Chaotic Harmony: Contemporary Korean Photography [exhibition catalog]

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Karen Sinsheimer, Anne Wilkes Tucker, and Bohnchang Koo, Chaotic Harmony: Contemporary Korean Photography [exhibition catalog] (New Haven: Dist. by Yale University Press, 2009) 160 pp. ISBN 978-0300157536

Published in conjunction with a survey exhibition of contemporary Korean photography shown at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Oct. 2009-Jan. 3, 2010), and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (May 2010-August 21, 2010), Chaotic Harmony: Contemporary Korean Photography offers an overview of the history of Korean photography along with the writers’ perspectives on the current socio-political issues within Korea as reflected in the works of the forty photographers represented in this exhibition. The two principal essays in this catalogue were written by the show’s organizers, Anne Wilkes Tucker (curator of photography at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston) and Karen Sinsheimer (curator of photography at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art). Both institutions are known for paying particular attention to Asian Art. Bohnchang Koo, whose work is included in the exhibition, provided the essay “Chronology: A History of Korean Contemporary Photography.” Natalie Zelt compiled the artists’ biographies.

The boom in Korean photography is fairly recent, largely because its development was impeded by the Japanese occupation of Korea (1910-45), which suppressed cultural and artistic expressions of Korean identity, and by the devastation of the Korean War (1950-53) that soon followed. In “Past/Present: Coexisting Realities,” Anne Wilkes Tucker explains the dearth of Korean photography during the early twentieth century and describes the major developments during the postwar period. Postwar Korean photographers produced straight photography rooted in realistic journalism, a style further encouraged by The Family of Man, the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark photographic celebration of humanity, which was shown in Korea in April 1957. The subjective photography movement, which swept Japan in the 1950s, did not reach Korea until the late 1960s, and “new color” photographs were not introduced until the 1980s, a decade later than elsewhere. Tucker chronicles the establishment of educational programs in photography and notes that rapid industrialization and greater access to information outside the country allowed Koreans to learn about art movements in other countries, particularly through the homeward return of Koreans who had studied in New York, London, Germany, and Japan. Yet although the development of photography within Korea was impeded for the reasons stated above, it had its own internal development. Once Korean photographers were informed about art movements in other countries, they used their creative resources to produce works such as those that we see here in this show and catalog.

The exhibition is organized into six topics, and each author takes up three of them in her essay. Tucker covers Landscapes, Urbanization and Globalization, and Anxiety, while Sinsheimer treats Korean Cultural Identity and Individual Identity, Memory, and Family.

The “Landscapes” section includes photographs connected to the Spiritualist tradition. Deeply rooted in Buddhism and Shamanism, this tradition is beautifully expressed in Bae Bien-U’s

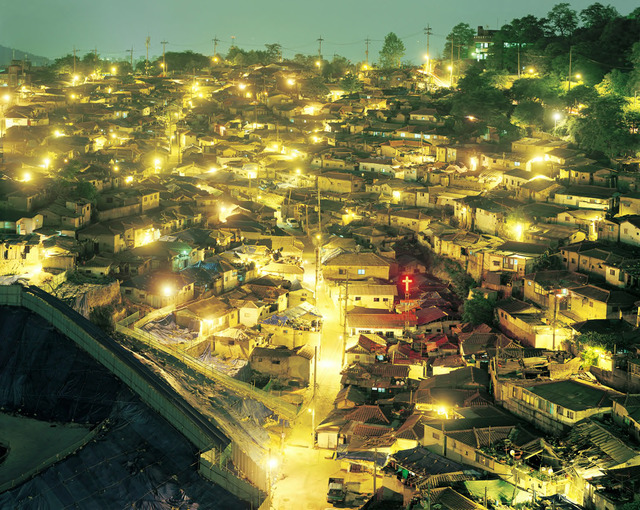

photographs of pine trees planted on sacred sites–the Sonamu series –symbolizing “justice, beauty, and transcendence” as well as in panoramic photographs of dolmens (massive Bronze Age monuments scattered throughout the country amidst peoples’ ordinary surroundings) by Kim Yong-Sung; and in the series Conflict and Reaction (1990-2001) by Lee Gap-Chul, which concentrates attention on the empty spaces of landscape while pushing conventionally important elements such as a statue or person out of focus or out of frame. While capturing Spiritualism in nature may be seen in black and white works by the older generation, younger photographers also attended to the cycle of life, as in Yeorrock’s ambiguous conceptual color photograph registering the fading outlines of cremated cats and dogs.Tucker introduces a wide range of works that show the dramatic transformation of Korea from a traditionally agricultural society to a fast-paced urban one, a process that inevitably brought with it widespread anxiety. Half the photographers in this show were born in the 1970s, and their experiences are chiefly urban. Ahn Sekwon’s

triptych from his series Seoul New Town (2003-2007) depicts the gradual demise of a shantytown in the poor district, Weolgok-dong. The artist visited the neighborhood over three consecutive years as it was demolished piecemeal to make way for modern development. Area.Park portrays urban teenagers amidst standardized high-rise apartment building in the series, Boys in the City, and a pessimistic tone emerges in his Suicide of a Corporate Executive (2004).With travel becoming easier, Korean photographers have widened their scope, embracing globalization and the hybridization of cultures in Korea. Examples include Han Sungpil’s ironic photograph of a replica of the Statue of Liberty standing outside a castle-like love hotel (a hotel for illicit love affairs), and Pa-Ya’s

Noblesse Children #12 (2008), a manipulated image of a doll-like child surrounded by Louis Vuitton accessories.In the section devoted to “Anxiety,” two sub-themes are discussed. First is the alienation experienced by Asians living in the West, as depicted in works like Pak-hyun-doo’s Goodbye Stranger 1, no. 27 (2002). Second is the anxiety of living near an impenetrable yet intriguing North Korea as expressed in the hazy Bordering North Korea, #2 (2005), shot from the Chinese border by Jung Lee.

Tucker’s survey of contemporary Korean photography is a good place to start if one requires a quick introduction to the field, although the essay would have benefited from contextualized reference to the early history of Korean photography from its inception in the late 19th century. She cites at least two projects by each photographer she writes about, which is helpful in giving the reader a broader view of each artist. Of course, space limitations prevent the inclusion of illustrations for all of Tucker’s examples, requiring the interested reader to consult additional materials.

Karen Sinsheimer’s “Identity, Family, Memory: Who Am We?” owes its ungrammatical title to a work by Do Ho Suh that questions the interchangeable “I” and “we” in Confucian society. The essay delves into Korean identity, drawing on sources in Asian studies, sociology, and psychology. Her tautly written essay tackles complex cultural issues, including the demise of the “hermit kingdom” model due to globalization and the diminishment of such traditional values as duty, obligation, and filial piety.

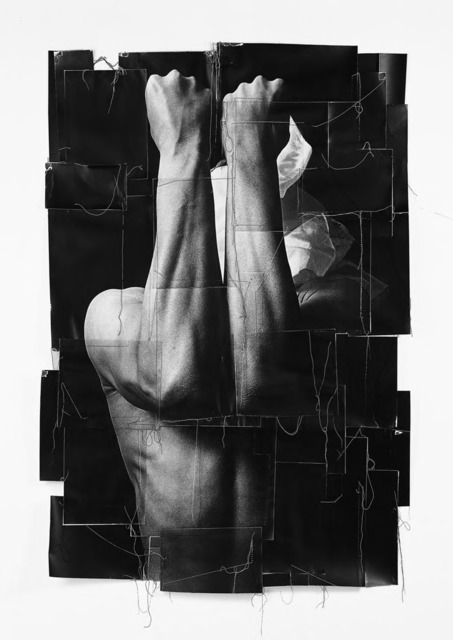

Upon his return from Germany in 1985, Bohnchang Koo,

In the Beginning, I, 1991. gelatin silver print with thread on paper, 53 x 37 1/2 inches (135 x 95 cm)© Bohnchang Koo

In the Beginning, I, 1991. gelatin silver print with thread on paper, 53 x 37 1/2 inches (135 x 95 cm)© Bohnchang Koo EW 03, 2006 from the series Vessel (2004-7) chromogenic photograph of a vessel from Ewha Womans University Museum, 24 1/2 x 19 1/2 inches (62.5 x 50 cm)© Bohnchang Koo

EW 03, 2006 from the series Vessel (2004-7) chromogenic photograph of a vessel from Ewha Womans University Museum, 24 1/2 x 19 1/2 inches (62.5 x 50 cm)© Bohnchang KooSome of the more striking examples discussed in Sinsheimer’s essay address sexuality of youth, both heterosexual and homosexual (e.g., Hyo Jin In’s

series High School Lovers), unthinkable a few decades ago. Hein-kuhn Oh’s series Girl’s Act shows teenage girls challenging the conformity of tradition by exploring fashion and behavior clearly influenced by mass-media popular culture. Layers of cultures co-exist in Korea; some photographers record juxtapositions, while others construct images to represent the country’s hybrid reality. Shin Eunkyung’s Wedding Hall (2002-5) depicts a wedding facility decorated excessively in a Korean interpretation of Western elegance. In Chan-Hyo Bae’s Existing in Costume 1 (2006), the artist dons an elaborate Queen Elizabeth I costume, evincing a clash of genders and mixture of cultural identities.Not all examples are as heavy-handed. In the “Memory” section, Sun Kuhn Oh’s work from his series The Text Book (2006) shows individual figures wearing oversized puppet masks while reenacting childhood dreams, fears, embarrassments, and desires easily understood by Korean viewers.

In “Family,” the last section of her essay, Sinsheimer addresses the traditional and changing structures of the Korean family: inter-racial marriage, Confucian traditions, the nuclear family, and the effects of consumerism on the younger generation. Sunmin Lee’s

photograph of an ancestral ritual, Lee, Sunja’s House #1 – Ancestral Rites (2004), represents the loosening of Confucian practice as the participants wear Western dress. Yet modernization goes only so far, since the women do not take part in this vestige of patriarchal society.A pair of photographs from Jeong Mee Yoon’s

The Pink & Blue Project (2005-8), created during her studies in New York, shows portraits of children surrounded by their accumulated belongings arranged neatly on the floor. All pink for girls and all blue for boys, the massed items, suggest that a global consumerist culture, rather than national or ethnic values, determine male and female versions of identity and acquisition. As the author observes, these images of children engulfed by material abundance are “a portrait of consumerism.”Although Sinsheimer’s critical interpretations are generally apt, her comparison of Kyungwoo Chun’s images with those of Julia Margaret Cameron, Kim Oksun, and August Sander are not as fitting or as convincing as one might hope.

Bohnchang Koo’s “Chronology: A History of Korean Contemporary Photography” covers 1962 to 2008, and provides titles and dates of significant exhibitions, and information on photography societies and clubs, photography magazines, and photography programs at colleges and universities. A pioneer in disseminating Korean photography within his own country, Koo provides a schematic account that will be useful for scholars pursuing their own research, despite the fact that it concentrates heavily on recent events that are known to the author.

Overall, the catalog and the exhibition are welcome contributions to the study of Korean photography, a field in which a paucity of material in English inhibits critical discourse. One advantage of having two outsiders mount this project is that they were apparently free from the traditional, rather cliquish selection process usually employed in Korea. Relying on countless interviews and first-hand portfolio reviews, Sinsheimer and Tucker took a fresh look at the field, identifying distinctive works they also consider representative. Just flipping through the catalogue, one notices a diversity of images not confined to names known only abroad, and many mid-career photographers and new names appear. By giving attention to Korean artists not well known to Western audiences, both the exhibition and the catalogue challenge our stereotypes about Korean photography and offer an up-to-date summary of photography in Korea. However, by focusing principally on photographers based in Korea, curators omit such prominent figures as Nikki S. Lee, known for her experimental projects addressing identity and masquerade. Also notably missing are works with an overtly political content or of a vulgar nature. Nonetheless, the collection is valuable for both aesthetics and subject matter. The respectful, almost academic compilation maintains a coolness that is neither passionately optimistic nor dreadfully pessimistic. By and large, this carefully edited volume gives us a view of the world of Korean photography as seen through highly- trained eyes and insightful minds.

Reviewed by Hyewon Yi, Director of the Amelie A. Wallace Gallery at SUNY College at Old Westbury, New York. Currently Yi is writing a doctoral dissertation on contemporary photography at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.