Why Asian Photography?

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

For the first issue of the Trans-Asia Photography Review, we asked thirteen key thinkers to respond to a set of fundamental questions. These individuals – scholars and artists from Australia, China, England, India, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan and the U.S. - have all been actively engaged with issues of photography and culture in their own work. The questions we asked them were:

- What are the most important factors shaping contemporary photography in the region of Asia you know best? What were the most important factors encouraging the development of photography in this region historically?

- Under what circumstances is national or cultural context important to understanding a photograph? When is it not important? How can photographs made within one cultural context be best understood by viewers from another culture?

- Is a trans-national history of photography (including photographic work from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas) desirable or imaginable? If so, how might you imagine it?

- What further questions should be asked regarding photography and culture generally, and photography in Asia specifically?

The respondents were invited to answer one or more of these questions, or to write a more free-form commentary on “photography and culture”. Their responses, taken together, make it clear that this is a loaded and challenging topic. These authors write about the critical importance of taking culture into account, and also about the difficulties of doing so without falling into a number of serious ideological traps. They point to the historic complexities of relations between Asian and Western nations as well as among cultural groups within Asia and the Asian diaspora. They suggest new models and topics for future research. They question the notion of “Asian photography” in important ways.

As you read these wide-ranging and substantive responses, you may be moved to add your own thoughts. If so, please send them to the Editor at [email protected], along with a brief bio of yourself.

—Sandra Matthews

Contributing Authors:

- Geoffrey BATCHEN

- Patrick FLORES

- IIZAWA Kotaro

- KOO Bohnchang

- Anthony LEE

- Young June LEE

- Sheila PINKEL

- Christopher PINNEY

- Aveek SEN

- Karen STRASSLER

- Laura WEXLER

- WU Hung

- WU Jiabao

Geoffrey Batchen

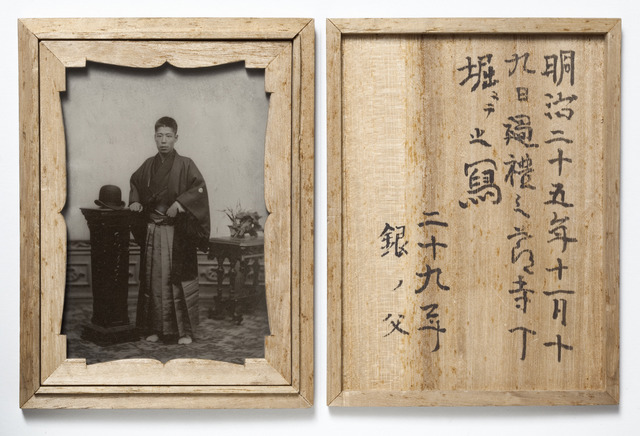

Makers unknown (Japan), Standing man with bowler hat on a pedestal, November 19, 1892. Ambrotype in kiri wood case, with inscribed calligraphy in ink, 12.4 x 9.5 x 1.5 cm (closed). Collection of Geoffrey Batchen, New York. Reproduction: Cathy Carver

Makers unknown (Japan), Standing man with bowler hat on a pedestal, November 19, 1892. Ambrotype in kiri wood case, with inscribed calligraphy in ink, 12.4 x 9.5 x 1.5 cm (closed). Collection of Geoffrey Batchen, New York. Reproduction: Cathy Carver1. What are the most important factors shaping contemporary photography in the region of Asia you know best? What were the most important factors encouraging the development of photography in this region historically?

The relationship of inside and outside, of the local culture to that of the West, has always been the primary factor mediating the production of photography in Asia. As an Australian living in New York, my knowledge of that relationship is relatively slight (unless you count Australia as part of Asia). However I’ve always been interested in those photographic practices that speak to that tension between inside and outside. Examples might include pictures made for tourists by the Japanese photographer Kusakabe Kimbei, involving the elaborate depiction in his studio of a set of stereotypes invented to suit the interests of both Meiji nationalism and Western orientalism, or Japanese ambrotypes made at about the same time which show their subjects in traditional dress standing next to a bowler hat on a pedestal. A closer analysis of these kinds of pictures might offer a way to articulate the political and cultural complexities being negotiated by photographers in this period. But so would an examination of the photography associated with Provoke magazine in the 1960s, informed as it is by the influence of William Klein, on the one hand, and local Japanese urban planning developments, on the other. But these are all obvious examples. The more difficult challenge would be trace this tension in work that shows no obvious sign of it, whose meanings are opaque to me, or worse, are seemingly transparent to my gaze.

2. Under what circumstances is national or cultural context important to understanding a photograph? When is it not important? How can photographs made within one cultural context be best understood by viewers from another culture?

Context is important in all circumstances. Of course, a photograph can be understood without any knowledge of the context in which it was produced (everyone has some understanding of the images of Seydou Keïta, despite most observers’ profound ignorance of Malian culture in the 1940s). However that understanding will be necessarily limited and circumscribed. Photography has the disturbing capacity to cross cultural boundaries and appear to speak a global language. But this ease of dissemination is deceptive. A snapshot made in China does not necessarily mean the same as one made in New York, even when they look identical. As far as photography from Asia is concerned, outsiders should do their best to become acquainted with appropriate local contexts even while constantly reminding themselves of the impossibility of attaining such knowledge. In short, humility and caution should be our permanent companions.

3. Is a trans-national history of photography (including photographic work from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas) desirable or imaginable? If so, how might you imagine it?

I think such a history is necessary, even if it will always be imperfect. Histories of photography that don’t offer a global perspective are no longer acceptable. Of course, the problem is deciding exactly what a ‘global perspective’ consists of. The recent rash of regional, national histories (Danish photography, Dutch photography, Australian photography, Russian photography, British photography, and so on) suggests that dissatisfaction with the old Amero-Eurocentric account is widespread. But what to put in its place? If I had to imagine an alternative, I would begin from a set theme—memory, for example—and then explore the many different ways this is induced in photographic practices around the globe, and even within one’s own culture. Sameness and difference would thus become the organizing principals of my history. One advantage of such an approach is that it can abandon questions of originality and innovation, as well as chronology and comprehensiveness. It will merely aim to be representative. Work from elsewhere, from outside one’s own cultural boundaries, can be included within such a scheme, as long as the caution already mentioned is kept in mind and is appropriately conveyed to the reader. However this global approach is dependent on the availability of informative regional histories, and one thing we are sadly lacking at the moment are such histories for many Asian countries, written by indigenous scholars but available in English. Until this situation is improved all efforts at a global or trans-national history will be severely handicapped.

4. What further questions should be asked regarding photography and culture generally, and photography in Asia specifically?

The questions to be asked of photography appear to be endless, so imbricated is this medium within every aspect of modern life. As I have already suggested, we badly need more native informants from Asian cultures willing and able to inform outsiders of local histories and debates. For too long these cultures have been spoken for by others, or simply remained inaccessible to Western scholars. On the other hand, there is of course a politics at stake in all speech and all knowledge and we need to be acutely attuned to this politics here. ‘Asia’ is the name of a great challenge for photographic scholarship. How we deal with it will determine the future of our discipline, as it will the future of the world’s political and economic infrastructure.

Geoffrey Batchen is Professor of Art History at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand. He is the author of Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (1997), Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History (2001), and Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance (2004). Batchen has recently edited Photography Degree Zero: Reflecting on Roland Barthes' Camera Lucida (2009), and Suspending Time: Life, Photography, Death (Japan: Izu PhotoMuseum, 2010).

Patrick FLORES

Untitled (Turquoise Room #4). 48’’ x 60’’ Lightjet Photograph. 2007. Edition of 3 + 2AP. © Gina Osterloh. Courtesy of the Artist, Silverlens Gallery(Manila) and Francois Ghebaly gallery (Los Angeles)

Untitled (Turquoise Room #4). 48’’ x 60’’ Lightjet Photograph. 2007. Edition of 3 + 2AP. © Gina Osterloh. Courtesy of the Artist, Silverlens Gallery(Manila) and Francois Ghebaly gallery (Los Angeles)  Blind Rash (Shooting Blanks). 30’’ x 38’’. Lightjet Photograph. 2008. Edition of 4 + 2AP. © Gina Osterloh. Courtesy of the Artist, Silverlens Gallery(Manila) and Francois Ghebaly gallery (Los Angeles)

Blind Rash (Shooting Blanks). 30’’ x 38’’. Lightjet Photograph. 2008. Edition of 4 + 2AP. © Gina Osterloh. Courtesy of the Artist, Silverlens Gallery(Manila) and Francois Ghebaly gallery (Los Angeles)Alighting

How do we resist photography in a time immersed in image? With much difficulty certainly, because of its sheer immediacy and compelling wonder, capturing an authentic, everyday anecdote or an alluring, otherwordly effect.

And so, how do we go against its grain? To permeate the picture with context, so that photography could not exist without that which is against, besides, and beyond it? Or might it be productive to let the experience of photography provisionally prosper in a personal sphere, away from the simulations of a highly mediatized world, within a zone of contact like a museum, an institution that evokes history in the present and through a subject that sees through?

These are questions that I pondered as I organized a photography exhibition in Manila in 2008, a tangent to the Japanese counterpart titled Counter- Photography. If the latter is interested in probing the medium’s tendency to document, the Philippine exhibition is keen on the politics of this tendency in the context of contemporary photography in the country and to some extent in Southeast Asia. In Thailand, for instance, the King in the nineteenth century decided to breach taboo and let his image be reproduced in photography, which was like stealing the spirit. In Indonesia, a photographer named Cephas worked for the Sultan of Yogyakarta and took images of custom and place, from the wayang performances to the magnificent Borobodur.

The archival tableau of an imposing Dean C. Worcester standing next to a seemingly importuned Philippine native is emblematic of this predicament: a census taker, culture translator, and museum maker had required the photograph to record the ethnic woman, measure her in light of his stature, regard her as a type, and infer character from the pose.

The history of photography in the Philippines is marked by this form of revelation: making something known, staging the apparent so that consciousness could be heightened, conquering the fear of invisibility. Undoubtedly, such scrutiny can either ravage the subject, reducing her to a thing of tradition, or entitle her presence as she transfigures into what the National Hero Jose Rizal would call a double vision, an enchantment of affinities, in his uncanny Spanish: “el demonio de las comparaciones.” Comparisons, indeed, bedevil, bewitch.

Photography, therefore, in a post-colonial situation questions the condition through which it has gained recognition as a medium: how its capacity to reveal is at once the technique to conceal and how its attempt to give a truthful depiction of everyday life is in the same vein a desire to play out a fantasy of the self and the other, the photographer and the photographed. It is, therefore, at once radically empirical and irreducibly allegorical: so present, so foretelling.

Here, the duality between appearance and absence does not hold; it gives way to a kind of disclosure, an inclination outward, a history of image and photography that is an opening. The exhibition “Swarm in the Aperture”: Recent Photography in the Philippines discerns the depth of this crevice, this slit in time that light apprehends. The title is taken from Eric Baus’s poem “She Said I Was Tired of Living Like a Sieve in a House Between Atmospheres” that enigmatically speaks of a quotidian sublime. It ends with the line: “What I'm asking for is a fish border, a fence equal to her scattered breath.” The multitude at the fringes of the frame finally hovers.

Gathered in this modest project are eleven photographers who have in various ways invested talent and temperament in the discipline, whose practice is distinct from contemporary installations that appropriate photography, or photo media, and from exclusively commercial pursuits that mistake the picturesque for the beautiful. Exhibitions of photography in the Philippines come few and far between, and there seems to be little room in the art world for artists to explore the range of this form with both rigor and whimsy. It is tempting to confine the tendencies in these expressions within such convenient categories as conceptual or photojournalistic, experimental or social realist, ethnographic or formalist. But we would rather offer a wide latitude and prompt everyone to engage the photographs with intimacy, and take away from this process of creative cherishing nothing less than a critical memory of “image” as a postcolonial condition: coveted as appearance, obscured as truth, disclosed as reality, document of dignity, evidence of inequity.

Patrick Flores is Curator of the Vargas Museum, Adjunct Curator of the National Art Gallery, Singapore,and Professor of Art History, University of the Philippines. He is the author of Painting History: Revisions in Philippine Colonial Art(1998).

IIZAWA Kotaro

1. What are the most important factors shaping contemporary photography in the region of Asia you know best? What were the most important factors encouraging the development of photography in this region historically?

The economic development of Japan in the post-war period. As the camera and film industry developed in Japan, photography rapidly became more accessible to the greater public. With the new accessibility of cameras, interest in photography developed among young people as a means of self-expression. At the same time, economic development gave rise to a variety of social contradictions and anxiety. Photography became a main avenue of expression, and a means of solving these various issues.

2. Under what circumstances is national or cultural context important to understanding a photograph? When is it not important? How can photographs made within one cultural context be best understood by viewers from another culture?

I think it is very important to have the context when understanding a photograph. If you have an image that was taken within your country, your environment, or your culture, on a surface level it's easy to understand. But still, if you really want a deeper understanding and reading of an image, you need a much more specific cultural context as well as the reasons why the object represented in the photograph is there, why a specific individual is being represented this way, etc.

3. Is a trans-national history of photography (including photographic work form Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas) desirable or imaginable? If so, how might you imagine it?

If you think about photography within the larger framework of people and images, of course a trans-national history of photography is possible and desirable. But in examining the “macro-history” of a given country or culture, it is also important to contrast this with the “micro-history.”

4. What further questions should be asked regarding photography and culture generally, and photography in Asia specifically?

We shouldn't talk about broad issues so much. Instead, we should focus on more specific concrete themes. For example, how photographers in Asia deal with and represent themes of “body,” “landscape” “labor,” “food,” or “life and death.”

Iizawa Kotaro has written numerous books on the history of Japanese photography, and coedited the 41-volume seriesNihon no Shashinka. He founded the magazine Déjà-vu in 1990 and was its editor in chief until 1994. He is active internationally as a curator, critic and historian of photography.

Translation of Mr. Iizawa’s responses by Benjamin Turk.

KOO Bohnchang

1. What are the most important factors shaping contemporary photography in the region of Asia you know best? What were the most important factors encouraging the development of photography in this region historically?

Numerous factors shape contemporary photography in Asia. Photography in each nation has developed at its own speed. One apparent factor is the global system of interconnected computer networks and the development of technology. Photography in both China and Korea depicts a shifting culture, in particular rapid urbanization and the effects of industrialization on society. The market for contemporary Asian photography has been prompted especially by Chinese artists, as economic reforms begun in the 1980s have turned the People’s Republic into an emerging superpower. Internationally the art market has enlarged and globalized, and that is another factor that stimulates Asian photography.

2. Under what circumstances is national or cultural context important to understanding a photograph? When is it not important? How can photographs made within one cultural context be best understood by viewers from another culture?

Emerging from a repressive regime, in which every attempt was made to obliterate the country’s culture, the expression of these reclaimed cultural values became a dominant feature of Korean photography.

Photography took an anthropological approach to rediscover these values. Understanding the culture in each nation is important to understanding the context of its photography.

3. Is a trans-national history of photography (including photographic work from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas) desirable or imaginable? If so, how might you imagine it?

Yes, a trans-national history of photography is desirable. Photography reflects the conditions of each country. One concern about being so connected by the internet and exchanging information by rapid technology is that it directs international trends. Artists can have easy access to, and become too familiar with current trends in contemporary art and the art market.

4. What further questions should be asked regarding photography and culture generally, and photography in Asia specifically?

We can’t deny this new era of art capitalism dominates the art scenes in Asia now and every place else. In recent years obvious changes have taken place in the structure of contemporary art. The rise of art events such as shows, biennales, and auctions, brought the wave of contemporary art fever to its climax. The rapid rise of contemporary photography in Asia has been affected by art markets, which conventionally draw most attention to a few artists who have been shown repeatedly. Art markets and critics should make an effort to take a look at unseen photography in Asia.

Koo Bohnchang is a photographic artist and curator whose work has been exhibited in Asia, Europe and the U.S. As a curator, he has worked to bring international exposure to contemporary Korean photography (for example, curating the first major show of Korean photography in the U.S at the Fotofest Biennial in 2000) and to bring together the work of photographers within East Asia, (such as in exhibitions he curated for the Daegu Photo Bienniale 2008).

Anthony W. LEE

I happened to be in Seoul recently and came across an exhibition, at the Museum of Photography, of the work of Joo Myung-Duck. Now seventy years old, Joo has had a long and distinguished career photographing the uneven changes in post-war Korean culture and society. The exhibition was two-fold, the larger and more celebrated part devoted to a new series on roses, the smaller devoted to his earlier street work. Reminiscent of some of Tina Modotti’s photos, the new pictures pay loving attention to petals and folds and also, like Modotti’s, to dog eared and overripe edges (Fig. 1). Alternating between high metaphor and fleshy sensuality, the subject is not one for which Joo has been associated, and it seems a new and exciting venture—reviving him, discomforting him, forcing him into a different appreciation of his camera and lens. He has described the project as something that would challenge him for years to come. “From here onward,” he wrote for the exhibition brochure, “I have to do even better work.” If in early 2009 the journal Korea Focus could proclaim that “photography was not considered an art in Korea just three or four years ago” but that “the situation has changed and photography is being increasingly recognized as an art form,” from that perspective Joo’s turn to roses could be understood as evidence not only of a transformed, revitalized sensibility but also of a new openness to art photography among a wider South Korean audience. Printed very large (much larger than most of his previous work) and in catchy metallic and sepia tones, the photographs have been garnering lots of attention.

But it was the second and smaller part of the exhibition, devoted to some of Joo’s very early street scenes, which, though escaping critical notice, especially caught my eye. During the 1960s when he was still a working photojournalist, Joo walked the streets of Incheon, the port city just west of Seoul, and took pictures of that city’s Chinatown. At the time, Incheon’s Chinatown was a very poor quarter in a very poor city. Once a vibrant, bustling neighborhood, with more than 10,000 Chinese residents and a lively trade with China, by the late 1960s Chinatown was a ghetto, with few Chinese and even fewer of the old import shops and restaurants. A combination of several factors—the Communist Chinese economy gone sour, a zealous exclusionist policy toward immigrant Chinese adopted by the South Korean government, and the generally awful social conditions in the post-war era—had conspired to turn Incheon’s Chinatown, at one time the only place in all of South Korea worthy of the name, into a dead zone. Something about Joo’s photos captured the depressing state of affairs (Fig. 2). In the spare streets, with hardly a hint of sociality, with few signs of material or cultural life, the photographs are desolate, dreary, and forlorn. Something vital has been forsaken in Chinatown, and any hopefulness that it might be restored has been lost too.

This is about as much historically informed meaning I could give to the photographs, and it’s almost certainly incorrect. I wondered how these photographs were understood when they were first published. South Korea, after all, was then struggling mightily with its own versions of deprivation, foreign occupation, isolationism, and loss. What bonds of affinity or understanding or, conversely, what specific forms of nationalist feeling and ethnic difference did Joo tap into? What imagination of cultural difference did he encourage or allow? (Of the same Chinatown and its few inhabitants, for example, the short story writer Oh Jung Hee has one of her young protagonists explain, “they [the Chinese] were yeast of our infinite imagination and curiosity. Smugglers, opium addicts, coolies who squirreled away gold inside every panel of their ragged quilted clothing, mounted bandits who swept over the frozen earth to the beat of their horses’ hoofs, barbarians who sliced up the raw liver of a slaughtered enemy and ate it according to rank, outcaste butchers who made wonton out of human flesh, people whose turds had frozen upright on the northern Manchurian plain before they could pull up their pants—this was how we thought of them.”)

Over the years, I have seen many photographs of many American Chinatowns, but I cannot remember seeing any, as a sustained vision of a place, that are quite like Joo’s. The closest that come to mind—in their simplicity, sparseness, unobtrusiveness, and sense of loss—is a series by the 19th century San Francisco photographers H. W. Bradley and William Rulofson. But there are huge differences. While Joo’s Chinatown is on its downward spiral, Bradley’s and Rulofson’s is about to take off. In the 1860s and 1870s when the partners were their most prolific with the camera, San Francisco’s Chinatown was booming, with tens of thousands of residents, immigrants and migrants moving back and forth to the busy docks, shops and restaurants (and brothels and gambling rooms) doing non-stop business. The sense of stillness and emptiness in their pictures was mostly the by-product of the slow, big-plate cameras they were using; and the sense of loss, real or imagined, was related not to any depressing experience imputed to the Chinese but to that of others, who had designs on the very neighborhood that the Chinese had made their own.

As I ponder how to answer the questions posed by Trans-Asia Photography Review, Joo’s photographs continually come to mind. The Chinatown pictures seem especially poignant and in need of better understanding than I can give, as they are now being used to narrate a shift in Joo’s career, from street scenes to flowers, from journalism to art; and as Incheon’s Chinatown is today undergoing a revival. (In a bald-faced effort to attract Chinese investors, Incheon has manufactured a brand new Chinatown. “Can you build a Chinatown without Chinese?” a correspondent for the New York Times asked.)

I have no clear answers, only questions, prompted by the photographs. What we need—what I need—are more precise terms to understand them, the sorts of terms about national and cultural contexts and trans-national histories (and, I’d add, comparative practices) that TAP is generally proposing. These things matter, always. Or else we end up, in the case of Joo’s pictures, with the kinds of clunky, inexact, and only blandly useful claims.

Anthony Lee is Professor and Chair of Art History at Mount Holyoke College. He is the founder and editor of the series Defining Moments in American Photography, published by the University of California Press. His most recent book is A Shoemaker's Story: Being Chiefly about French Canadian Immigrants, Enterprising Photographers, Rascal Yankees and Chinese Cobblers in a Nineteenth-Century Factory Town (2008).

Young June LEE

1. What are the most important factors shaping contemporary photography in the region of Asia you know best? What were the most important factors encouraging the development of photography in this region historically?

My description of this matter is limited to my experience within Korea, which may differ from what can be found in other parts of Asia. The most prominent factor shaping contemporary photographic culture in Korea is technology. We are talking about the ramifications of technology in two different directions. The first direction is the changing technology of photography. Needless to say, one can easily think of digital technology. However, unlike what most people think, the progress of digital technology in photography is not limited to producing pictures of a better quality. Korea is the nation which boasts the world's best internet network. Almost all the PCs in Korea are networked to each other and one can find internet cafes (called “PC rooms” in Korea) even in the remotest country village. Therefore, the meaning of digital technology does not lie in the quality of the picture (as represented by the number of pixels in a given camera model), but in the speed with which information is transmitted through a network. I want to call the current status of photographic culture in Korea the “regime of speed”. Indeed, speed is a very basic parameter when one talks about the capacity of a computer. Everything else is secondary compared to the influence that this speed exerts on our life. Since 1888 when Kodak began to advertise its wizardry with the famous phrase "You press the button, we do the rest," photography began to fly. It prevails over other forms of information. But the shortcoming of the civilization of speed is that it can't spare time for reflection. Photographs are wired without any consideration of their meanings.

It seems that the current speed culture in photography will be culminating in consumer technology. This trend has already been demonstrated by Apple's launching of iPhone and iPad (iPhone was introduced to Korean consumers as late as last year, due to Samsung’s tenacious obstruction ). Steve Jobs claims that the future information technology will focus on the consumer side, not on the hardware provider's side. Needless to say, among the most eye- catching functions of both the iPhone and iPad are the ways they enable consumers to easily make pictures, store them and transmit them anywhere they want. Photography has reached a utopia with the help of technology as represented in smart gadgets. But what does it mean to be a consumer of the image? This question does not seem to entail a positive answer. Rather, we have to worry about the onslaught of the new realm of consumer technology in photography, which will be discussed in the next section.

Before dealing with that problem, I would like to elaborate on another direction of technology related to photography. It is surveillance technology, which has reached the level of another form of self- representation, for one sees oneself as mirrored in the monitor of the surveillance camera network. Until the 1990s, surveillance technology was thought to be an operation of an evil-eyed Big Brother. These days, surveillance technology is one of the means to ascertain the safety of civil life. In the past, surveillance cameras used to belong to a few “watchers”, such as police and government agencies. Right now, surveillance cameras are like many cells found along with the capillary organization. It is uncertain who is watching who. The iPhone's feature that puts one's vision right at the place where the surveillance camera is located on the street is surprising, in that it appropriates the vision of the surveillance camera and brings it back to ordinary individuals.

However, along with this proliferation of smart technologies, one is faced with a certain lack. What characterizes contemporary photography in Asia is abundance. Especially in the digital era, everything photographic is abundant in Korea. Everyone carries a camera, every shop sign carries photographic images, everybody has mobile phones equipped with cameras. New topics and subjects are being discovered, developed and disseminated everyday on the internet for ordinary amateur photographers. However, contrary to this landscape of abundance, what really characterizes the photography scene in Korea is a 'lack'. Photography in Korea is like a monster roaming the globe without knowing where it is going. In that sense, I hesitate to dub it 'culture'. Since “culture” means activities to shape the meanings of life, an activity without an orientation toward where it is going is just a blind practice. So I claim that contemporary photography in Korea is blind. Indeed, photography has been blind all during its history, and it has been a blinding machine as well, all during that time. Beneath the splendid veneer of the spectacles offered by photography, it does not show what kind of cultural, historical, social and practical scaffoldings have been supporting them. So, while it seems to show the truth of the world, photography has been concealing the complex conditions in which this truth is produced. The more photography shows, the more it hides from its visual field. Furthermore, this very fact of concealment is concealed. So we are faced with a double concealment in photography: the concealment of the concealment.

What makes things worse in Korea is the combination of consumerism and photography. Digitization has been playing quite a dialectical role in this case. Digital technology is a blessing as it guarantees a democratization of images far larger than that offered by traditional analog photography. With digitization, more people have access to photography and more things become exposed to its vision. Digital technology is a source of vital energy in every aspect of culture in Korea, and photography is no exception. However, as digitization cannot be imagined without its alliance to consumer culture, this immediately cancels the vitality it has produced and turns it into a blind play of signs. So photography becomes blinder with the onslaught of the digital.

At this juncture, what is decisively lacking in Korea is the intellectual activity to critically understand contemporary photography. This does not mean that every ordinary individual who carries a digital camera should be an intellectual equipped with theoretical knowledge of photography. What is lacking is the conceptual understanding of photography as visual culture. When we think about ordinary people's keen, critical attitudes toward political issues such as President Lee's disastrous plan for ruining the natural environment of Korea by building dams in all the major rivers, their lack of a questioning attitude toward the very photograph that carries their identity in their citizen's ID card is quite amazing.

In sum, the most important factor in contemporary Korean photography is

the complexity of the situation in which material hardware is abundant, but intellectual thinking about what that means is lacking.

2. Under what circumstances is national or cultural context important to understanding a photograph? When is it not important? How can photographs made within one cultural context be best understood by viewers from another culture?

In Korea, researchers are faced with photographic documents from the past which do not carry much information about the contexts in which they were made. Just a conjecture as to the meaning of a photograph can be a dangerous venture as it is embedded in its own specific context, whether it be national, cultural or racial. Unless it is a piece of a fragmentary Surrealist image, a photograph always carries with it specific information. However, this does not mean that a photograph should always be accurately received by foreign viewers. Just as Roland Barthes has written in "the Death of the Author" (1965) that the meaning of a text is the sum of all the responses toward it, so all the understandings and misunderstandings by diverse viewers will be counted as proper responses that illuminate the contour of the meaning of a photograph. A lot of slippage and misunderstanding will occur along the borders of nations and cultures. For example, in 1991, Newsweek printed a photograph of Korean female college students with a caption saying ' slave to money.' This incident brought up issues of racial and sexual prejudice in the American media’s representation of Koreans. Although the incident exasperated many Koreans, it clearly also showed what some Americans thought of as an accurate representation of Korea. So, instead of pursuing the understanding that is best, one should pursue the process in which an understanding is tested.

3. Is a trans-national history of photography (including photographic work from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas) desirable or imaginable? If so, how might you imagine it?

As I am not a historian, my answer to this question is quite limited. However, one can surely say that the history of a certain photograph is always intertwined with that of other nations or cultures. This is more true since Edward Said wrote of the implications of Orientalism. As a culture is always caught in the self-other relationship, the production and dissemination of a representation always entails the problem of how it will be understood by those standing on the other side of the border. Homi Bhabha suggests the notion of ambivalence in postcolonial discourse, in which the colonizer is dependant upon its subordinate, psychically and existentially. Along these lines, a culture produced in one region always hides its mark imprinted in the other region. Identity politics is the name of this concealment. A trans-national history of photography, if there is any, should take the form of demonstrating the structure of concealment.

When one tries to write the history of Korean photography, one can't avoid writing about the history of Japanese photography. By the same token, the history of American photography should written along with reflection on what has been done to the Native Americans. Inevitably, a trans-national history of photography will take the form of dissecting and analyzing complex discourses that form the identity of photography in a certain region.

Yes, a trans-national history of photography is imaginable, but in a form quite complex and conflicting, as it should encompass those aspects , such as historical imagination and the discourses of identity politics, which shape the very notions of 'history' and 'nation'. It will be an effort of convergence that requires the work of historians, critics and thinkers. In Korea, such a convergence is barely beginning to take shape, and it will take a while to see the result.

Young June Lee is a critic and professor at Kaywon School of Art and Design. He is the author of Image Critic-From Hairstyle to Satellite Image (2006), Machine Critic (2007) and Gaze of the Critic-Twenty Thoughts on Photography (2009).

Sheila PINKEL

The Value of Transnational Analysis

Today it is common knowledge that the context in which a photograph is shot and viewed determines how that photograph will be understood. However, in a discussion of transnational photography, exploring how a photograph can be used as a basis for unpacking history can be instructive. The concept of context includes the country, period in history, kind of physical and conceptual space in which the image is seen and the history of the person making the photograph. This dialogue is made more complex when an image is made by a person from one country who then exhibits it in another country. This situation allows for an investigation of how the image has been read and received in both countries.

In order to clarify the complexities of relativistic reading, I am going to discuss an image made by the Vietnamese- American photographer Brian Doan, which caused a firestorm of controversy in Orange County, USA, during January and February of 2009. The image, shot in Vietnam, is a portrait of a young Vietnamese woman wearing a red tank top with a yellow star on it symbolizing the Communist Vietnamese flag, sitting next to a table on which there is a little red book with a cell phone on top and a gold bust of Ho Chi Minh.

At this point, it is important to note that there are two Vietnamese flags. A red flag with a gold star symbolizes the Communist state of Vietnam. A yellow flag with three horizontal red stripes symbolizes the South Vietnamese state that was conquered by the Communist Vietnamese during the Vietnam War which ended in 1975. Thus, the tank top references the state of Vietnam. Vietnamese who were/are allied with South Vietnam and anti-communism use the yellow flag as their symbol of state.

Doan’s photograph was included in two exhibitions in Orange County, California in early 2009. The first was a group exhibition entitled FOB II: Art Speaks in Santa Ana, California at the VAALA (Vietnamese American Arts & Letters Association) Center which included the work of 50 Vietnamese- American artists. Doan's photograph was vandalized on a number of occasions during this exhibition. The glass protecting the image was scratched, a woman protester spat on it, someone sprayed red paint on it and attached a tampon and underwear to it. This exhibition was closed by a public official several days after its opening because of massive protests by local Vietnamese groups. The second show, a solo exhibition by Doan entitled “The Vietnamese” and “Echoes of the Land,” at Cypress College, Orange County, California, opened several weeks later. In this second exhibition the vandalized image was exhibited in a glass case for protection and to reflect the previous controversy. Protests at the opening of this second show resulted in a public dialogue between the protesters and Doan organized by Jerry Burchfield at Cypress College.

To understand the complexities of interpretation of this image we need to understand various perspectives, the anti-communist Vietnamese immigrant community living in the United States, the Vietnamese community currently living in Vietnam, Vietnamese in Vietnam at the time of liberation in 1975, and the perspective of Doan, a refugee who has spent most of his adult life in the United States and who views himself as an artist.

Brian Doan, age 40, was born in Quang Ngai, in central Vietnam and was imprisoned several times for trying to escape from Vietnam. He finally immigrated to the United States when he was 23 years old. He is an associate professor of photography at Long Beach City College. He was surprised that his image elicited this level of upset among the local Vietnamese community. Doan says his photo is a comment on fashion, pop culture and disaffection in contemporary Vietnam.

“Almost all of my work is about the narrative. I create work in many layers, combining history and props to tell a story. I wanted to capture what it is like for the younger Vietnamese generation growing up in Vietnam now. I purchased the t-shirt, had her put her hair up in a ponytail because during communist times, this was how I remember women wearing their hair. I also put a red book on the table with a cell phone on top of it. Some may take it as making fun of how Chairman Mao in China made people carry around a red book with his quotes, but all I'm really commenting on is that the cell phone is now more important than the book. I directed the girl to look away as if she were dreaming.”[1] "She lives in the communist country, but look at her. She's looking away, dreaming. She wants to escape Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh is next to her, but communism is no longer in her. She wants to dream of other things," said Doan. [2]

Tram Le, one of the FOB II show's curators, said she doesn't interpret Doan's work as pro-communist. "Actually, it's a critique of communism," Le said. "These symbols are actually banal objects of tourism. They can be bought, sold and exchanged." [3]

However, in the United States, a T-shirt with the symbol of the current Vietnam state flag is read by some Vietnamese Americans as supporting the oppressive regime of Communist Vietnam. For the immigrant generation displaying a representation of the Communist Vietnamese flag is like showing a Nazi symbol in a Jewish community. The immigrant generation of Vietnamese- Americans fought hard against communism and the Ho regime during the Vietnam War and fled Vietnam to save their lives. For them any representation of the communist Vietnam state, including a red T-shirt with a gold star on it, is read as an endorsement of a political ideology they oppose. The symbol of their allegiance is a yellow flag with three horizontal stripes.

Among those who spoke against Doan's work was his father, Han Vi Doan. During the Vietnam war, Han Vi Doan was a high-ranking government official in central Vietnam, in charge of security before the 1975 fall of Saigon. After the fall of Vietnam, he spent 10 years in a communist re-education camp. He now lives in Huntington Beach, California. Doan heard that his father was critical of his photograph. After the controversy Doan visited his parents during the Lunar New Year but his father refused to see him. He made another visit on Mother’s Day but nobody in his family wanted to talk to him. For Han Vi Doan, Brian’s image represents a pro- communist position which he does not support.

Other incidents reflect this attitude. In 1999, a Vietnamese-American displayed the communist flag and photo of Ho Chi Minh in front of his store, Hitek, in Westminster, California, which resulted in the Hitek Incident when 15,000 people held a candlelight vigil [4]. In 2004, Vietnamese American students at California State University, Fullerton, threatened to walk out of their graduation ceremony demanding that the university replace the current flag of the Vietnam with the flag of South Vietnam [5]. This debate is not restricted to the United States. During World Youth Day 2008 held in Sydney, Australia, tensions flared between the 800 Vietnamese pilgrims who used the officially-sanctioned Communist flag and the 2300 Vietnamese Australian pilgrims who used the South Vietnamese flag, reflecting the complex history of Vietnam and the Vietnamese diaspora [6].

Would this image have been made thirty -five years ago after end of the Vietnam War and if it had, how would it have been received? At that moment in history this image would not have been made. After a thousand years of Chinese domination, eighty years of French domination and twenty years of U.S. domination, the communist Vietnamese were not interested in seeing the symbols of state so cavalierly represented. Wearing the symbol of state on a T-shirt or having a mass produced golden colored replica of the head of state would have been viewed as denigrating the state and the hard fought battle which the people had waged for independence.

However, according to Doan, today this image would not provoke controversy among the youth in Vietnam. Today the tank top representation of the Vietnam flag and the little bust of Ho on the table are common in Vietnamese tourist markets. In Vietnam the commodification of these symbols reflects the growth of capitalism and the disaffection of the youth with the state. Like images of Mao, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley and Che, this image of Ho Chi Minh in its current mass produced state is drained of its ideological cache and has reached the status of icon.

We do not know how this image would have been received in Vietnam had the model worn a yellow tank top with three horizontal red stripes. In the Vietnamese markets such a tank top or flag cannot be found. About his intention, Doan says, "I'm totally not a Communist, like they label me. We went through a lot of hardship under the Communists...I'm not anti-Communist or pro-Communist. I'm just an artist." [7] However, judging from the diverse response of Vietnamese around the world to representations of the two Vietnamese flags, it appears that neutrality is impossible. Doan’s position reflects his own history and training and can be understood as yet another point of view in this evolving history of transnational representation. We would not understand this complexity if we did not undertake this analysis.

Sheila Pinkel is Professor of Photography at Pomona College and an artist who exhibits her work nationally and internationally. She is an international editor of "Leonardo", the journal devoted to the intersection of art, science and technology.

Christopher PINNEY

Must we be forever condemned to study territories rather than networks?

Perhaps it is useful to imagine a spectrum with ‘photography’ at one end and ‘culture’ at the other. What might be called ‘core’ photographic history (by which I mean that which describes Euro-American practices) erases ‘culture’ as a problematic whereas ‘peripheral’ or ‘regional’ histories by virtue of their very regionality tend to foreground ‘cultural’ dimensions of practice. In part this reflects the continuing neo-colonial conditions of global photographic history[1] in which, as Deborah Poole has noted “...the non-European world and its images have been oddly elided [even] from virtually all the photographic histories that attempt to link photography with the history of disciplinary and ideological systems forged during the height of Europe’s colonial era” ( 1997:140). The ‘sovereign’ Euro-American Subject of whom Dipesh Chakrabarty wrote (and who, within conventional historiography, has now been largely displaced) remains – within the history of photography – alive and well. The ex-nomination of the centre endures: British and French photography is just ‘photography’ whereas African or Indian photography is always configured by an unshakeable ‘local’ specificity.

This stress on locality is symptomatic of a ‘territorializing’ logic: photography imported into India, or Japan or Peru, presumed in some sense to be French or English, is co-opted by a new set of Indian, Japanese or Peruvian practices. This is certainly a view that I have previously argued myself (Pinney 1997) so it is worth marking the distance between the argument I am exploring here and that earlier position. A key exemplar of a process of ‘Indianisation’ would be the overpainting of the photographic surface (see Gutman 1982, and Allana and Kumar 2008). Similar narratives have been developed in other locations. Following Shunnojo-Tsunetari’s thwarted 1843 attempt and subsequent success in 1848 in importing a Daguerreotype camera into Nagasaki, Eliphalet Brown takes a daguerreotype camera to Japan as part of Commodore Perry’s 1854 Expedition, and in the same year the first Japanese Daguerreotype manual appears (“Ensei Kikijutsu” – “Use of Novel Devices from the West”) and it is then only a matter of time before photography appears incarnated in a territorialized guise. Thus Kinoshita Naoyuki in his extremely interesting account directs our attention to photography’s co-option as “ihai”, the wooden memorial tablets “on which were written the Buddhist names of the deceased” (Naoyuki 2003:18-19). Similarly, when approaching work by the Peruvian photographer Martin Chambi (or for that matter Figueroa Aznar) our desire is usually to localize: to find in their astonishing portraits and landscapes an embrace of a sophisticated Cusqueno indigenismo, a political romance of territory (Poole 1997:168-197).

We touch here on the paradox of the reaffirmation of an old order that is frequently permitted by the conquest of a new territory, what (in another context) George Orwell described as “the loyalties and superstitions that the intellect had seemingly banished” which “come rushing back under the thinnest of disguises” (2008:124). The same might be said of the concept ‘visual culture’. This quasi-anthropological demotic initially promised a liberating challenge to a civilizational art history still gripped by an exclusionary aesthetics. However, this promise of freedom bore within it what now seems like the return of the repressed. Michael Baxandall’s “period eye” (1972) and Clifford Geertz’s “Art as a Cultural System”(1983) constituted the visual as a new territory for a familiar kind of anthropology in which culture, history, and locality continued to be the ruling concepts

Within the history of photography regionalization is , as I’ve suggested, a mark of centre-periphery asymmetries. But it is also evidence of a more general desire to dissolve technical practice in the balm of heroic human activity. Photography in these accounts is simply, or chiefly, a void, waiting to be filled by pre-existing cultural and historical practice. These stories of photography are like those eighteenth-century object narratives (“The Story of My Pipe” or “Memoirs of an Armchair” etc) described by Roland Barthes which he suggested were in fact not the stories of the objects themselves, but of the hands between which those objects passed (Barthes 1972). These stories of heroic culture and heroic man triumphing over the camera are articulated within a structured choice between what Latour describes as the notion of technology as “neutral tool” and its obverse, technology as “autonomous destiny” a dichotomy that might be rephrased as a choice between “culture” versus “technological determinism” (Latour 1999:178-180).

My suggestion here, following Latour, is that we need a different kind of history of photography, one which allows us to escape from the choice of either a technological determinism, on the one hand, or (on the other) a belief in photography’s neutrality in which what matters are remarkable individual practitioners, or photography’s “Indian-ness’ or ‘Peruvian-ness’, all of which give colour to an otherwise blank space. We need to come up with a new kind of ratio, a new way of conceptualising photography as technical practice itself in a state of continuous transformation (or as Barthes would say “declension”), which is imbricated with equally fluid subjects (both in front of, and behind, the camera) and to understand the ways in which this entangled practice has itself transformed that domain that many of us used to call ‘culture’.

Must we be forever condemned to study territories rather than networks?[2] The Trans of TAP is a good place to start, especially if it blossoms as a space paradigmatic of all networked practices, and rejects the default setting as localized footnote to a general (ie Euro-American) history.

Christopher Pinney is Professor of Anthropology and Visual Culture at University College London. His books include Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs (1997), Photography’s Other Histories (co-edited with Nicolas Peterson, 2003), and The Coming of Photography in India(2008).

References

Allana, Rahaab and Kumar, Pramod (2008) Painted Photographs. Coloured Portraiture in India Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing Ltd.

Barthes, Roland (1972) ‘The metaphor of the eye’, in Critical Essays trans. Richard Howard, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1972, pp. 239-248.

Baxandall, Michael (1972) Painting and Experience in 15th century Italy Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Geertz, Clifford (1983) ‘Art as a cultural system’ in Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretative Anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

Gutman, Judith Mara, (1982) Through Indian Eyes: 19th and early 20th Century Photography from India New York: Oxford University Press & International Center of Photography.

Latour, Bruno (1993) We Have Never Been Modern trans. Catherine Porter, London: Prentice Hall.

Latour, Bruno (1999) Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies Harvard University Press.

Marien, Mary Warner (2006) Photography: a Cultural History. London: Laurence King (2nd edition).

Naoyuki, Kinoshita (2003) ’The early years of Japanese Photography’, in Anne Wilkes Tucker et. al. eds. The History of Japanese Photography New Haven: Yale University Press & Houston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Orwell, George (2008) ‘Inside the whale’ in George Packer comp. All Art is Propaganda: Critical Essays, Orlando: Harcourt Inc.

Pinney, Christopher (1997) Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs London: Reaktion/ Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Poole, Deborah (1997) Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Aveek SEN

Under what circumstances is national or cultural context important to understanding a photograph?

Depends on who is doing the understanding, why and for whom. There is a way of looking at, archiving, understanding and writing about photography that is entirely historical, sociological or anthropological. And here context is all-important. Usually, this kind of writing is academic and specialized; aesthetic criteria are irrelevant or subordinated to the more levelling gaze of the social sciences. The (usually hierarchical) distinctions between art and not-art, or between documentary, popular, commercial, journalistic or art photography, do not apply in such readings. So, if we are, say, studying representations of women, or immigrants, or dwarfs, then we should be looking at every kind of photography from advertisements, police shots and ethnographic records to photo-essays in Granta and the work of Arbus, Salgado or Iturbide, without getting into disputes as to whether what we are looking at is art or not, or if it is art, then whether we are looking at good art or bad art. We are more interested here in content, rather than form, and we are producing critical knowledge using photographs as primary documents. We could have chosen to look at folksongs or newspapers or films, and done the same sort of work with them, without bothering very much about aesthetics (although the aesthetic or formal aspects of these documents could make our interpretations more nuanced and layered).

But the moment we get into questions of a different kind of meaning or affect (that is, once we take photography into art galleries, art auctions and art publishing houses), and raise questions of beauty and form and aesthetic, emotional or intellectual impact, then the role of context, especially national context, becomes far more ambivalent and complicated. A different set of priorities and criteria, together with a different kind of politics, takes over. Someone should write about the Politics of Contextualization, and about how a great deal of academic work is structured by that politics. For instance, why is it that Henri Cartier-Bresson, William Eggleston, the Bechers or Jeff Wall is Photography, whereas Graciela Iturbide is Mexican photography or Dayanita Singh Indian photography? I suspect this is not only political, but also geopolitical, going back to the ancient geographical divides in post-Enlightenment European epistemology: Who looks at whom? Who studies whom? Who writes about whom? Who is the subject, and who the object, of knowledge and interpretation? And the related questions: What do we need to know in order to understand a Western artist? And what do we need to know in order to understand an Asian artist? Who are ‘we’? In the first case, not very much context is required because Western art is assumed to be universal, transcending national or geographic differences. It is Art. But Asian art is not Art, it is Asian art. Therefore, a learned understanding of the various contexts in which it is produced is essential for doing it justice: it must always be tied to its time and place. So, Dayanita Singh cannot depict loss, absence or fear, but must always represent upper-class India or, in her more recent work, the desolation of industrial India. We hardly ever have books, articles, photo-book introductions or catalogue essays explaining what is Belgian, French, Canadian or American about Belgian, French, Canadian or American photography because we are expected to respond to Belgian, French, Canadian or American photographs as we respond to the Venus de Milo or the Mona Lisa, without having to know about Classical Greece or Renaissance Italy. But not so for ‘Asian photography’. An entirely different approach to looking, understanding and knowing has to be constructed, mastered, disseminated and repeatedly invoked for such a category to be taken seriously in the global field of vision. This applies not only to those who are looking at it, showing it, collecting it and writing about it, but also to those who are making it. That is, Asian photographers themselves often end up internalizing this way of seeing and start producing work for it and from within it, presenting their work in books and in shows according to its requirements. They readily accept the ‘contexts’ in which their work is invariably read, and then start perpetuating that reading of their work, together with the assumptions that inform these readings, by actually producing work that can be written about, shown and taught within these prefabricated frames and perspectives. Non-Asia looks at Asia in a certain way, and therefore Asia looks at, and projects itself, like that too. A couple of centuries ago, this was called Colonialism or Imperialism. Then Edward Said called it Orientalism. Now it is called Context, and the right-minded, well-intentioned, academically respectable sound of the word obscures the structures of power/knowledge/funding that create this primacy of Context.

This is why I am profoundly uncomfortable with the notion of Asia (or any other region) as context – especially when that notion is created and sustained in the non-Asian parts of the world, and then globalized.

Three Questions

- Does it matter that Gedney was American?

- Does it matter that Wall is Canadian?

- Are these Asian photographs?

Aveek Sen is the Senior Assistant Editor for The Telegraph, Calcutta, India. He also reviews books, films, classical music, art, and photography, and is the 2010 winner of the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award in Writing. Sen is currently working on a book on the intersections of photography, literature, cinema, and the other visual arts.

Karen STRASSLER

Picturing “Indonesians”

Heri Gunawan, a Chinese Indonesian studio photographer, made this portrait of his sixteen year old daughter in 1998, shortly after student-led demonstrations forced an end to President Suharto’s New Order regime. In the portrait, Laura wears the typical dress of a college student—blue jeans—and her determined expression, headband, and clenched fist against a backdrop of a burning building evoke widely circulating media images of the Indonesian reform movement (reformasi). Laura’s portrait stakes a claim to belonging in the Indonesian nation through identification with a quintessential Indonesian subject, the student activist. It is, clearly, a self-consciously “Indonesian” portrait, but it is not possible to view this image within a strictly national frame.

“As if” national subjects

In picturing Laura “as if” she were an activist, Heri’s portrait calls to mind the dramatic scenes of protest pictured in national and international newspapers, and serves as a kind of surrogate for the souvenir photographs that many students took of themselves at reformasi demonstrations. Yet the portrait’s dramatic lighting, painted backdrop, and carefully arranged and static pose unambiguously place it within the studio portrait genre. Unlike journalistic images and student souvenir photographs that rely on an eyewitness principle, a claim of having been there, the studio portrait deploys a different photographic ideology. It assembles legible signs to form an overtly theatrical image that documents not an actuality but an unrealized potential, not a fact but a desire to participate in a collective historical process. This overt performativity—a tendency to materialize that which is unrealized and to make visibly present that which remains out of reach—is characteristic of the studio portrait genre as it has taken shape within the Indonesian context.

Heri explained, “…this [portrait] was my idea…Laura as a person who wants to demonstrate…I wouldn’t let her take part in the demos, only for the photograph. Actually she wanted to, but I forbid it because of the danger. In her spirit, she wanted to.” Imagining that the photograph gave tangible form to Laura’s desire, Heri nevertheless acknowledged his mediating role, explicitly noting that his photograph documented his “dreams” for Laura rather than—in any direct fashion—her own.

There is considerable irony in Heri’s “dreaming” of Laura as an ideal Indonesian subject. The image takes on more ominous associations when we consider that most of the buildings burned in the riots of 1998 were businesses owned by Chinese Indonesians, and that a number of young ethnic Chinese women were brutally gang-raped during those riots in Jakarta. As a Chinese Indonesian, Heri is painfully aware of his and his daughter’s uncertain belonging within the nation. One might say that it is only in the modality of the “as if” that someone like Laura can occupy the subject position of “Indonesian.”

I would argue, however, that despite indigenist ideologies that posit some Indonesian subjects as more “authentic” (asli) or natural Indonesians than others, the “as if” modality of the studio portrait is essential to its work in the making of national subjects more generally. In this view, Laura’s status as Chinese Indonesian does not render her portrait as an Indonesian qualitatively different from those pribumi(“native”) Indonesians whose belonging in the nation has historically been less problematic; rather it exemplifies and brings to the fore the always performative and necessarily mediated process by which one assumes an Indonesian identity— and the crucial role of photography in this process. Although usually in ways less obvious and self-conscious than in Laura’s portrait, studio portraits have long provided people an opportunity to put themselves into the picture of a specifically Indonesian modernity. As with Laura’s portrait, Chinese Indonesian photographers, often drawing on models from global and other media images, have been key mediators of these processes of visual interpellation.

Chinese Indonesian Photographers and “National” Appearances

Heri had crafted his portrait of Laura for professional as well as personal reasons. Since opening his small studio in the central Javanese city of Yogyakarta in1984, Heri has been creating portraits of his family and himself as a means to experiment with new lighting techniques, poses, and backdrops. These contoh (“example”) images cover the walls of his studio, providing models for his customers. The portrait of Laura as an activist thus not only materializes Herry’s dreams and Laura’s desires for the family album but also models a possible pose available to anyone who enters the studio. In making contoh with his daughter as model, Heri follows in a long line of Chinese Indonesian photographers who fashion new appearances for their customers.

One might say that in Indonesia, despite its associations with colonial power and “Western” modernity, photography nevertheless has a “Chinese” face. Since the late colonial period, and especially after Independence, the majority of photographers in Indonesia have been ethnic Chinese. Oral research with studio photographers and their descendents reveals a consistent pattern of immigrants from Canton who established familial networks of studios across Indonesia and—although more research needs to be done on the pattern’s regional dimensions—throughout Southeast Asia.

In the postcolonial period, Chinese Indonesian photographers served as cosmopolitan cultural brokers who drew on their transnational ties as they helped craft the appearances of modern Indonesian subjects. In the 1950s, for example, they collaborated with Javanese backdrop painters to develop a distinctive iconography of “Indonesian” backdrops—featuring tropical landscapes, modern architecture, and luxurious interiors. These backdrops reinvented colonial-era tropical paradise imageries and reworked global media images of modern affluence. Ironically, despite their status as members of a transnational minority whose belonging in the nation remains precarious, ethnic Chinese photographers have molded—and quite literally modeled—modern Indonesian appearances.

Global Media as Imaginative Resource

Heri’s portrait of Laura places her within a visual iconography of the “student activist” that has an important genealogy within Indonesia. The image of the long-haired activist with headband recalls imagery of earlier student movements and of the pemuda (youth) who fought in the Indonesian revolution (who themselves went to the portrait studio to assume the pose of pejuang (fighters). Nor, of course, is the iconography of student activism only national; students who participated in the movement were acutely aware of the way their images would gain efficacy through their resonance with images of student protest in other parts of the world. As a recognizable visual icon, the student activist is simultaneously national and global.

In the portrait’s ensemble of signs, the backdrop against which Laura immediately evokes the banks and stores burned during reformasi riots. But in fact its history is more sedimented. In fashioning Laura’s portrait, Heri actually recycled a backdrop he had made years earlier, when he was inspired by scenes from the 1974 Steve McQueen film Towering Inferno. When he pictured Laura as a student protester, he recalled the Towering Inferno backdrop: “I imagined Reformasi...Solo is burning, Jakarta is burning...and then I remembered...this background.” Heri explained that he often designs studio sets inspired by films and television shows from the United States and Hong Kong, whose images sear his memory but leave no material trace. As he put it, “I have many leftover memories that I want to be able to see, to own.” Realizing them in the studio’s theater-space, he brings otherwise ephemeral and distant images into tangible presence. Culled from the flow of media images, such signs become detachable elements of a visual repertoire, available for recombination and use in ways that may or may not retain the associations of their ‘original’ sources.

Laura’s portrait offers an obvious example of the way that “global” media may be put to use in the fashioning of self-consciously “national” appearances. Heri’s recycling of filmic images in this and other backdrops he has used in his studio brings to mind the comment of an elderly Javanese woman I interviewed about the experience of going to have one’s portrait made in the 1950s. Recalling how studio employees would unfurl colorful backdrop after backdrop, allowing customers to choose among them, she commented, “It was just like the movies!” If global media provide imaginative resources for people’s acts of self-fashioning, studio portraiture is one medium for making those resources available. Studio photographers work to translate these ephemeral, circulating signs into accessible and locally relevant idioms, making the distantly glimpsed appropriable as accoutrements of the self.

Toward a Transnational History of Photography?

This brief examination of Heri’s portrait of “Laura as a student activist” offers some suggestions for how we might think about the question of “Indonesian photography,” and perhaps “Southeast Asian” photography more generally. I have suggested that we cannot understand photography in this region without addressing its mediation by ethnic Chinese photographers. Acknowledging the role of ethnic Chinese photographers means abandoning a set of tired dichotomies that too often structure the stories we tell about photography. No longer can we posit photography as a “Western” technology imported into an “indigenous” context; nor can we assume photography’s history in Indonesia to be an example of the “global” encountering, and either colonizing or being indigenized by, “the local.” The pivotal role of Chinese photographers as cosmopolitan cultural brokers also requires us to abandon a way of thinking that posits the “transnational” as opposed to the “national,” instead demonstrating the ways that transnational flows of technology, imagery, capital, and people have been integral to the very project of nation-making. Rather than ask what makes photography “Indonesian,” or “Asian” for that matter, we might more profitably ask how photography participates in the making of “Indonesia” and in the mediation of other imagined social entities and identities.

Karen Strassler is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Queens College – CUNY. Her book, Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Postcolonial Java, has recently been published by Duke University Press.

References Cited:

Bertecivich, George C. Photo Backdrops: The George C. Berticevich Collection. (Exhibition Catalogue), San Francisco: Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, 1998.

Frederick, William H. 1997. “The Appearance of Revolution: Cloth, Uniform, and the Pemuda Style in East Java, 1945-1949,” in Outward Appearances: Dressing State and Society in Indonesia. Henk Schulte Nordholt, ed. Leiden: KITLV Press, pp. 199-248.

Liu, Gretchen. 1995. From the Family Album: Portraits from the Lee Brothers Studio, Singapore 1910-1925. Singapore: Landmark Books.

Laura WEXLER

Chinese Family Photographs and American Collective Memory

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), many Chinese families destroyed personal objects that could identify them to marauding Red Guards as class enemies. As Li Songtang, founder of the Songtangzhi Museum of salvaged architectural remnants in Beijing recently explained to The New York Times, “People were so afraid that the Red Guards would find antiques in their home, they would toss them in the river at night so no one would see.” (1/19/09). They burned their own books and smashed their own heirlooms. Among these casualties were family photographs. Photograph albums were dangerous possessions because of who and what they portrayed. Intimate relationships, treasured objects, milestones of achievement, mementos of travel, domestic spaces – all the kinds of images that in the U. S. are usually reasons to cherish family albums were at that time the reasons to obliterate them. Americans often say that if catastrophe strikes the first thing they will try to save is their collection of family photographs. For many Chinese during the Cultural Revolution, to save the family’s photographs would have been to precipitate destruction.

Plenty of family photograph albums did survive, however, both in China and overseas. These albums have seldom been thought worthy of collection and study, but they are invaluable archives of social history and of personal and collective memory. I am hoping that collections of these albums will grow, here and in China, and that interest in these albums will also increase if people can feel comfortable sharing the family history behind the images. Some collections have begun. I myself made a small collection during the half-year I lived in Beijing in 2008. I have also visited the small collection at the International Center of Photography in New York City. There is room for much, much more scholarship in this exciting new endeavor.

However, it will be important to understand the subtleties of cross-cultural interpretation as this research goes forward. There could be no starker example than the Chinese experience to show that the meaning of domestic photography is dependent upon its context. But the general (some might say naïve) faith many Americans maintain in the therapeutic value of commemoration underestimates the trauma and elides the potential ongoing terror of the attempt to hold on to certain memories through photographs.

The visual field is not an innocent field; it is thoroughly imbued with relations of power. As Americans learn to trans-nationalize the history of photography by studying its global histories and practices, and as domestic images from elsewhere come to inhabit our imaginations, visual theorists will need to confront photography’s political agency in this expanded field as well. China’s experience with family photographs offers new paradigms for future work.

Laura Wexler is Professor of American Studies, Professor of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Yale University, and Co-chair of the Women Faculty Forum at Yale. She is the author of Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of U.S. Imperialism (2000), Pregnant Pictures (2000, with Sandra Matthews), and numerous essays on photography and American visual culture.

WU Hung

1. What are the most important factors shaping contemporary photography in the region of Asia you know best? What were the most important factors encouraging the development of photography in this region historically?

To answer these two questions we need to consider the notion of “Chinese photography” more carefully and critically. Historically speaking, early photographs by Felice Beato, Milton Miller, and John Thomson—-to name just a few——were “photographs OF China” made by foreign photographers for a Western audience. These works were rarely distributed and reproduced in China at the time; and some of them reflect a strong colonialist mentality. But can we say that the appearance of Chinese studios and independent Chinese photographers marked the beginning of “Chinese photography”? The answer is by no means clear, because early Chinese studios and photographers in Hong Kong or Shanghai basically adopted Western practices and styles. It is problematic to define “Chinese photography” purely based on the ethnic identity of the photographer.

A similar situation exists in contemporary Chinese photography. First, how do we define a work as a “contemporary” Chinese photograph”? Can we call present-day photojournalism contemporary photography? Or are only those following current international artistic trends, such as conceptualism and appropriation, “contemporary”? Again, the answer cannot be found purely in style or mode. Local history, globalization, etc. are all important factors to consider.

Chinese photography is a large field and encompasses many different genres, subjects, purposes, and styles (e. g. ethnographic, medical, journalistic, portrait, architectural, artistic, propagandistic, commercial, etc.). Each genre and subject has its own historical conditions, representational conventions, and sociopolitical context. It would be too simplistic to ignore their specific conditions and contexts.

2. Under what circumstances is national or cultural context important to understanding a photograph? When is it not important? How can photographs made within one cultural context be best understood by viewers from another culture?