2. Magic Birth

Brekekekex, ko-ax ko-ax! The frogs were croaking in the pond near the house. There must have been tens of thousands of them. Humans hear the croak and translate it: into the word croak, for instance. Aristophanes translated it into the rhythmically fancy brekekekex, ko-ax ko-ax. [1] Croak or ko-ax, it’s not too bad a translation, or to use the strict term for the figure of speech, onomatopoeia. Frogs don’t go boing or clunk. They croak. Somehow these nonhuman sounds made it into human language, altered but reasonably unscathed. A new translation has appeared. A fresh Rift has opened up between appearance and essence. An object is born.

A wall of croaking filled the night air. Hanging on either side of a human head, a pair of ears heard the sound drifting over the pond towards darkened suburbia. A discursive thought process subdivided the wall of sound, visualizing thousands of frogs. A more or less vivid, accurate image of a frog flashed through the imagination. The soft darkness invited the senses to probe expectantly further into the warm night. On the breeze came the wall of sound, uncompromising, trilling like the sound of frozen peas rattling around inside a clean milk bottle multiplied tens of thousands of times. While the author was writing the preceding sentence, a whimsical taste for metaphor enjoyed linking the sound of the frogs with the sound of frozen vegetables. (It’s not easy being green?)

Air was forced into an elastic sac at the bottom of a frog’s mouth. The lungs pushed and the sac inflated, and when released out came the croak. The air was modulated by frog tissues, sampled briefly and repackaged, returning to the ambient atmosphere as a low rasp with high harmonics. The sound was made of myriad waves crisscrossing in the air. Fetid smells of the damp swamp at the edges of the pond drifted indifferent to the frog chorus, reaching the nose of a little girl who said they reminded her of the seaside. The air carried sound and smell and a soft touch to the skin.

A single sound wave of a certain amplitude and frequency rode the air molecules inside the frog’s mouth. The wave was inaudible to a mosquito flying right past the frog’s lips, but sensed instead as a fluctuation in the air. The wave carried information about the size and elasticity of the frog’s mouth, the size of his lungs, his youth and vigor. The wave spread out like a ripple, becoming fainter and fainter as it delivered its message further and further into the surrounding air. Ten thousand feet above the pond, passengers in a plane failed to hear the sound wave, although a faint glint of the plane’s landing lights was visible as a brief wink of color reflected from the surface of the water. Reaching the ears of a nearby female frog, however, the sound wave was soon translated into hormones that told her that a young stud frog was close by. The wall of croaking caused the grasses in the pavement next to the pond to vibrate slightly.

Fingers switched on an MP3 recorder outside the suburban house. The wave front entered the microphone along with countless of its sonic cousins. A software driven sampler took 44,000 tiny impressions of the sound per second and stored it in the device’s memory.

As the wave front advanced, the shape of the wave remained fairly constant as molecule after molecule translated it into its own vibration. The expanding wave front brushed against the outermost rim of a spider’s web, causing the spider to detect in her feet the possible presence of the next meal. Like a plucked violin string, one thread of the web moved slightly back and forth. [2] There were minuscule momentary differences in pressure on either side of the thread. A tiny drop of dew fell from the vibrating thread, impacting on the surface of a stone below, exposing millions of microbes to the surrounding air. Several moments later, the author of a book called Realist Magic remembered the sound of the frogs in the pond and wondered what else might have been going on in and around that sound.

Actual, real things are happening at multiple levels and involving multiple agents, as the wave front of the single sound wave from the frog’s mouth traverses the pond to my ears. The wave becomes imprinted on the air, on the spider’s web, in the human ear. Each packet of air molecules translates the wave from itself to the next packet: trans-late means “carry across,” which is also what meta-phor means. I hope you are beginning to see how causality and aesthetic “information” are deeply bound up with one another.

Every object is a marvelous archaeological record of everything that ever happened to it. This is not to say that the object is only everything that ever happened to it—an inscribable surface such as a hard drive or a piece of paper is precisely not the information it records, for the OOO reason that it withdraws. Precisely for this reason, we can have records, MP3s, hard drives, and tree rings. We can also have the Universe—the largest object we know. Evidence of it shows up everywhere—one percent of TV snow is the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation left over from the Big Bang. The more widespread is the evidence of a thing in the form of other beings, the greater its power and the deeper its past. Thus the more basic a character trait is, the further it has come from the past of a person. Five proteins found in all lifeforms are evidence of LUCA, the Last Universal Common Ancestor, thought to be a gigantic ocean creature with very porous cells. These proteins are now manufactured differently than they were in LUCA, but it is as if our bodies—and the bodies of geckos and bacteria—keep on reproducing them anyway, like lines from the Bible accidentally woven into the everyday speech of a twenty-first century atheist. Likewise Heidegger thought that philosophy had forgotten being so deep in the past that evidence of its forgetting was as it were everywhere and nowhere.

If we could only read each trace aright, we would find that the slightest piece of spider web was a kind of tape recording of the objects that had brushed against it, from sound wave to spider’s leg to hapless housefly’s wing to drop of dew. A tape recording done in spider-web-ese. Thus Jakob von Uexküll refers to the marks (Merkmalträger) of the fly in the spider’s world. [3] Although the two worlds don’t intersect—the spider can’t know the fly as the fly, and vice versa—there are marks and traces galore. Thus Giorgio Agamben, interpreting Uexküll’s insight, writes about a forest:

OOO adds: yes, but let’s not forget the forest-for-the-spider, the forest-for-the-spider-web, the forest-for-the-tree, and last but not least, the forest-for-the-forest. Even if it could exist on its little ownsome, a forest would exemplify how existence just is coexistence. To say that existence is coexistence is not to say that things merely reduce to their relations. Rather, it is to argue that because of withdrawal, an object never exhausts itself in its appearances—this means that there is always something left over, as it were, an excess that might be experienced as a distortion, gap, or void. In their very selves, objects are “a little world made cunningly,” as John Donne writes. [5] This is because of the Rift: the being of things is hollowed out from within. It is this Rift that fuels their birth.

Causality as Sampling

Let’s return to that wave front of the frog croak. It seems as if each entity samples the wave front in different ways. There is the wave front as sampled by the mosquito as a sheer change in pressure, for instance. The vibrating thread of the spider’s web announces the presence of a possible meal in the web to the waiting spider. Yet a single entity, the wave front, is what is being sampled in each moment. It’s like a pop song. You can get the CD, the vinyl, the cassette, the MP3, the twelve-inch dance remix, the AIF, the WAV—or you hear it one day blaring out of some cheap transistor radio buzzing with interference. In each case you have a sample, a footprint, of the song. The song has a form. The vinyl has a form. Special tools engrave the vinyl with the form of the song. A laser cuts tiny holes in the plastic surface of a CD, translating the song into a sequence of holes and no-holes.

Let’s analyze that MP3 recording of the croaking frogs. It’s a translation of the frog sound as much as the word “croak” or Aristophanes’ elaborate brekekekex, ko-ax ko-ax. First we select two seconds of the croak. A computer terminal translates the sound into a visual image of a wave. A special software application introduces zeroes into the wave so that each little piece of the wave become visible between increasingly stretched out sequences of space. A tiny piece of the wave that is two seconds of frog croak is a sequence of clicks. Speed up the clicks and we have a croak. At a very small scale, the wave is a series of beats, like the beats of a drum. These beats occur when one sound interrupts another. Think of a line. Now introduce a gap into the line—interrupt it: you have two lines. The space between them is a beat. In music composition software, one sample can be broken up according to the rhythm of another one, giving rise to an effect commonly known as “gating.” A voice, for example, can break up into the scattered patter of hi-hat beats or snare drum shots, so that a smooth-seeming “Ah” can become “A-a-a-a-a-ah.”

Think of a straight line. Then break it into two pieces by chopping the middle third out. Now you have a beat, the space between the lines; and two beats, the lines. Then chop the middle thirds out of those lines. You have some more beats. And more beats-as-lines. Eventually you end up with Cantor dust. It is named after Georg Cantor, the mathematician who discovered transfinite sets—infinite sets of numbers that appeared to be far larger (infinitely larger) than other sets of infinite numbers. Cantor dust is weird, because it has infinity pulses in it, and infinity no-pulses. Infinity beats and infinity beats-as-lines: p ∧ ¬p. This paradoxical fact is the sort of discovery that reinterpretations of Cantor have sometimes striven to edit out, most notably, the Zermelo-Fraenkel theory preferred by Alain Badiou. [6] We have seen this formula before, in our first foray into the world of fundamentally inconsistent objects. It is not surprising that we encounter it again here. Why?

The amalgam of beats and no-beats is also what happens at a smaller physical scale. Single waves break into and are broken by others. Sound cuts into silence. Silence cuts into sound. We have arrived at a very strange place. In order for a frog croak to arise at all, something must be there, yet missing! Some continuous flow, say of frog breath inside a frog’s mouth, must be interrupted somehow, to produce a beat. There must always be at least one extra sound or non-sound that the beat cuts into. [7] For the mathematically inclined, this is reminiscent of Cantor’s astonishing diagonal proof of transfinite sets, that is, of “infinities” larger than the infinity of regular whole numbers, or of rational numbers (whole numbers plus fractions). Say we look at every number between zero and one. Cantor imagines a grid in which you read off each number between zero and one in the series across and down. Yet every time you do this, a number appears in the diagonal line that cuts across the grid at forty-five degrees, a number not included in the set of rational numbers. Astoundingly, something is always left out of the series! [8]

We could argue that Cantor had discovered something about entities of all kinds or, as I call them here, objects. Cantor discovered that objects such as sets contain infinite and infinitesimal depths and shadows, dark edges that recede whenever you try to take a sample of them. The set of real numbers contains the set of rational numbers but is infinitely larger, since it contains numbers such as Pi and the square root of 2. There appears to be no smooth continuum between such sets. So the set of real numbers contains a set that is not entirely a member of itself—the set of rational numbers sits awkwardly inside the set of real numbers, and it is this paradox that infuriated logicians such as Russell. Their “solution” is to rule this kind of set not to be a set—which is precisely to miss the point.

Returning to our croaking frog, no matter how many times you sample his voice—recording it with an MP3 player, hearing it with your spider’s feet, enjoying it as an indistinct member of a thousand-strong frog chorus—you will not exhaust it. And that’s not all. The croak itself contains inexhaustible translations and samples of other entities such as the frog’s windpipe and the frog’s sex hormones. The croak itself is not identical with itself. And no croak sample is identical with it. There is no whole of which these parts are the sum, or which is greater than their sum. There just can’t be. Something always escapes, something is always left out for a beat to occur. “Beat” implies “withdrawn object.”

What happens when you take the smallest thinkable unit of beat? This is what physicists call a phonon. A phonon is a quantum of vibration, just as a photon is a quantum of light. When you pass a phonon through a material sensitive enough to register its presence, such as a tiny supercooled metal tuning fork visible to the naked eye, you see the fork vibrating and not vibrating at the same time. [9] Recall that Aaron O’Connell, who designed the experiment, describes this state in a lovely way as “breathing.” This breathing is visible to humans. O’Connell employs the analogy of someone alone in an elevator: they are liable to do all kinds of things that they would feel inhibited about in public. [10]

To achieve this magic you have to pass the phonon through a qubit. A qubit, unlike a classical switch, can be ON, OFF, or both OFF and ON. As if to defy our wish to reduce objects to fundamental particles, the tiniest amount of vibration possible, when we preserve its fragile being by passing it through the qubit into a crystal lattice (metal) at just above zero Kelvin (absolute zero), causes nothing and something, overlapped. It’s as if the beat and the no-beat happen at once. An extra layer of mystery springs out before our very eyes; this experiment can be seen by humans without prosthetic aids, thus making it extra strange, given standard prejudices about the scale on which quantum phenomena should occur.

The unit of vibration doesn’t happen “in” space or “in” time if by that we mean some kind of rigid container that is external to things. It seems as if time itself and space itself are in the production of these differences, these beats, everywhere. [11] But because of the regularity of our timekeeping devices, we humans ironically expect things to behave mechanically, even though physics tells us that this just can’t be the case, at least not in some fundamental sense. The gate of a sampler snaps open and closed in one forty thousandth of a second. It records, inscribes, a certain chunk of croak. A quartz crystal in a digital clock in the MP3 recorder vibrates. It tells you that the frog croak was recorded at such and such a time. It tells the time in quartz-ese, just as the metal cogs and springs in an old cuckoo clock tell the time in coggish and springish. “Telling the time” is a telling phrase that reveals more than it lets on. To tell is to speak and thus to translate—electronic quartz vibrations into human, for instance. To tell is also to count or to beat time. The periodic clicks of the frog tell out measured beats. Reality in this sense is a gigantic pond in which trillions of frog-like entities are croaking at different speeds, across one another, through one another, modulating and translating one another.

Going up a scale or two (and then some), the little night pond with its chorus and its softly swaying reeds and grasses can be seen from a spy satellite in geostationary orbit. A timeless photon bounces off the frog’s eye. The photon shoots back into space where it passes through the sampling devices in the satellite’s camera. At this scale information fans out at the speed of light into the Universe in a gigantic cone, a cone that Hermann Minkowski called the light cone. If some passing alien vessel equipped with superb telescopes were able to receive photons from the frog’s eye, the aliens would be able to figure out when the photons bounced off of the eyeball, and where their ship was in relation to the eyeball. But if the alien vessel passes outside the light cone emanating from the croaking frog, it becomes meaningless to them whether the frog is croaking in their past or their future or their present. There is simply no way to find out. At this macro scale, then, the Universe also seems to behave as if objects in it are mysteriously withdrawn—events start to lose their comparability with other events, so that we can’t tell when and where they happen unless we’re within a certain range defined by the light cone. If Einstein is right, then this realization also affects the frog himself. Place a tiny clock on the frog’s tongue. It will tell a different time from the tiny clock you place on the wing of the passing mosquito as it flies.

Quantum theory and relativity theory put all kinds of limits on seeing our pond as an intricate machine. Machines need rigid parts operating smoothly in an empty container of time and space. The materialists in the infinite-Universe and empty-space-as-container crowd adapted what was ironically a neo-Pythagorean piece of mysticism from Augustine and other theologians, who were the first to argue for infinite space—an argument that was enforced by the Pope himself. [12] Now the Big Bang theory is well established, but most post-Newtonian physicists assumed that the Universe had to be eternal. Yet several hundred years before that, an Arabic Aristotelian not subject to Papal edicts figured it out. Speculative metaphysician al-Kindi used a bit of Aristotle and some clear reasoning to argue that the Universe couldn’t be infinite or eternal. Using Aristotle against Aristotle, he reasoned that since a physical thing can’t be infinitely large, and since time is an aspect of the physical Universe, the Universe can’t be eternal. [13] (Aristotle himself thought that since the motion of the heavens was perfect, the Universe had to be eternal.) If the Universe were eternal, it would have taken infinity days to get to this one. This means that today couldn’t arrive. So the Universe isn’t eternal.

The last century of physics makes it extremely unlikely that our pond is a machine in any but a fanciful sense. Maybe the croaking of fifty thousand frogs does remind you a little of a department store full of wind-up toys all malfunctioning simultaneously. There is a periodicity, a regular repetition, to the beats, that makes it seem as if what is happening is mechanical. And biology likes to use machinery to imagine how lifeforms do things like croaking. But from the point of view of fundamental physics this machinery is really only a reasonably good metaphor.

Yet for quite some time, at least since the seventeenth century, humans have been used to thinking that causality has something mechanical about it, like cogwheels meshing together or little balls in an executive toy clicking against one another. Yet even when we examine cogwheels and balls, what we find is far more curious than that. For instance, if you make really tiny nanoscale cogwheels, when you place them together you may find that they don’t spin, because to all intents and purposes they have become an item. Casimir forces have glued them together even though they haven’t properly touched. When a tiny, tiny ball smacks against a crystal lattice, it might bounce off or it might go in—or it might do both.

As we saw in the Introduction, when we think of causality, what we think of is some kind of clunking. But think of the hormones in the frog’s endocrine system. In a chemical system, there may be no obvious moving parts, yet a catalyst might cause a reaction to occur. It might not be best to think of the frog’s sexual stimulation in terms of one ball hitting another (pardon the awkward double entendre). It might be better to think of a transfer of information—it might be better to think that causality is an aesthetic process.

We’ve seen how events begin via some kind of aesthetic phenomenon. This isn’t a quaint notion. In fact, it may be far less quaint than the images of clunk causality. How come nanoscale cogwheels can get glued together through Casimir forces? How come a tiny tuning fork can vibrate and not vibrate simultaneously? How come “past” and “future” are meaningless outside the light cone? Don’t all these phenomena compellingly suggest the possibility that when we look for causality like someone opening the hood of a car, to inspect the machinery underneath, we might be looking in the wrong place? The magic of causation, in other words, might be magic in the sense that it happens right before our eyes, in the aesthetic dimension. As stated before, the best place to conceal something is right in front of the security camera. No one can believe it’s going on. What remains to be explained, in other words, is not the blind mechanics underneath the hood, but the fact that things seem to happen at all, right here.

Might the search for a causal machine underneath objects be a defensive reaction to the fact that causality is a mystery that happens right under our nose, but that’s inexplicable without recourse to the aesthetic, and without seriously revising a whole bunch of assumptions we’ve made about the world since the seventeenth century? The gradual restriction of philosophy to a smaller and smaller shrinking island of human meaning in a gigantic void only served to confirm these assumptions. In parallel with this sad course of events, the arts and the aesthetic dimension of life are seen increasingly as some kind of fairly pleasant but basically useless candy sprinkles decorating the surface of the machinery. I shall be arguing for the exact opposite. The machinery is the human fantasy, and the aesthetic dimension is the very blood of causality. An effect is always an aesthetic effect. That is, an effect is a kind of perceptual event for some entity, no matter whether that entity has skin or nerves or brain. How can I even begin to suggest anything so outlandish?

One way to start thinking about why it might be compelling and even reasonable to think this way is to examine whether there is anything all that different about my perception and the perception of a frog, or for that matter, the perception of a spider, or indeed of a spider’s web. Rather than going the route of claiming that cinder blocks have minds, let’s go the other way—let’s imagine how being mindful of something is like being a cinder block. We can take comfort here from the hardest of hardcore evolutionary theory. If we think perception is some kind of special bonus prize for being highly evolved, then we aren’t being good Darwinians. That’s a teleological notion, and if Darwin did anything, it was to drive a gigantic iron spike rather impolitely through the heart of teleology. The frog croaking in the pond is just as evolved as me. He might well have more genes for all I know. Fruit flies have more genes than humans. Genetic mutation is random with respect to present need. Brains are quite ungainly kluges stuck together over millions of years of evolutionary history. Maybe the point is that when a brain styles the world according to its brain-ish ways, this is not unlike how a cinder block styles the world in cinder block-ese. Why?

When I listen to the frog croaking, my hearing is carving out audible chunks of frog croak essence in a cavalierly anthropomorphic way. When the MP3 recorder takes a perforated sample of the same sound forty thousand times a second, it MP3-morphizes the croak just as mercilessly as I anthropomorphize it. The croak is heard as my ears hear it, or as the recorder records it. Hearing is hearing-as. It’s an example of what Harman, via Heidegger, calls the as-structure. My human ears hear the frog as human ears. The digital recorder hears the frog as a digital recorder. The spider web hears the frog in a web-morphizing manner. The ears otomorphize; the recorder recorder-morphizes. When you hear the wind, you hear the wind in the trees—the trees dendromorphize the wind. You hear the wind in the door: the door doormorphizes the wind. [14] You hear the wind in the wind chimes: the chimes sample the wind in their own unique way.

Interobjectivity Revisited

Another way to say this is that the wind causes the chimes to sound. The wind causes the doorway to moan softly. The wind causes the trees to shush and flutter. The frog causes the spider web to waver. The frog causes my eardrum to vibrate. It’s perfectly straightforward. Causality is aesthetic.

This fact means that causal events never ever clunk, because clunking implies a linear time sequence, a container in which one metal ball can swing towards another one and click against it. Yet before and after are strictly secondary to the sharing of information. There has to be a whole setup involving an executive toy and a desk and a room and probably at least one bored executive before that click happens. Clunk causality is the fetishistic reification, not sensual causality!

Objects seem to become entangled with each other on the aesthetic level. Now quantum entanglement is beginning to be quite a familiar phenomenon. You can entangle two particles, such as photons or even small molecules, such that they behave as if they were telepathic. Over arbitrary distances (some think there is no limit) you can tell one particle some information, and the other particle seems to receive the same information simultaneously. [15] Spatiotemporal differences are meaningless when it comes to quantum entanglement. What if this were also the case with salt cellars and fingers, or with ponds and night air, or MP3 players and sound waves? Causality is how things become entangled in one another. Causality is thus distributed. No one object is responsible for causality. The buck stops nowhere, because causality means that the buck is in several places at once. It’s two days since I first heard those frogs, and here I am, still writing about them. The entanglement spreads across time. Or rather, I tell the time according to the croak rhythms in which I am entangled. “Yesterday” is a relationship I’m having with quartz, sunrise, gravity and a persistent sore throat.

Another way to say this is that causality is interobjective. We began to explore this in the previous chapter. To reiterate, we are fairly familiar with the term intersubjectivity. It means that some things are shared between subjects. For instance, I am someone several people think of as Tim. Tim is an intersubjective phenomenon. Small children talk about themselves in the third person because they haven’t yet internalized this fact. They refer to themselves as someone else, and in so doing they are speaking the truth. But here I’m claiming that intersubjectivity—indeed, what we call subjectivity in any sense whatsoever—is a human-shaped piece of a much vaster phenomenon: interobjectivity. This has far-reaching implications. It’s efficient to describe phenomena such as subjectivity and mind as interobjective affairs. A brain in a bucket, a brain on drugs, a brain in a functioning forty-year-old man: these are all different interobjective states. Intersubjectivity is just a small zone of human meaningfulness in a vast ocean of objects, all communicating and receiving information from one another, frogs in the pond of the real. Thinking the mind as a substance “beneath” the interobjective sensual realm, a tradition begun by Theophrastus, results in all kinds of puzzles, as the Arabic philosopher Ibn Rushd pointed out. [16]

Interobjectivity means that something fresh can happen at any moment, because in any given situation—in any given configuration of objects—there are always 1+n objects more than needed for information sharing. The frog croak travels across the pond. The water aids the smooth transmission of the sound waves into the ambient air around the pond. But the grasses at the edge of the pond absorb some of the sound, imprinting it with their own slender rustle by canceling some of it out. When I hear the croak as I turn the key in the garage door, I’m hearing a story about air, grasses, water and frogs. It’s a frog croak plus n objects. The sound doesn’t travel through empty space. It travels through an object in which there reside other objects. For example, the sound travels through a light cone in which various planets, galaxies, and vacuum fluctuations exist. The sound travels through West Coast U.S. suburbia. The sound travels through a society of frogs. There is no world, strictly speaking—no environment, no nature, no background. These are just handy terms for the n objects that make it into interobjective relationships with whatever’s going on. There is simply a plenum of objects, pressing in on all sides, leering at us like crazed characters in some crowded Expressionist painting.

Interobjectivity is the uterus in which novelty grows. Interobjectivity positively guarantees that something new can happen, because each sample, each spider web vibration, each footprint of objects in other objects, is itself a whole new object with a whole new set of relations to the entities around it. The evidence of novelty cascades around the fresh object. The human-shaped frog croak I hear inspires me to write a chapter in my book on causality. The MP3-shaped frog croak squats in the memory of the chip in the recorder, muscling other data out of the way. The web-shaped frog croak deceives the spider for half a second, luring her toward the source of the disturbance. And a human eyeball remains indifferent to the croak, focused as it is instead on the eyelash that has come adrift on its wet milky surface. Objects are ready for newness, because they have all kinds of pockets and redundancies and extra dimensions. In short, they contain all kinds of other objects, 1+n.

If an object’s beginnings were the beginning of a story, it would be called aperture. Since causality is aesthetic, aperture is precisely what we shall call it when a new object is born. What is aperture—what can we learn from aesthetic objects with which we’re familiar? Can we extrapolate from this to other kinds of objects and to object–object interactions? For this, we can handily return to Aristotle. His notion of formal cause comes in very useful for thinking about artworks as substances, that is, as objects with a specific shape, a specific contour and line. The deep reason why this will be useful for us is that artworks do origami with causality, folding it into all kinds of unusual shapes for us to study.

Aperture: Beginning as Distortion

Think of a story as a certain kind of form. Aristotle was right about stories. They have a beginning, a middle and an end, he argues. [17] When I first read this I felt exasperated. Tell me something I don’t know, Aristotle! Look, here’s the beginning of a story (page 1). Here’s the middle (total number of pages divided by two). And here’s the end (final page). Of course this is not what Aristotle means. What he means is that stories have a feeling of beginning (aperture), a feeling of middle (development), and a feeling of ending (closure). Depending on the story, these feelings can be more or less intense and last for different durations.

Beginnings, middles and ends are sensual. In other words, they belong to the aesthetic dimension, the ether in which objects interact. Any attempt to specify a pre-sensual or non-sensual beginning, middle or end will result in aporias, paradoxes and dead ends. Since objects love to hide, to adopt Heraclitus’ well known saying about nature, chasing the way they begin, continue or end will be like trying to find the soap in the bath.

So what is aperture, the feeling of beginning? Maybe thinking this through can give us some clue as to how objects begin. Stories begin with flickers of uncertainty. As the reader you have no idea who the main character is. You have no idea what counts as a big or small event. You have no idea whether the persistent focus of the opening chapter on a living room in suburban London in the late Victorian period will become significant. Every detail seems weird, floating in a bath of potential significance. You are uncertain whether the story proper has begun at all. Is this just a prologue?

Imagine listening to the story on the radio. Imagine switching on the radio at some random moment and catching a snatch of the story. Would you be able to tell, just from the way the narrator was telling the story, whether you were at the beginning, the middle, or the end? If the story happens to be a realist story, written from about 1790 on, you may be in luck. There are quite precise rules for performing aperture, development and closure in a realist narrative. Now obviously I’m not going to argue that real reality corresponds to a realist narrative. But aesthetic realism gives us some useful tools for thinking about how art can convey a sense of newness, familiarity, and finality. And since causality is a kind of art, there is reason enough to do some investigating. Note, however, that a realist novel is not necessarily realist in the way that an ontology is realist. It is just that realist novels have quite clearly defined parameters for what counts as a beginning, a middle and an end.

We’ve spent some time in a nursery for objects, the pond across the way from my house. Now let’s see what happens when we witness the birth of an object. How do objects begin?

Crash! Suddenly the air is filled with broken glass. The glass fragments are fresh objects, newborn from a shattered wine glass. These objects assail my senses and, if I’m not careful, my eyes could get cut. There are glass fragments. What is happening? How many? How did this happen? I experience the profound givenness of beginning as an anamorphosis, a distortion of my cognitive, psychic and philosophical space. [18] The birth of an object is the deforming of the objects around it. An object appears like a crack in the real. This distortion happens in the sensual realm, but because of its necessary elements of novelty and surprise, it glimmers with the real, in distorted fashion. Beginnings are open, disturbing, blissful, horrific.

The puzzled questions that necessarily occur to me at the start of a story are all marks of aperture, the feeling of beginning. Since aesthetics plays a fundamental role in object-oriented ontology, let’s think about the aesthetics of beginning. The feeling of beginning is precisely this quality of uncertainty, a quality well established at the beginning of Hamlet, whose first line is a question: “Who’s there?” [19] Isn’t that the quintessential issue at the beginning of a drama, whether it’s a movie or a play? Who is the lead character? Who are we watching now? Are they minor or major characters? How can we tell? We can’t. Only when the movie or play has continued for some time can we figure this out.

Aperture is distortion (anamorphosis), the absence of a reference point. Nothing has happened yet, since “happening” is paradoxical: it requires at least two things to occur, as Hegel argued. In addition, aperture is flexible. It can be stretched and it can be compressed. You can have beginnings that throw you right into the story with little need for figuring out who is who: action movies are good examples. You can have beginnings that take up the entire movie. Beginning is not measurable, but it is definite—it has precise coordinates but these coordinates are aesthetic, not spatial or temporal.

When you begin to read a story—anything that has a narrator—some extra questions arise in your mind. What counts as an event in this story? Am I privy to a major event or an insignificant one? There are some traditional ways of doing this, such as mise-en-scène (scene setting). Aperture is the feeling of uncertainty as to the relative speeds and tempos of the story. How can we know yet? Speed and tempo are relative, and thus we need sequences of events to compare. Likewise, the birth of just one object simply is a distortion of the plenitude of things, however slight. Novelty is guaranteed in an OOO universe, since the arrival of a new thing puts other things out of kilter with one another, just as the addition of a new poem changes the poems that went before it. A new thing is a distortion of other things.

There are some tricks realist novelists use to begin stories, to evoke aperture. These tricks are worth exploring, because they tell us something about how causality functions. Consider the beginning of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray:

The studio was filled with the rich odour of roses, and when the light summer wind stirred amidst the trees of the garden, there came through the open door the heavy scent of the lilac, or the more delicate perfume of the pink-flowering thorn.

From the corner of the divan of Persian saddle-bags on which he was lying, smoking, as was his custom, innumerable cigarettes, Lord Henry Wotton could just catch the gleam of the honey-sweet and honey-coloured blossoms of a laburnum, whose tremulous branches seemed hardly able to bear the burden of a beauty so flamelike as theirs; and now and then the fantastic shadows of birds in flight flitted across the long tussore-silk curtains that were stretched in front of the huge window, producing a kind of momentary Japanese effect, and making him think of those pallid, jade-faced painters of Tokyo who, through the medium of an art that is necessarily immobile, seek to convey the sense of swiftness and motion. [20]

“The studio…” [21] With his genius for minimalism, Wilde begins the story with a definite article. There is already a studio. Which studio? Huh? Right. That’s the feeling of beginning, aperture. To say The studio is to reference a studio that somehow preexists the narrative in which it appears. Imagine how it would feel if Wilde had begun his story with “A studio…” We would feel somehow “outside” of the story. We would feel in control. Instead, we find ourselves thrown into an ongoing situation. There is already at least one object. This is precisely the “feeling” of aperture. If we were to give it a name, I would call it “plus one,” borrowing a term from Alain Badiou: by adding to the plenum of objects, the “plus one” object disturbs the universe.

There is a more traditional way of starting a story: “Once upon a time there was a studio…” The opening phrase leads us gently into the narrative realm. The realist use of the definite article, on the other hand, rudely awakens us in medias res as Horace puts it. [22] And isn’t that how objects begin? Isn’t the compelling power of the story itself an echo of real objects, objects that subtend their availability-as, their use-as, their perception-as? Objects that preexist their as-structure? The beginning of an object is distortion. Other objects, like readers of a realist narrative, just find themselves in their midst, all of a sudden, in the realm of the plus-one. For this reason, any sense of neat wholeness is imposed on the plenum of objects arbitrarily.

Our analysis of narrative is by no means a superficial glimpse of some trivial fact pertaining to human constructs. Rather, the always-already quality of aperture has ontological implications. Watching a video of the shattering glass, played back ultra-slowly, we will never be able to specify exactly when the glass becomes its pieces. We confront a Sorites paradox not unlike the problem of the fragmenting table in the Introduction. We are only able to posit the existence of glass fragments retroactively. The fragmenting glass does not fragment in some neutral container of time. The glass pieces create their own time, their own temporal vortex that radiates out from them to any object in the vicinity that cares to be affected. An entirely new object is born, an alien entity as far as the rest of reality goes: a sliver of glass traveling at high speed through the air. There are fragments of glass; the studio… The plenum of objects is illuminated by the plus-one object: the plenum as plenum is never a stable bounded whole. The plenum is 1+n, an indeterminately vast array of objects whose overall impression is of an anarchic crowd of leering strangers, like characters in a painting by James Ensor.

Emmanuel Levinas is the great philosopher of the infinite against the totalizing: of the way just one entity, the real other, the stranger, undermines the coherence of my so-called world. Yet Levinas is also the great philosopher of the “there is,” the il y a. [23] With hauntingly evocative prose, Levinas describes the there is as resembling the night revealed to an insomniac, a creepy sense of being surrounded, not by nothing but by sheer existence. Now this there is is somewhat inadequate as far as OOO goes. The there is is only ever a vague elemental “splashing” or “rumbling,” an inchoate environmentality that seems to envelop you. This vagueness makes Levinas’s idea quite different from the fresh specificity that hits you in the arm with its glassy shards, making you bleed; or the studio that seems to be exuding its seductive pull on all the phenomena that encompass it and dwell in it—garden, birds, curtains, dilettantes, paintings, sofas and London.

Nonetheless, the there is works somewhat for us in describing the effect of aperture. Surely this is why Coleridge begins his masterpiece The Rime of the Ancient Mariner with “It is an Ancient Mariner…” (line 1). [24] Suddenly, there he is, foul breathed, crusty, oppressively abject, lurking like a homeless person at the entrance to the church. The there is is not a vague soup but a shatteringly specific object. Levinas writes, “The one affected by the other is an anarchic trauma.” [25] It’s so specific, it has no name (yet); it’s totally unique, it’s a kind of Messiah that breaks through the “homogeneous empty time” of sheer repetition that constitutes everyday reality. [26] The breakthrough of the plus-one shatters the coherence of the universe. Likewise, the idea that history is taking place within a tube of time is what Heidegger calls a “vulgar illusion.” [27] Revolutions strip this illusion bare.

Sublime Beginnings

If we want a term to describe the aesthetics of beginning, we could do worse than use the term sublime. The kind of sublime we need doesn’t come from some beyond, because this beyond turns out to be a kind of optical illusion of correlationism, the reduction of meaningfulness to the human–world correlate since Kant. OOO can’t think a beyond, since there’s nothing underneath the Universe of objects. Or not even nothing, if you prefer thinking it that way. The sublime resides in particularity, not in some distant beyond. And the sublime is generalizable to all objects, insofar as they are all strange strangers, that is, alien to themselves and to one another in an irreducible way. [28]

Of the two dominant theories of the sublime, we have a choice between authority and freedom, between exteriority and interiority. But both choices are correlationist. That is, both theories of the sublime have to do with human subjective access to objects. On the one hand we have Edmund Burke, for whom the sublime is shock and awe: an experience of terrifying authority to which you must submit. [29] On the other hand, we have Immanuel Kant, for whom the sublime is an experience of inner freedom based on some kind of temporary cognitive failure. Try counting up to infinity. You can’t. But that is precisely what infinity is. The power of your mind is revealed in its failure to sum infinity. [30]

Both sublimes assume that: (1) the world is specially or uniquely accessible to humans; (2) the sublime uniquely correlates the world to humans; and (3) what is important about the sublime is a reaction in the subject. The Burkean sublime is simply craven cowering in the presence of authority: the law, the might of a tyrant God, the power of kings, the threat of execution. No real knowledge of the authority is assumed—terrified ignorance will do. Burke argues outright that the sublime is always a safe pain, mediated by the glass panels of the aesthetic. That’s why horror movies, a truly speculative genre, try to bust through this aesthetic screen at every opportunity.

What we need is a more speculative sublime that actually tries to become intimate with the other, and here Kant is at any rate preferable to Burke. There is indeed an echo of reality in the Kantian sublime. Certainly the aesthetic dimension was a way in which the normal subject–object dichotomy is suspended in Kant. And the sublime is as it were the essential subroutine of the aesthetic experience, allowing us to experience the power of our mind by running up against some external obstacle. Kant references telescopes and microscopes that expand human perception beyond its limits. [31] His marvelous passage on the way one’s mind can encompass human height and by simple multiplication comprehend the vastness of “Milky Way systems” is sublimely expansive of the human capacity to think. [32] It’s also true that the Kantian sublime inspired the powerful speculations of Schelling, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, and more work needs to be done teasing out how those philosophers begin to think a reality beyond the human (the work of Iain Hamilton Grant and Ben Woodard stands out in particular at present). [33] It’s true that in §28 of the Third Critique, Kant does talk about how we experience the “dynamical sublime” in the terror of vastness, for instance of the ocean or the sky. But this isn’t anything like intimacy with the sky or the ocean.

In subsequent sections, Kant in fact explicitly rules out anything like a scientific or even probing analysis of what might exist in the sky. As soon as we think of the ocean as a body of water containing fish and whales, rather than as a canvas for our psyche; as soon as we think of the sky as the real Universe of stars and black holes, we aren’t experiencing the sublime (§29):

While we may share Kant’s anxiety about teleology, his main point is less than satisfactory from a speculative realist point of view. We positively shouldn’t speculate when we experience the sublime. The sublime is precisely the lack of speculation. Should we then just throw in the towel and drop the sublime altogether, choosing only to go with horror—the limit experience of sentient lifeforms—rather than the sublime, as several speculative realists have done? Can we only speculate from and into a position of feeling our own skin about to shred, or vomit about to exit from our lungs?

Yet horror presupposes the proximity of at least one other entity: a lethal virus, an exploding hydrogen bomb, an approaching tsunami. Intimacy is thus a precondition of horror. From this standpoint, even horror is too much of a reaction shot, too much about how entities correlate with an observer. What we require is something deeper, that subtends the Kantian sublime. What we require, then, is an aesthetic experience of coexisting with 1+n other entities, living or nonliving. What speculative realism needs would be a sublime that grants a kind of intimacy with real entities. This is precisely the kind of intimacy prohibited by Kant, in which the sublime requires a Goldilocks aesthetic distance, not too close and not too far away (§25):

The Kantian aesthetic dimension shrink-wraps objects in a protective film. Safe from the threat of radical intimacy, the inner space of Kantian freedom develops unhindered. Good taste is knowing precisely when to vomit—when to expel any foreign substance perceived to be disgusting and therefore toxic. [36] This won’t do in an ecological era in which “away”—the precondition for vomiting—no longer exists. Our vomit just floats around somewhere near us, since there is now no “away” to which we can flush it in good faith.

Against the correlationist sublime I shall now argue for a speculative sublime, an object-oriented sublime to be more precise. There is a model for just such a sublime on the market—the oldest extant text on the sublime, Peri Hypsous by Longinus. The Longinian sublime is about the physical intrusion of an alien presence. The Longinian sublime can thus easily extend to include non-human entities—and indeed non-sentient ones. Rather than making ontic distinctions between what is and what isn’t sublime, Longinus describes how to achieve sublimity. Because he is more interested in how to achieve the effect of sublimity rhetorically than what the sublime is as a human experience, Longinus leaves us free to extrapolate all kinds of sublime events between all kinds of entities.

Longinus’ sublime is already concerned with an object-like alien presence—he might call it God but we could easily call it a Styrofoam peanut or the Great Red Spot of Jupiter. The way objects appear to one another is sublime: it’s a matter of contact with alien presence, and a subsequent work of radical translation. Longinus thinks this as contact with another: “Sublimity is the echo of a noble mind.” [37] Echo, mind—it’s as if the mind were not an ethereal ghost but a solid substance that ricochets off walls. We could extend this to include the sensuality of objects. Why not? So many supposedly mental phenomena manifest in an automatic way, as if they were objects: dreams, hallucinations, strong emotions. Coleridge says about his opium dream that inspired Kubla Khan that the images arose as distinct things in his mind. This isn’t surprising if cognition is an assemblage of kluge-like unit operations (Ian Bogost’s term) that just sort of do their thing. It’s not that this pen is alive. It’s that everything that is meaningful about my mind resting on the pen can also be said of the pen resting on the desk. Consciousness may be sought after in the wrong place by neuroscientists and AI (and anti-AI) theorists: it may be incredibly default. Mind may simply be an interobjective phenomenon among many: a distributed mind that consists of neurons, desks, cooking utensils, children and trees. [38]

Let’s consider Longinus’ terms. Luckily for OOO there are four of them: transport, phantasia, clarity and brilliance. Even more luckily, the four correspond to Harman’s interpretation of the Heideggerian fourfold (Earth, Heaven, Gods, Mortals) as a set of descriptions of the basic properties of objects. The trick is to read Longinus’ terms in reverse, as we did with rhetoric in general. The first two terms, clarity and brilliance, refer to the actuality of object–object encounters. The second two, transport and phantasia, refer to the appearance of these encounters. It sounds counter-intuitive that brilliance would equate to withdrawal, but on a reading of what Plato, Longinus and Heidegger have to say about this term (ekphanestaton) more clarity will be reached.

- Brilliance. Earth. Objects as secret “something at all,” apart from access.

- Clarity: Gods. Objects as specific, apart from access.

- Transport: Mortals. Objects as something-at-all for another object.

- Phantasia: Heaven. Objects as specific appearance to another object. [39]

Each one sets up relationships with an alien presence.

(1) Brilliance. In Greek, to ekphanestaton, luster, brilliance, shining-out. Ekphanestaton is a superlative, so it really means “the most brilliant,” “eminent brilliance.” This eminence must mean prior to all relations. Longinus declares that “in much the same way as dim lights vanish in the radiance of the sun, so does the all-pervading effluence of grandeur utterly obscure the artifice of rhetoric.” [40] Brilliance is what hides objects. Brilliance is the secretiveness of the object, its total inaccessibility prior to relations. In the mode of the sublime, it’s as if we are able to taste that, even though it’s strictly impossible. The light of this inner magma is blinding—that’s why it’s withdrawal, strangely. It’s right there, it’s an actual object. Longinus thus calls this brilliance an uncanny fact of the sublime.

For Plato to ekphanestaton was an index of the essential beyond. For the object-oriented ontologist, brilliance is the appearance of the object in all its stark unity. Something is coming through. Or better: we realize that something was already there. This is the realm of the uncanny, the strangely familiar and familiarly strange.

(2) Clarity (enargeia). “Manifestation,” “self-evidence.” This has to do with ekphrasis. [41] Ekphrasis in itself is interesting for OOO, because ekphrasis is precisely an object-like entity that looms out of descriptive prose. It’s a hyper-descriptive part that jumps out at the reader, petrifying her or him (turning him to stone), causing a strange suspension of time like Bullet Time in The Matrix. It’s a little bit like what Deleuze means when he talks about “time crystals” in his study of cinema. [42] This is the jumping-out aspect of ekphrasis, a bristling vividness that interrupts the flow of the narrative, jerking the reader out of her or his complacency. Quintilian stresses the time-warping aspect of enargeia (the term is metastasis or metathesis), transporting us in time as if the object had its own gravitational field into which it sucks us. The object in its bristling specificity.

Longinus asserts that while sublime rhetoric must contain enargeia, sublime poetry must evoke ekplexis—astonishment. [43] This may also be seen as a kind of specific impact. In strictly OOO terms, ekphrasis is a translation that inevitably misses the secretive object, but which generates its own kind of object in the process. Ekphrasis speaks to how objects move and have agency, despite our awareness or lack of awareness of them; Harman’s analogy of the drugged man in Tool-Being provides a compelling example. [44] Now if somehow you get it wrong, you end up with bombast: the limit where objects become vague, undefined, just clutter (the word bombast literally means “stuffing,” the kind found in shoulder pads).

(3) Transport. The narrator makes you feel something stirring inside you, some kind of divine or demonic energy, as if you were inhabited by an alien. “Being moved,” “being stirred.” [45] We can imagine the sublime as a kind of transporter, like in Star Trek, a device for beaming the alien object into another object’s frame of reference. Transport consists of sensual contact with objects as an alien universe. Just as the transporter can only work by translating particles from one place to another, so Longinian transport only works by one object translating another via its specific frames of reference. In so doing, we become aware of what was lost in translation. Transport thus depends upon something much richer than a void: the open secret reality of the universe of objects, the aspect that is forever sealed from access but nevertheless thinkable.

The machinery of transport, the transporter as such, is what Longinus calls amplification: not bigness but a feeling of (as Doctor Seuss puts it) “biggering”: “[a figure] employed when the matters under discussion or the points of an argument allow of many pauses and many fresh starts from section to section, and the grand phrase come rolling out one after another with increasing effect”; in this way Plato, for instance, “often swells into a mighty expanse of grandeur.” [46] By attuning our mind to the exploding notes of an object, amplification sets up a sort of subject-quake, a soul-quake.

(4) Phantasia. Often translated as “visualization.” [47] Visualization not imagery: producing an inner object. It’s imagery in you not in the text. Quintilian remarks that phantasia makes absent things appear to be present. [48] Phantasia conjures an object. If I say “New York” and you’re a New Yorker, you don’t have to tediously picture each separate building and street. You sort of evoke New Yorkness in your mind. That’s phantasia. What I’ve called the poetics of spice operates this way: the use of the word “spice” (rather than say cinnamon or pepper) in a poem acts as a blank allowing for the work of olfactory imagination akin to visualization. [49] It’s more like a hallucination than an intended thought. [50] In stories, for instance, phantasia generates an object-like entity that separates us from the narrative flow—puts us in touch with the alien as alien. Visualization should be slightly scary: you are summoning a real deity after all, you are asking to be overwhelmed, touched, moved, stirred.

The suddenness of an alien appearance in my phenomenal space is an apparition. In OOO terms, phantasia is the capacity of an object to imagine another object. This depends upon a certain sensual contact. How paper looks to stone. How scissors look to paper. Do objects dream? Do they contain virtual versions of other objects inside them? These would be examples of phantasia. How one object impinges upon another one. There is too much of it. It magnetizes us with a terrible compulsion.

We should briefly recap what we now know about the Longinian sublime. Longinus says that sublimity is “the echo of a noble mind.” There isn’t much difference between human souls, if they exist, and the souls of badgers, ferns, and seashells. The Longinian sublime is based on coexistence. At least one other thing exists, apart from me: that “noble mind,” whose footprint I find in my inner space. By contrast, the more familiar concepts of the sublime are based on the experience of just one person. It’s my fear and terror, my shock and awe (Burke). It’s my freedom, my infinite inner space (Kant). Of course, some object triggers the sublime. But then you drop the trigger and just focus on the state: this is especially true in Kant. And Burke is just about oppression. It’s about the power of kings and bombing raids. Why couldn’t the sublime object be something vulnerable or kind?

Let’s think again about how causality is aesthetic. The sublime, on this view, is how fresh objects are born. Suddenly, other objects discover these shards of glass in their world, fragments of broken object embedded in their flesh, scattered over the floor. It’s not so much that Burke and Kant are wrong, but that what they’re thinking is ontologically secondary to the notion of coexistence. Longinus puts the sublime a way back in the causal sequence, in the “noble” being that leaves its footprint on you. In this sense, it’s in the object, in the not-me. Thus the sublime tunes us to what is not me. This is good news in an ecological era. Before it’s fear or freedom, the sublime is coexistence.

Now for an example of the Longinian sublime, take Harman’s first great use of the “meanwhile” trope (which Quentin Meillassoux calls the rich elsewhere), in his paper “Object-Oriented Philosophy”:

But beneath this ceaseless argument, reality is churning. Even as the philosophy of language and its supposedly reactionary opponents both declare victory, the arena of the world is packed with diverse objects, their forces unleashed and mostly unloved. Red billiard ball smacks green billiard ball. Snowflakes glitter in the light that cruelly annihilates them; damaged submarines rust along the ocean floor. As flour emerges from mills and blocks of limestone are compressed by earthquakes, gigantic mushrooms spread in the Michigan forest. While human philosophers bludgeon each other over the very possibility of “access” to the world, sharks bludgeon tuna fish and icebergs smash into coastlines.

All of these entities roam across the cosmos, inflicting blessings and punishments on everything they touch, perishing without a trace or spreading their powers further—as if a million animals had broken free from a zoo in some Tibetan cosmology… [51]

This is nobody’s world. This is sort of the opposite of stock-in-trade environmentalist rhetoric (which elsewhere I’ve called ecomimesis): “Here I am in this beautiful desert, and I can prove to you I’m here because I can write that I see a red snake disappearing into that creosote bush. Did I tell you I was in a desert? That’s me, here, in a desert. I’m in a desert.” [52] This is no man’s land. But it’s not a bleak void. Bleak void, it turns out, is just the flip side of correlationism’s world. No. This is a crowded Tibetan zoo, an Expressionist parade of uncanny, clownlike objects. We’re not supposed to kowtow to these objects as Burke would wish. Yet we’re not supposed to find our inner freedom either (Kant). It’s like one of those maps with the little red arrow that says You Are Here, only this one says You Are Not Here.

Novelty versus Emergence

Now realize that the novelty of aperture is true for every object, not simply for sentient beings and certainly not simply for humans. A kettle begins to boil. Water in the kettle starts to seethe and give off steam. At a subatomic level, electrons are quantum jumping to more distant orbits around the nuclei of atoms. For an atom that is not yet in an excited state, nothing is happening. It’s only from the point of view of at least one other “observer,” say a measuring device like me or like the whistle at the top of the kettle, that the kettle is boiling smoothly. At another level altogether, there are a series of sudden jumps, none of which on its own is the thing we call boiling.

This is the big problem with the now popular notion of emergence. The problem is that emergence fails to explain how things begin, because emergence is always emergence-for. Emergence requires at least one object outside the system that is perceived as emergent. Something must already be in existence for emergence to happen. That is to say, emergent properties are sensual in OOO terms. Emergent things are manifestations of appearance-as or appearance-for, what Harman calls the as-structure. Emergence requires a holistic system in which the whole is always greater than its parts—otherwise, runs the argument, nothing could emerge from anything. But in an OOO reality, the parts always outnumber the whole. What happens when objects begin is that more parts suddenly appear, breaking away from objects that seemed like stable entities. These parts are without wholes, like limbs in some horror movie, flailing around in the void. It’s only later that we can posit some whole from which they “emerge.”

All the classical definitions of emergence seem to indicate that they are talking about wholes that are more than the sum of their parts, that are relatively stable, that exert downward causality (they can affect their parts), and so on. Current ontological ideology, fixated on process, assumes that emergence is some kind of basic machinery that keeps the world together and generates new parts of the world. The tendency is to see it as some kind of underlying causal mechanism by which smaller components start to function as a larger, super component. If true, this would seriously upset the object-oriented applecart. Why? Because objects are the ontologically primary entities. In an OOO reality, emergence must be a property of objects, not the other way around. In other words, emergence is always sensual.

Emergence implies 1+n objects interacting in what Harman calls the sensual ether. [53] This ether is the causal machinery, not some underlying wires and pulleys. Let’s now consider how emergence is really a sensual property of objects. Let’s consider an easier kind of emergence—that is, a kind about which it’s easier to say that it’s sensual, produced in interactions with other entities. There are numerous illustrations of emergence in visual perception.

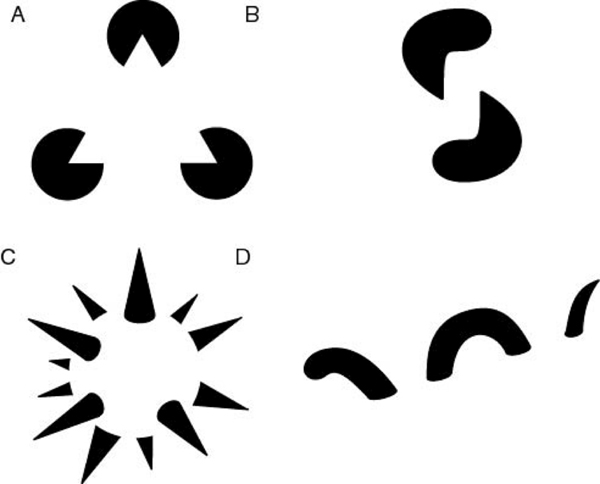

Pop! A sphere, a triangle, a Loch Ness Monster emerge from the patterns of black on white. According to the theory you don't assemble the forms out of their parts. They emerge out of the fragments of shading and blank space in the picture. Now this kind of emergence clearly requires an observer. It requires, more minimally, an interaction between the image and some other entity. If “observer” sounds too much like a (human) subject, then try this neuroscientific explanation of how it works:

“[F]orm emerges from the parallel action of innumerable local forces … acting in unison.” What does that mean? It means that emergence is a sensual object. Emergence is relational. Snowflakes, for instance, form in interactions between water crystals and properties of the ambient air through which they fall (temperature, humidity). It would be truly strange if snowflakes magically assembled themselves out of themselves alone, without interactions with anything else. This would mean that there was some kind of mysterious engine of causality working underneath or within them. This kind of deep emergence should strike us as slightly odd—how can something build itself?

No wonder we have trouble thinking of minds. How come patterns of neurons just pop into mentation? However, if emergence is a sensual object produced by neurons plus other entities in their vicinity, there is no problem. There’s no need, Harman argues, to see any difference between what my chair does to the floor (which prevents me “from plummeting 30 meters to the cellar” as he puts it memorably), and what my mind does to the floor. [55] That is to say, my chair relies on but also ignores the floor to a large extent, just as my mind does. This is not to claim that chairs are mind-like, but the reverse. Ontologically a mind is like a chair sitting on the floor. The chair rough-hews a chunk of floorness for its distinct nefarious purposes, and so does a mind. We might predict then that “mind” is not some special bonus prize for being highly developed. Which is not to say that what human minds do is exactly the same as what chairs do in every specific. “Mind” is an emergent property of a brain, perhaps, but not all that amazingly different from emergent properties of chairs on floors. And mind requires not simply a brain, but all kinds of objects that become enmeshed with the brain, from eggs to frying pans to credit card bills.

Reality really would be strange if there were some magical property hidden beneath objects. All we need for object-oriented magic, however, are objects. Their interaction generates a sensual ether in which the magic takes place. The best place to do magic is right under your nose. No one can believe it when it’s in your face. You suspect some hidden mystery. But as Poe’s story “The Purloined Letter” makes clear, the real mystery is in your face.

The anxiety about form and formal causation in modern science and philosophy is probably what gives rise to the mystery and slight fascination or dread surrounding notions of emergence. Somehow we want causation to be clunky, to involve materialities bonking into one another like the proverbial metal balls in the proverbial executive toy. But if causality happens because of shape (as well as, or even instead of, because of matter) then we are forced to consider all kinds of things that materialist science, since its inception, has had trouble with (such as epigenesis). Formal causes are precisely the black sheep of science, marked with a big scarlet letter (S for Scholastic).

Emergence steps in as a kind of magic grease to oil the engine presumed to lurk in the sub-basement of reality beneath objects. Yet emergence is always emergence-for or emergence-as (somewhat the same thing). Consider again the case of the boiling kettle. What is happening? Electrons are quantum jumping from lower to higher orbits. This behavior, a phase transition, emerges as boiling for an observer like me, waiting for my afternoon tea. The smooth, holistic slide of water from cool to boiling happens to me, an observer, just like the way the sphere pops out of the patches of black in Figure 1. Emergence appears unified and smooth, but this holistic event is always for-another-entity. It would be wrong to say that the water has emergent properties of boiling that somehow “come out” at the right point. It’s less mysterious to say that when the heating element on my stove interacts with the water, it boils. Its emergence-as-boiling is a sensual object, produced in an interaction between kettle and stove.

Likewise, on this view, mind is not to be found “in” neurons, but in sensual interactions between neurons and other objects. There is some truth, then, in the esoteric Buddhist idea that mind is not to be found “in” your body—nor is it to be found “outside” it, nor “somewhere in between,” as the saying goes. There is far less mystery in this view, but perhaps there is a lot of magic. The ordinary world in which kettles boil and minds think about tea is an entangled mesh where it becomes impossible to say where one (sensual) object starts and another (sensual) object stops.

Now the preexistence of 1+n objects tells us something about how to think origins. I’m not particularly interested in answering whether the universe is created by a god or not. As far as I’m concerned there could be an infinite temporal regress of physical events. But we can lay down some ground rules for how a god should operate in an object-oriented reality. A god would need at least one other entity in order to re-mark his or her existence. Until the universe was created, there could be no god, in particular. It is simply impossible to designate one being as a causa sui (as the scholastics put it) that stands in a privileged relation to all the others.

I use the term re-mark after Jacques Derrida’s analysis of how paintings differ (or not) from written texts. How can you tell that a squiggle is a letter and not just a dash of paint? [56] This is a genuine problem. You enter a classroom. The blackboard is scrawled with writing. But as you come closer, you see that the writing is actually not writing at all, but the half-erased chalk marks that may or may not have been writing at some point.

Any mark, argues Derrida, depends upon at least one other thing (there’s that pesky 1+n again). This could be as simple as an inscribable surface, or a system of what counts as a meaningful mark. For there to be a difference that makes a difference there must be at least one other object that the mark can’t explain, re-marking the mark. Marks can’t make themselves mean all by themselves. If they could, then meaning could indeed be reduced to a pure structuralist system of relations. Since they can’t, then the “first mark” is always going to be uncertain, in particular because it’s strictly secondary to the inscribable surface (or whatever) on which it takes places. There must be some aperture at the beginning of any system, in order for it to be a system—some irreducible uncertainty. Some kind of magic, some kind of illusion that may or may not be the beginning of something.

The idea of an inscribable surface is not an abstract one. A game could be thought of as an interobjective space consisting of a number of different agents, such as boards, pieces, players and rules. [57] This space depends upon 1+n withdrawn objects for its existence. A game is a symptom of real coexisting objects. Citing Kenneth Burke and Gregory Bateson, Brian Sutton-Smith made a similar suggestion about the function of play biting in animals. He suggested that play might be the earliest form of a negative, prior to the existence of the negative in language. Play, as a way of not doing whatever it represents, prevents error. It is a positive behavioral negative. It says no by saying yes. It is a bite but it is a nip. [58] In both cases, the urge to play is a means of communicating in a situation in which intelligent creatures have not yet acquired language. A play action is a signal similar to a predator call, except that its referent is to the social world. If you’ve ever owned a kitten you will see that play biting goes quite far down and quite far in to mammalian ontogeny. Think about what this means. It means for a kick off that what we call language is a small part of a much bigger configuration space. For a word to be a play-bite, a play-bite must already refer to a genuine bite. There has to exist an interobjective space in which “meaning” can take place. The fact that we speak, then, means not that we are different from animals, but that we encapsulate a vast array of nonhuman entities and behaviors. For language to exist at all, there have to be all kinds of objects already in play. All kinds of inscribable surfaces.

Again we encounter some thoughts about the nature of mind. Consider Andy Clark’s and David Chalmers’s essay “The Extended Mind.” [59] The argument is remarkably akin to some implications of Derrida’s essay “Plato’s Pharmacy.” Not that Derrida spells them out—he studiously avoids talking about what is, a sin of omission. But Derrida does argue that there’s no sense in which some notional internal memory can be said to be better than external devices such as wax tablets and flash drives. [60] Or more real, or more intrinsic to “what it means to be human,” and so on.

Clark and Chalmers seem to echo this when they argue that the idea that cognition happens “inside” the brain is only a prejudice. The best parts of deconstruction, for me, are those parts that refute relationism. It’s structuralism that is purely relationist. Deconstruction constantly points out that meaningfulness depends upon 1+n entities that are excluded from the system, yet included by being excluded, thus undermining the system’s coherence. These entities can include wax tablets, ink and paper. Whether or not they are “signifiers” is precisely at issue. Meaning arises from the meaningless. It’s not relations all the way down.

There is no such thing as meaning in a void, which is why I prefer Derrida’s re-mark to Spencer-Brown’s roughly contemporaneous Mark. [61] Spencer-Brown’s Mark seems to create itself and its conditions for interpretation out of a void, like some proud Hindu or Judaeo-Christian god. Yet there must already be an inscribable surface on which the Mark appears. Marks require a stage on which to strut their stuff. This is the preferred sense in which I take Derrida’s term arche-writing. Not “everything is signs all the way down”—but everything isn’t.

Perhaps this is letting Derrida off the hook too easily, since it’s quite possible to use his work to underwrite anti-realism, as many have. Yet there is a kind of givenness in Derrida, despite his statements to the contrary. He calls it arche-writing, trace, différance, gramma. By contrast, the Mark pretends to be a magic wand or a magic word like Abracadabra. Reality is like an illusion—you never know. The way objects appear is like magic. If reality were actually, definitely, verifiably magic, we would be in a world designed by a theist or by a nihilist (take your pick). It’s time for that quotation again: “What constitutes pretense is that, in the end, you don’t know whether it’s pretense or not.” [62]

Spencer-Brown style theories lead to what is now called emergence. Emergentism wants to catch novelty in the act of its appearance. If that doesn’t sound like an impossible task right now, I may not have written this book carefully enough. For something to happen, it must happen twice. An object is always already inside some other object, like writing appearing on a piece of paper. Furthermore, emergence per se is emergence-for. There is at least one “observer”—naturally this observer need not be human or even traditionally sentient. When excited noble gases emerge as photons in a fluorescent lamp, they emerge-for the bathroom off of whose walls the photons reflect. When a cloud of dusty spores emerges as moldy peach rots in a forgotten bowl, the dust emerges-for the currents of air in the deserted kitchen. When a kettle boils unseen, the steam emerges-for the less excited particles in the water on the stove and for the framed photograph on the windowsill, whose glass it coats with a fine layer of mist.

We can trace some of the problems of certain forms of materialism to a fixation on emergence as an ontotheological fact: in this case, emergence is taken not to be emergence-for, but to operate all by itself, a kind of causal miracle. Consider the Marxist theory of the emergence of industrial capitalism. From this standpoint, it turns out that the real problem with Marxism is that Marx is an idealist, or perhaps a correlationist. How can one justify such a fanciful notion? As a matter of fact, there are plenty of ways to do this. For instance we could look at Marx’s antiquated anthropocentrism, which his beloved Darwin had blown sky high by the time he put pen to paper. But my argument here is more technical, and pertains to the issue at hand: how do things appear?

Consider chapter 15 of Capital 1. There Marx outlines his theory of machines. The basic argument is that when you have enough machines that make other machines, you get a qualitative leap into full-on industrial capitalism. Marx never specifies how many machines this takes. You know it when you see it. If it looks like industrial capitalism, and quacks like industrial capitalism, then... So what this boils down to is a theory of emergence. Capitalism proper emerges from its commercial phase when there are enough machines going ker-plunk or whatever. This is highly reminiscent of the Turing Test. [63] Intelligence is an emergent property of enough algorithms doing their thing, runs the theory. The point is, emergent for whom? If I’m sitting on the other side of the two rooms, and I receive some printouts from each room that look fairly similar, and make me think that an intelligent person is behind the door, then an intelligent person is behind the door. For a theory that tries to explain the whole of social space, this is a significant problem.

That’s the trouble with emergentism. Any system requires 1+n entities external to it for it to exist and to be measured, and so on. This is Derrida’s wonderful conclusion about structuralism. Deconstruction is often confused with structuralism—but it’s the latter that says that nothing really means anything, it’s all relational. What deconstruction argues is that for any system of meaning, there is at least one opaque entity that the system can’t assimilate, which it must simultaneously include and exclude in order to exist.