Okinawa-Philadelphia-Tokyo: The Specificity and Complexity of Mao Ishikawa’s Photographic Work

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Mao Ishikawa’s February 2012 Shows:

- Yokohama Museum of Art, Dec. 17, 2011 – Mar.18, 2012

- Photo City Sagamihara 2011 Nikon Salon, Nishi-Shinjuku, Jan. 31 – Feb. 13, 2012

- A Port Town Elegy Photographers’ Gallery, Tokyo Feb. 1 – 17, 2012

- Here’s What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, Zen Foto Gallery, Feb. 3 – 26, 2012

Over the months of February and March 2012, Mao Ishikawa’s photography was on view at four different exhibition venues around Tokyo’s metropolitan area. First, Ishikawa’s one person show, “A Port Town Elegy” was on view at the Photographers’ Gallery in Shinjuku; just across the tracks on the Western part of Shinjuku town, Ishikawa took part in a group exhibition at Nikon Salon entitled Document! Express! Memory!, in which she showed her series “Fences: Okinawa”; a couple of weeks later Zen Foto Gallery chose to display Ishikawa’s “My View of the Japanese Flag” series, while the Yokohama Museum of Art had Ishikawa’s “Okinawa Soul” series on view.

Mao Ishikawa, “A Marine airplane landing at Futenma Air Base. July 2009, Ginowan City, Okinawa”, from the Fences series, © Mao Ishikawa.

Mao Ishikawa, “A Marine airplane landing at Futenma Air Base. July 2009, Ginowan City, Okinawa”, from the Fences series, © Mao Ishikawa. This enormous amount of work on display marks the rocketing presence of Ishikawa in the contemporary Japanese photography scene, following many years in obscurity, with little acknowledgement of the exciting and moving quality of her work.

Mao Ishikawa was born in 1953 in Ôgimi Village, in the northern part of Okinawa, one of the most distant and rural areas of Japan. When Ishikawa was born, Okinawa was officially taken from Japanese hands and put under the control of American military forces, a status that remained in effect until her graduation from high school. By that time, in 1972, Okinawa went back to being under the full political command of Japanese authorities.

Mao Ishikawa, “Ms. Wakana Ohshiro (26) A student of a drama school June 8, 2008, in Nago City, Okinawa”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.“Being engulfed by the waves and gasping for breath, I am expecting my mind to move forward through the struggle. I have just been living an enjoyable life up until now. There are some children who are just standing still, but I am not. I want to move forward with the children in Nago and those in Japan. I feel easy and relieved in the ocean for some unknown reason.”

Mao Ishikawa, “Ms. Wakana Ohshiro (26) A student of a drama school June 8, 2008, in Nago City, Okinawa”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.“Being engulfed by the waves and gasping for breath, I am expecting my mind to move forward through the struggle. I have just been living an enjoyable life up until now. There are some children who are just standing still, but I am not. I want to move forward with the children in Nago and those in Japan. I feel easy and relieved in the ocean for some unknown reason.”However, growing up in such split and controversial situation powerfully affected Ishikawa’s personal experience of Japan, and raised the question of what it meant for her to be “Japanese.”[1] A disputed area, Okinawa, (also known as the independent kingdom of Ryukyu Islands until 1879) is a group of islands that lies south of Japan, close to the island of Taiwan and the east coasts of China. The territory was annexed by Japan in the early Meiji period, along with the settlement process in the northern terrain of Hokkaido Island. Both areas marked the beginning of Japan’s desire for colonial expansion into new territories, a process which continued, with the invasions of China, Korea, Manchuria and other countries in Southeast Asia, over the first part of Showa period (1925–1945). The end of WW2 marked the end of Japanese colonialism in Asia, with the infamous bloody Battle of Okinawa, involving huge numbers of civilian deaths, ending with the stationing of US military bases in the area. This was the end of the annexation chapter, when the controversy over the political, social and cultural status of the islands seemed to begin.

Mao Ishikawa, “Mr. Keiichi Takeuchi (33) A writer of manners and customs Tomoko (31) Ryuh-sei (18 days) May 24, 2009, in Tokyo”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.“A child was born in this country. Wrapped in the national flag, he is crying vigorously. His father and mother are protecting and supporting him. There are people who love or hate the Rising-Sun flag. Embracing everything, we want the child to move forward. Everybody is being embraced. It may be no concern of the child.”

Mao Ishikawa, “Mr. Keiichi Takeuchi (33) A writer of manners and customs Tomoko (31) Ryuh-sei (18 days) May 24, 2009, in Tokyo”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.“A child was born in this country. Wrapped in the national flag, he is crying vigorously. His father and mother are protecting and supporting him. There are people who love or hate the Rising-Sun flag. Embracing everything, we want the child to move forward. Everybody is being embraced. It may be no concern of the child.”Mao Ishikawa was born into this unsettled situation and spent her youth between military zones, in fenced territories, and under the constant demand of Japanese political and cultural agents to redesign Okinawan consciousness along mainstream Japanese lines. All these rather difficult and unsettling phenomena form the background of Ishikawa’s work, accompanied by the daily life struggle of the local impoverished communities, the significant presence of American G.I.s and an overall sense of only partially fitting in to Japan’ s conventional culture.

Ishikawa started her photography career in a workshop guided by the famous Japanese photographer Tômatsu Shômei (b. 1930), in Tokyo in 1973, when she was 20. Tômatsu’s strong, vivid, direct style of documentary photography was a starting reference for Ishikawa, who poignantly, sharply and fearlessly directed her camera towards herself, her friends, acquaintances, neighbors, fellow city dwellers, and the American G.I.s. In her first series that burst into public attention, “A Hot Day in Camp Hansen”, Ishikawa documented the intimate circle of her female friends, most of whom worked as bar hostesses, and their G.I. boyfriends, lovers or acquaintances. This intensive and thought-provoking series, made between 1975–7, bravely displayed forbidden relationships between the local girls, experiencing the poverty and isolation of their location, befriending the American G.I.s who, on one hand, signalled the far away, powerful and the exotic world of America, and yet, were often themselves victims of the American system.[2] Many of the men involved in the photographs came from poverty stricken areas, faced social and financial barriers, and used their military service as a launching pad to a better life in the US.

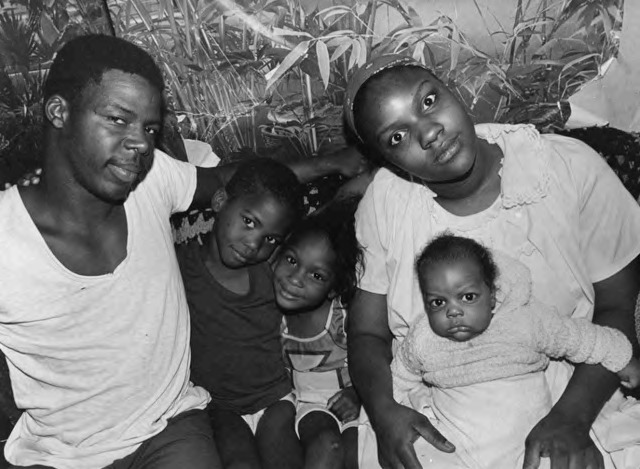

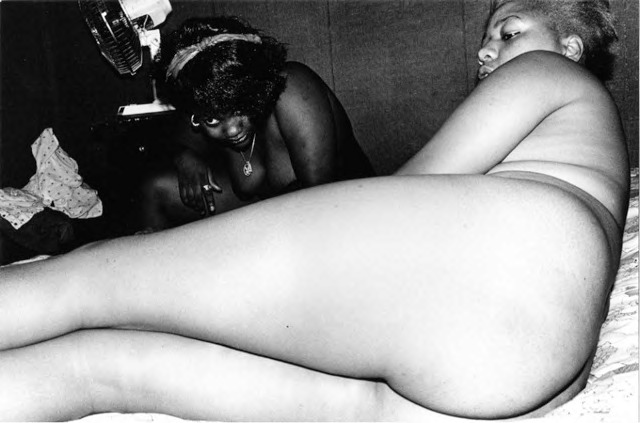

In another significant, intimate and powerful series that was shot in Philadelphia in 1986, Ishikawa travelled for the first time to the US to visit her friend Myron Carr, a US soldier who Ishikawa had first met in 1975 when she started taking photos in the Koza bar. During the two months of her stay in Philadelphia, Ishikawa documented the lives and surroundings of Myron and his friends, 11 years after his departure from Okinawa.

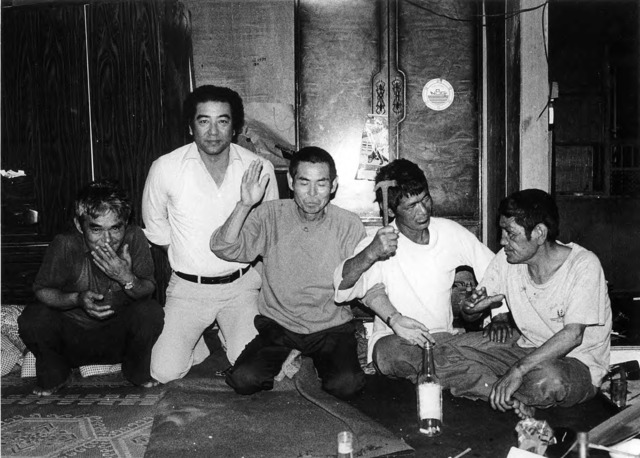

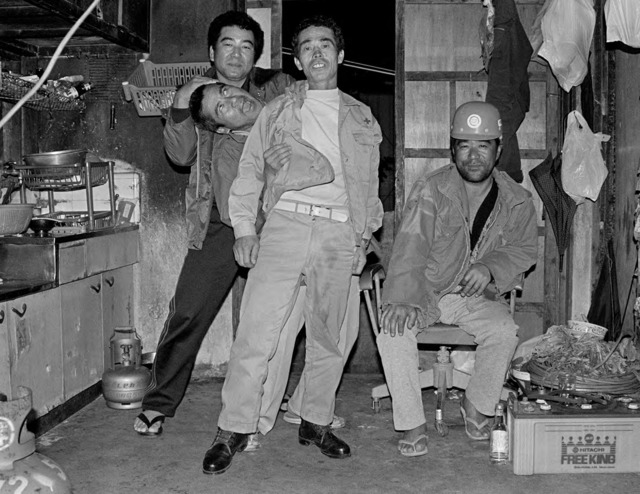

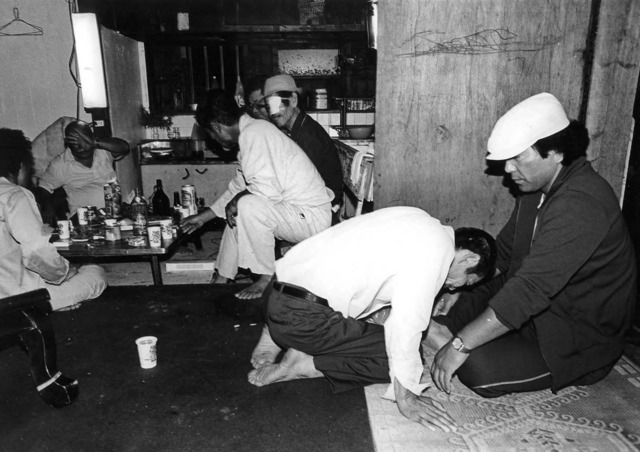

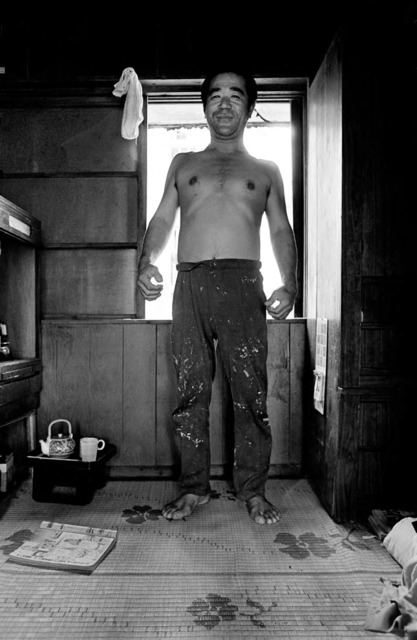

The current projects displayed by Ishikawa bring a further expansion of her working strategies, spaces of encounter and fields of interest. In the Photographers’ Gallery, Ishikawa showed “A Port Town Elegy”, a series of black-and-white photographs (most of her work is in black-and-white), taken between 1983–6 at ya-gua (“The Haunted House”), displaying the meeting place of a group of men. Most of these men are laborers, dock workers, or fishermen; others are unemployed or homeless. They come to meet here, enjoy a drink, sing loudly the old ballads of Akagi Keiichiro, and perform rituals of male friendship, says Ishikawa.[3]

The smiling faces and nonchalant bodily gestures of the of the aging, worn out working class men relaxing after-hours, combined with derelict meeting area with its the bottles of beer, and dark and gloomy atmosphere give the images a haunting quality. A new level of intimacy and indirect contact between the viewer and the subject is achieved, to a level bordering on voyeurism. The momentary enjoyment of an evening drinking and meeting with friends occupies the photographs in a manner that echoes her previous projects such as “A Hot Day in Camp Hansen” or “Life in Philly”.

Mao Ishikawa, “Catching cicadas along the Futenma Air Base fence line. August 2009. Ginowan City, Okinawa”, from the Fences series, ©Mao Ishikawa.

Mao Ishikawa, “Catching cicadas along the Futenma Air Base fence line. August 2009. Ginowan City, Okinawa”, from the Fences series, ©Mao Ishikawa. The pictures shown at Nikon Salon mark Ishikawa’s successful landing into the mainstream photography arena of Japan, winning this year’s Grand Prize. Here, images from her highly praised series “Fences”become Ishikawa’s metaphor for Okinawa’s state of affairs. The fences in Ishikawa’s work signify the boundaries or, more accurately, the limitations of space, which stand at the core of her photographic work.

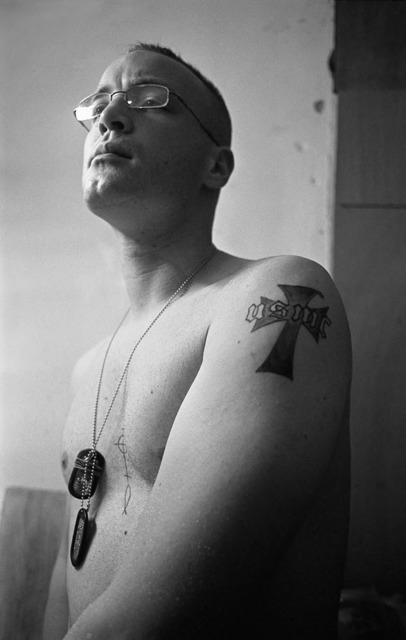

Mao Ishikawa, “Military I. D. tags or ‘Dog Tags’ worn at all times. December 2009. Kin Town, Okinawa”, from the Fences series, ©Mao Ishikawa.

Mao Ishikawa, “Military I. D. tags or ‘Dog Tags’ worn at all times. December 2009. Kin Town, Okinawa”, from the Fences series, ©Mao Ishikawa. Rather than the personalities or identities that inform the majority of her previous series, in “Fences”, Ishikawa distressingly displays the complex situation of Okinawa’s islands, which are criss-crossed by fences, blockades, barriers and other forms of boundaries. Ishikawa brings the viewer closer to understanding the complexity of space and time, and the intricacy of movement, in an area which is designed by political forces and contradictory ambitions, shaping people’s lives and routines beyond personal need or individual desire.

Mao Ishikawa, “Ms. Kim Manri (54) An artistic director of Performance Troupe 'TAIHEN' December 7, 2007, Osaka City, Osaka”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.Manri is a seriously disabled person whose whole body under the neck is paralyzed due to polio. “There is an expression, 'The white of the Rising-Sun flag is the bone of the masses and the red is blood.’ That’s it. I am opposed to cruel wars, but we still have to watch brutality among human beings. I felt sad after the performance. I do not want to see the Rising-Sun flag nor do I want to touch it.”

Mao Ishikawa, “Ms. Kim Manri (54) An artistic director of Performance Troupe 'TAIHEN' December 7, 2007, Osaka City, Osaka”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.Manri is a seriously disabled person whose whole body under the neck is paralyzed due to polio. “There is an expression, 'The white of the Rising-Sun flag is the bone of the masses and the red is blood.’ That’s it. I am opposed to cruel wars, but we still have to watch brutality among human beings. I felt sad after the performance. I do not want to see the Rising-Sun flag nor do I want to touch it.”The last series on display at this time in Tokyo was significantly different in strategy and result from the other groups on view: Zen Foto Gallery showed Ishikawa’s flag project under the title “Here’s What the Japanese Flag Means to Me”. Ishikawa worked on this project between 1993–1999 within Japan, producing 100 images that were then published in a magazine. But in 2007 she decided to expand the project and take pictures also outside of Japan, and by 2010, she produced another 84 images. Ishikawa first asked her friends and those close to her, and later approached people overseas and in foreign territories to interact with the Japanese flag in some meaningful way for them. She left the matter completely in the hands of her chosen subjects, and served their desire to be photographed in certain positions or circumstances that reflected their emotions towards the symbol of Japan as an independent state, as well as an empire and colonial power in Asia’s past.

Mao Ishikawa, “Ms. Yugi Yoshino (26) A graduate student of Ritsumeikan University November 9, 2009, in Kyoto”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.Yugi is a plaintiff who filed suit for medical malpractice regarding gender identity disorder. “In 2006, I had surgery on my breasts at the Osaka Medical College Hospital, and too much excision caused necrosis. I filed suit, and a reconciliation offer is to be made soon. The reason I straddled the Rising-Sun flag cut in half is that students are divided in two on the peace problem. I painted the scars on my breasts ‘the red of the Rising-Sun flag’. What gruesome drippings! Handcuffs show the terror of ‘the Rising-Sun flag’ and Kimigayo putting people into prison.” (Note: Yugi won the case in March, 2010.)

Mao Ishikawa, “Ms. Yugi Yoshino (26) A graduate student of Ritsumeikan University November 9, 2009, in Kyoto”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.Yugi is a plaintiff who filed suit for medical malpractice regarding gender identity disorder. “In 2006, I had surgery on my breasts at the Osaka Medical College Hospital, and too much excision caused necrosis. I filed suit, and a reconciliation offer is to be made soon. The reason I straddled the Rising-Sun flag cut in half is that students are divided in two on the peace problem. I painted the scars on my breasts ‘the red of the Rising-Sun flag’. What gruesome drippings! Handcuffs show the terror of ‘the Rising-Sun flag’ and Kimigayo putting people into prison.” (Note: Yugi won the case in March, 2010.)Later, Ishikawa interviewed her protagonists, asking them for the particular reasons why they chose a specific set-up, performance or interaction with the Japanese hi-no-maru flag. About 80 of these photographs were published in a book, while some 20 images were on display at the gallery. Although, in this project, Ishikawa departed from her documentary practice, moving towards a more conceptual and staged working method, her ability to create intimacy and closeness with her subjects, as well as her direct and frank engagement with a subject so loaded and significant to herself, make this series of images very substantial and emotional. The range of sentiments expressed towards the object symbolizing Japanese authority range from identification and affection to hatred and violence; from sensuality and connection to estrangement and ferocity. It is also important that the pictures were shot in color, making the red circle of the Japanese sun a crucial presence that links the images to one another in a visual, typological manner.

Mao Ishikawa, “Ms. Morika Yoshiyama (20) A temporary worker in a public office November 29, 2009, in Nakagusuku Village, Okinawa”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.“In my third year of high school, I felt the teachers were forcing education on me. I hated it, and I imprisoned myself in my home. I am wearing the school uniform because I was robbed of youth in my high school days. I feel that, deep down in the Rising-Sun flag, there lie blood and corpses. The ruins are an expression of my heart. I feel I am being watched even at this moment.”

Mao Ishikawa, “Ms. Morika Yoshiyama (20) A temporary worker in a public office November 29, 2009, in Nakagusuku Village, Okinawa”, from the series Here Is What the Japanese Flag Means to Me, ©Mao Ishikawa.“In my third year of high school, I felt the teachers were forcing education on me. I hated it, and I imprisoned myself in my home. I am wearing the school uniform because I was robbed of youth in my high school days. I feel that, deep down in the Rising-Sun flag, there lie blood and corpses. The ruins are an expression of my heart. I feel I am being watched even at this moment.”To summarize, Ishikawa’s current shows and her previous exhibitions and books reveal a photographer of great sensitivity, with strong emotional connections to her subjects. Beyond its significant human quality, Ishikawa’s work is politically charged, contesting commonly accepted ideas of Japan, and in fact revealing an unknown Japan, a land that exists beyond the bustling, expensive metropolitan areas of Tokyo and other major cities, or the old traditional rural sites. Ishikawa’s photographs pose a real challenge to the edges of Japanese identity, stretch the prominent concept of Japanese “homogeneity” beyond its accepted limitations, and display a world of sensuality, vitality and extended refusal to easily submit to long-standing conventions of Japanese-ness.

Ayelet Zohar is an artist, independent curator and visual culture researcher specializing in Japanese photography. Zohar teaches at the department of Asian Studies at Hebrew University and the University of Haifa, and has published an exhibition catalogue and an edited volume under the title: PostGender: Gender, Sexuality and Performativity in Contemporary Japanese Art/Culture (2005 and 2009 respectively). She is on the Editorial Board of the TAP Review.

Notes

1. Ishikawa Mao, Okinawa Soul 《沖縄 ソウル》Taita Publishing, 2002, pp.16–7.

2. Taro Amano, The Personal History of a Photographer, Mao Ishikawa, and the History of Okinawa Yokohama Museum of Art, 2011

3. An extract from Ishikawa’s exhibition communicate, Photographers’ Gallery, Tokyo, Feb. 2012.