5.3. Temporalized Structure and Entropy

As we discovered in the last section, every object is threatened from within and without by entropy such that it faces the question of how to perpetuate its existence across time. Entropy refers to the degree of disorder within a system. Suppose you have a tightly closed glass box and somehow introduce a gas into it. During the initial phases following the introduction of the gas into the system, the gas will be characterized by a high degree of order or a low degree of entropy. This is so because the particles of gas will be localized in one or the other region of the box. However, as time passes, the degree of disorder and entropy within the system will increase as the gas becomes evenly distributed throughout the box. In this respect, entropy is a measure of probability. If the earlier phases of the gas distribution indicate a lower degree of entropy than the later stages, then this is because in the earlier phases there is a lower degree of probability that the gas will be localized in any one place in the box. As time passes, the probability of finding gas particles located evenly throughout the box increases and we subsequently conclude that the degree of entropy has increased.

In many respects, the real miracle is not that change takes place, but rather that change is not more frequent. This is especially mysterious in the case of higher-order or higher-scale systems or objects such as social systems. How is it that they maintain their endo-consistency or organization across time, such that they don't disintegrate into a high degree of entropy? Put differently, why do such objects not dissolve as objects? In what follows, I focus on Luhmann's analysis of the relationship between structure, complexity, entropy, and time as it pertains to biological, psychic, and social objects. I leave the analysis of structure and entropy as it functions in nonliving objects to others, noting that when suitably modified by an object-oriented framework, the work of DeLanda and Massumi is particularly promising in this connection.

There are a number of reasons that Luhmann's conception of structure is particularly promising. First, the tendency of structuralism was to fall into a sort of structural imperialism arising from a failure to note the manner in which systems distinguish themselves from their environment or are withdrawn. Structure became a sort of net thrown over the entire world without remainder or outside. To be sure, structuralists recognized that something other than structure exists, yet were unable to articulate what this might be because of the manner in which we are always-already situated within structure such that everything we might encounter is overdetermined by structure. This schema posed very difficult questions for structuralist thought with respect to the question of how change takes place. The structuralists recognized that structures are organized synchronically and evolve diachronically, yet were left without the means of accounting for just how this diachronic evolution takes place because their doctrine of internal relations, coupled with their formalism, prevented them from appealing to any outside as a mechanism of change. As a consequence, the development or evolution of structure became thoroughly mysterious.

I take it that I have already shown how, in the first chapter, we can speak of objects independent of us despite the fact that all objects are withdrawn. One major advancement introduced by Luhmann's concept of structure is to mark both the boundary of structure and the conditions under which structures can change or evolve. Closely connected to this is a pluralization of structure with respect to different systems, allowing us to conceptualize a variety of different structures embedded and entangled with one another, yet also operationally closed to one another, such that each one “comprehends” the entirety of the world in terms of its own organization. In this respect, Luhmann is able to account simultaneously for the particularity or finitude of objects and their curious universality. As Luhmann writes in The Reality of the Mass Media,

In other words, each object or system is universal in the sense that it is able to comprehend the rest of the world in terms of its own distinctions. Nonetheless, each system is particular precisely because it relates to its environment or the rest of the world in terms of its own specific distinctions.

The rise of structuralist thought marked a growing awareness of this paradoxical simultaneity of universality and specificity. Replacing the universal Kantian transcendental subject, the structuralists recognized the contingency and plurality of different structures and how they relate to the environment through their own distinctions. Implicitly they thus recognized the manner in which objects are withdrawn from other objects. At the methodological level, they implicitly practiced second-order observation, observing how observers observe, by observing the manner in which other social systems or objects relate to the world. Yet this line of inquiry, as promising as it was, was itself under-theorized. On the one hand, having made the monumental discovery that there are other objects at a larger scale than human beings or subjects such as social systems, they made the move of treating lower scale objects such as humans as mere effects of structure so as to protect their important discovery and prevent all subjectivist or humanist attempts to ground these larger scale objects in the cognitive and affective capacities of psychic systems. Rather than adopting an ontological mereology of objects at a variety of scales and durations that are all operationally closed and that relate to each other only selectively, they instead attempted to banish these other lower-scale objects altogether. Yet, in making such a move, they swept the ground out from beneath themselves as they could no longer account for how their own discussion of structure was anything other than yet another formation being produced by structure itself.

On the other hand, having recognized system-specific universality in the plurality of structures they had uncovered in the domain of culture and language, they nonetheless tended to fail in properly theorizing the conditions under which they could make these claims. In other words, in their structuralist imperialism of treating structure as a net thrown over the entire world, they undermined the possibility of accounting for how second-order observation of other structures might be possible. In part, this problem emerged as a result of failing to properly mark or identify the limits of structure. A similar problem has more recently emerged in the radical constructivism of Maturana's autopoietic theory.

Among his major contributions to our understanding of structure lies Luhmann's treatment of structure in terms of the distinction between system and environment and the temporal problem of how structures reproduce themselves across time. It will be recalled that the environment is always more complex than any structure or environment. There is never a point-for-point correspondence between system and environment. Were there such a correspondence, system would cease to exist. As a consequence, objects only maintain selective relations to their environment, and this entails that the relations a system maintains to its environment always involve contingency and risk with respect to the ongoing autopoiesis or existence of the object. As Graham Harman puts it, every object caricatures other objects when relating to them. Moreover, objects have an internal complexity such that every element is not related to every other element, but rather elements are only related in specific ways. Not only do the ongoing operations or events that take place within an object risk falling into entropy, but each object is threatened by disintegration from events in its internal and external environment. Structure names the mechanism or organization through which a system or object both makes use of entropy to continue its existence and resists falling into entropy. As Luhmann writes,

The advantage of treating structure in terms of the system/environment distinction is that it allows us to think the manner in which structure is open to the world, thereby providing structure with events from the outside that play a role in how structure evolves or develops. Likewise, by treating structure in terms of entropy and complexity, we can see how structure is related to questions of how an object reproduces itself across time.

It is sometimes contended that structure consists of relations between elements. Luhmann rejects this thesis on the grounds that it is too broad and indeterminate. While it is indeed the case that within any structure elements are related to one another, these relations are of a specific kind. On the one hand, while it is the case that one and the same structure can be embodied in a variety of elements, it doesn't follow from this that a structure can be embodied in any element. This feature of multiple realizability is crucial to understanding structure and objects, for it is almost always the case that the elements that realize a structure are destroyed or pass away, while the structure remains and persists. For example, citizens are born and die in the United States, and offices are occupied by a variety of different politicians. It is thus not the parts that make an entity an entity precisely because these parts can change. However, it would be a mistake to conclude from this that structures can exist without their elements. Objects can be destroyed through their parts insofar as a point is reached where the endo-structure of an object can no longer embody or sustain itself. It is precisely because the elements that realize structure pass away that systems or objects face the question of how to perpetuate themselves across time. In the case of autopoietic objects, the object faces the question of how to produce new events or elements to maintain itself across time.

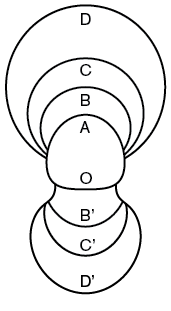

In short, each system or object must reproduce itself across time. In the absence of a reproduction of elements and therefore of relations, the object dissolves or falls apart. In this respect, we can see just how dynamic objects are. Objects are not brute clods that simply sit there unchanging until provoked, but perpetually reproduce themselves in the order of time. This structure of reproduction can be represented in terms of Bergson's diagram of attention and memory as presented in Matter and Memory.[255]

Bergson uses this diagram to outline the role of memory in the process of perception, yet it works equally well for thinking the reproduction of objects across time. In Bergson's schema, each moment of perception is overlaid by a memory image trailing off into the remote past. Bergson describes this as a “circuit” of perception and memory, where the two come to be ever more deeply intertwined. In the case of perception, the result is that each perception becomes increasingly overlaid by memory. Bergson's circuit of perception and memory is particularly illustrative of the dynamics of autopoietic objects in the order of time. ABCD refers to the subsequent reproduction of the object in the course of unfolding in time or in moving towards the future. By contrast, A'B'C'D' refers to the memory produced by the autopoietic object that can, in its turn, be reactualized in the present in a variety of ways. The object uses each prior phase, as well as stimulations from its environment, to reproduce itself across time. Similarly, in autopoietic objects, memory can be used to actualize new states in the present. As a consequence, objects are temporally elongated, tracing a path throughout time through their acts.

Why, then, if objects must reproduce themselves from moment to moment, do I not follow Whitehead in arguing that being, at its most basic level, is composed of “actual occasions” and that objects are but “societies of actual occasions”? Whitehead's actual occasions are instantaneous events that cease to exist the very moment that they come into existence. They are the true atoms of being, with the important caveat that these atoms are not enduring entities, like Lucretius's atoms, but events that flicker in and out of existence like the flickering of fireflies. As a consequence, from a Whiteheadian perspective, objects are a sort of illusion in the sense that they are not the true units of beings, but are rather multiple-compositions or societies of actual occasions that are continually coming into existence and passing out of existence. In this respect, Bergson's circuit of the object, coupled with Luhmann's thesis that objects must perpetually reproduce themselves in the order of time, would seem to be a mirror image of Whitehead's metaphysical thesis.

However, to treat actual occasions or instantaneous time-slices as the atoms or true units of being is to confuse the being of objects with their parts. An object is not its parts, elements, or the events that take place within it—though all of these are indeed indispensable—but is rather an organization or structure that persists across time. This brings us to Luhmann's second reason as to why structure cannot be identified with relations among elements simpliciter. As Luhmann remarks,

From this Luhmann concludes that “structure, whatever else it may be, consists in how permissible relations are constrained within the system”.[257] What Whitehead's account of objects as societies of actual occasions misses is that this organization, this constraint on permissible relations among elements, is not itself of the order of an actual occasion but is rather that which persists or endures across the existence of actual occasions. To be sure, these structures exist only in and through actual occasions, but this does not change the fact that these structures are irreducible to actual occasions for, without structure, there could be no regulation of how events are constrained and produced in the ongoing existence of the object.

A system in which all elements related to one another would be a system characterized by absolute entropy and would thus be no system at all because it would be unable to distinguish itself from its environment. There are thus three problems that beset each system and to which structure responds. First, there is the question of how events are to be constrained and selected within a system. For example, were all possible memories, thoughts, and imaginings to suddenly flood the mind, the mind would immediately collapse into absolute entropy, falling into an autistic jumble preventing any action or attention. Within a psychic system, there must be selectivity as to what events take place within the psychic system and how these events are linked to one another.

Second, and similarly, there must be selectivity or constraint with respect to the events that a system is open to from the world or its environment. Take the example of an object like a conversation at a cafe. If such a conversation is to be possible, its relationship to its environment must be highly constrained, remaining open only to certain events within the coffee shop. Of course, this openness to the environment can shift with changing events within the system such that the system becomes open to events that it was previously closed to, but the point is that at any point in time the system only maintains selective relations to its environment. Within the cafe, all sorts of conversations are taking place, people are bustling about, waiters and waitresses are serving various customers, cappuccino machines are hissing their songs, music is playing, people are walking back and forth on the sidewalk, and cars are honking and screeching outside. Were the conversation as a system or object to share a one-to-one correspondence to all these events in the environment, the conversation would be impossible and would again fall into a maximum state of entropy. As a consequence, the conversation can only be selectively open to events in its environment, constituting itself as an object or system through a system/environment distinction that both constitutes the conversation as an object distinct from its environment and that institutes selective relations to the environment, allowing certain events occurring within the environment to perturb the system constituted by the conversation. Two young women heatedly discussing Sartre's Being and Nothingness and whether he stole his ideas from Simone de Beauvoir pause suddenly when an impending blizzard is announced over the radio. This event functions like a switch. Suddenly the conversation changes direction and the women begin discussing whether they should leave to beat the weather, only to turn back to Sartre's discussions of facticity and how they constrain choice. This event perturbs the conversation in a particular way, leading it to drift in another direction, yet what is more remarkable is all the other events in the environment that fall into the unmarked space of the distinctions regulating the conversation's relationship to its environment, becoming all but invisible. Only certain events from the environment are capable of influencing the local manifestations the conversation takes.

Finally, each system faces the question of how to produce subsequent events so as to continue its existence across time. Luhmann remarks that “one must radically relate the concept of event [...] to what is momentary and immediately passes away”.[258] Because events are momentary and fleeting, and because structure can only exist so long as it is embodied in elements, each system or object faces the question of how to pass from one event to another so as to perpetuate its existence. As Luhmann observes, “we will constrain the concept of structure in another way: not as a special type of stability but by its function of enabling the autopoietic reproduction of the system from one event to the next”.[259] In the space of a conversation, it is necessary to find something else to say if the conversation is to continue. The production of events can take place either through the internal domain of the system itself, as in those instances where one utterance in a conversation leads to another utterance or one secretion of a cell initiates processes in another cell in a body, or through perturbations coming from the environment.

Because objects face the question of how to get from one moment to the next, they are condemned to change and their identity is a dynamic identity that perpetually reproduces itself across time. As Luhmann argues,

In the case of autopoietic objects such as organisms, tornadoes, social systems, psychic systems, and conversations, events taking place in the present modify the substance’s relationship to the past as well as the future. This is especially the case with respect to the role played by events that issue from the environment. Upon reading a book once, rereading the book produces a different impression of the book as a result of both how the first reading reconfigured my prior thoughts about the world and other texts and as a result of how the opening pages of the book now resonate differently as a result of my anticipation of what is coming. As a consequence, objects develop and evolve.

Information plays a particularly important role in the development and evolution of structures. Because structures operate within the framework of system/environment distinctions, they are selectively open to their environment and can therefore evolve and develop as a result of that openness to their environment. Objects constrain the sort of events to which they're open from their environment through their distinctions or organization. In the case of autopoietic objects, this entails that structures are anticipatory of what the future will bring. When events issue from the environment, information-events are produced selecting system-states within the system. This leads to the production of further events within the system, unfolding within a particular order and structured in a particular way. This can have the effect of reinforcing and intensifying certain developmental vectors within the object.

However, because structures are anticipatory, they can also undergo disappointment when events anticipated from the environment fail to materialize. However, it would be a mistake to conclude that the disappointment of an anticipation entails the absence of information. As we have seen, in more “advanced” objects, the absence of an event can itself function as information. In Sartre's famous example in Being and Nothingness, he walks into a cafe and discovers that his friend Pierre is not there.[261] Far from being an absence of information, the non-event of Pierre's appearance creates an event, information, that selects subsequent system-states. Depending on the magnitude of the disappointment, such information events can have the effect of propelling systems capable of self-reflexivity to revise their distinctions, modifying their system structure and developing new forms of openness to the world while foreclosing other forms of openness. Similarly, in the case of autopoietic objects or systems not capable of self-reflexivity, such disappointments can play a key role in natural selection, leading to the death of certain substances reliant on particular forms of perturbation to continue their existence and paving the way for other organisms to more effectively reproduce themselves. This can occur when massive environmental changes take place. Indeed, certain organisms unwittingly produce their own demise as in the case of pre-historic microorganisms that required carbon dioxide to continue their autopoiesis or self-reproduction and that produced oxygen as a bi-product of this process. One result of this process was that they eventually saturated their environment with oxygen, contributing to the construction of new niches in which other organisms could emerge and undermining the niche upon which they relied for their continued existence.

From the foregoing, we can thus see why selection, constraint, distinction, and organization involve risk at the level of structure. Structure is contingent in the sense that both the manner in which elements are related and the openness to events within the environment could always be otherwise. Insofar as structure is a strategy for staving off entropy so as to reproduce system-organization across time, the contingency of selection and constraint carries with it the risk of dissolution in those instances where the selections opening the object to the environment anticipate perturbations or irritations that fail to reliably appear. In these instances, we encounter less than fortunate local manifestations or death. Here death can take one of two forms. On the one hand, death can take the form of a substance continuing to exist but becoming incapable of producing certain local manifestations such as movement, affect, and cognition. On the other hand, death can take the form of absolute death, where entropy completely sets in and the substance is utterly destroyed such that it is no longer able to enlist other objects in maintaining its own organization and the other objects of which the entity was once composed now go their separate ways autonomously, enjoying their existence elsewhere. The first death generally leads to the second eventually.

The risk of selectivity and constraint can be seen with particular clarity with respect to the issue of climate change. At present, the world's various social systems and subsystems lack sufficient capacities for resonance to register the importance of changes taking place in the climate. To be sure, much of the world's various social systems are aware that climate change is taking place and that this will potentially have a massive impact on whether or not these social systems are able to sustain themselves. However, despite this knowledge, we don't see social systems making the sorts of changes necessary to avoid this destruction. Why is this? A good deal of the problem has to do with the nature of resonance between various subsystems within the social system and between the various social systems and psychic systems. We can only learn of climate change through the scientific system and the media system because the changes produced by climate change are so diffuse and spread out that they can only be observed through very specific techniques. At the level of the other social systems and psychic systems, this generates doubt in the science system as the environments of these other social systems and psychic systems do not register any significant differences. Like two shades of red that are extremely close to one another, we see the climate as largely unchanged. The media system, in its turn, creates constant noise around the issue, endlessly parading experts before the viewing audience that claim that there is a lot of dispute surrounding whether or not anthropogenic climate change is taking place and who suggest it is based on junk science. Insofar as the media system is selectively open to its environment in terms of controversy so as to maximize its possibility of new reporting on a daily basis, it generates the impression in psychic systems that there is broad disagreement regarding these issues when, in fact, it is a minority of scientists, often funded by energy companies, who hold such views.

The more significant problem emerges with respect to resonance between the science system, the political system, and the economic system. The code according to which the economic system functions is the profit/no-profit code. In other words, the economic system encounters its environment in terms of whether or not it is capable of producing profit. As a consequence, the economic system is largely blind to the science system unless the findings of the science system create the opportunity for producing profit. Initially, it seems as if progress is being made in this regard as many businesses are adopting a “green orientation” that advertises an ecologically friendly orientation. However, the lion's share of our ecological problems issues not from whether we're using energy efficient light bulbs, but from farming practices (it's a dirty secret that livestock methane contributes more to climate change than the use of fossil fuels), industry, shipping, and the sort of energy we use. The sorts of changes required in these areas immediately fall into the “no-profit” side of the codes deployed by the economic system.

The political system, in its turn, finds itself entangled with the regimes of attraction governing the lives of psychic systems as well as the economic system. The code according to which the political system functions is that of power/no-power. In concrete terms, this code revolves around questions and issues of re-election. Many of the changes required to mitigate the effects of climate change would prove to be a significant hardship on lives of citizens, as it would require major changes in the regimes of attraction upon which they rely for their existence. This is especially the case in countries with developing economies where many are just trying to find a way to feed their families from day to day. While many might be abstractly supportive of taking action to mitigate the coming climate crisis, when concrete proposals are made, many of the suggested changes are deeply unpopular because these things would significantly impact how people live their lives (imagine how Americans would respond to being told to cut down on their meat consumption!) and might lead to the loss of jobs. This, in turn, translates into whether or not politicians get votes and get re-elected. As a consequence, it is likely that a Faustian bargain is made where the politician who is ecologically aware tells himself that at least he is making incremental change.

Nonetheless, it seems that a lot could be done by more heavily regulating the shipping industry, encouraging the trucking industry, for example, to switch over to alternative fuels, giving large tax breaks to families and individuals that drive hybrid cars, use solar panels, increase their energy efficiency, making the use of school buses and trains a patriotic action for high school students, and providing government subsidies to developing countries that provide and develop environmentally friendly industries for their citizens, and so on. However, here the political system encounters another entanglement with industry and business that makes such actions less than appealing from a political perspective. These changes all imply major economic hardship for a variety of businesses and industries that make massive amounts of money from their practices. In the United States at least, the 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission opened the gates for corporations to use unlimited funds for political purposes. This entails that every U.S. politician must now think twice before proposing policy changes as they now face massive advertising campaigns—always conducted behind “front groups” implying that they're the work of average Americans and grass root activists—targeting the possibility of the politician's re-election.

The point of this rather pessimistic analysis of resonance within social systems with respect to issues of climate change is to underline the manner in which the constraints and selections governing openness to the environment always involve risk. Within our current social system, the distinctions governing resonance between the various social subsystems, psychic systems, and the broader environment have generated a quagmire that renders responsiveness to climate change very difficult. The forms of resonance that do exist, in their turn, create the very real possibility that these social systems will themselves collapse as a result of changes in their environments that abolish sources of perturbation upon which they depend. As climate change and population growth intensifies, it is very likely that there will be famines as a result of changes in the climate that destroy farming and water resources. This will generate a variety of social crises that will reverberate throughout all the different social subsystems.

The question of how certain forms of system resonance can be diminished and how other forms of resonance can be enhanced thereby becomes a key question for activists concerned with issues of climate change. In his book, Collapse, Jared Diamond notes that one reason Dutch citizens, politicians, and businesses seem to be more eco-friendly is not because they are more enlightened, but because much of their landmass is below sea-level, rendering climate change in the form of rising sea levels a potential threat to the majority of the population.[262] Likewise, Diamond notes how foreign logging companies depleted the rain forests of the Malay Penninsula, Borneo, the Solomon Islands, Sumatra, and the Philippines by logging these lands as quickly as possible once they were leased to them by the local countries and then declaring bankruptcy rather than replanting as it was more beneficial financially to do so. The citizens of these areas were then left to endure the ecological consequences of these practices, losing their own sources of food and industry.[263] One lesson of these contrasting examples seems to be that resonance is enhanced when a system or object has a direct stake in the long-term preservation of elements of the local environment or climate. Yet how such a suture to local climate is to be produced in various industries is a very difficult question.

Returning to some themes from the last section pertaining to mereology, we can also discern that a number of objects have some very peculiar properties with respect to space and time. It is fairly common to argue that objects are individuated by occupying a particular position in space and at a particular time. This, for example, was Locke's position. However, if it is true that it is the organization or structure, not the parts, that determine whether or not something is an object, it follows that objects can be discontinuous across time and can be vastly spread out across space. A conversation, for example, can cease and be resumed at a later point. Here the conversation falls out of existence for a time, it ceases to manifest itself locally, and comes back into existence at a later point in time. A variety of objects have this strange sort of temporal structure. An Alcoholics Anonymous group, for example, might only meet once or twice a week, thereby flickering in and out of existence. A number of groups and institutions only meet intermittently.

Not only do we encounter this strange temporality where objects can flit in and out of existence while remaining the same object, but there are also a variety of different temporal scales characteristic of different objects that are oddly simultaneous with one another yet working at very different temporal levels. It takes the sun, for example, 225 million years to make one rotation around the Milky Way. The Milky Way is one object, characterized by its own temporal duration, whereas the solar system is yet another object. Here we encounter one temporal duration embedded in another temporal duration, with very different cycles unfolding in each object. Similarly, societies, climates, and ecosystems each have their own heterogeneous durations, moving at different rates and characterized by their own unique organizations. In this regard, there's a very real sense in which duration is always system-specific such that each object is characterized by its own duration and relates to other durations in terms of its own. Different social groups, for example, exist in their own “plane of history”, as can be observed with the old university professor who hasn't kept up with his reading and continues to fight philosophical wars that are decades past, or the Amish who live in a very different temporal frame both with respect to the structuration of their daily life and their relation to the broader social system in which they're embedded. The temporal rhythms of an organism are different from those of a population of organisms, and these, in their turn, are different from the temporal rhythms of an entire ecosystem. Between all these different temporalities are different forms of resonance, as well as different possibilities of conflict.

Similar features characterize the mereology of objects in space. Blog discussions involve participants located all over the world, integrating internet servers, various blogs, and participants so as to produce an evolving and developing object of its own. Increasingly a number of people work from home, yet various businesses still exist as entities in their own right. More recently, there's been a trend towards university courses being offered online, allowing students to enroll in courses at a specific university or college from all over the country and world. Indeed, a friend of mine makes his living teaching online courses “in” the United States from Israel. Currently, there are massive radio telescope arrays that span entire continents, drawing on many smaller radio telescopes to plumb the depths of outer space and using thousands of home computers volunteered by average citizens to increase their ability to compute the huge amounts of data they receive. And, were this not astonishing enough, the observations of these entities are not observations of entities existing in the present, but in the remote past!

At the level of object-oriented and onticological mereology, we cannot work from the premise that location in time and space is sufficient to individuate an object, nor that objects exist only at a particular scale such as the mid-range objects that tend to populate the world of our daily existence. Rather, entities exist at a range of different scales, from the unimaginably small to the unimaginably large, each characterized by their own duration and spatiality. Here a tremendous amount of work remains to be done in thinking these spatial and temporal structures. In my view, onticology and object-oriented philosophy have opened a vast and rich domain for thinking these strange structures of space and time. What is important, however, is the recognition that the substantiality of objects lies not in their parts, but in their structure or organization, and that objects are not brute clods that merely sit there, contemplating their self-perfection like Aristotle's Unmoved Mover, but that they are dynamic and evolving as a consequence of their own internal dynamics and interfaces with their environment.

Notes

-

Niklas Luhmann, The Reality of the Mass Media, trans.

Kathleen Cross (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000) p. 23.

-

Luhmann, Social Systems, p. 282.

-

Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory, p. 105.

-

Luhmann, Social Systems, p. 283.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid., p. 287.

-

Ibid., p. 286.

-

Ibid., p. 287.

-

Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness: A Phenomenological

Essay on Ontology, trans. Hazel E.Barnes (New York: Washington Square

Press, 1984) pp. 40–42.

-

Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or

Succeed (New York: Penguin Books, 2005) p. 431.

-

Ibid., p. 430.