-yenching/collections/morrison/

As a research fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University (2009–10) and as a Coordinate Research Fellow working with Dr. Raymond Lum , Curator of Photographs at the Harvard-Yenching Library (2011), I worked closely with colleagues in the library, digitization program and Weissman Preservation Centre on this project and am grateful for their support with my research into the Hedda Hammer Morrison archive. In particular I would like to thank Raymond Lum, Maggie Hale, Robert Burton, Brenda Bernier and Zachary Long.

Wu Hung, Remaking Beijing: Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2005, p. 147.

Portraits of Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek, earlier twentieth century leaders, had also hung there. I am grateful to Sang Ye for information about the clock and other details in some of the photographs.

For information about the Lakes Palaces and ‘screen buildings’, see Geremie R. Barmé, The Forbidden City, pp. 150–162.

Hedda Morrison returned briefly in 1948 to collect her remaining belongings. See Hedda Morrison, ‘Postscript’, in A Photographer In Old Peking (Oxford University Press, Hong Kong, 1985) p. 259