Introduction: Towards a Finally Subjectless Object

Ordinarily, upon hearing the word “object”, the first thing we think is “subject”. Our second thought, perhaps, is that objects are fixed, stable and unchanging, and therefore to be contrasted with events and processes. The object, we are told, is that which is opposed to a subject, and the question of the relation between the subject and the object is a question of how the subject is to relate to or represent the object. As such, the question of the object becomes a question of whether or not we adequately represent the object. Do we, the question runs, touch the object in its reality in our representations, or, rather, do our representations always “distort” the object such that there is no warrant in the claim that our representations actually represent a reality that is out there. It would thus seem that the moment we pose the question of objects we are no longer occupied with the question of objects, but rather with the question of the relationship between the subject and the object. And, of course, all sorts of insurmountable problems here emerge because we are after all—or allegedly—subjects, and, as subjects, cannot get outside of our own minds to determine whether our representations map on to any sort of external reality.

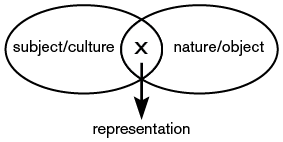

The basic schema both of anti-realisms and of what I will call epistemological realisms (for reasons that will become apparent in a moment) is that of a division between the world of nature and the world of the subject and culture. The debate then becomes one over the status of representation.

Within the schema of representation, object is treated as a pole opposed to subject. The entire debate between realism and anti-realism arises as a result of how these two circles overlap. While the overlap between these two domains seems to establish or guarantee their relation, this overlap also contains something of an antinomy or fundamental ambiguity. Because the representation lies in the intersection between the two domains, there's a deep ambiguity as to whether or not representation actually hooks on to the world as it really is. Epistemological realists seek a correspondence or adequation between subject and object, representations and states-of-affairs. They wish to distinguish between true representations and mere imaginings, arguing that true representations mirror the world as is, reflecting a world as it is regardless of whether any represents it. In short, epistemological realists argue that true representations represent a world that is in no way dependent on being represented by the subject or culture to exist as it does. Often epistemological realisms are closely connected with a project of Enlightenment critique, seeking to abolish superstition and obscurantism by discovering the true nature of the world and giving us the resources for distinguishing what is epistemologically justified and what is not.

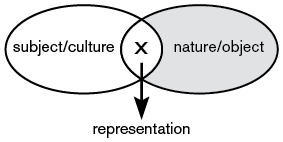

Anti-realisms, by contrast, note that our relationship to the world still falls within the domain belonging to the subject, mind, and culture:

Here the darkened space within the right-hand circle indicates that the domain of nature and the object has been foreclosed, that it's been blocked out, and that we are to restrict inquiry to what is given in the subject and culture circle. While the anti-realist generally does not deny that a world independent of subject, mind, and culture exists—i.e., he's not a Berkeleyian subjective idealist or a Hegelian absolute idealist—the anti-realist nonetheless argues that because representation falls entirely within the domain of the subject and culture we are unable to determine whether representations are merely our constructions, such that they do not reflect reality as it is at all, or whether these representations are true representations of reality as it is and would be regardless of whether it were represented. However, while the anti-realist argument generally bases itself on the indeterminability of whether representation is construction or a true representation of reality, it often slips into the thesis that representation is a construction and that reality is very likely entirely different from how we represent it. For the anti-realist, truth thus becomes inter-subjective agreement, consensus, or shared representation, rather than a correspondence between representation and reality. Indeed, the very concept of reality is transformed into reality for-us or the manner in which we experience and represent the world. Like epistemological realisms, anti-realisms are often closely connected to a project of critique. In this regard, they might seek to demonstrate the limits of what we can know, or alternatively they might attempt to show how “pictures” of the world are socially constructed such that they vary according to history, culture, language, or economic class. In this way, the anti-realist is able to debunk universalist pretensions behind many “world-pictures” that function to guarantee privilege.

As a consequence of the two world schema, the question of the object, of what substances are, is subtly transformed into the question of how and whether we know objects. The question of objects becomes the question of a particular relation between humans and objects. This, in turn, becomes a question of whether or not our representations map onto reality. Such a question, revolving around epistemology, has been the obsession of philosophy since at least Descartes. Where prior philosophy engaged in vigorous debates as to the true nature of substance, with or around Descartes the primary question of philosophy became that of how subjects relate to or represent objects. Nor were the stakes of these debates about knowledge small. At issue was not the arid question of when and how we know, but rather the legitimacy of knowledge as a foundation for power. If questions of knowledge became so heated during the Renaissance and Enlightenment period in Western philosophy, then this is because Europe was simultaneously witnessing the birth of capitalism, the erosion of traditional authority in the form of monarchies and the Church, the Reformation, the rise of democracy, and the rise of the new sciences. Questions of knowledge were political questions, simultaneously targeting arguments from authority that served as a support or foundation for the monarchies and the Church—the two of which were deeply intertwined—and laying the groundwork for participatory democracy through a demonstration that all humans have the capacity to know (Descartes and perhaps Locke) or that knowledge is not possible at all, but consists of merely sentiment, custom, or opinion (Hume).

In any event, the two options that opened Modernity—Descartes and Hume—led to much the same consequences at the level of the political: that individual humans are entitled to define their own form of life and participate in the formation of the State because either a) all humans are capable of knowing and therefore are not in need of special authorities or revelation to govern them, or b) that because absolute knowledge is unobtainable for humans, any authority claiming to ground his or her authority on the basis of knowledge is an illegitimate huckster bent on controlling and manipulating the populace. In short, behind this debate was the issue of egalitarianism or the right of all persons to participate in governance. In one form or another this debate and these two options continue down to our own time and are every bit as heated and political as when the shift to epistemology first arose. On the one hand we have the pro-science crowd that vigorously argues that science gives us the true representation of reality. It is not difficult to detect, lurking in the background, a protracted battle against the role that superstition and religion play in the political sphere. Society, at all costs, must be protected from the superstitious and religious irrationalities that threaten to plunge us back into the Dark Ages. Here The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins comes to mind. [2] On the other hand, there are the social constructivists and anti-realists vigorously arguing that our conceptions of society, the human, race, gender, and even reality are constructed. Their worry seems to be that any positive claim to knowledge risks becoming an exclusionary and oppressive force of domination, and they arrive at this conclusion not without good reason or historical precedent.

As always, the battles that swirl around epistemology are ultimately questions of ethics and politics. As Bacon noted, knowledge is power. And knowledge is not simply power in the sense that it allows us to control or master the world around us, but rather knowledge is also power in the sense that it determines who is authorized to speak, who is authorized to govern, and is the power to determine what place persons and other entities should, by right, occupy within the social order. No, questions of knowledge are not innocent questions. Rather, they are questions intimately related to life, governance, and freedom. A person's epistemology very much reflects their idea of what the social order ought to be, even if this is not immediately apparent in the arid speculations of epistemology.

Yet in all of the heated debates surrounding epistemology that have cast nearly every discipline in turmoil, we nonetheless seem to miss the point that the question of the object is not an epistemological question, not a question of how we know the object, but a question of what objects are. The being of objects is an issue distinct from the question of our knowledge of objects. Here, of course, it seems obvious that in order to discuss the being of objects we must first know objects. And if this is the case, it follows as a matter of course that epistemology or questions of knowledge must precede ontology. However, I hope to show in what follows that questions of ontology are both irreducible to questions of epistemology and that questions of ontology must precede questions of epistemology or questions of our access to objects. What an object is cannot be reduced to our access to objects. And as we will see in what follows, that access is highly limited. Nonetheless, while our access to objects is highly limited, we can still say a great deal about the being of objects.

However, despite the limitations of access, we must avoid, at all costs, the thesis that objects are what our access to objects gives us. As Graham Harman has argued, objects are not the given. Not at all. As such, this book defends a robust realism. Yet, and this is crucial to everything that follows, the realism defended here is not an epistemological realism, but an ontological realism. Epistemological realism argues that our representations and language are accurate mirrors of the world as it actually is, regardless of whether or not we exist. It seeks to distinguish between true representations and phantasms. Ontological realism, by contrast, is not a thesis about our knowledge of objects, but about the being of objects themselves, whether or not we exist to represent them. It is the thesis that the world is composed of objects, that these objects are varied and include entities as diverse as mind, language, cultural and social entities, and objects independent of humans such as galaxies, stones, quarks, tardigrades and so on. Above all, ontological realisms refuse to treat objects as constructions of humans. While it is true, I will argue, that all objects translate one another, the objects that are translated are irreducible to their translations. As we will see, ontological realism thoroughly refutes epistemological realism or what ordinarily goes by the pejorative title of “naïve realism”. Initially it might sound as if the distinction between ontological and epistemological realism is a difference that makes no difference but, as I hope to show, this distinction has far ranging consequences for how we pose a number of questions and theorize a variety of phenomena.

One of the problematic consequences that follows from the hegemony that epistemology currently enjoys in philosophy is that it condemns philosophy to a thoroughly anthropocentric reference. Because the ontological question of substance is elided into the epistemological question of our knowledge of substance, all discussions of substance necessarily contain a human reference. The subtext or fine print surrounding our discussions of substance always contain reference to an implicit “for-us”. This is true even of the anti-humanist structuralists and post-structuralists who purport to dispense with the subject in favor of various impersonal and anonymous social forces like language and structure that exceed the intentions of individuals. Here we still remain in the orbit of an anthropocentric universe insofar as society and culture are human phenomena, and all of being is subordinated to these forces. Being is thereby reduced to what being is for us.

By contrast, this book strives to think a subjectless object, or an object that is for-itself rather than an object that is an opposing pole before or in front of a subject. Put differently, this essay attempts to think an object for-itself that isn't an object for the gaze of a subject, representation, or a cultural discourse. This, in short, is what the democracy of objects means. The democracy of objects is not a political thesis to the effect that all objects ought to be treated equally or that all objects ought to participate in human affairs. The democracy of objects is the ontological thesis that all objects, as Ian Bogost has so nicely put it, equally exist while they do not exist equally. The claim that all objects equally exist is the claim that no object can be treated as constructed by another object. The claim that objects do not exist equally is the claim that objects contribute to collectives or assemblages to a greater and lesser degree. In short, no object such as the subject or culture is the ground of all others. As such, The Democracy of Objects attempts to think the being of objects unshackled from the gaze of humans in their being for-themselves.

Such a democracy, however, does not entail the exclusion of the human. Rather, what we get is a redrawing of distinctions and a decentering of the human. The point is not that we should think objects rather than humans. Such a formulation is based on the premise that humans constitute some special category that is other than objects, that objects are a pole opposed to humans, and therefore the formulation is based on the premise that objects are correlates or poles opposing or standing-before humans. No, within the framework of onticology—my name for the ontology that follows—there is only one type of being: objects. As a consequence, humans are not excluded, but are rather objects among the various types of objects that exist or populate the world, each with their own specific powers and capacities.

It is here that we encounter the redrawing of distinctions proposed by object-oriented philosophy and onticology. In his Laws of Form, George Spencer-Brown argued that in order to indicate anything we must first draw a distinction. Distinction, as it were, precedes indication. To indicate something is to interact with, represent, or point at something in the world (indication takes a variety of forms). Thus, for example, when I say the sun is shining, I have indicated a state-of-affairs, yet this indication is based on a prior distinction between, perhaps, darkness and light, gray days and sunny days, and so on. According to Spencer-Brown, every distinction contains a marked and an unmarked space.

The right-angle is what Spencer-Brown refers to as the mark of distinction. The marked space opens what can be indicated, whereas the unmarked space is everything else that is excluded. Thus, for example, I can draw a circle on a piece of paper (distinction), and can now indicate what is in that circle. Two key points follow from Spencer-Brown's calculus of distinctions. First, the unmarked space of a distinction is invisible to the person employing the distinction. While it is true that, in many instances, the boundary of a distinction can be crossed and the unmarked space can be indicated, in the use of a distinction the unmarked space of the distinction becomes a blind-spot for the system deploying the distinction. That which exists in the unmarked space of the distinction might as well not exist for the system using the distinction.

However, the unmarked space of the distinction is not the only blind-spot generated by the distinction. In addition to the unmarked space of a distinction, the distinction itself is a blind-spot. In the use of a distinction, the distinction itself becomes invisible insofar as one passes “through” the distinction to make indications. The situation here is analogous to watching a bright red cardinal on a tree through one's window. Here the window becomes invisible and all our attention is drawn to the cardinal. One can either use their distinctions or observe their distinctions, but never use their distinctions and observe their distinctions. By virtue of the withdrawal of distinctions from view in the course of using them, distinctions thus create a reality effect where properties of the indicated seem to belong to the indicated itself rather than being effects of the distinction. As a consequence, we do not realize that other distinctions are possible. The result is thus that we end up surreptitiously unifying the world under a particular set of distinctions, failing to recognize that very different sorts of indications are possible.

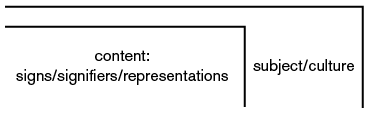

Within the marked space of its distinctions, much contemporary philosophy and theory places the subject or culture. As a consequence, objects fall into the unmarked space and come to be treated as what is other than the subject.

Here one need only think of Fichte for a formalization of this logic. Within any distinction there can also be sub-distinctions that render their own indications possible. In the case of the culturalist schema, the subject/culture distinction contains a sub-distinction marking content. The catch is that in treating the object as what is opposed to the subject or what is other than the subject, this frame of thought treats the object in terms of the subject. The object is here not an object, not an autonomous substance that exists in its own right, but rather a representation. As a consequence of this, all other entities in the world are treated only as vehicles for human contents, meanings, signs, or projections. By analogy, we can compare the culturalist structure of distinction with cinema. Here the object would be the smooth cinema screen, the projector would be the subject or culture, and the images would be contents or representations. Within this schema, the screen is treated as contributing little or nothing and all inquiry is focused on representations or contents. To be sure, the screen exists, but it is merely a vehicle for human and cultural representations.

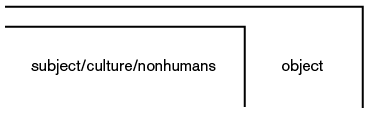

Onticology and object-oriented philosophy, by contrast, propose to place objects in the marked space of distinction.

It will be noted that when objects are placed in the marked space of distinction, the sub-distinction does not contract what can be indicated, but rather expands what can be indicated. Here subjects and culture are not excluded, but rather are treated as particular types of objects. Additionally, it now becomes possible to indicate nonhuman objects without treating them as vehicles for human contents. As a consequence, this operation is not a simple inversion of the culturalist schema. It is not a call to pay attention to objects rather than subjects or to treat subjects as what are opposed to objects, rather than treating objects as being opposed to subjects. Rather, just as objects were reduced to representations when the subject or culture occupied the marked space of distinction, just as objects were effectively transformed into the subject and content, the placement of objects in the marked space of distinction within the framework of ontology transforms the subject into one object among many others, undermining its privileged, central, or foundational place within philosophy and ontology. Subjects are objects among objects, rather than constant points of reference related to all other objects. As a consequence, we get the beginnings of what anti-humanism and post-humanism ought to be, insofar as these theoretical orientations are no longer the thesis that the world is constructed through anonymous and impersonal social forces as opposed to an individual subject. Rather, we get a variety of nonhuman actors unleashed in the world as autonomous actors in their own right, irreducible to representations and freed from any constant reference to the human where they are reduced to our representations.

Thus, rather than thinking being in terms of two incommensurable worlds, nature and culture, we instead get various collectives of objects. As Latour has compellingly argued, within the Modernist schema that drives both epistemological realism and epistemological anti-realism, the world is bifurcated into two distinct domains: culture and nature. [3] The domain of the subject and culture is treated as the world of freedom, meaning, signs, representations, language, power, and so on. The domain of nature is treated as being composed of matter governed by mechanistic causality. Implicit within forms of theory and philosophy that work with this bifurcated model is the axiom that the two worlds are to be kept entirely separate, such that there is to be no inmixing of their distinct properties. Thus, for example, a good deal of cultural theory only refers to objects as vehicles for signs or representations, ignoring any non-semiotic or non-representational differences nonhuman objects might contribute to collectives. Society is only to have social properties, and never any sorts of qualities that pertain to the nonhuman world.

It is my view that the culturalist and modernist form of distinction is disastrous for social and political analysis and sound epistemology. Insofar as the form of distinction implicit in the culturalist mode of distinction indicates content and relegates nonhuman objects to the unmarked space of the distinction, all sorts of factors become invisible that are pertinent to why collectives involving humans take the form they do. Signifiers, meanings, signs, discourses, norms, and narratives are made to do all the heavy lifting to explain why social organization takes the form it does. While there can be no doubt that all of these agencies play a significant role in the formation of collectives involving humans, this mode of distinction leads us to ignore the role of the nonhuman and asignifying in the form of technologies, weather patterns, resources, diseases, animals, natural disasters, the presence or absence of roads, the availability of water, animals, microbes, the presence or absence of electricity and high speed internet connections, modes of transportation, and so on. All of these things and many more besides play a crucial role in bringing humans together in particular ways and do so through contributing differences that while coming to be imbricated with signifying agencies, nonetheless are asignifying. An activist political theory that places all its apples in the basket of content is doomed to frustration insofar as it will continuously wonder why its critiques of ideology fail to produce their desired or intended social change. Moreover, in an age where we are faced with the looming threat of monumental climate change, it is irresponsible to draw our distinctions in such a way as to exclude nonhuman actors.

On the epistemological front, the subject/object distinction has the curious effect of leading the epistemologist to focus on propositions and representations alone, largely ignoring the role that practices and nonhuman actors play in knowledge-production. As a consequence, the central question becomes that of how and whether propositions correspond to reality. In the meantime, we ignore the laboratory setting, engagement with matters and instruments, and so on. It is as if experiment and the entities that populate the laboratory are treated as mere means to the end of knowledge such that they can be safely ignored as contributing nothing to propositional content, thereby playing no crucial role in the production of knowledge. Yet by ignoring the site, practices, and procedures by which knowledge is produced, the question of how propositions represent reality becomes thoroughly obscure because we are left without the means of discerning the birth of propositions and the common place where the world of the human and nonhuman meets.

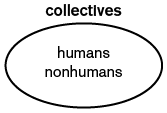

In shifting from a dual ontology based on the nature/culture split to collectives, onticology and object-oriented philosophy place all entities on equal ontological footing. Rather than two distinct ontological domains, the domain of the subject and the domain of the object, we instead get a single plane of being populated by a variety of different types of objects including humans and societies:

The concept of collectives does not approach being in terms of two separate domains, but rather as a single plane in which, to use Karen Barad's apt term, objects are entangled with one another. [4] In this regard, society and nature do not form two separate and entirely distinct domains that must never cross. Rather, collectives involving humans are always entangled with all sorts of nonhumans without which such collectives could not exist. To be sure, such collectives are populated by signs, signifiers, meanings, norms and a host of other sundry entities, but they are also populated by all sorts of asignifying entities such as animals, crops, weather events, geographies, rivers, microbes, technologies, and so on. Onticology and object-oriented ontology draw our attention to these entanglements by placing the human and nonhuman on equal footing.

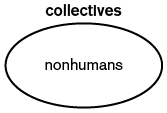

However, it would be a mistake to suppose that collectives necessarily involve humans. There are collectives that involve humans and other collectives of objects that have nothing to do with humans:

In short, not everything is related to the human, nor, as I will argue in what follows, is everything related to everything else. While we might be particularly interested in collectives involving humans because we happen to be human, from the standpoint of ontology we must avoid treating all collectives as involving the human.

From the foregoing it can be gathered that the ontology I am proposing is rather peculiar. Rather than treating objects as entities opposed to a subject, I treat all entities, including subjects, as objects. Moreover, in order to overcome the dual world hypothesis of Modernity, I argue that it is necessary to staunchly defend the autonomy of objects or substances, refusing any reduction of objects to their relations, whether these relations be relations to humans or other objects. In my view, the root of the Modernist schema arises from relationism. If we are to escape the aporia that beset the Modernist schema this, above all, requires us to overcome relationism or the thesis that objects are constituted by their relations. Accordingly, following the ground-breaking work of Graham Harman's object-oriented philosophy, I argue that objects are withdrawn from all relation. The consequences of this strange thesis are, I believe, profound. On the one hand, in arguing that objects are withdrawn from their relations, we are able to preserve the autonomy and irreducibility of substance, thereby sidestepping the endless, and at this point rather stale, debate between the epistemological realists and anti-realists. On the other hand, where the anti-realists have obsessively focused on a single gap between humans and objects, endlessly revolving around the manner in which objects are inaccessible to representation, object-oriented philosophy allows us to pluralize this gap, treating it not as a unique or privileged peculiarity of humans, but as true of all relations between objects whether they involve humans or not. In short, the difference between humans and other objects is not a difference in kind, but a difference in degree. Put differently, all objects translate one another. Translation is not unique to how the mind relates to the world. And as a consequence of this, no object has direct access to any other object.

Onticology and object-oriented philosophy thus find themselves in a strange position with respect to speculative realism. Speculative realism is a loosely affiliated philosophical movement that arose out of a Goldsmith's College conference organized by Alberto Toscano in 2007. While the participants at this event—Ray Brassier, Iain Hamilton Grant, Graham Harman, and Quentin Meillassoux—share vastly different philosophical positions, they are all united in defending a variant of realism and in rejecting anti-realism or what they call “correlationism”. With the other speculative realists, onticology and object-oriented philosophy defend a realist ontology that refuses to treat objects as constructions or mere correlates of mind, subject, culture, or language. However, with the anti-realists, onticology and object-oriented philosophy argue that objects have no direct access to one another and that each object translates other objects with which it enters into non-relational relations. Object-oriented philosophy and onticology thus reject the epistemological realism of other realist philosophies, taking leave of the project of policing representations and demystifying critique. The difference is that where the anti-realists focus on a single gap between humans and objects, object-oriented philosophy and onticology treat this gap as a ubiquitous feature of all beings. One of the great strengths of object-oriented philosophy and onticology is thus, I believe, that it can integrate a number of the findings of anti-realist philosophy, and continental social and political theory, without falling into the deadlocks that currently plague anti-realist strains of thought.

For those not familiar with the basic claims of object-oriented philosophy and onticology, a list of object-oriented heroes might prove helpful for gaining orientation within onticology. Among the heroes of onticology are Graham Harman, Bruno Latour, Isabelle Stengers, Timothy Morton, Ian Bogost, Niklas Luhmann, Jane Bennett, Manuel DeLanda, Marshall McLuhan, Friedrich Kittler, Karen Barad, John Protevi, Walter Ong, Deleuze and Guattari, developmental systems theorists such as Richard Lewontin and Susan Oyama, Alfred North Whitehead, Donna Haraway, Roy Bhaskar, Katherine Hayles, and a host of others. Some of these thinkers appear more than others in the pages that follow, and others appear scarcely or not at all, but all have deeply influenced my thought. The thread that runs throughout the work of these thinkers is a profound decentering of the human and the subject that nonetheless makes room for the human, representation, and content, and an accompanying attentiveness to all sorts of nonhuman objects or actors coupled with a refusal to reduce these agencies to vehicles of content and signs. In developing my argument, I have proceeded as a bricoleur, freely drawing from a variety of disciplines and thinkers whose works are not necessarily consistent with one another. Of the bricoleur, Lévi-Strauss writes that,

For readers startled by some of the thinkers and lines of thought I forge together in the pages that follow, it is worthwhile to recall that this is the work of a bricoleur and that it very much reflects the idiosyncrasies of my own intellectual background and development. For example, Lacan makes a number of appearances in the pages that follow and this reflects my time in a previous incarnation as a practicing psychoanalyst. As I argue in what follows, every object is a crowd and this is above all true of books. Where the materials out of which a book is constructed might themselves be heterogeneous, what is important is not whether these other materials are in themselves consistent with one another, but rather whether the product formed from these parts manages to attain some degree of consistency in the formation of a new object. Readers, for example, might be surprised to discover Harman's object-oriented ontology, the constructivism of Niklas Luhmann's autopoietic social theory, Deleuze and Guattari's ontology of the virtual, and the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan rubbing elbows with one another. Standing alone, these various theories are opposed on a number of fronts. However, the work of a bricoleur consists in forging together heterogeneous materials so as to produce something capable of standing on its own. I hope that I've done so, but I make no claim that this is the only way that object-oriented ontology can be formulated, nor am I particularly interested in policing others with a theory of reality.

It is unlikely that object-oriented ontologists are going to persuade epistemological realists or anti-realists that they have found a way of surmounting the epistemological problems that arise out of the two-world model of being any time soon. Quoting Max Planck, Marshall and Eric McLuhan write, “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it”. [6] This appears to be how it is in philosophy as well. New innovations in philosophy do not so much refute their opponents as simply cease being preoccupied by certain questions and problems. In many respects, object-oriented ontology, following the advice of Richard Rorty, simply tries to step out of the debate altogether. Object-oriented ontologists have grown weary of a debate that has gone on for over two centuries, believe that the possible variations of these positions have exhausted themselves, and want to move on to talking about other things. If this is not good enough for the epistemology police, we are more than happy to confess our guilt and embrace our alleged lack of rigor and continue in harboring our illusions that we can speak of a reality independent of humans. However, such a move of simply moving on is not unheard of in philosophy. No one has yet refuted the solipsist, nor the Berkeleyian subjective idealist, yet neither solipsism nor the extremes of Berkeleyian idealism have ever been central and ongoing debates in philosophy. Philosophers largely just ignore these positions or use them as cautionary examples to be avoided. Why not the same in the endless debates over access?

Nonetheless, in the pages that follow I do try to formulate arguments that epistemically ground the ontological realism that I defend. The first chapter outlines the grounds for ontological realism, drawing heavily on the transcendental realism developed by Roy Bhaskar. The basic thrust of this argument is transcendental in character and argues that the world must be structured in a particular way for experimental activity to be intelligible and possible. Bhaskar's articulation of these transcendental, ontological conditions also provides me with the means of outlining the basic structure of objects, the relation between substance and qualities, the independence of objects from their relations, and the withdrawn structure of objects. Here I also uncover the root assumption that leads to the endless debates of anti-realism and epistemological realism.

Having outlined the basic structure of objects, the second chapter explores Aristotle's concept of substance, carefully distinguishing it from that which is simple or indivisible, and outlining the relationship between substance and qualities. Here a problem emerges. On the one hand, substance is necessarily distinct from its qualities in that qualities can change, yet substance persists. On the other hand, the subtraction of all qualities from a substance seems to lead us to a bare substratum or a completely featureless substance that would therefore be identical to all other substances or objects. Additionally, while substance is the very being of an object, its individuality or singularity, substances only ever manifest themselves through their qualities. With respect to this third problem, I argue that the very being of substance consists in simultaneously withdrawing and in self-othering. The structure of substance is such that it others itself in its qualities. However, if such an account of substance is to be successful, it is necessary to provide an account of withdrawn substance that is structured without being qualitative. How are we to think such a non-qualitative structure?

Having encountered the problem of non-qualitative structure, the third chapter turns to Deleuze's ontology and the distinction between the virtual and the actual. There I critique Deleuze's tendency to treat the virtual as something other than the individual, arguing that the individual precedes the virtual such that virtuality is always the virtuality of a substance. I refer to this as “virtual proper being” and treat it as the powers or capacities of an entity. Deleuze's concept of the virtual provides us with the means of thinking substance as structured without being qualitative. I refer to the qualities produced out of virtual structure as “local manifestations” and treat them as events, actions, or activities on the part of objects.

If objects are withdrawn from one another, then how do they relate? This is the problem of what Harman refers to as “vicarious causation”. How do objects relate to one another when they are necessarily independent of all their relations? Chapter four picks up with this question and turns to the autopoietic theory of Niklas Luhmann to provide an account of interactions between withdrawn objects. There I argue that all objects are operationally closed such that they constitute their own relation and openness to their environment. Relations between objects are accounted for by the manner in which objects transform perturbations from other objects into information or events that select system-states. These information-events or events that select system-states are, in their turn, among the agencies that preside over the production of local manifestations in objects.

Chapter five turns to questions of constraint, relations between parts and wholes, and time and entropy. If objects are withdrawn from one another, how is it that they can constrain one another? Drawing on the resources of developmental systems theory in biology, I attempt to provide an account of how an object can simultaneously construct its environment and be constrained by its environment, leading local manifestations to take particular forms. The section on mereology develops an account of relations between larger-scale objects and smaller-scale objects, defending the autonomy of larger-scale objects from the smaller-scale objects out of which they are built and the autonomy of the smaller-scale objects that compose the larger-scale object. Here I argue that a number of problems that have haunted contemporary social and political theory arise from a failure to be properly attentive to these strange mereological relations. The chapter closes with a discussion of temporalized structure, the relation of objects to time and space, and how objects stave off entropy or destruction across time.

Finally, chapter six outlines the four theses of flat ontology advocated by onticology. The first of these theses is that all objects are withdrawn, such that there are no objects characterized by full presence or actuality. Withdrawal is not an accidental feature of objects arising from our lack of direct access to them, but is a constitutive feature of all objects regardless of whether they relate to other objects. To develop this thesis I draw on Lacan's graphs of sexuation, treating them not as accounts of sex, but rather as two very different ontological discourses: ontologies of immanence and withdrawal and ontologies of presence and transcendence. The second thesis of flat ontology is that the world does not exist. Here I argue that there is no “super-object”, Whole, or totality that would gather all objects together in a harmonious unity. The third thesis is that humans occupy no privileged place within being and that between the human/object relation and any other object/object relation there is only a difference in degree, not kind. Finally, the fourth thesis is that objects of all sorts and at all scales are on equal ontological footing, such that subjects, groups, fictions, technologies, institutions, etc., are every bit as real as quarks, planets, trees, and tardigrades. The fourth thesis of flat ontology invites us to think in terms of collectives and entanglements between a variety of different types of actors, at a variety of different temporal and spatial scales, rather than focusing exclusively on the gap between humans and objects.

In the pages that follow I have, above all, pursued three aims. First, I have sought to provide an ontological framework capable of providing a synthesis of two very different research programs. Within cultural studies there is a sharp divide between those forms of inquiry that focus on signification and those forms of inquiry that focus on the material in the form of technologies, media, and material conditions. Likewise, the broader and dominant tendency of the humanities has been to focus on content, excluding the material. I have sought an ontological framework capable of integrating these diverse tendencies. However, second, such an integration requires an avoidance of reductivism. To the same degree that natural entities ought not be reduced to cultural constructions, social, semiotic, and cultural entities ought not be reduced to natural entities. This requires us to shift from thinking in terms of reduction or grounding one entity in another, to thinking in terms of entanglements. Entanglements allow us to maintain the irreducibility, heterogeneity, and autonomy of various types of entities while investigating how they influence one another. Finally, third, I have above all sought to write a book that is both accessible to a wide audience and that can be put to work by others in a wide variety of disciplines and practices, generating new questions and projects. I hope I have been somewhat successful in accomplishing these aims.

Notes

-

Samuel Alexander, Space, Time and Deity vol. I

(London: Adamant Media Corporation, 2007) p. 7.

-

Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (New York: Houghton and

Mifflin, 2008).

-

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, trans. Catherine

Porter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993

-

Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and

the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke University Press,

2007).

-

Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1966) pp. 17–18.

-

Marshall and Eric McLuhan, Laws of Media: The New Science

(Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988) p. 42.