On Evidential Strategies in Manchu

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

This paper deals with the category of evidentiality, which is one of the most important linguistic concepts in general, and the means of its expression in the Manchu language. Despite the fact that our paper is the first to explore this area in Manjuristics, we have made several important observations and have come to a number of interesting conclusions. In particular, we found that semantico-grammatical complexes consisting of information and perception verbs, followed by the suffix of conditional converb, are mostly used to code evidential meanings. In addition, certain analytical syntactic constructions are also in use, but they are less frequent. Thus, both factors, lexical and grammatical, contribute to encoding evidential meanings in Manchu, and these complexes and constructions can be considered as a basis for the formation of the grammatical category of evidentiality as such. Our results shed some light on how this category originated and developed crosslinguistically.

论满语中的言据性策略

Liliya M. Gorelova

俄国科学院与奥克兰大学

Arthur Chen 陈辰

山东大学

“言据性”是语言学中最重要的范畴之一,本文将围绕这一概念展开讨论,并探讨言据性在满语语文中的表现形式。尽管是满学研究界中涉足该领域的初次尝试,本文仍然提出几项重要的发现和若干有意思的结论。我们特别发现,由信息和感官动词组成并衔接条件副动词后缀的语义-语法复合词,几乎全部被用于编写言据性意义。此外,某些分析性句法构建也被使用,不过频率较小。由此可见,满语中言据性意义的编写,词汇和语法两方面因素均有涉及;这些语义-语法复合词和句法构建也可以被视为形塑满语言据性这一语法范畴的基础。本文的结论将有助于说明这一范畴是如何在跨语言的情境中产生和发展的。

論滿語中的言據性策略

Liliya M. Gorelova

俄國科學院與奧克蘭大學

Arthur Chen 陳辰

山東大學

“言據性”是語言學中最重要的範疇之一,本文將圍繞這一概念展開討論,並探討言據性在滿語語文中的表現形式。儘管是滿學研究界中涉足該領域的初次嘗試,本文仍然提出了幾項重要的發現和若干有意思的結論。我們特別發現,由信息和感官動詞組成並銜接條件副動詞後綴的語義-語法復合詞,幾乎全部被用於編寫言據性意義。此外,某些分析性句法構建也被使用,不過頻率較小。由此可見,滿語中言據性意義的編寫,詞匯和語法兩方面因素均有涉及;這些語義-語法復合詞和句法構建也可以被視為形塑滿語言據性這一語法範疇的基礎。本文的結論將有助於說明這一範疇是如何在跨語言的情境中產生和發展的。

1. Introduction

The category of evidentiality and its grammatical encoding have not yet been specially investigated in Manjuristics. This is largely due to the absence of evidentiality as a distinct grammatical category in the Manchu language. At first sight, evidentiality is expressed only lexically, mostly by certain independent verbs or lexical modifiers (or expressions). However, the whole situation is not so simple, and in this regard some very interesting issues can arise. By answering some important questions we can shed light on this field of knowledge not only in Manjuristics but also in Altaic studies more broadly, and even crosslinguistically. The issues are as follows: (1) the types of grammatical means of coding evidentiality; (2) the degree of grammaticalization of lexico-grammatical units used to express evidential meanings; (3) the origin and development of the evidential markers; (4) correlations with other grammatical categories, such as modality, tense-aspect system, transitivity/intransitivity of verbs, person, and clausal types; (5) connotations to conditionality as involved in expressing pragmatic properties in Manchu, kinds of discourse, and certain formal devises used to process information.

As is well known, the category of evidentiality was first proposed in the wake of the investigation of the American Indian languages and has been under discussion since the beginning of the nineteenth century.[1] However, the debate continues to this day concerning whether this category should be understood as a subcategory of the broader category of epistemic modality, as a speaker’s subjunctive assessment/knowledge of the likelihood of a given event,[2] or it should stand as a distinct category in its own right.[3] There exists a special point of view according to which certain evidential markers, especially those conveying the concept of inference, are considered to be borderline cases.[4] Witt argues that the verbs of auditory perception denoting both direct perception and hearsay meanings should not be seen as involved in the domain of epistemic modality.[5] In this paper we try to avoid this debate, if that is possible at all, while semantically defining the concept of evidentiality as the speaker’s indication of the source of information. At the same time, one cannot but admit that there exist certain semantic connotations of evidentiality with epistemic meanings related to the speaker’s attitude to the information (or knowledge), even if the latter are understood as the only semantic extensions (or secondary evidential-like meanings) of evidentiality. According to some authors, these additional semantic overtones can even be extended to the category of mirativity.[6]

In addition, some scholars mention certain correlations with other grammatical categories, namely, perfective or past tenses,[7] verbal transitivity/intransitivity, and person.[8]

As a grammatical category, evidentiality is considered obligatory for uttering every utterance in a language. This category possesses a set of grammatical devices, which form a grammatical paradigm. Concerning the morphological status of evidential markers, scholars point out that they can be (i) inflections, or (ii) clitics or other free syntactic elements.[9] Palmer singles out the following types of markers: (i) individual suffixes, clitics, and particles, (ii) inflection, and (iii) modal verbs.[10]

2. Evidential concepts in Manchu

The lexical verbs used to express the concepts of evidentiality in Manchu normally concern the processing of information, be it perceptive or intellectual by its nature; that is, the search for information, its reception, storage, and transmission, as well as cognitive operaterations performed with that information (the so-called IOI-verbs).[11] These meanings are represented by cognition verbs (speech, thought, investigation, memory, inference) and perception verbs (sight, hearing, feeling, smelling, etc.) as well.[12]

We have found the following independent verbs concerning the expression of different meanings of evidentiality: tuwa- “to look (at)”; donji- “to listen/hear”; gūni- “to think/consider”; baica- “to investigate”; bodo- “to calculate/consider”; kimci- “to look carefully/examine”; taka- “to recognize/know”; amtala- “to taste.”

The first two of them, namely, tuwa- and donji-, are used most frequently. This fact is in complete accordance with the data obtained by Witt, who investigates the evidential uses of perception verbs hear and sound in English and German.[13] Based on the perception verb hierarchy established by Viberg,[14] Witt argues that verbs of visual and auditory perception are supposed to be characterized by a higher degree of polysemy, and that fact entails a higher frequency in their usage.[15] Witt examines the transitivity/intransitivity of verbs, as this is the most important property of perception verbs that allow evidential readings. As a general tendency, subject-oriented (intransitive) verbs express evidential meanings with grammatical subjects (perceivers) that have the form of the first person. Object-oriented (transitive) verbs may be used evidentially with subjects in the form of the second and third persons.[16]

What is most interesting is that all of these verbs that function to indicate the source of information normally occur in the form of the so-called conditional converb (V-ci) in Manchu. We can observe a tendency for this form to occupy the left-dislocated (topical) position in an utterance. Since this form plays a crucial role in encoding evidentiality, we intend to define its important features at least in general way. Prototypical conditional constructions, consisting of the protasis (expressed by a subordinate clause containing a conditional converb as a predicate) and the apodosis (expressed by a main clause containing a main predicate of an utterance), are used to denote such relationships between two states of affairs that the realization of one state of affairs (represented in the protasis) serves as the condition for the realization of another state of affairs (represented in the apodosis). On the other hand, conditionals can convey several other meanings (e.g., causal, temporal, and concessive) and perform other functions (e.g., topicalization, textual connection).[17]

The conditional converb shares categorial properties intrinsic to all converbs. The defining attribute of converbs (as a subclass of non-finite verbal forms) is to denote the subordination of one verb form to another. As opposed to the verbs proper, converbs cannot serve as predicates in simple sentences or in the main clauses of complex sentences. Like all other converbs, the conditional converb possesses the grammatical categories of tense and person, which, however, have a relative nature. It means that the temporal characterization of converbs depends on the temporal specifications of the verb used as the main predicate in an utterance. A converb may share the same subject with the main verb, but it may also have its own subject referentially independent of the subject of the main verb. This subject, however, due to special features of Manchu grammar, may either be expressed by a nominal or be inferable from the previous syntactic context.[18] There is a very special usage of conditionals when they do not indicate a specific reference to any agent (experiencer/perceiver). In this particular case the agent (experiencer/perceiver) may not be indicated at all and is thus obscured from the discourse.

2.1 Visual (direct) versus inferred (indirect) evidential types

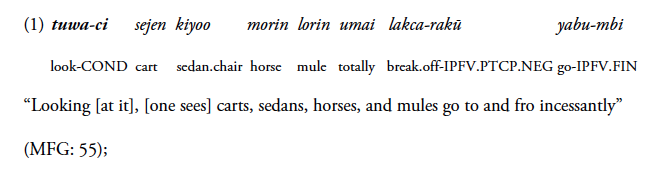

Visual evidentiality meaning (direct evidence from seeing) is encoded by the non-finite form tuwaci. Derived from the verbal stem tuwa- together with the suffix of the conditional converb -ci, this verbal form is designed – first of all – to signal that the information was acquired through visual perception. We can observe a tendency for these forms to occupy the left-dislocated (topical) position in an utterance:

The same conditional converb tuwaci may disclose the meaning of inference due to the polysemy of the verb itself. This is not surprising: the inferential interpretation here is possible because the inference is drawn on the basis of sensory (visual) evidence. So in Manchu this single word form may indicate that the information was received either from seeing (visual) or from inferring (deductive). However, in some cases it is not easy to draw a boundary between indications of these two sources of information (knowledge), namely, from seeing or inferring. Here are some examples when the left-dislocated converbal form tuwaci has the meaning of inference:

The form tuwaci, being verbal in its nature, may take its own complement, either nominal or predicative. Sentence (5) has shown this. Here are some examples in which the converb tuwa-ci governs nominals (personal pronominal or proper name) through the accusative marker be and reveals either visual ([7] – [8]) or inferential ([9] – [10]) interpretation:

The form tuwaci can govern participles, which can function as noun analogues:

The predicative complement governed by the conditional converb tuwaci through the accusative marker be should be syntactically specified as a subordinate clause. The following are some examples:[19]

In (13) the word form tuwa-ci governs the predicative compliment gucuse gemu simbe leolehe “all your friends have been talking about you” through the accusative marker be. The sense of uncertainty caused by the inferred reading of the converb tuwa-ci is strengthened by the modal particle dere “probably.”

Through governing the noun arbun “shape/form,” “appearance” by means of the accusative marker be, a stable adverbial phrase arbun be tuwaci ‘in view of the circumstances’ has been developed, which possesses the evidential meaning:

The converb tuwaci may be extended with adverbial phrases:

| (18) | sangga deri dosi tuwa-ci, ere tede darabu-mbi, tere ede bedere-bu-mbi |

| hole ABL inside look-COND this there invite.to.drink-IPFV.FIN that here return-CAUS-IPFV.FIN | |

| tede: 1) DAT of tere “that”; 2) “there, in that place”; 3) “up till now” | |

| ede: 1) DAT of ere “this”; “to this, here, then, in this (matter)” | |

| darabu-: “to invite to drink, “to offer a toast,” “to serve (wine)” | |

| bederebu- : 1) CAUS of bedere- “to return,” “to withdraw (at the court or at a ceremony),” “to die (of a noble personage)”; 2) “to send back,” “to withdraw,” “to refuse,” ‘to return a courtesy or gift” |

The verb tuwa- can occur in the dative participial form, which – as conditionals – can convey temporal and conditional meanings and is used to indicate inferred information, as in the following sentence:

Similarly to the converb tuwa-ci, the participial form can govern the word arbun through the accusative marker, resulting in the structure arbun be tuwahade “in view of the circumstances”:

From the perspective of evidentiality strategy there are several issues that should be noted with regard to the verb tuwa- “to look,” “to look at,” and – probably – other perception verbs. We suspect that, in order to express evidentiality, the perception verbs should not exhibit a very strong actionality but only describe an act of perception in a general and abstract way. Thus, for example, in sentence (21) the perception verb tuwa- “to look” indicates a specific, intentional act of perceiving and might be too strong to be considered a lexical expression of evidentiality. We think, in contrast, that the perception verb tuwa- in the evidentiality function should not describe a specific act of perception. In English a similar phenomenon does exist: the transitive verb look as in “I looked at the picture” versus the linking function of the verb look as in “The picture looked beautiful”; or the transitive verb listen as in “I am listening to Shostakovich” versus the verb sound as in “That symphony sounds marvelous.” The examples of look (in the first sentence) and listen are not evidential, but the other two are indeed evidential (lexically). Manchu does not have verbs like sound or look in the evidential use, but the verb tuwa- can perform such a function when it exhibits weak actionality. Here is an example in which the verb tuwa- does exibit a strong actionality, in other words, the act of observation:

Strictly speaking, the verb tuwa- “to look” cannot be qualified as a perception verb proper, since it denotes the act of observation rather than perception, while the visual perception is expressed by another verb, sabu- “to see.” The observation verb tuwa- in its semantic pattern could be extended to mean perceiving and processing information ‒ seeing, finding, realizing, understanding it, namely, “to look and (see, find, realize, understand something, etc.).”

We can adduce examples with the perception verb sabu- “to see,” which expresses the visual perception in sentences with compliment clauses where dependent predicates are expressed by participles in accusative:

Evidentiality is not expressed in these sentences: the states of affairs follow the visual perception temporally, and they are represented as facts. They are neither what the speakers perceive nor inferences/conclusions based on visual perception. In particular, in (22) and (24), the subject of the perception verb does not refer to the speaker. However, these sentences are used here to illustrate the usage of the perception verb sabu-.

On the other hand, acts of listening and auditory perception are expressed by the verb donji- “to listen/hear.” Due to their syntactic similarity and their relationship to perception, verbs such as tuwa- and donji- are all considered to be perception verbs here.

2.2 Auditory evidentiality and hearsay

Information/knowledge may be acquired through hearing (direct evidence, auditory evidential meaning). In Manchu the second most frequent word form used to express (lexical) evidential meaning is the conditional converb donji-ci (of the verb donji- “to listen,” “to hear”). This form is very often used to indicate hearsay information (indirect evidence).[21] Here are some examples where the word form donjici indicates auditory evidence (25) or hearsay (26):

The converb donji-ci may govern its own complement, either nominal or participial, through the accusative marker be (see sentence [27]). A participle, together with other components, may constitute a predicative construction that serves as a subordinate (complement) clause (see sentence [28]):

In this example the conditional converb donjici governs the clause niyalmai alara “what people tell” through the accusative marker be.

However, more frequently the converb donjici is used to express the “hearsay” meaning together with one of the forms of the quotative verb se- “say,” forming an analytical construction donjici … se- (lit.: “if I listen, they say”):

The “hearsay” meaning can be expressed by dative participial structures of the verb donji- “listen/hear.” These include donji-ha-de ([34]) and donji-ha ba-de ([35]):

1 Giovanni Stary, Emu tanggû orin sakda-i gisun sarkiyan – Erzählungen der 120 Alten. Beiträge zur mandschurischen Kulturgeschichte (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1983), 442.

1 Giovanni Stary, Emu tanggû orin sakda-i gisun sarkiyan – Erzählungen der 120 Alten. Beiträge zur mandschurischen Kulturgeschichte (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1983), 442.The verb donji- may appear in some verbal forms other than conditionals, including the finite ones (36), and govern the complement clauses. It seems that in such sentences they represent their content as indirect information:

2.3 Gustatory evidentiality

Information can be obtained by the speaker (perceiver) by means of the gustatory sense. The following are two examples:

One can notice that the verb amtala- “to taste” also includes in its semantic structure the meaning of realization of the act of perception: “To taste something and obtain the result of the tasting.”

2.4 Inference from the intellectual processing of information (indirect, second-hand evidence)

Quite a number of verbs occur in the form of the conditional converb to indicate that the inferences are obtained from the processing of information by means of human beings’ intellectual abilities to think, to investigate, and to reason: gūni- “to think”; baica- “to investigate,” “to examine,” “to find out”; bodo- “to calculate,” “to figure”; kimci- “to look carefully,” “to check,” “to examine”; taka- “to recognize,” “to know.” They are probably used in their lexical meaning and frequency of usage to form the third group of evidential meanings in Manchu. Obviously, the most widespread conditional converb among these non-finite verb forms is gūni-ci:

At the same time, one can see that the form gūnici, in addition to referring to the source of knowledge, also exposes the strongly pronounced epistemic overtone of uncertainty and probability regarding this knowledge (speculative epistemic modality). In some sentences such overtones are strengthened by special particles with the same meanings; in (43) it is the particle dere “probably.”

The verbal form baicaci (baica- “to investigate” followed by the suffix of the conditional converb -ci) is used to indicate that the information is obtained through the process of investigation and should be accepted as a result of this kind of mental activity. The construction headed by the form baicaci is particularly frequent in the official memorials submitted to the Manchu Emperors:

The internal semantic structure of the verb baica- is also supposed to be extended by the realization of an act: we investigated and (found, realized, etc.).

The next few converbal forms which have very close semantic meanings to the ones mentioned above are not so frequent, but at least we have found several examples in our materials. These forms can be either left-dislocated or preceded by dependent words. Governing their own predicative complements, they can build syntactic constructions that serve as subordinate (complement) clauses. Here are some example with the converbs bodo-ci, fonji-ci, and taka-ci:

Presumably, the list of converbal forms with similar lexico-semantic and evidential functions can go beyond what we have already discussed. It is only a matter of the quality and quantity of data.

3. Explications

3.1 The grammatical means of encoding evidentiality

As can be observed from language material, evidential meanings are most often expressed by the form of conditional converbs (V-ci) derived from verbs with IOI-semantics (the information verbs). Participles in Dative case can encode evidential meanings (Tv- -rA/-hA-de) as well; however, it is more infrequent. That is to say that both factors, lexical and grammatical, contribute to the expression of evidential meanings in Manchu. In evidential function these converbal forms exhibit a tendency to occupy the left-dislocated position in the sentence, which is also topical.

To those grammatical types of markers that are used to encode evidential meanings and mentioned by scholars, namely individual suffixes, clitics and particles, and inflection and modal verbs, we can add a syntactic analytical construction. As shown above, inferred and reported evidentiality meanings reveal a tendency to be encoded by the syntactic construction “donjici . . . se-,” where the first component is the form of conditional converb derived from verbs with IOI-semantics, and the second one is an indicative verbal form from the verb se- “to say.”

This kind of marking is neither totally obligatory nor completely grammaticalized, and can be thought of as evolving, like many other grammatical notions and categories in Manchu.

3.2 The degree of grammaticalization of lexico-grammatical units used for expression of evidential meanings

This question is partly discussed under the previous point. As stated above, conditional converbs and the dative participial structure may take predicative complements. The resulting syntactic constructions can be analyzed syntactically as clausal, semantically as propositional, and pragmatically as presupposed (in most cases). Here are examples where a conditional converb governs a clausal construction (see also examples 13–14):

In this sentence the conditional converb tuwaci governs the complement clause with the predicate expressed by the imperfective participle in the accusative case.

In this sentence the conditional converb tuwa-ci governs the complement clause whose predicate is expressed by the negative form of perfective predicate in the accusative.

When used alone and placed in the left-dislocated position, these converbal forms reveal much more independence from grammatical context. The degree of grammaticalization of left-dislocated forms should be considered higher than that of those occurring as governing clausal constructions. An even higher degree of grammaticalization exists when these forms developed into textual connectors losing much more of their lexical meanings (see point 3.6 below).

3.3 The origin and development of evidential markers

Strictly speaking, the sentences having left-dislocated verbal forms used to convey evidential meanings can be replaced – in certain cases – by complex sentences that consist of two clauses (two propositions). One of them can be analyzed as a main clause with the predicate encoded in IOI-verbs, which can be viewed as the expression of a kind of perceiving information and the act of perceiving as well. The other proposition (more exactly, the first one) is used to assert what is perceived and processed through certain human mental abilities. This proposition is expressed by the subordinate clause, which can be specified as a predicative complement governed by the main predicate through the accusative case:

A number of authors have already stated that evidential markers can develop from independent verbs through the process of grammaticalization. The evidential markers can be seen as evolution of the verbs with IOI-semantics (information/communication verbs) used as main predicates in complex sentences, which are understood here as the relationship between clauses, both main and subordinate (complement in our case). Over time the compound sentences themselves could be reduced to simple ones as the result of this process. In other words, a complement clause can be reanalyzed as a main clause; at the same time, a verbal form previously used to denote a main predicate acquires an evidential function. Most often evidential markers can be derived from the perception verbs (mostly verbs of sight, hearing, and feeling), as well as from the verbs of speech.[23] The detailed analysis of such processes can be found in Aikhenvald.[24] If the main function of complex sentences with main predicates expressed by verbs of information should be seen as making an assertion about states of affairs, the evidential developed from such verbs is characterized by a different function that should be defined as the indication of sources of information. Generally speaking, the process of evolution and the development of evidentiality markers can be seen in some evidentiality systems “as the result of reanalysis of a complementation strategy.”[25]

Recently some interesting data have come from analyzing eventuality in Kalmyk, in which the reportative evidential particle ginä can be seen as a grammaticalized form of the quotation verb gi- (present form 3sg.pl gi-nä). In certain circumstances a compound sentence with main and complement clauses could be reduced to a simple clause, and the verb of quotation gi-nä functioning as the main predicate had changed its grammatical status into a particle used to encode the reported information. In such particular cases the particle ginä appears with the only possible verbal form in -ž, which is indirective synthetic form.[26]

3.4 The categories of person and tense in relation to evidential expressions

The IOI-verbs (in particular perception and cognition verbs) should be examined in terms of what conditions need to be satisfied, in order to express evidentiality, by the various facets of these verbs: tense, person, and actionality.

This problem can be approached from the evidential function of the verbs of perception/cognition – indicating the speaker’s source of information. This means that the perception/cognition should be performed by the speaker, i.e., the perceiver/cogniser should be referentially identical with the speaker of the sentence. This is the reason why the first person is mostly used in these sentences, translated as “I see,” “I hear,” etc. In contrast, when the perceiver/cogniser is different from the speaker, no evidential meaning is expressed, since the speaker is only asserting that someone else performs perception/cognition. The following are examples of this type:

In the first sentence above, the subject of the verb tuwa- “to look” is an old man in the story, while in the second sentence, the subject of the verb donji- “to listen” is the Nishan Shamaness. In both cases the subject of the verb of perception is different from the speaker, who only narrates what the story characters perceive. The speaker (narrator) does not by any means indicate the source of his information about the story. Therefore, the verbs of perception do not express the evidential meaning.

However, due to the lack of a morphological category of person in Manchu and, as a consequence, the absence of personal suffixes in the linear structure of verbal forms, it is usually impossible to determine the subject of the verb of perception merely through examining the conditional converb. In fact, morpho-syntactically the two sentences are not distinct from (6) and (25), respectively, which do express the evidential meanings. Thus, the subject of the verb of perception/cognition needs to be decided either by an explicit subject (see [15]), or from the context.

Apart from the case in which the speaker is referentially identical with the perceiver/cogniser, it is also possible to express evidentiality when the verb of perception does not have a specific subject but a general, unspecified subject. One such case is (1–2, 5, etc.) where the verb tuwa- “to look” has an unspecified subject: it does not necessarily describe a specific event of visual perception performed by the speaker. However, the probability still remains high that the speaker bases his information on visual perception. In other words, the speaker is still a highly “potential” perceiver.

As far as the category “tense” is concerned, we notice that in principle, evidentiality does not impose restrictions on the time of the perception: the speaker should be able to indicate his source of information either from the past or the present. For instance, in the case of tuwa- “to look,” (8) concerns the present, while (3, etc.) concern the past. In the case of donji- “to listen,” (29, etc.) concern the present, while (30) concerns the past. It should be noted that since the perception verbs are either in the form of conditional converb V-ci or the participle in dative V-hA de, both of which represent a relative temporal relation to other verbs, their temporal location has to be considered in combination with the verb form of the main clause.

3.5 Connotation to pragmatic categories and the type of discourse

It has already been stated that evidentials can be directly associated with a pragmatic function in some languages and can be considered “communication-advancing material.”[27]

In Manchu, the conditional converb definitely contributes to advancing information in discourse. The conditionals do this in two ways. First, the conditional suffix -ci together with existential verbs bi- and o-, as well as quotative verb se-, are used to build topic markers (bici, oci, seci).[28] Second, conditional (and in certain cases temporal) clauses whose predicative heads contain corresponding converbs expressed by full semantic verbs can represent the theme (topic) of utterances themselves. This is quite understandable, since in certain semantic contexts conditional (and temporal) constructions may express the given (presupposed) information with respect to the rest of an utterance in the manner typically performed by a topic.[29]

When occurring in the left-dislocated position, the converb in question also serves to advance the expression of information. Referring to the notion of communicative dynamism (CD) introduced by J. Firbas and understood as “the extent to which the sentence element contributes to the development of the communication,” we can state that these forms play a great role in the organization of the text as the delivery of information.[30] Performing this function, these forms are very close to those that we identify as textual connectors. Sometimes it is difficult to drawn the boundary between converbs (as well as dative participial structures) used to express the evidential meanings and textual connectors. The latter can be understood as characterized by a higher degree of grammaticalization than the former as well as developing a new – in a certain sense – function.

As for the kind of discourse, in which converbal forms often occur, we can mostly find them in tales, folklore, and narration. They are typically used for highlighting the most important aspects and events in narratives.

3.6 Textual connectors in Manchu

Textual connectors are understood here as language elements, of a different degree of grammaticalization, which are used to advance information in discourse. Designed to connect sentences (utterances) in discourse, they serve to progress from thematic material (topic, old information) to rhematic material (focus, old information). Being left-dislocated elements, textual connectors are used to refer to rhematic material that has already been stated in a previous sentence (utterance) and thus becomes familiar to the hearer. At the same time such connectors are used to mark textual boundaries beginning a new episode (rhematic material) in a discourse.

Among textual connectors in Manchu, there are those that disclose obvious semantic and structural connections to the language elements involved in the encoding of the evidentiality strategies as well as those that do not transparently display such connections. The latter, however, obviously reveal the connection to presupposed language elements, mostly conditionals (and sometimes language units, which have temporal meaning). Each group includes several structural types of such elements.

Structurally, the first group includes participles, both perfective and imperfective, in the dative, which are derived from the IOI-verbs (verbs of information), such as tuwa-, se-, gisure-, and which are obviously engaged in the encoding of evidentiality meanings. Here are some examples:

The perfective participle takes the demonstrative pronoun ere “this” in the form of genitive case; this pronoun has referential function and, together with the dative participle, refers to the previous episode of discourse and thus makes familiar to the hearer the previous information.

This subgroup also may include converbs oci and seme (conditional and imperfective correspondingly), which are preceded by pronominal words, which can be defined as the demonstrative adverbs uttu “like this,” and tuttu “like that”:

The combination tuttu seme in this sentence means “even so,” with a concessive tone.

The verb o- “to become/to be” can occur in the form of the perfective participle in the dative case, which is o-ho-de:

The demonstrative adverb uttu may be followed by the negative particle waka, and together with the existential conditional they form a stable phrase uttu waka oci “otherwise”:

A connector may consist of several components, which all together are used to denote the concessive meaning. The connector udu tuttu bicibe “although it is like that,” “despite that” represents a kind of language unit that includes the concessive connector udu “although,” the demonstrative adverb tuttu “like that,” and the form of the concessive converb derived from the existential verb bi- “to be”:

The second group of clausal connectors differs by its origin and semantics. The conditional converb oci is preceded by the expression mini gūnin de “in my opinion” (gūnin “intention,” “thought,” “opinion,” “sense”; “mind,” “spirit”). In addition to the indication of the source of information, language units of this kind definitely expose the epistemic modal meaning of uncertainty about the proposition that reflects events in the outside world. Here are a couple of examples:

4. Conclusions

The category of evidentiality has not been thoroughly investigated in the Manchu language. Though this is a preliminary study, we can make some statements regarding major properties of the semantic area, which include evidential meanings.

- 1) We have not discovered any evidence that evidentiality exists as a fully grammatical category.

- 2) Most evidential meanings/strategies in Manchu are encoded in lexical independent verbs with IOI-semantics, which are information verbs, in particular perception and cognition ones. Most importantly, to such verbal stems is attached the suffix of the conditional converb (-ci), grammatical features of which entail some essential issues. Occupying the left-dislocated position in the sentence, such semantico-grammatical complexes have the potential to develop the basis for the formation of the grammatical category of evidentiality as such. In addition, they often occur in combination with finite forms of the quotative verb se- “to say,” especially in the case of the verb donji- “to listen,” “to hear,” building a kind of analytical construction “donji-ci … se-” (lit. “if I listen, they say”) and expressing the hearsay meaning.

The verbs tuwa- and donji- can appear in the dative form (marker de) of the perfective participle, which – as conditionals – can convey temporal and conditional meanings and be used to indicate inferred information.

- 3) The information (perception/cognition) verbs are characterized by a complex semantic structure, which includes not only the act of observation (auditory, visual, gustatory, cognitive, etc.), but also the realization of perception. In other words, the semantics of the verbs tuwa-, donji-, amta-, etc., in most cases are extended by the expression of the realized acts (look, listen, taste, seek and then see, hear, taste, find; realize, understand, etc.).

- 4) The verbs tuwa- and donji- are the most frequent verbs for denoting evidential meanings. These verbs are the most multi-functional ones, and therefore may denote both direct (visual, hearing, etc.) and indirect (reported, inferred, etc.) knowledge.

- 5) The verb tuwa- cannot be considered a proper perception verb but an observation one. In Manchu there is a real perception verb, sabu- “to see,” which denotes visual perception. This verb governs a predicative complement conveying the state of affairs of the outside world, which is the object of perception.

- 6) A number of expressions built on the basis of IOI-verbs are used to link sentences in discourse and to advance information in it. We call them “textual connectors” and believe that they are further grammaticalized among the semantico-grammatical complexes used to encode evidential meanings.

List of Abbreviations

1/2/3 – 1st/2nd/3rd person; ABL – ablative, ACC – accusative; ASP – aspect; AUX – auxiliary verb; CAUS – causative; CNJ – conjunction; CONC – concessive; COND – conditional; COP – copula; CVB – converb; DAT – dative; FIN – finite; EXCL – exclusive; GEN – genitive; IMP – imperative; INCL – inclusive; IPFV – imperfective; NEG – negative; NR – nominalizer; OPT – optative; PASS – passive; PFV – perfective; PL – plural; PN – proper noun; PTCL – particle; PTCP – participle; PST – past; SG – singular; TP – toponym (place-name)

Manchu Materials Analyzed

- AGA Aisin-Gioro, Ihing. An i gisun i amtan be sara bithe (The book for knowing the taste of ordinary language). 4 vols. Beijing, 1802.

- LQD Qingyu Laoqida 清語老乞大 (Laoqida: a Manchu translation). Ed. Zhuang Jifa 莊吉發 [Chuang Chi-fa]. Taipei: Wenshizhe Chubanshe, 1984.

- MFG Uge Šeoping. Nikan gisun kamciha manjurara fiyelen i gisun (Passages ofManchu dialogues with Chinese translation). Cing wen ki mung bithe 2 (Anelementary textbook of Manchu). Beijing: Sanhuaitang, 1730.

- MYK Manjui yargiyan kooli (Veritable records of the Manchus). 8 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1985.

- NSBNišan samani bithe (The tale of the Nišan Shaman). Publication, translation, and preface by M. P. Volkova. Moscow: Vostochnaya literatura, 1961.

- OJ1 Zhang Huake張華克. Sume hūlara manju gisun i oyonggo jorin i bithe, Qingwen zhiyao jiedu淸文指要解讀 (Essentials of the Manchu language with Chinese annotation). Taipei: Wenshizhe chubanshe, 2005.

- OJ2 Zhang Huake張華克. Sume hūlara sirame banjibuha nikan hergen i kamcibuha manju gisun i oyonggo jorin i bitheuha manju gisun i oyonggo jorin i bithe, Xubian jian Han-Qingwen zhiyao jiedu 續編兼漢清文指要解讀 (Recompiled essentials of the Manchu language with Chinese annotation). Taipei: Wenshizhe chubanshe, 2005.

- R-Li Roth-Li, Gertrude. Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents. 2d ed. Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center, University of Hawai’i Mānoa, 2010.

- UG Houtian Wanfu 厚田萬福 and Liu Fengshan 劉鳳山. Dasame foloho manju gisun i untuhun hergen i temgetu jorin i bithe, Chongke Qingwen xuzi zhinanbian 重刻清文虚字指南編 (Essential functional words in Manchu: A reprint). Beijing: Longfusi juzhentang, 1894.

Works Cited

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. Evidentiality. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ------. “Evidentiality in Typological Perspective.” In Studies in Evidentiality, edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon, pp. 1-31. Typological Studies in Language 54. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2003.

- Anderson, Lloyd B. “Evidentials, Paths of Change, and Mental Maps: Typologically Regular Asymmetries.” In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, edited by Wallace Chafe and Johanna Nichols, pp. 273-312. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1986.

- Chafe, Wallace. “Evidentiality in English Conversation and Academic Writing.” In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, edited by Wallace Chafe and Johanna Nichols, pp. 261-72. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1986.

- Chen, Arthur. “Conditional Constructions in the Manchu Language: A Study from the Perspectives of Semantics, Morphosyntax, Pragmatics and Typology.” Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Auckland, 2013.

- Cheremisina, M. I., L. M. Brodskaja, and L. M. Gorelova, et al. Predicativnoe sklonenie prichastij v altajskich jazykach (Predicative declension of participles in the Altaic languages). Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1984.

- Comrie, B. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Daneš, František. “Functional Sentence Perspective and the Organization of the Text.” In Papers on Functional Sentence Perspective, edited by F. Daneš, pp. 106-28. Prague: Academia, 1974.

- de Haan, Ferdinand. “Evidentiality and Epistemic Modality: Setting Boundaries.” Southwest Journal of Linguistics 18 (1999): 83–101.

- ------. “The Place of Inference within the Evidential System.” International Journal of American Linguistics 67 (2001): 193–219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/466455

- ------. “Typological Approaches to Modality.” In The Expression of Modality, edited by William Frawley, pp. 27-69. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110197570.27

- Firbas, Jan. “On Defining the Theme in Functional Sentence Analysis.” Travaux Linguistiques de Prague 1 (1964): 267-80.

- ------. “On the Concept of Communicative Dynamism in the Theory of Functional Sentence Perspective.” Sbornίk pracί filozofické faculty Brněnské University. Series Linguistica A 19 (1971): 135-44.

- ------. “Some Aspects of the Czechoslovak Approach to Problems of Functional Sentence Perspective.” In Papers on Functional Sentence Perspective, edited by F. Daneš, pp. 11-37. Prague: Academia, 1974.

- Gordon, Lynn. “The Development of Evidential in Maricopa.” In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, edited by Wallace Chafe and Johanna Nichols, pp. 75-88. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1986.

- Gorelova, Liliya M. Manchu Grammar. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

- ------. “Typology of Information Structures in the Altaic Languages.” In Kinship in the Altaic World, Proceedings of the 48th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Moscow 10-15 July, 2005, edited by Elena V. Boikova and Rostislav B. Rybakov, pp. 149-71. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2006.

- ------ and Mariya N. Orlovskaya. “The Proximity between the Middle Mongol and Classical Manchu Languages as Typologically, Ethnohistorically and Areally Motivated.” In Unknown Treasures of the Altaic World in Libraries, Archives and Museums: 53rd Annual Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, RAS, St. Petersburg, July 25-30, 2010, edited by Tatiana Pang, Simone-Christiane Raschmann, and Gerd Winkelhane, pp. 329-49. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz, 2013.

- Halliday, M. A. K. “Notes on Transitivity and Theme in English, Part 3.” Journal of Linguistics 3 (1967): 199–244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022226700016613

- Jacobsen, William H., Jr. “The Heterogeneity of Evidentials in Makah.” In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, edited by Wallace Chafe and Johanna Nichols, pp. 3-28. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1986.

- LaPolla, Randy J. “Evidentiality in Qiang.” In Studies in Evidentiality, edited by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon, pp. 63-78. Typological Studies in Language 54. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2003.

- Mithun, Marianne. “Evidential Diachrony in Northern Iroquoian.” In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, edited by Wallace Chafe and Johanna Nichols, pp. 89-112. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1986.

- Palmer, F. R. Mood and Modality. 2d ed. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139167178

- Skribnik, Elena, and Olga Seesing. “Evidentiality in Kalmyk.” In The Grammar of Knowledge: A Cross-Linguistic Typology, edited by Alexandra Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon, pp. 149-70. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198701316.003.0007

- Stary, Giovanni. Emu tanggû orin sakda-i gisun sarkiyan – Erzählungen der 120 Alten. Beiträge zur mandschurischen Kulturgeschichte. Asiatische Forschungen 83. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1983.

- van der Auwera, J., and V. A. Plungian. “Modality’s Semantic Map.” Linguistic Typology 2 (1998): 79-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/lity.1998.2.1.79

- Viberg, Å. “The Verbs of Perception: A Typological Study.” Linguistics 21 (1983): 123-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ling.1983.21.1.123

- Weber, David J. “Information Perspective, Profile, and Patterns in Quechua.” In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, edited by Wallace Chafe and Johanna Nichols, pp. 137-55. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1986.

- Witt, Richard J. “Auditory Evidentiality in English and German: The Case of Perception Verbs.” Lingua 119 (2009): 1083–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.11.001

Notes

The history of investigation of the category of evidentiality can be found in William H. Jacobsen, Jr., “The Heterogeneity of Evidentials in Makah,” in Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, ed. Wallace Chafe and Johanna Nichols (Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1986), 3-28. As he – as well as some others – states, the process itself began with the publication of numerous works by Franz Boas, who is considered a pioneer in this field of language structures: “Heterogeneity of Evidentials in Makah,” 3-7; Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, “Evidentiality in Typological Perspective,” in Studies in Evidentiality, ed. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2003), 1.

See, for example, Wallace Chafe, “Evidentiality in English Conversation and Academic Writing,” and other papers in Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology; F. R. Palmer, Mood and Modality, 2d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Ferdinand de Haan, “Evidentiality and Epistemic Modality: Setting Boundaries,” Southwest Journal of Linguistics 18 (1999): 83–101, “The Place of Inference within the Evidential System,” International Journal of American Linguistics 67 (2001): 193–219, “Typological Approaches to Modality,” in The Expression of Modality, ed. William Frawley (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2006), 27-69; Aikhenvald, “Evidentiality in Typological Perspective,” Aikhenvald, Evidentiality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

J. van der Auwera and V. A. Plungian, “Modality’s Semantic Map,” Linguistic Typology 2 (1998): 79–124.

Richard J. Witt, “Auditory Evidentiality in English and German: The Case of Perception Verbs,” Lingua 119 (2009): 1083–95.

B. Comrie, Aspect (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 108; Palmer, Mood and Modality, 13-14; Aikhenvald, “Evidentiality in Typological Perspective,” 16-17.

Lloyd B. Anderson, “Evidentials, Paths of Change, and Mental Maps: Typologically Regular Asymmetries,” in Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, 275.

The term was firstly introduced by M. Cheremisina. See M. I. Cheremisina, L. M. Brodskaja, and L. M. Gorelova, et al., Predicativnoe sklonenie prichastij v altajskich jazykach (Predicative declension of participles in the Altaic languages) (Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1984).

It is not unusual to specify the source of information (and quality of it) with the help of predicate evidentials. In the Northern Iroquoian language, for example, evidentiality is expressed by evidential suffixes related to the tense system, a set of evidential particles, and partly through overt predicates with meanings such as “think,” “say,” “tell,” “certain,” “true”: Marianne Mithun, “Evidential Diachrony in Northern Iroquoian,” in Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, 97.

Å. Viberg, “The Verbs of Perception: A Typological Study,” Linguistics 21 (1983): 123-62.

Witt, “Auditory Evidentiality in English and German,” 1085-86. According to Viberg, a verb which occupies the higher position in the hierarchy scale (to the left) normally is characterized by an extended lexical semantics that covers the meanings of verbs lower (to the right) in the hierarchy: Sight > Hearing > Touch > {Smell, Taste}. Viberg, “Verbs of Perception,” 136.

Witt, “Auditory Evidentiality in English and German,” 1085-86, etc.

Arthur Chen, “Conditional Constructions in the Manchu Language: A Study from the Perspectives of Semantics, Morphosyntax, Pragmatics and Typology,” unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Auckland, 2013; Liliya M. Gorelova, “Typology of Information Structures in the Altaic Languages,” in Kinship in the Altaic World, Proceedings of the 48th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Moscow 10-15 July, 2005, ed. Elena V. Boikova and Rostislav B. Rybakov (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2006), 149-71.

Liliya M. Gorelova, Manchu Grammar (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 267.

There is evidence that in Kalmyk, a Western Mongolic language, complement clauses with participles followed by markers of the accusative case as connectors always express indirect information (whether “hearsay” or the results of logical operations): Elena Skribnik and Olga Seesing, “Evidentiality in Kalmyk,” in The Grammar of Knowledge: A Cross-Linguistic Typology, ed. Alexandra Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 165-67, 169.

We adduce here an example from the Sibe language given by Roth-Li, Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents. No matter how we treat Sibe—as a dialect of Classical Manchu or as a separate language, it reveals – regarding this property – a strong resemblance to Written Manchu. Sentences (31, 34) are also taken from Sibe.

Other terms used for this kind of evidential source are “second-hand,” “linguistic evidence.”

Giovanni Stary, Emu tanggû orin sakda-i gisun sarkiyan – Erzählungen der 120 Alten. Beiträge zur mandschurischen Kulturgeschichte (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1983), 442.

See, for example, Lynn Gordon, “The Development of Evidential in Maricopa,” in Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, 75-88; Aikhenvald, “Evidentiality in Typological Perspective, 21; Randy J. LaPolla, “Evidentiality in Qiang,” in Studies in Evidentiality, 63-78. According to Gordon, there is a set of evidential suffixes used to indicate sensory sources of information, which transparently derived from the lexical verbs in the Maricopa language of Arizona, a member of the Yuman language family. The suffix used to indicate a visual source of information is seen as derived from the verb of sight, and the suffix for hearing and other non-visual sensory evidentials developed from the verb of hearing. Similarly, a reportative clitic is derived from the verb with meaning “say” (pp. 75-88). LaPolla also witnesses that the evidential marker used to indicate a reported source of information (hearsay) goes back to the grammaticalized verb ‘say’ in Qiang, a language classified as Tibetan (p. 70).

Aikhenvald, “Evidentiality in Typological Perspective,” 285.

David J. Weber, “Information Perspective, Profile, and Patterns in Quechua,” in Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology, 145-46. Constructing the notion of an “information profile,” which is used to characterize a sentence’s progress in discourse, Weber explores the Quechua language of Peru, referring to evidentials in this language, which are similar to the pragmatic categories theme/old information/topic vs. rheme/new information, and similar to material used to set the stage of discourse, or communication-advancing material (pp. 145-51).

In Manchu there are other topic markers that reveal different patterns of origin: Gorelova, Manchu Grammar, 404-14; Gorelova, “Typology of Information Structures in the Altaic Languages,” 149-71.

Liliya M. Gorelova and Mariya N. Orlovskaya, “The Proximity between the Middle Mongol and Classical Manchu Languages as Typologically, Ethnohistorically and Areally Motivated,” in Unknown Treasures of the Altaic World in Libraries, Archives and Museums: 53rd Annual Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, RAS, St. Petersburg, July 25-30, 2010, ed. Tatiana Pang, Simone-Christiane Raschmann, and Gerd Winkelhane (Berlin: Klaus Schwarz, 2013), 329-49.

Jan Firbas,“On Defining the Theme in Functional Sentence Analysis,” Travaux Linguistiques de Prague 1 (1964): 270, “On the Concept of Communicative Dynamism in the Theory of Functional Sentence Perspective,” Sbornίk pracί filozofické faculty Brněnské University. Series Linguistica A, 19 (1971): 135-44, “Some Aspects of the Czechoslovak Approach to Problems of Functional Sentence Perspective,” in Papers on Functional Sentence Perspective, ed. F. Daneš (Prague: Academia, 1974), 11-37; František Daneš, “Functional Sentence Perspective and the Organization of the Text,” in Papers on Functional Sentence Perspective, 106-7. The notion of CD was worked out within the framework of Functional Sentence Perspective Theory, introduced by the Prague linguistic school. The elements and properties of discourse pragmatics have also been studied within the Theory of Information Structure, a term introduced by M. A. K. Halliday in “Notes on Transitivity and Theme in English, Part 3,” Journal of Linguistics 3 (1967): 199–244.