Novelty versus Emergence

Now realize that the novelty of aperture is true for every object, not simply for sentient beings and certainly not simply for humans. A kettle begins to boil. Water in the kettle starts to seethe and give off steam. At a subatomic level, electrons are quantum jumping to more distant orbits around the nuclei of atoms. For an atom that is not yet in an excited state, nothing is happening. It’s only from the point of view of at least one other “observer,” say a measuring device like me or like the whistle at the top of the kettle, that the kettle is boiling smoothly. At another level altogether, there are a series of sudden jumps, none of which on its own is the thing we call boiling.

This is the big problem with the now popular notion of emergence. The problem is that emergence fails to explain how things begin, because emergence is always emergence-for. Emergence requires at least one object outside the system that is perceived as emergent. Something must already be in existence for emergence to happen. That is to say, emergent properties are sensual in OOO terms. Emergent things are manifestations of appearance-as or appearance-for, what Harman calls the as-structure. Emergence requires a holistic system in which the whole is always greater than its parts—otherwise, runs the argument, nothing could emerge from anything. But in an OOO reality, the parts always outnumber the whole. What happens when objects begin is that more parts suddenly appear, breaking away from objects that seemed like stable entities. These parts are without wholes, like limbs in some horror movie, flailing around in the void. It’s only later that we can posit some whole from which they “emerge.”

All the classical definitions of emergence seem to indicate that they are talking about wholes that are more than the sum of their parts, that are relatively stable, that exert downward causality (they can affect their parts), and so on. Current ontological ideology, fixated on process, assumes that emergence is some kind of basic machinery that keeps the world together and generates new parts of the world. The tendency is to see it as some kind of underlying causal mechanism by which smaller components start to function as a larger, super component. If true, this would seriously upset the object-oriented applecart. Why? Because objects are the ontologically primary entities. In an OOO reality, emergence must be a property of objects, not the other way around. In other words, emergence is always sensual.

Emergence implies 1+n objects interacting in what Harman calls the sensual ether. [53] This ether is the causal machinery, not some underlying wires and pulleys. Let’s now consider how emergence is really a sensual property of objects. Let’s consider an easier kind of emergence—that is, a kind about which it’s easier to say that it’s sensual, produced in interactions with other entities. There are numerous illustrations of emergence in visual perception.

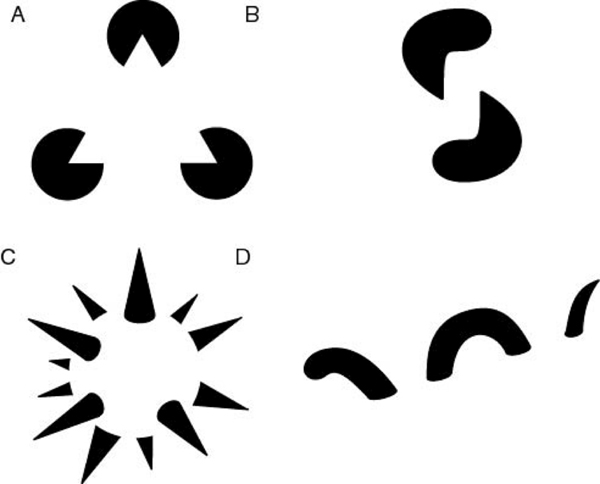

Pop! A sphere, a triangle, a Loch Ness Monster emerge from the patterns of black on white. According to the theory you don't assemble the forms out of their parts. They emerge out of the fragments of shading and blank space in the picture. Now this kind of emergence clearly requires an observer. It requires, more minimally, an interaction between the image and some other entity. If “observer” sounds too much like a (human) subject, then try this neuroscientific explanation of how it works:

“[F]orm emerges from the parallel action of innumerable local forces … acting in unison.” What does that mean? It means that emergence is a sensual object. Emergence is relational. Snowflakes, for instance, form in interactions between water crystals and properties of the ambient air through which they fall (temperature, humidity). It would be truly strange if snowflakes magically assembled themselves out of themselves alone, without interactions with anything else. This would mean that there was some kind of mysterious engine of causality working underneath or within them. This kind of deep emergence should strike us as slightly odd—how can something build itself?

No wonder we have trouble thinking of minds. How come patterns of neurons just pop into mentation? However, if emergence is a sensual object produced by neurons plus other entities in their vicinity, there is no problem. There’s no need, Harman argues, to see any difference between what my chair does to the floor (which prevents me “from plummeting 30 meters to the cellar” as he puts it memorably), and what my mind does to the floor. [55] That is to say, my chair relies on but also ignores the floor to a large extent, just as my mind does. This is not to claim that chairs are mind-like, but the reverse. Ontologically a mind is like a chair sitting on the floor. The chair rough-hews a chunk of floorness for its distinct nefarious purposes, and so does a mind. We might predict then that “mind” is not some special bonus prize for being highly developed. Which is not to say that what human minds do is exactly the same as what chairs do in every specific. “Mind” is an emergent property of a brain, perhaps, but not all that amazingly different from emergent properties of chairs on floors. And mind requires not simply a brain, but all kinds of objects that become enmeshed with the brain, from eggs to frying pans to credit card bills.

Reality really would be strange if there were some magical property hidden beneath objects. All we need for object-oriented magic, however, are objects. Their interaction generates a sensual ether in which the magic takes place. The best place to do magic is right under your nose. No one can believe it when it’s in your face. You suspect some hidden mystery. But as Poe’s story “The Purloined Letter” makes clear, the real mystery is in your face.

The anxiety about form and formal causation in modern science and philosophy is probably what gives rise to the mystery and slight fascination or dread surrounding notions of emergence. Somehow we want causation to be clunky, to involve materialities bonking into one another like the proverbial metal balls in the proverbial executive toy. But if causality happens because of shape (as well as, or even instead of, because of matter) then we are forced to consider all kinds of things that materialist science, since its inception, has had trouble with (such as epigenesis). Formal causes are precisely the black sheep of science, marked with a big scarlet letter (S for Scholastic).

Emergence steps in as a kind of magic grease to oil the engine presumed to lurk in the sub-basement of reality beneath objects. Yet emergence is always emergence-for or emergence-as (somewhat the same thing). Consider again the case of the boiling kettle. What is happening? Electrons are quantum jumping from lower to higher orbits. This behavior, a phase transition, emerges as boiling for an observer like me, waiting for my afternoon tea. The smooth, holistic slide of water from cool to boiling happens to me, an observer, just like the way the sphere pops out of the patches of black in Figure 1. Emergence appears unified and smooth, but this holistic event is always for-another-entity. It would be wrong to say that the water has emergent properties of boiling that somehow “come out” at the right point. It’s less mysterious to say that when the heating element on my stove interacts with the water, it boils. Its emergence-as-boiling is a sensual object, produced in an interaction between kettle and stove.

Likewise, on this view, mind is not to be found “in” neurons, but in sensual interactions between neurons and other objects. There is some truth, then, in the esoteric Buddhist idea that mind is not to be found “in” your body—nor is it to be found “outside” it, nor “somewhere in between,” as the saying goes. There is far less mystery in this view, but perhaps there is a lot of magic. The ordinary world in which kettles boil and minds think about tea is an entangled mesh where it becomes impossible to say where one (sensual) object starts and another (sensual) object stops.

Now the preexistence of 1+n objects tells us something about how to think origins. I’m not particularly interested in answering whether the universe is created by a god or not. As far as I’m concerned there could be an infinite temporal regress of physical events. But we can lay down some ground rules for how a god should operate in an object-oriented reality. A god would need at least one other entity in order to re-mark his or her existence. Until the universe was created, there could be no god, in particular. It is simply impossible to designate one being as a causa sui (as the scholastics put it) that stands in a privileged relation to all the others.

I use the term re-mark after Jacques Derrida’s analysis of how paintings differ (or not) from written texts. How can you tell that a squiggle is a letter and not just a dash of paint? [56] This is a genuine problem. You enter a classroom. The blackboard is scrawled with writing. But as you come closer, you see that the writing is actually not writing at all, but the half-erased chalk marks that may or may not have been writing at some point.

Any mark, argues Derrida, depends upon at least one other thing (there’s that pesky 1+n again). This could be as simple as an inscribable surface, or a system of what counts as a meaningful mark. For there to be a difference that makes a difference there must be at least one other object that the mark can’t explain, re-marking the mark. Marks can’t make themselves mean all by themselves. If they could, then meaning could indeed be reduced to a pure structuralist system of relations. Since they can’t, then the “first mark” is always going to be uncertain, in particular because it’s strictly secondary to the inscribable surface (or whatever) on which it takes places. There must be some aperture at the beginning of any system, in order for it to be a system—some irreducible uncertainty. Some kind of magic, some kind of illusion that may or may not be the beginning of something.

The idea of an inscribable surface is not an abstract one. A game could be thought of as an interobjective space consisting of a number of different agents, such as boards, pieces, players and rules. [57] This space depends upon 1+n withdrawn objects for its existence. A game is a symptom of real coexisting objects. Citing Kenneth Burke and Gregory Bateson, Brian Sutton-Smith made a similar suggestion about the function of play biting in animals. He suggested that play might be the earliest form of a negative, prior to the existence of the negative in language. Play, as a way of not doing whatever it represents, prevents error. It is a positive behavioral negative. It says no by saying yes. It is a bite but it is a nip. [58] In both cases, the urge to play is a means of communicating in a situation in which intelligent creatures have not yet acquired language. A play action is a signal similar to a predator call, except that its referent is to the social world. If you’ve ever owned a kitten you will see that play biting goes quite far down and quite far in to mammalian ontogeny. Think about what this means. It means for a kick off that what we call language is a small part of a much bigger configuration space. For a word to be a play-bite, a play-bite must already refer to a genuine bite. There has to exist an interobjective space in which “meaning” can take place. The fact that we speak, then, means not that we are different from animals, but that we encapsulate a vast array of nonhuman entities and behaviors. For language to exist at all, there have to be all kinds of objects already in play. All kinds of inscribable surfaces.

Again we encounter some thoughts about the nature of mind. Consider Andy Clark’s and David Chalmers’s essay “The Extended Mind.” [59] The argument is remarkably akin to some implications of Derrida’s essay “Plato’s Pharmacy.” Not that Derrida spells them out—he studiously avoids talking about what is, a sin of omission. But Derrida does argue that there’s no sense in which some notional internal memory can be said to be better than external devices such as wax tablets and flash drives. [60] Or more real, or more intrinsic to “what it means to be human,” and so on.

Clark and Chalmers seem to echo this when they argue that the idea that cognition happens “inside” the brain is only a prejudice. The best parts of deconstruction, for me, are those parts that refute relationism. It’s structuralism that is purely relationist. Deconstruction constantly points out that meaningfulness depends upon 1+n entities that are excluded from the system, yet included by being excluded, thus undermining the system’s coherence. These entities can include wax tablets, ink and paper. Whether or not they are “signifiers” is precisely at issue. Meaning arises from the meaningless. It’s not relations all the way down.

There is no such thing as meaning in a void, which is why I prefer Derrida’s re-mark to Spencer-Brown’s roughly contemporaneous Mark. [61] Spencer-Brown’s Mark seems to create itself and its conditions for interpretation out of a void, like some proud Hindu or Judaeo-Christian god. Yet there must already be an inscribable surface on which the Mark appears. Marks require a stage on which to strut their stuff. This is the preferred sense in which I take Derrida’s term arche-writing. Not “everything is signs all the way down”—but everything isn’t.

Perhaps this is letting Derrida off the hook too easily, since it’s quite possible to use his work to underwrite anti-realism, as many have. Yet there is a kind of givenness in Derrida, despite his statements to the contrary. He calls it arche-writing, trace, différance, gramma. By contrast, the Mark pretends to be a magic wand or a magic word like Abracadabra. Reality is like an illusion—you never know. The way objects appear is like magic. If reality were actually, definitely, verifiably magic, we would be in a world designed by a theist or by a nihilist (take your pick). It’s time for that quotation again: “What constitutes pretense is that, in the end, you don’t know whether it’s pretense or not.” [62]

Spencer-Brown style theories lead to what is now called emergence. Emergentism wants to catch novelty in the act of its appearance. If that doesn’t sound like an impossible task right now, I may not have written this book carefully enough. For something to happen, it must happen twice. An object is always already inside some other object, like writing appearing on a piece of paper. Furthermore, emergence per se is emergence-for. There is at least one “observer”—naturally this observer need not be human or even traditionally sentient. When excited noble gases emerge as photons in a fluorescent lamp, they emerge-for the bathroom off of whose walls the photons reflect. When a cloud of dusty spores emerges as moldy peach rots in a forgotten bowl, the dust emerges-for the currents of air in the deserted kitchen. When a kettle boils unseen, the steam emerges-for the less excited particles in the water on the stove and for the framed photograph on the windowsill, whose glass it coats with a fine layer of mist.

We can trace some of the problems of certain forms of materialism to a fixation on emergence as an ontotheological fact: in this case, emergence is taken not to be emergence-for, but to operate all by itself, a kind of causal miracle. Consider the Marxist theory of the emergence of industrial capitalism. From this standpoint, it turns out that the real problem with Marxism is that Marx is an idealist, or perhaps a correlationist. How can one justify such a fanciful notion? As a matter of fact, there are plenty of ways to do this. For instance we could look at Marx’s antiquated anthropocentrism, which his beloved Darwin had blown sky high by the time he put pen to paper. But my argument here is more technical, and pertains to the issue at hand: how do things appear?

Consider chapter 15 of Capital 1. There Marx outlines his theory of machines. The basic argument is that when you have enough machines that make other machines, you get a qualitative leap into full-on industrial capitalism. Marx never specifies how many machines this takes. You know it when you see it. If it looks like industrial capitalism, and quacks like industrial capitalism, then... So what this boils down to is a theory of emergence. Capitalism proper emerges from its commercial phase when there are enough machines going ker-plunk or whatever. This is highly reminiscent of the Turing Test. [63] Intelligence is an emergent property of enough algorithms doing their thing, runs the theory. The point is, emergent for whom? If I’m sitting on the other side of the two rooms, and I receive some printouts from each room that look fairly similar, and make me think that an intelligent person is behind the door, then an intelligent person is behind the door. For a theory that tries to explain the whole of social space, this is a significant problem.

That’s the trouble with emergentism. Any system requires 1+n entities external to it for it to exist and to be measured, and so on. This is Derrida’s wonderful conclusion about structuralism. Deconstruction is often confused with structuralism—but it’s the latter that says that nothing really means anything, it’s all relational. What deconstruction argues is that for any system of meaning, there is at least one opaque entity that the system can’t assimilate, which it must simultaneously include and exclude in order to exist.

Emergence is far too slick an umbrella under which to include every causal possibility. Consider the photographs of Myoung Ho Lee. Lee simply adds a huge cloth behind a tree. Then he photographs it, creating an instant aura. It’s as if the tree appears inscribed upon a two-dimensional surface like a drawing or a painting. It’s a kind of inversion of the surrealist technique that Magritte developed. Instead of painting pictures in which pictures of trees stand in front of real trees, you take a photo of a real tree in this weird, suspended, as-if state. Adding a background is basically commenting on how for an object to exist, there must already be some other object in the vicinity. For a mark to exist, there must be ink and paper. Meaning doesn’t come from nothing. It comes from interactions between marks and inscribable surfaces. Facing us like gigantic, 1–1 scale picture postcards of themselves, the trees seem to threaten us with a clown-like artifice. The fact that you know that it’s a stage set, that you can see the wrinkles in the cloth, makes them all the more intense. Like watching someone in drag, you know she or he is performing: queer trees.

Notes

-

Harman, Guerrilla Metaphysics, 33–44.

-

Steven Lehar, “Gestalt Isomorphism,” available at http://cns-alumni.bu.edu/~slehar/webstuff/bubw1/bubw1.html, accessed July 6, 2012.

-

Graham Harman, “On Panpsychism and OOO,” available at http://doctorzamalek2.wordpress.com/2011/03/08/on-panpsychism-and-ooo/, accessed July 6, 2012.

-

Jacques Derrida, Dissemination, tr. Barbara Johnson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 54, 104, 205, 208, 222, 253.

-

Janet Murray, Inventing the Medium: Principles of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011).

-

Brian Sutton-Smith, The Ambiguity of Play (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997), 1, 22.

-

Andy Clark and David Chalmers, “The Extended Mind,” Analysis 5 (1998), 10-23.

-

Jacques Derrida, “Plato’s Pharmacy,” Dissemination, 61–171.

-

George Spencer-Brown, Laws of Form (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979).

-

Jacques Lacan, Le séminaire, Livre III: Les psychoses (Paris: Editions de Seuil, 1981), 48.

-

Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” in Margaret A. Boden, ed., The Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 40–66.