John Thomas Gulick (1832-1923) - Pioneer Photographer in Japan

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Introduction

John Thomas Gulick, a member of the famous Gulick missionary family of Hawaii, was also a respected biologist who contributed much to the post-Darwinian debate on evolution. An amateur photographer, he spent eighteen months in Japan during 1862 and 63 and made an important contribution to the development of photography in that country. He instructed the Reverend Samuel Robbins Brown in the art, was an early photographer in Edo (Tokyo) and taught at least one early Japanese photographer. Although further research is required, it seems likely that this photographer was Shimooka Renjo, a famous Japanese professional photographer who opened his first studio in Yokohama in 1862. Past research had indicated that Shimooka took lessons from the Reverend Samuel Brown, or even his daughter, Julia, who would herself become an enthusiastic photographer. This article throws doubt on these theories, and instead suggests that Gulick should be considered a strong candidate.

Early Life

Gulick was the son of missionary parents, Peter Johnson Gulick and Fanny Hinckley Thomas, who served in the Hawaiian Islands under the auspices of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). It was there on the remote island of Kauai that John Thomas Gulick was born on 13 March 1832. He was the third to be born in a family of seven boys and one girl.

As a child, Gulick suffered from deficient eyesight, something that was to plague him throughout his life. In 1841, he entered the Punahou Academy, Honolulu but had to leave in 1847 due to a weak constitution exacerbated by overwork. The following year his parents decided to send him to Oregon, United States in order to recover his health. Gulick arrived in the summer of 1848 in the middle of the California Gold Rush, which he himself joined a few months later after seeking his parents’ permission. By June 1849, his prospecting was reasonably successful, but after having his money stolen, he returned to Hawaii a few months later after having recovered his finances through various trading ventures. After arriving back home in June 1850, he took his family’s advice and invested what money he had made in land in Waialua. This would prove to be a sound decision and helped support Gulick throughout the rest of his life.

At around this time, the ABCFM had decided that the Christianization of the Hawaiian people was practically complete and it encouraged its missionary members to resign and engage in secular activities. Certain financial support was offered, and Gulick helped his parents with their livestock farming business. In his spare time, he pursued a keen interest in science and developed a passion as a collector of local snails. He also travelled to the Micronesian island of Pohnpei in 1852, where he made scientific drawings of the ruined city of Nan-Matal – the first Westerner to do so.

In 1853, he read Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle and this began a lifelong interest in evolutionism. That year he left for America to undertake academic studies, and from 1853-55 he was at New York University’s Prepatory School. Thereafter, from 1855-59 he studied at Williams College where he deepened his interest in Darwin’s theories. At this time, his twin interests were evolutionary science and Christianity. He enrolled at the Union Theological Seminary in 1859 but left two years later due to eyestrain - a condition that also meant he would take no part in the Civil War. He now planned to visit Colombia to collect shells, but a revolution there brought about a change of plans. After some thought he decided to seek a missionary post in Japan – a country in which he had begun to have some interest. In his memoirs, written around 1912 (hereinafter referred to as Outline of My Life), he mentioned that in view of his poor eyesight, missionary work in Japan would be easier than in Africa or the islands of the Pacific. Why he believed this to be the case is not clear. In any case, with his destination clear he arrived in San Francisco on 5 September 1861.

While seeking a way to secure a passage to Japan he spent several months teaching in Santa Clara. Returning to San Francisco on 13 February 1862 he introduced himself, the following week, to Robert Hewson Pruyn (1815-1882), an American lawyer and politician who had been appointed US Minister to Japan and was about to leave for that country. Pruyn agreed that Gulick could accompany him to Japan but gave no guarantees of employment there. An approach to the ABCFM for missionary work in Japan was rejected, as that organization’s funds were depleted due to the Civil War. Still determined to go to Japan, Gulick gave serious thought to how he might earn his keep on arrival. He decided he might do so by taking a camera with him.

Feb 1862 ‘Commenced learning Photography with Mr. Watkins [Carleton E. Watkins (1828-1916), noted early American landscape photographer].’

This reference appeared in a journal which Gulick kept for a few months in 1862. An entry made on 1 March referred to his taking his camera and chemicals to the ABCFM. Quite why he did so is not clear, but in any case on the 15 March 1862 he left San Francisco in the Ringleader bound for Japan, travelling with Minister Pruyn. On the 27 March 1862, he arrived at Honolulu, and for a few days was temporarily reunited with his family. He refers in his journal to overhauling the photographic apparatus and chemicals with his brother, Orramel, and to purchasing Hardwick’s Photographic Chemistry. He left on the 30 March, and arrived in Japan on 24 April.

John Gulick in Japan

The following day he was a guest of the American missionary, Reverend Samuel Brown, staying at the Jōbutsuji Temple, Kanagawa.

25 April1862 [Kanagawa] ‘...A son of the Rev. Mr. Gulick of Honolulu, who arrived in the Ringleader with Mr. Pruyn has come to reside with me...’[1]

Gulick had no obvious means of financial support but was determined to pay his own way in Japan. In Outline of My Life, held by Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library, Gulick makes clear how he occupied his time:

‘During the 18 months that I remained in Japan I was supporting myself partly by tutoring in Dr. Brown’s family and partly by taking stereoscopic photographs with a small camera that I had brought with me from San Francisco...’

The same library holds a manuscript entitled In the East and the West in which Gulick writes:

‘Two hours of each day I spent in teaching Mr. Brown’s children, giving the rest of my time to photographing Japanese scenes, and studying the Japanese language.’

The following extracts from his 1862 Journal, which ended abruptly on the 7 July of that year, are most illuminating:

2 May1862 ‘At noon experimented with some of Mr Brown’s photograph chemicals which Miss [Julia] Brown supposed were out of order;succeeded in taking a poor picture.[2] Changed some of the materials and after dinner took my first portrait. It was an ambrotype of Mr Louder [sic – Lowder, John Frederick (1843-1902) a language student at the British Legation who married Julia Brown in August 1862]. It was taken when the sun was behind the hill and is therefore lacking in contrast of shades. Mr. Ostrom[3] of the Dutch Reformed Mission at Amoy has arrived this evening with his family, and they have taken the room which I have occupied the past week, and I have a room adjoining Mr. Brown’s study in Sokoje [Sokoji Temple, Kanagawa].’

This passage is interesting because it suggests that Brown had made little progress with photography at this stage and that Gulick’s help was invaluable. Indeed, he himself confirmed as much in a letter he wrote home to the Rev. Philip Feltz of the Dutch Reformed Church:

25 October 1862 [Kanagawa] ‘By the bearer, Mr. T. Hart Hyatt, I send you 42 large photographs of Japanese scenes, marked, & in parcels, to be sent to the following churches, seven to each... All these Churches contributed to purchase the apparatus & chemicals for my use. I promised them pictures from Japan, expecting Dr. Simmons to make them.[4] But as he did not, I bought last year $45 worth & sent home by a Capt. Jones, who writes me that he expressed them to Auburn as directed, but they have never been heard of since. Now to keep my promise I have learned by books, mostly, enough to take pictures myself, & here are some of the results. I have sold enough here to buy additional material at San Francisco, & so keep my stock good, & have procured the same. A brother of Dr. Gulick of the Micronesian Mission, has spent the summer here, & aided me in learning the art. I wish you to have these pictures well put up and sent to the churches above named. Besides these I have put in one for you, to show that ‘Tommy’ is not dead, as reported. He is attached to the U.S. Legation as an interpreter. Also 2 for my good friend P.C. Doremus, 2 for the Rooms of the Board, & the rest for my son in New Brunswick. They are all named and marked on the back, as you will see.[5]

Gulick’s 1862 Journal continues:

3 May1862 (Saturday) ‘The children do not recite lessons on Saturday; accordingly I have determined to make that my day for photographic operations. I have to-day unpacked my instrument & chemicals. I have the use of Mr. Brown’s Daguerean Room. He has two cameras & a large supply of chemicals belonging to the mission; [Julia] is desirous that they should be made of some avail.’

17 May1862 ‘I have been considerably occupied with photograph[y] the past week. I have been testing the chemicals belonging to Mr. Brown. The old collodion that he brought out with him & that obtained from Capt. [John] Wilson are alike but little avail, but some new collodion that I manufactured works successfully. Mr Brown and Mr Ostrom are both enthusiastically engaged.’[6]

An unpublished manuscript biography of Gulick’s life is held by the Hawaiian Mission Children's Society Library, Honolulu, written by Robert Whitaker in 1936. [7]Referring to the entries above, Whitaker notes:

‘These entries are of interest and importance because it has been claimed for the Rev. S.R. Brown that he was himself the pioneer of photography in Japan, and the teacher of the first Japanese photographer. [8] The facts seem to be that Mr. Brown had taken with him photographic apparatus and materials, and had received besides a gift of such material from a Captain Wilson, but because he had no knowledge of photography himself he had allowed the apparatus to lie unused and the material to spoil on his hands until young Gulick came, and put the apparatus into service, and made up some new and effective materials. Ruth [sic-Julia] Brown, the daughter of Rev. S.R. Brown was evidently eager to have something done at once with the photographic supplies which had lain unused until then, and the enthusiasm of the young woman and the young photographer soon communicated itself to Mr. Brown and his colleague for the time, Mr. Ostrom.’

Gulick’s 1862 journal:

4 June1862 ‘...The Arrival left for San Francisco. All Wednesday I was engaged in printing photographs to send. ... Wednesday night I sat up writing to Mr. Cox, Mr. Shew & Mr. Watkins. I sent a large sized photograph to Mrs. Lacy, another to Mr. Cox & a third to Mr. Benchley. To Mr. Town, Mr. Perkins & Mr. Francis I sent each a stereoscopic view, to Mr. Alden likeness of a Japanese girl, & a Japanese coin. Also to Mr. Douglass, to Mr. Hamilton & to Mr. Fisher & to Mrs. Stiles each a coin. To Mrs. Pierson I sent a likeness of the Japanese girl.... I am this week resting from my photographic labors & am giving more attention to the Japanese Language.’

15 June1862 ‘Mr Brown and Mr Ostrom, who arrived recently from Amoy, have spent several days this week in the fields taking photographic plates while I stayed at home fixing the chemicals and printing photographs from the plates. The most interesting views have been taken at Bokinji [Bugenji, Kanagawa], a large temple or rather a cluster of temples and houses, the residences of the priests, which are shaded by noble trees. Yesterday morning I took my horse & went out to help them on for an hour or so. They returned in the evening, very tired but rejoicing in their success.’

27 June1862 ‘...Mr. Brown and I have been out on a ride over the Yokohama bluffs. We have selected some points from which good views of the town can be taken. A week or two since Mr. Brown sent to Mr. Pruyn two of our photographs as samples of what we can do. Mr. P. writes that he has given them to the chief of the ambassadors that visited the U.S. and that he has obtained permission for him to come & take pictures in Yeddo [Tokyo].’

Although Gulick’s 1862 journal ended on 7 July, we know from his subsequent writings that he did in fact visit Edo in that month. It seems, however, that Brown did not accompany him on this occasion, although he did on a subsequent visit in October.

‘I brought with me from San Francisco a camera and other photographic material for taking stereopticon pictures; and with this apparatus I succeeded in taking photographs, for which I found sale in Yokohama. Dr. Brown had also a camera with which single photographs of a larger size could be taken and photographic material which was in danger of spoiling, as he was too busy to use it. He therefore suggested that I might have the use of these, on condition that he should have part of the photographs to send to his friends in the States who had sent him the camera & material. Mr Pruyn, who was occupying a hired temple in Yedo [Tokyo] as the United States legation, hearing of my success in taking pictures, obtained from the minister of the Shogun, permission for me to come to Yedo and take pictures. The photographs of streets and temples, and of one high, two-sworded official, that I took in Yedo, in July 1862, were, I think, the first photographs ever taken in Yedo. There was at that time a photographer in Yokohama; but he had not been able to take, or to obtain from others any photographs of scenes in Yedo.[9] Under my teaching a Japanese learned to take photographs; and, when I left Japan in 1863, I passed my camera & photographic material to him; and he became one of the first to spread the knowledge of that kind of picture taking among his countrymen.’ [10]

Fig. 2: John Gulick, 'Secretary of the treasury,' 1862-63, illustrated in Addison Gulick's Evolutionist and Missionary.

Fig. 2: John Gulick, 'Secretary of the treasury,' 1862-63, illustrated in Addison Gulick's Evolutionist and Missionary. Fig. 3: John Gulick, 'A yakunin' 1862-63, illustrated in Addison Gulick's Evolutionist and Missionary. This image was reproduced as a stereoview. See Fig. 13.

Fig. 3: John Gulick, 'A yakunin' 1862-63, illustrated in Addison Gulick's Evolutionist and Missionary. This image was reproduced as a stereoview. See Fig. 13. Fig. 4: John Gulick, 'Japanese street scene; barber and customer,' 1862-63, illustrated in Addison Gulick's Evolutionist and Missionary.

Fig. 4: John Gulick, 'Japanese street scene; barber and customer,' 1862-63, illustrated in Addison Gulick's Evolutionist and Missionary.The reference to his teaching the Japanese photographer will be discussed below. With regard to Gulick’s second photographic visit to Edo, we need to refer to two of Brown’s letters:

25 October 1862 [Kanagawa] ‘....By favour of Mr. Pruyn, I have lately been to Yedo, to photograph scenes there. I spent one whole day in taking views in the royal castle, & in the Taikun’s cemetery, where no one had ever done the same before. Mr. Pruyn also introduced me to the Prime Ministers, at their official residence, in the inner enclosure of the Castle, or Citadel, & we spent some 4 hours there. They, the 2 ministers, & a vice minister, some of the highest dignitaries of the land, had their portraits photographed on this occasion, sitting out of doors in a drizzling rain to do it! (three or four times over). An English photographer [William Saunders] did the work. I was introduced as the Chaplain of the Legation, & had a very pleasant time of it. ...All the governors of Foreign Affairs, of the Mint &c, 11 in number were present, & had their photographs taken.

Such a thing as this, i.e. the Gorojio (Great council of State) allowing an unofficial person from another country to enter the castle, & take their portraits, was never heard of here before, & it was at once a great proof of the good feeling they have towards Mr. Pruyn, & also a breaking of the stiffness of official ice, which must have a good effect. I meant to have given you a full account of this visit to Yedo, but have been so hurried to get these pictures made & mounted, that I must defer it till the next opportunity...’

Brown elaborated in his next letter, which is here abridged as it contains significant repetition of the contents of his previous one:

8 November1862 [Kanagawa] ‘...Gen. Pruyn also obtained permission for Mr. Gulick, Mr. Saunders and myself to photograph scenes in Yedo which 2 years ago the Prussian artists could not point an instrument at, such as the Taikun’s castle & grounds, the walls & moats &c. You will see in the collection of pictures I sent by the hand of Mr. Hyatt some of the results so far as my photographing was concerned. Unfortunately my instrument was only a portrait camera, & hence inferior for such purposes. We also had permission to go into the Taikun’s burial ground at Yedo, called Shiba, & photograph its beautiful and picturesque scenery. ... More than a year ago, I purchased $45 worth of pictures, because I had not learned the art of photography myself, and Dr. Simmons, who was expecting to practice it, had left the mission....I hope the 56 pictures sent by the way of California lately may reach them [the Churches] safely. Hereafter I shall be able to go out occasionally, in this neighbourhood, or at Yedo, and photograph scenes, that will, I trust interest my friends & the friends of the good cause in America. I have now a camera of my own, which works admirably, if I could now and then get a small supply of chemicals from the U. States, I should be glad. Hitherto, by selling a few pictures, Mr. Gulick & myself have replenished our stock and materials of this kind, sending to California for them. But they are much more expensive there than at New York. If some friend would send me a few ounces of Nitrate of Silver, prepared for photographic purposes, I would be happy to return him some photographs of Japan. I go out occasionally as a recreation, & there is no country in the world, I fancy, that more abounds in charming views for the artist.’

The Albany Institute of History & Art has in its collections the private papers of Robert Pruyn, the second Minister sent from the US to Japan. In one of the letters sent from Japan to his wife, Pruyn throws additional light on Gulick and his photography:

Legation of the United States Japan

Kanagawa, January 2 1863

My Dear Wife

I have an opportunity to add a few lines as the Timandra will not leave till 10 o c or perhaps 12 o c tomorrow...

Tomorrow I may find time to add a few lines. Please show Mr Abbott the stereoscopic views I send of the Tycoons Cemetary [sic]. The smaller views were taken by a poor young man son of a Missionary in the Sandwich Islands Mr. Gulick I had the pleasure of getting the Ringleader to bring him here for half price + Mrs. Alden collected the money at San Francisco. I say this in order that if anyone wishes any of them they may send for them. He charges 12/ for them not mounted.

I will send Mr. Olcott a set which I had promised. He has six views of Tycoons Cemetary which completes that set.

Please say to Dr Armsby they have a crab which measures 11 feet from tip to tip of claw. I will try to get one for the colleges. Mr. Gulick now has one of that size...

If a painter like Church should visit Japan he would not only make a future but an enduring reputation. The only difficulty he would meet would be that his landscapes could scarcely be regarded as real. Look at the photographs I send even those in my little enclosure. Are they not picturesque? Compare them with the Gables + roofs + chimneys in Albany or New York. See what lines of beauty – what elegant combinations of tree, roof, monument + pagoda....[11]

Later Life

Gulick stayed in Japan until the 26 October 1863, when he left for Hong Kong on board the Paragon. Unfortunately, he makes no further reference to his photography, other than in his writings made in later life and referred to above. Photography was not destined to play a major part, if any, in his future life. Upon arrival in Hong Kong, he began the courtship of his future wife, Emily de la Cour, a thirty-year-old English missionary. They were married on 3 September,1864.

Gulick had gone to China because he had been appointed as a Congregational minister to North China by the ABCFM. He and Emily sailed for Peking but were shipwrecked and rescued by Chinese pirates. Their second attempt to reach Peking succeeded and they spent seven months studying Chinese in the Imperial City before heading northwest for Kalgan (Zhangjiakou), a border city near the Great Wall. Establishing the mission in Kalgan in 1865 was not without its difficulties, and the Gulicks experienced regular hostility from the local population. Nevertheless, they persevered and their missionary zeal encouraged them to make numerous trips into Mongolia. However by 1871 their health was suffering and they left China on vacation, arriving in London the following year.

Emily, who had suffered miscarriages, rested with her family whilst Gulick enjoyed showing his Hawaiian snail shell collection to the Royal Society. He also conversed with evolutionists such as Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace, and published his first article on the subject in the journal Nature.

Gulick found that his contributions to evolutionary theory were well received. However, the council of the ABCFM was not impressed and felt he was staying away from his post for too long. They issued a public reprimand that devastated Gulick. In 1873, he and Emily made haste to return to Kalgan. But just two years later they again needed to leave for health reasons, and this time travelled to Kobe, Japan, where Gulick’s brother, Orramel, was a missionary.[12] Emily died in childbirth on 17 December 1875, and Gulick decided to stay in Japan and spent six years in Kobe working with Orramel. Gulick made a number of trips to nearby Kyoto, where he lectured on natural selection at Doshisha University, an ABCFM school. He had hoped to receive a professorship there but his theological views were considered too liberal. In Kobe he met Frances Amelia Stevens, a girls' school teacher, and the two were married in Osaka on 31 May 1880.The Gulicks were transferred to Osaka where John taught at a Christian boys' school and in his spare time corresponded with the English scientist, George Romanes, about how to achieve a reconciliation between religion and science. John and Frances retired from missionary service in 1899 and moved to Oberlin, Ohio. There John Gulick published his most important work Evolution, Racial and Habitudinal in 1905. This influential work challenged some of Darwin’s earlier views and was critically well received.Husband and wife then moved to Honolulu, Hawaii, and during the next seventeen years Gulick wrote at least forty-two articles on various religious and scientific subjects. The couple raised two biological children of their own and two Chinese children whom John and Emily had adopted. John Gulick died on 14 April 1923.

John Gulick’s Photographs of Japan

John Gulick was not the first to use a camera in Japan, or even in Yokohama or Edo (Tokyo). Eliphalet Brown Jr. took the earliest known photographs in Japan in 1853. Gulick’s earliest photographic activity in Japan took place at Kanagawa on 2 May 1862 when he successfully experimented with Samuel Brown’s photographic equipment. Various photographers had photographed Japan before that date, so where does Gulick’s significance lie in the history of photography in that country?

His photography work in Edo in July 1862 is certainly early. At this time, the American Minister and his staff were the only foreigners residing in the capital. Access was by invitation only, and when Minister Pruyn obtained the relevant permission for Gulick to visit the Legation with his camera, the would-be missionary was following in the footsteps of a very select number of predecessors indeed. Recent research has shown that at this time there was some experimental photographic activity in Edo carried out by Japanese, with at least one commercial studio in operation. We can be fairly certain that up until the time of Gulick’s visit only a handful of foreign photographers had been there. Currently, we only know about the work of William Jocelyn (1858), Pierre Rossier (1859), Captain John Wilson and other members of the Prussian Mission (1860-1) and Charles Dupin (1861).

Gulick was in Edo again in October 1862. This time he was with two other photographers –Samuel Brown and the English professional, William Saunders. Some photographs from this visit have survived, but separating out the work of these three photographers is not easy.

Saunders’ work from this period has proven extremely difficult to locate. The John Hillelson collection contains a group of approximately twelve images from his 1862 visit to Japan, but these have yet to be studied. Also from this series, the Clark Worswick collection contains a view of the Zempukuji Temple at Edo, which housed the American Legation, and an image in Yokohama titled: ‘Bridge with Japanese Guard.’ Nagasaki University Library has a Saunders’ two-plate (of five) panorama of Yokohama. These last three images are illustrated in the writer’s Photography in Japan (2006, pp.98-101). A list of Saunders’ photographs taken in Edo first appeared in the 26 October 1862 issue of the Japan Herald and a transcription appears in the writer’s Old Japanese Photographs: Collectors’ Guide (2006, pp.57-9). The report mentions that Saunders’ prints measured 8 x 10 inches (20 x 25.5cm approx.). It also refers to a selection of stereoviews taken at Edo. Did Saunders really go to the trouble of taking with him both a large-plate and stereo camera? It is at least possible that the stereo photographs Saunders offered for sale after returning to Yokohama were the work of Gulick. The two may well have arrived at some commercial agreement.

During the October 1862 visit to Edo, Samuel Brown took with him a portrait camera, although according to his letters most of the images he took appear to have been scenic. The Pruyn Papers at the Albany Institute of History & Art contain ten street scenes of Edo, each measuring 10 x 8.5cm. Pruyn certainly refers to having Brown’s work in his collection, and the writer is tentatively attributing these ten photographs to Samuel Brown.[13] Of the other two candidates, Gulick used a stereo camera and Saunders used a large-plate camera and, possibly, a stereo camera. In addition, none of the Saunders’ images in the Hillelson, Worswick or Nagasaki collections corresponds to those at Albany.

Fig. 5: Attributed to Samuel Brown, 'Avenue in the Tycoons Cemetary (Sheba), Yedo' October 1862, albumen-print, 10 x 8.5cm approx. Source: Private Papers of Robert Hewson Pruyn, Albany Institute of History & Art. Taken from the same angle as Fig. 4. Note the photographer shown in the background in the act of taking a photograph.

Fig. 5: Attributed to Samuel Brown, 'Avenue in the Tycoons Cemetary (Sheba), Yedo' October 1862, albumen-print, 10 x 8.5cm approx. Source: Private Papers of Robert Hewson Pruyn, Albany Institute of History & Art. Taken from the same angle as Fig. 4. Note the photographer shown in the background in the act of taking a photograph.The Worswick collection contains eight unmounted stereoviews of Edo scenes, and the writer is tentatively attributing these to John Gulick. However, we cannot rule out William Saunders’ authorship in view of the Japan Herald article, and although we would expect any Saunders’ stereoviews to be studio-mounted, more research is required before a positive attribution to Gulick can be made. The only other candidate, Captain John Wilson, can probably be discounted. Although he did use a stereo camera, he left Japan in January 1862, almost four months before Pruyn’s arrival. Furthermore, unlike Gulick, Brown and Saunders, no reference to Wilson is made in Pruyn’s letters. Finally, included among the eight stereoviews are scenes which appear to be taken in the cemetery at Shiba’s Zojoji Temple, where several of the Tokugawa shoguns are buried. Brown refers to photographing this area with his portrait camera in October 1862 ‘...where no one had ever done the same before.’ Brown knew Wilson and if the latter had photographed the Zojoji, he would surely not have made this comment. John Gulick, with his stereo camera, does therefore seem the likely author of Worswick's unmounted stereoviews.[14]

Fig. 6: John Gulick or William Saunders, ‘Akabani Bridge, Yedo,’ 1862, albumen-print stereoview, Clark Worswick Collection.

Fig. 6: John Gulick or William Saunders, ‘Akabani Bridge, Yedo,’ 1862, albumen-print stereoview, Clark Worswick Collection. Fig. 7. John Gulick or William Saunders, ‘View of Street leading to the Temple of Zojoji,’ Yedo,’ 1862, albumen-print stereoview, Clark Worswick Collection. Note the crowd gathered in the distance, perhaps surrounding a photographer. View taken from the same angle as Fig. 2.

Fig. 7. John Gulick or William Saunders, ‘View of Street leading to the Temple of Zojoji,’ Yedo,’ 1862, albumen-print stereoview, Clark Worswick Collection. Note the crowd gathered in the distance, perhaps surrounding a photographer. View taken from the same angle as Fig. 2. Fig. 8: John Gulick or William Saunders, ‘View of the Grounds of the Temple of Zojo,’ 1862, albumen-print stereoview, Clark Worswick Collection.

Fig. 8: John Gulick or William Saunders, ‘View of the Grounds of the Temple of Zojo,’ 1862, albumen-print stereoview, Clark Worswick Collection.On a point of detail, Erika Sanger of the Albany Institute has noted that one of these stereoviews is, apart from the difference in format and a slight shift of camera angle, almost identical to one of the ten images in the Albany collection. The Worswick images are also slightly smaller. One of the Albany images shows another photographer using his camera in the distance. This in itself is indicative of at least two photographers working together.

The writer recently came across a series of what appears to be 1862-3 Gulick stereoviews. The 1932 biography of Gulick written by his son, Addison, contains three illustrated Japanese photographs of Gulick’s. One of these is duplicated in a circa 1870 series of stereoviews published by the Weil New York studio. They are mounted on orange-card stock, each 8.6 x 17.7cm, and appear, from the subject matter, to have been reproduced from earlier negatives or prints. The mount imprints state: ‘P.F.Weil –New York’ and either ‘Stereoscopic Studies,’ ‘Stereoscopic Gems’ or ‘Views of Japan.’ It is not known how many views are required to complete the series; however, five were illustrated on page 68 of the Old Japan Catalogue 34 (2007) and the writer has seen six other examples in the Rob Oechsle collection. There are no printed position numbers or captions, but hand-written titles appear on the back of each mount. It is probable that Gulick was the author of all of the views from this series. Nothing much is known about Weil. A check of the 1870 US Federal Census shows him living in New York with his wife and three-year-old son. Weil’s occupation is listed as photographer, his birthplace is shown as Bremen, Germany and he was then aged thirty-seven. Any relationship with Gulick is unknown.

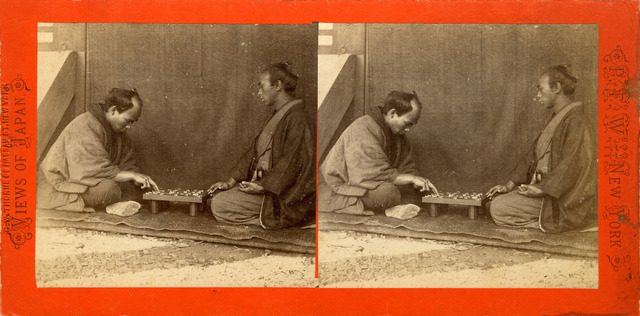

Fig .9: Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Playing Chess,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. Author’s Collection.

Fig .9: Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Playing Chess,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. Author’s Collection. Fig. 10: Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Monument of High Priest,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. Author’s Collection.

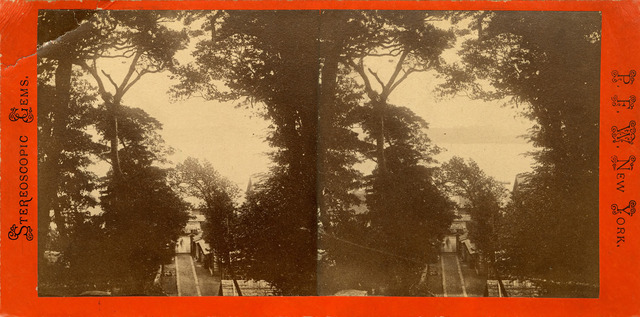

Fig. 10: Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Monument of High Priest,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. Author’s Collection. Fig.11. Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Bay of Yokohama,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. This stereo shows the view from the Hongakuji Temple, Kanagawa, the home of the American Consulate. Author’s Collection.

Fig.11. Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Bay of Yokohama,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. This stereo shows the view from the Hongakuji Temple, Kanagawa, the home of the American Consulate. Author’s Collection. Fig.12. Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Peasantry Girls,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. Author’s Collection.

Fig.12. Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Peasantry Girls,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. Author’s Collection. Fig.13. Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Two sworded Officer Japan,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. Author’s Collection.

Fig.13. Attributed to John Gulick, ‘Two sworded Officer Japan,’ albumen-print stereoview published by the P.F. Weil studio in c.1870 and reproduced from an earlier 1862-63 negative or print. Author’s Collection.Influence on other photographers

It is clear from the above letters and journal entries that Gulick was a more than competent photographer who had mastered the technical complexities of wet-plate photography. His scientific training presumably extended to an understanding of chemistry, since he appeared to have little trouble in testing Brown’s collodion supplies and, indeed, manufacturing replacements. Clearly Brown had not had the time, or perhaps the ability to ensure his chemicals were in working order, and it seems that he had not successfully practiced photography prior to Gulick’s arrival. Gulick’s technical expertise soon changed this, and by mid-May 1862 Brown, and his missionary friend Alvin Ostrom, were enthusiastically producing photographs. In Brown’s letter of the 25 October 1862, he acknowledges that he had only recently taught himself the art, mostly by reading photography books, and that Gulick had assisted him.

It is likely, therefore, that Brown’s oldest daughter, Julia, who at some time became a competent amateur photographer herself, had also not completely mastered the art by the time that Gulick arrived –this despite her friendship with the American businessman Francis Hall who, as an amateur, had been successfully taking photographs in Kanagawa since May 1860. Samuel Brown was friendly with Hall and also knew the professional photographer, John Wilson, from whom he obtained some collodion when the latter left Japan in January 1862. Had Brown been determined to practice photography earlier it seems that he could easily have obtained the necessary assistance. All of this is of interest when we consider that both Western and Japanese sources talk of Japan’s best-known photographer, Shimooka Renjo, learning his trade from either Brown or his daughter Julia.[15]

John Gulick and Shimooka Renjo

Shimooka Renjo (1823–1914) was for many years thought to be the first professional Japanese photographer. However, current research shows that Ukai Gyokusen (1807–87) opened his studio in Edo in 1860 or 1861. Shimooka, nevertheless, was the first Japanese to open a commercial studio in Yokohama, perhaps as early as February 1862 – two months prior to Gulick’s arrival. In the writer’s Photography in Japan (2006) the following notes appeared: ‘...This is independently confirmed by a travel notebook compiled by a visiting American missionary Thomas C. Pitkin: “The arrival of a photographer caused no slight excitement in Yokohama. The result of his efforts appears in many beautiful views of the country including some of the finest in Yedo, which are for sale in London and perhaps also in New York. He left his instrument and chemicals behind which an enterprising native whose gallery I visited was endeavouring to use with no very good success.”’ Pitkin stayed in Japan from approximately November 1861 to February 1862. We know that he was still in Japan during the month of February and that he was back in the United States by August 1862.[16] Pitkin is undoubtedly referring to Captain John Wilson and Shimooka Renjo. If Pitkin is referring to Shimooka’s photographic gallery, then clearly Shimooka was operating a commercial studio from February 1862 at the latest. However, it is possible that Shimooka, a competent artist, was running his own art gallery and was perhaps some weeks or months away from being able to operate a photographic studio.

Considerable uncertainty remains concerning the details of Shimooka’s life, and how and when he came to learn the techniques of photography. Photo-historian Saito Takio quotes a number of admittedly contradictory sources in his article referred to above. There does seem to be consensus, however, regarding Shimooka’s encounter with the American photographer, Wilson. When John Wilson left Japan at the beginning of January 1862, he passed his stereo camera and some photographic equipment and chemicals to Shimooka and apparently instructed him on their use. In exchange, Shimooka gave Wilson a giant painted panoramic scroll, for which the latter thought he could obtain a high price in Europe or America.[17] Shimooka later complained, however, that Wilson’s teaching was not satisfactory. The language barrier would also not have helped. Shimooka seems to have been seeking photographic help and assistance from a number of foreigners in Yokohama. He was friendly with Samuel and Julia Brown, as well as the American merchant Raphael Schoyer and his artist wife. It is very likely that he would have known Gulick, and more than possible that he was still struggling to master the techniques of photography when Gulick first arrived in April 1862. The question is, did Gulick instruct Shimooka in photography?

Gulick and Shimooka knew, and socialized with, the same circle of American friends. All Western and Japanese sources agree that Shimooka was struggling to master photography during 1862-3 period. His commercial success would not come until 1865. There is no record of any Japanese, later to become an influential photographer, who learned the art in Yokohama or Kanagawa in 1862-3. None, that is, except Shimooka Renjo. It is true that there is no conclusive evidence that Gulick taught Shimooka, or even that they met. However, the circumstantial evidence is considerable.

Final Thoughts

When John Wilson left Japan in January 1862, Shimooka had not succeeded in mastering photography. This article has provided evidence that neither Samuel Brown, nor probably his daughter Julia, was in a position to teach photography to Shimooka Renjo before May 1862. Indeed, it may be worth noting that at this time Julia was approximately five months’ pregnant. Saito Takio in his 1997 article refers to one early Japanese source reporting that Shimooka was helped by a female missionary girl named ‘Rauda.’ Presumably this is ‘Lowder’ and although Julia did not become Mrs. Lowder until August 1862, this may be of little consequence. It may well be that the full extent of Julia’s assistance was to effect an introduction to Wilson or Gulick, or perhaps both. More research is needed on this point.

By the time Gulick arrived in Japan in April 1862, Samuel Brown had been under self-imposed pressure to learn photography. Despite being friends with at least two photographers, John Wilson and Frank Hall, he had failed to do so. According to Gulick this was simply because Brown did not have the time. Gulick’s arrival would change that. Living under the same roof, it is not surprising that Brown took advantage of Gulick’s presence and finally mastered the subject.

Gulick mentions that in July 1862 there was a photographer in Yokohama, presumably foreign, who had failed to gain access to, or obtain photographs from Edo. He does not name the photographer who appears to be unrecorded. Charles Parker and Felix Beato did not arrive until 1863. It is possible he is referring to the American Orrin Freeman who opened a studio in Yokohama in 1860. However, he was thought to have ceased photography later that year - or possibly in 1861. The identity of this photographer is therefore something of a mystery.

It is quite likely that Gulick enabled Shimooka Renjo to master photography. However, further research is required before this can be asserted with confidence. Gulick used his own stereo camera throughout his eighteen months’ sojourn in Japan. If Shimooka was the recipient of this camera in 1863, then we should look for examples of stereoviews in his work of this period.

After leaving Japan, Gulick did not seem to retain any lasting interest in photography, at least as a practitioner. Ever practical, he had used photography as a temporary means of making a living. Having secured a missionary post in China, he may have no longer felt the need to continue. Aside from concentrating on his nascent missionary career and enjoying married life, his other great passion of science would ensure that any spare moments would be fully occupied.

Tracking down examples of Gulick’s 1862-3 photography will not be easy. We have the three confirmed photographs illustrated in Addison Gulick’s biography of his father. Apart from those, there is the series of stereoviews published by the Weil studio. Finally, there is the writer’s tentative attribution of the eight stereoviews in the Clark Worswick collection.

Curiously, the short photographic career of John Thomas Gulick seems to throw up more questions than answers. It is to be hoped that some of those answers will emerge in the coming years. In the meantime, Gulick deserves recognition as having played a part in the early development of photography in Japan.

Acknowledgments

This article would not have been possible without the generous assistance of Lynn Ann Davis (University of Hawaii), Anita Manning (independent researcher, Hawaii), Cliff Putney (Bentley College, Massachusetts),Erika Sanger (Albany Institute of History & Art), Professor Takahashi Shinichi (Keio University), Clark Worswick (writer & photo historian) and the staff of the Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library.

Terry Bennett is the author of nine books on early photography in China, Japan and Korea, most recently The History of Photography in China, Western Photographers, 1861–1879, which is reviewed elsewhere in this issue of the TAP Review.

Notes

This extract is taken from the collection of Brown’s letters, held by the New Brunswick Theological Seminary, New Jersey that Brown sent from Japan 1859-1880. Facsimiles are held by the Meiji Gakuin Daigaku, Tokyo. I am grateful to Professor Shinichi Takahashi for providing me with extracts.

At some stage Julia Maria Brown (1840-1919), eldest daughter of Rev. Samuel Brown, became an amateur photographer. By 1862 (and perhaps as early as 1860) she seems to have taken some interest in the subject – see the writer’s Photography in Japan (2006, p.56). Despite the Japanese source mentioned in Saito Takio (1997) it now seems doubtful that she played a significant part in teaching photography to Shimooka Renjo.

Reverend Alvin Ostrom of San Luis, Opispo, California, who entered missionary service in Amoy in 1858 and was there until 1864.

Dr. Duane B. Simmons (c.1832-89). American medical missionary who arrived in Japan with Samuel Brown in November 1859. He was presumably an amateur photographer since he was in charge of the photography equipment taken to Japan. He had a photographic room constructed in his temple in Kanagawa and this was being used by May 1860 at the latest by his friend and American merchant, Francis Hall (1822-1902). However, it does not seem that Simmons himself took an active interest, and Hall may well have been using his own camera and chemicals. For more on Simmons and Hall, see the writer’s Photography in Japan (1853-1912, pp.54 & 57 respectively). See also Notehelfer, F.G. (ed.) Japan through American Eyes: The Journal of Francis Hall (1992).

Captain John Wilson (c.1816-?) was an American commercial photographer who took early photographs in Edo in 1860 after being hired in Yokohama by the Prussian Embassy to Japan. He left Japan in January 1862 having sold his photo equipment to Shimooka Renjo.

Whitaker, Robert. A Freeman of the Frontier (1936, pp.204-5).

See: Griffis, William Elliot. A Maker of the New Orient, (1902, p.179).

Undated manuscript How I reached Japan and my Experiences there Before 1880, held by the Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library.

Private Papers of Robert Hewson Pruyn, Albany Institute of History & Art, CH 532 Box 2 F 14, Item 3.

Orramel Hinckley Gulick (1830-1923) worked in Japan from 1871 to 1893. In Photography in Japan (2006, p.125), the writer confused Orramel with his brother, John. There is no direct evidence that Orramel was an amateur photographer.

In a letter to his wife dated 14 October 1863, Pruyn refers to a visit to the Yokohama studio of Felix Beato. In the same letter he mentions having photographs taken by Saunders and Brown: ‘When I closed yesterday I was under the necessity of returning visit of Bishop Brune of Shanghai and fulfill an engagement with an excellent photographer. I propose sending you a new view of my face not from any vain desire of repetition but because the last attempt was regarded as so much of failure as even to provoke mirth. I have reason to believe that the present effort will be highly successful as we have the artist who was in the Crimea in the employ of the British Gov’t. I have ordered from him some magnificent views of India, China and Japan, which I will send via Cal when they arrive...let Charles Benthuysen prepare three albums one for each of the countries....There will be sufficient for three vols. In the Japan views will be some taken by Mr. Saunders, Mr. Brown which had better be placed in the same Japan volume or perhaps there will be sufficient for two vols.’

For Wilson’s Japan images, see the writer’s Old Japanese Photographs (2006, pp.82-4) and Old Japan Catalogue 34 (August 2007, pp.58-62).

New York Passenger Lists 1820-1957, National Archives: Microfilm Serial: M237; Microfilm Roll: M237_222; Line: 11; List Number: 836A. Pitkin was still in Japan in the middle of February, since Samuel Brown wrote to the Rev. Peltz on 26th February 1862: ‘...I was at Yedo about ten days ago, with the Rev. Dr. Pitkin, Rector of St. Peter’s Ch. Albany.’ For the Pitkin reference, see: Pitkin, Thomas C., manuscript papers, Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Pitkin, folder 2, fragment 14.

For details of this scroll and John Wilson’s career in particular, see the writer’s History of Photography in China: Western Photographers 1861-1879 (2010, pp.199-200); Dobson, Sebastian. ‘Jon Wiruson –arata-na-shiryō kara kaimyō sareta kare to nakama no shashinka tachi’ (2007).

From: How I reached Japan and my Experiences there Before 1880.

Bibliography

Bennett, Terry. History of Photography in China: Western Photographers 1861-1879, London: Quaritch, 2010.

Bennett, Terry. Old Japanese Photographs Collectors’ Data Guide, London: Quaritch, 2006.

Bennett, Terry. Photography in Japan 1853-1912, Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 2006.

Dobson, Sebastian. ‘Jon Wiruson –arata-na-shiryō kara kaimyō sareta kare to nakama no shashinka tachi’, in Nihon shashin geijutsu gakkaishi 16:1 (June 2007), pp.5-20.

Griffis, William Elliot. A Maker of the New Orient, New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1902

Gulick, Addison. Evolutionist and Missionary: John Thomas Gulick. Chicago:University of Chicago Press, 1932.

Gulick, John T. Evolution, Racial and Habitudinal. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institute, 1905. Gulick Manuscripts:The Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library, Honolulu, Hawaii holds a number of largely undated miscellaneous notes, journals and manuscripts relating to John Gulick. These include: 1862 Journal; In the East and the West (c.1906); How I reached Japan and my Experiences there Before 1880; Outline of My Life (c.1912).

Hammersmith, Jack L. Spoilsmen in a “Flowery Fairyland” The Development of the U.S. Legation in Japan, 1859-1906, Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1998.

Ion, Hamish. American Missionaries, Christian Oyatoi, and Japan, 1859-73, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009.

Notehelfer, F.G. (ed.) Japan through American Eyes: The Journal of Francis Hall, Kanagawa and Yokohama 1859-1866, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Old Japan Catalogue 34, Commemorating 150 Years of Japanese Photography (August 2007).

Saitoh Takio. ‘Shimooka Renjo (1823-1914),’ in The Advent of Photography in Japan, exhibition catalogue, Tokyo: Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 1997, pp.173-7.

Whitaker, Robert. A Freeman of the Frontier. The Story of a Modern Ministry. An Account of the Life of DR. John T. Gulick, Missionary, Scientist, and Sociologist, Honolulu: Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library, (1936).