Noisy Aesthetics

The term aesthetics is traditionally used to distinguish the appreciative from the expedient. The notion originated with a 1739 text by the German philosopher Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten (1714–1762) who introduced the term aesthetic in his text Meditationes Philosophicae de Nonnullis ad Poema Pertinentibus, defining it as the study of attraction as concerned solely with discriminating perception. For Baumgarten, in other words, aesthetics should be a separate, independent concern dealing only with perception. In Baumgarten's theory, much attention was concentrated on the creative act and the importance of feeling. For him, it was necessary to modify the traditional claim that “art imitates nature” by asserting that artists must deliberately alter nature by adding elements of feeling to perceived reality. In this way, the creative process of the world is mirrored in art activity. Baumgarten's thought in this regard was influenced by the philosophy of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) and that of Leibniz's pupil Baron Christian von Wolff (1679–1754).

The problems of aesthetics had been treated by others before Baumgarten, but he both advanced the discussion of art and beauty and set the discipline off from the rest of philosophy. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), who used Baumgarten's Metaphysica as a text for lecturing, retained Baumgarten's use of the term aesthetics as applying to the entire field of sensory knowledge. When combined with logic, aesthetics formed a larger discipline which Kant called gnoseology, a theory of knowledge that other philosophers called epistemology. Only later was the term aesthetics restricted to questions of beauty and of the nature of the fine arts.

Kant used the term aesthetics to argue that aesthetic appreciation reconciles the dualism of theory and practice in human nature, thereby leaving the way open to identify beauty (a relative, shifting and elusive concept) as a profoundly psychological quality (and not inherent in the artwork) by formulating a distinction between determinate, determinable, and indeterminate concepts. For him, beauty is non-determinate because we cannot know in advance whether something is beautiful or not by applying a set standard. He also deemed the concept of beauty non-determinable because, due to creativity, we will never find such a standard. Beauty, therefore, must reside in the indeterminate supersensible. And so must noise. This approach supports Walter Benjamin’s (1892–1940) conception of aesthetics not as a part of a theory of the fine arts, but as a theory of perception.

For me, such an approach to noise aesthetics was anticipated by Georges Bataille (1897–1962) [33] when he considered excess the non-hypocritical human condition, which he took to be roused non-productive expenditure (excess) entangled with exhilaration. Excess, for Bataille, is not so much a surplus as an effective passage beyond established limits, an impulse which exceeds even its own threshold. [34] When one takes an interpretative metaphorical view of noise—broader than the typical, somewhat fatuous, reductive explanations—one soon detects that the concept of noise itself is an open concept. [35] The concept of noise itself is pantheoristic. But in my use of the term (based on my activities as an artist) I understand art noise to be fundamentally an extravagant activity of creativity. [36]

However, a new meaning for noise in art (and in life) is not developed by thinking about the aesthetics of noise as an invasive and unpleasant return to a dark primal unconscious. [37] It works when noise is also understood as an expanded [38] psychic thermidor: when it takes us back from the edge and rounds out our sensibilities as it forces us to get with the underlying assumptions of excess inherent in noise. [39] As Allen S. Weiss says in his incisive book Phantasmic Radio, “Noise creates new meaning both by interpreting the old meanings and by consequently unchanneling auditory perception and thus freeing the imagination”. [40] This book is an attempt at facing up to the radical implications of those assumptions, and at purging us from conventional ways of thinking about noise (which is often disapprovingly).

This purging strategy provides a means of exemplifying various methods of thinking about noise. But it will not position noise in an easy opposition to Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s (1717–1768) codification of classical ideals as those being primarily uncomplicated and Apollonian in their logic, for when the idea of simplicity takes on the intensity of a righteous injunction, the implied equation between simplicity and goodness obscures a less evident function, that of cognitive constraint.

Plus noise today has become too subjective [41] and ambient for that kind of dialectic between Apollonian calmness in relation to Dionysian non-restraint. And too sublime, [42] with its mix of alarm, approval, apprehension, and ascendancy. As Edmund Burke says in his A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful: “The passions which belong to self-preservation, turn on pain and danger; they are simply painful when their causes immediately affect us; they are delightful when we have an idea of pain and danger, without being actually in such circumstances; this delight I have not called pleasure, because it turns on pain, and because it is different enough from any idea of positive pleasure. Whatever excites this delight I call sublime”. So this time, sublime immersion into noise promotes a conflicted but promiscuous ontological feeling (awareness/consciousness) where aesthetic cognition of the limits of the aesthetic attain the actual state of the generally subjective world of consciousness itself.

Pertinent to these noise concerns is, of course, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) and his acute criticism of the static culture of the bourgeoisie, particularly as it relates to the gesamtkunstwerkkonzept in Die Geburt der Tragödie (The Birth of Tragedy), Nietzsche's account of classical Greek drama and its merits. In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche procures the concepts of the Apollonian and the Dionysian principles from Greek tragedy. According to Nietzsche, the Apollonian principle: reasoned, restrained, self-controlled and organizing is subsumed within the Dionysian principle: that which is primordial, passionate, chaotic, frenzied, chthonic and creative. This dialectical aesthetic tension allows the imaginative power of Dionysius to operate, in that the products of this operation are kept intelligible by Apollonian constraint.

Hence Nietzsche examined the dialectic between an Apollonian calmness in relation to an antecedent Dionysian non-restraining tragedy which has its origins in the chants of the Greek chorus. By invoking the power of the Greek drama, Nietzsche implied a pejorative judgement on subsequent dramatic forms of realism and inert spectatorship. Generally speaking, this aspect of Nietzsche's thought thus participated in the widespread ideal embedded in Romanticism [43] of a popular recovery of the mythic precondition necessary for cultural consciousness based on, in most cases, the sublime excess of the infinite. [44]

In ancient polytheistic Greece, sacred rites were in certain cases enacted on or near sacred grove sites. One such well-recorded rite was the ecstatic Dionysian rite. The Dionysian rite was directed not at the nymphs however, but to Dionysos (also known as Dionysius, Bacchus and/or Bakchos), the God of wine, intoxication and creative ekstasis. Dionysian ecstatic festivities were based on an even earlier form of ritual, the ancient Springtime Spree which was a three-day agricultural gala which involved the uncasking and drinking of that year’s wine, the planting of seeds, and the encountering of ghosts. [45] By intoxicatingly mixing seeds with memories of their dead in the earth (which was viewed as the domain of the deceased) the ancient Greeks were able to incorporate their departed into the drinking and planting festival of the Spring Dionysia.

Subsequently the Spring Spree evolved into the even more intense rite of Dionysian ekstasis which intensified consciousness through drink and ecstatic prancing. The culmination of the Dionysian ekstasis rite was an ecstatic frenzy in which the dancers tore apart and devoured raw a sacrificial animal, such as a goat or a fawn. At the center of the rite are the mental states of ek-stasis and en-thusiasmós, states where psychological frontiers are torn down in preparation for the immersive divine dive into a world of animalistic unity.

As we will see further on, noise in art often evokes vast entropy [46] as a form of vacuole, even as entropy quantifies uncertainty in encounters with random variables. In his book, Poétique de l'espace (The Poetics of Space), Gaston Bachelard (1884–1962) speaks of the French poet Charles Baudelaire's (1821–1867) frequent use of the word vast, which is, Bachelard claims, one of the most Baudelairian of words: the word that marks naturally, for this poet, the infinity of the intimate. This, at first seemingly paradoxical statement, is correct, for Baudelaire is above all celebrated as a poet and practitioner of double consciousness: incarnating two intertwined natures. Apparent polar opposites play against (and ultimately with) each other dialectically in his thinking.

In comparable ways, art noise is both decadent and sublime when it is founded on vacuole principles of debauchment and self-indulgent consternation. Of course, such a dithyrambic logic has manifested in all modes of decadent artistic periods, from the Hellenistic and Flamboyant Gothic, to the Mannerist, Rococo, and Fin-de-Siècle, as they all opposed dogmatically imposed paradigms with hyper-engendering strategies. This is precisely what art noise does today. Because of noise’s stimulation of the nerves, the decadent sublime (as safe terror) is agreeably engaging (particularly in grating harsh noise music) [47] even as this psychologically intense feeling is bound up with our sense of mortality in an existential way similar to the terms of Jean-Paul Sartre's (1904–1980) Being and Nothingness. Indeed the term sublime specifically refers to an aesthetic vacuole value in which the primary factor is the presence or suggestion of undivided vastness and immense breadth of space, which is incapable of being completely ascertained.

Noise art (musical and visual) therefore never offers us conventions. Rather, when good, it is like a fertile seedbed which undermines the hitherto clear, false distinctions between representation (identity) and the imagination by way of negating and recombining. Here, semblances and sounds are always already connected within a crushed and dark and obscure excessive orb, as noise art negates artistic representations (and all they imply), thereby affirming a consciously divergent way of perceiving and existing. Such excessive artistic noise can therefore spawn in us a sense of affinity which communicates individuality in totality without forfeiting liberty.

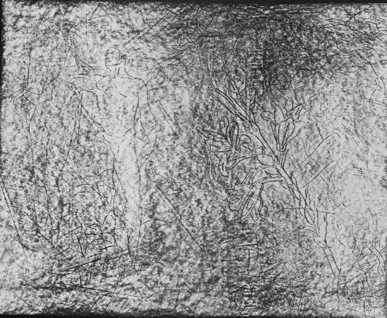

I should say that several of my ideas on this subject of noise stemmed from reading Georges Bataille's Visions of Excess (which appeared in English translation in 1985) after which I began to experiment with (and analyze through my artwork) various artistic approaches towards noise and excess. [48] In the terms Bataille proposes, any “restricted economy”, any sealed arrangement (such as an image, an identity, a concept or a structure) produces more than it can account for, hence it will be inevitably fractured by its own unacknowledged excess and, in seeking to maintain itself, will, against its own rationalized logic, crave rupture, expenditure, and loss. More specifically, for Bataille, the term expenditure describes an aspect of erotic activity poised against an economy of production. [49] Yet Bataille's accomplishment transgresses disciplines and genres so repeatedly and so thoroughly that capsule accounts of his work in terms of noise are compelled to delegate themselves to abstractions. One can say with assurance that his thinking consisted of a meditation on, and fulfilment of, transgressions through excess. Thus Bataille's Visions of Excess immediately impressed me as it resonated handsomely with the overloaded nature of my palimpsest-like grey graphite drawings from the early-1980s (which were reflective of the time's concerns with the proliferation of ideology connected to the proliferation of nuclear weapons).

So via Bataille, I can say that noise art’s probing at the outer limits of recognizable representation, the excited all-over fullness and fervor of this syncretistic probe, isn't a failing of communications in the art; it is its subject. Good noise art, for me at least, is capable of nurturing a sense of polysemic uniqueness and of individuality brought about through its counter-mannerist style (circuitous, excessive and decadent); it is a style that takes me from the state of the social to the state of the secret, distinguishable I by overloading ideological representation to a point where it becomes non-representational. It is this non-representational counter-mannerist representation which breaks us out of the fascination and complicity with the mass media mode of communication. Noise art frees us, then, from accustomed coyness, platitudes, and predetermined perceptions with which we are deluged daily by the mass-pop media. It is my experience that it is in this artistic condition of privately excessive formlessness that we can ascertain the delimitation of mass-pop media ideology and the resultant implications of that cognizance.

Notes

-

Librarian, libertine, paleologist, archivist, radical thinker, author of erotic fiction; Bataille took an active role in the mid-20th century Parisian avant-garde art and literary scene by objecting to what he saw as the aestheticism and sentimentality of the Surrealists. Consequently he became André Breton's (1896–1966) antagonist from the intellectual ultra-left. After World War II, as founding editor of the journal Critique and after authoring the transgressively philosophical books L'Expérience Intérieure (Inner Experience) (1943), Le Coupable (Guilty) (1944), Sur Nietzsche (On Nietzsche) (1945) and La Part Maudite (Accursed Share) (1947), Bataille's thought emerged as a viable alternate to Jean-Paul Sartre's then reigning philosophical school of Parisian Existentialism.

-

For Georges Bataille, examples of non-productive excess/expenditure can be found (in varying degrees) in forms of luxury, lamentation, spectacle, art, poetry, erotic activity and mystical endeavours; some of which place an emphasis on a loss that must be as great as possible in order for that activity to take on its fullest meaning. For the finest comprehensive overview of Bataille's thought in this regard, see his book Eroticism, trans. Mary Dalwood, intro. Colin MacCabe (London: Penguin, 2001), along with Denis Hollier's book on Bataille's general postulates, Against Architecture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990).

-

As is art. Piet Mondrian has made the valid point that fine art is not made for anybody and is, at the same time, for everybody.

-

I should establish that the pantheoristic definition of noise in art which I am upholding here, and which I find requires reiteration as artists move increasingly from organic materials to the use of electronic and synthetic ones, is basically that supplied by Susanne Langer in her book Feeling and Form where she determines that "art is the creation of forms symbolic of human feeling,” Susanne K. Langer, Feeling and Form (NJ: Prentice Hall, 1953) 40.

-

Indeed Leon Cohen in his paper “The History of Noise” makes a case for noise being involved in the solution of some key scientific, mathematical and technological problems.

-

When I use the terminology expanded here I am referring to the rich meaning given to it by Gene Youngblood in his book Expanded Cinema as that which transgresses and exceeds the customary boundaries of our encounters. When Youngblood discusses what he calls "expanded cinema" he refers it to an "expanded consciousness,” Gene Youngblood, (New York: E. P. Dutton and Co, Inc. 1970) 41.

-

In science, and especially in physics and telecommunication, noise is fluctuations in and the addition of external factors to the stream of target information (signal) being received at a detector. White noise is always present.

-

Allen S. Weiss, Phantasmic Radio (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995) 90.

-

In philosophic terms, subjectivity denotes how the truth of some privileged class of statements depends on the mental state or reactions of the person making the statement. In epistemology, subjectivity is knowledge that is restricted to one's own perceptions. This implies that the qualities experienced by the senses are not something belonging to the physical beings, but are subject to interpretation. In metaphysics, subjectivity includes the idea of solipsism. In aesthetics, subjectivism is the view that statements about beauty (for example) are not reports of "objective" qualities inherent in things but rather cognitive reports of internal feelings and attitudes.

-

The concept of the sublime as such first emerged as the topic of an incomplete treatise entitled "On the Sublime" that is believed to have been written in the mid-third century AD by Cassius Longinus (third century AD). The author of the treatise defines sublimity as: (1) excellence in language, (2) the expression of a great spirit, and (3.) the power to provoke ecstasy. The immersive sublime, from the combined point of view of Cassius Longinus's last two definitions, is apprehended and grasped as a totality while at the same time experienced as exceeding our usual lucidity, therefore provoking a sensation of awe (as recognized by Longinus). Centuries later, the term was given special prominence by Edmund Burke (1729–1797) in his A Philosophical Enquiry Into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), one of the most popular 18th century treatises on aesthetics, which was translated into French in 1765 and into German in 1773. According to Burke, the sublime feeling (which contrasts with that of the beautiful) is caused by a mixture of terror, admiration, apprehension, and supra-attention. Burke maintained that the life of the spirit depends on this type of awe in agreement with the immense scheme of the universe.

-

Romanticism (circa 1795–1840) is the cultural movement inspired by the writings of Edmund Burke (1729–1797) and the French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), (among others) that focused on individual passions and inner struggles and hence produced a new outlook and positive emphasis on the emotional artistic imagination which became perceived as a gateway to transcendent experiences of unity.

-

Torben Sangild points out in his essay "The Aesthetics of Noise" that in Genèse, French philosopher Michel Serres sketched out the idea that the ultimate being-in-itself is noise. Behind the phenomenal world (the world we perceive)—he proposes—is an infinite complexity, an incomprehensible multitude analogous to white noise. (http://www.ubu.com/papers/noise.html accessed 1/15/2008). What Serres initially finds intriguing about noise (rather than the message) is that it opens up a fertile avenue of reflection. Instead of remaining pure noise, it becomes a means of transport. Also, Serres addresses the theme of noise and communication to show that 'noise is part of communication'; it cannot be eliminated from the system.

-

Jane. Ellen Harrison, Ancient Art and Ritual (Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts: Moonraker Press. 1913) 80.

-

In information theory, entropy is a measure of the uncertainty associated with a random variable.

-

Harsh feedback sounds are tones that may have drone-like charactistcs or swarm chaotically.

-

Bataille has remained a great fascination, though always slightly out of distance, given his penchant for violence, as I am largely a pacifist, politically. I believe in the political effectiveness of civil disobedience and passive résistance. So he is always pithily slipping from my mental fingers. But with his last book, The Tears of Eros, he provided the inspiration for my art to attempt a visual sagacity that tests the limits of form and stretches the bounds of meaning by recasting our experiences of encountering wildly disjunctive phantasmagoric data on the Internet into the sumptuous physicality of negation. In that sense, he turned my work against the grain of its prior obsession with fabricating a complicated forensic fairy-tale out of the internet’s grisly mélange, a mélange which keeps slipping in and out of idiosyncratic narration as it keeps folding and unfolding. When I went to Vézelay to visit his tomb, I searched the cemetery for something like two hours, reading each headstone meticulously. But I was unable to discover his grave! Merde! I had hoped to leave a little perverse poem and perhaps defecate on it, but no luck. In that sense I am reminded that frustration often amplifies desire and that this is essential to noise in art also.

-

Georges Bataille, Visions of Excess (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985) 116–29.