Episodes from a History of Scalelessness: William Jerome Harrison and Geological Photography

The ponderance of temporal scale is foundational for any consideration of the Anthropocene thesis. As we know, this thesis would demarcate our epoch on that imprecise though pervasively referenced scale called “geological time,” which renders sensible an earthly duration from the outer limits of the conceivable. This essay pursues such limits by considering several of the technical and poetic practices by which they were explored in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These practices have, to borrow Latour’s term, “translated” the vast temporality of the geologic, typically by way of a spatial translation into the hardness of stone or, for instance, the gradations of erosion.[1] However, as with any translation, remainders persist. The literary apparatus will provide our first brief encounter with this remainder.

In Lewis Carroll’s 1876 nonsense poem The Hunting of the Snark (An Agony in 8 Fits) we are told of a nautical crew in search of an inconceivable creature. At sea, the Bellman, provides the crew with the following directions: a blank map. It is the ocean, he claims. “And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be / A map they could all understand / What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators / Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?”/ So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply / “They are merely conventional signs!” As a map, it is a “perfect and absolute blank,” the form most appropriate for translating the ocean’s content as a vast undoing of direction, position, and scale.[2]

What the Bellman does to the ocean, Virginia Woolf applies to the body: “We are edged with mist. We make an unsubstantial territory,” she writes.[3] The first chapter of The Waves (1931) depicts a morning as the frenzied, excessive minutiae of the world begin wiggling together into a whir. A faucet begins to run; “Mrs. Constable pulls up her thick black stockings”; a door unlocks; the church bell rings, once at first, then again; a sauce pan crackles with oil. Louis, one of the characters, is left suddenly alone in the garden and his scale begins to transform. He stands looking at the grass under his feet becoming an ocean of green. He holds and then becomes the stem of a flower, but longer and deeper. He presses into the earth, passing mines of lead and silver. “I am all fibre. All tremors shake me, and the weight of the earth is pressed to my ribs. Up here my eyes are green leaves, unseeing.” But, “down there my eyes are the lidless eyes of a stone figure in a desert by the Nile. I see women passing with red pitchers to the river; I see camels swaying and men in turbans. I hear trampling’s, trembling’s, stirrings round me.” A parental yell from the house causes him to return to his recognizable form.[4]

And, again, in 1931: “Où est l’homme qui n’a pas exploré en esprit la nature abyssale?” [“Where is the man who has not explored the abyssal nature of the mind?”][5] Paul Valéry’s Cahiers incessantly return to the territory of the insubstantial to which he often arrives through this particular scene: the telescoping of the world’s detail as the body moves through space. Each thing we see is a one-sided surface hiding an infinity of details that expands and contracts according to our changing positions and their relations to each other. Valery’s paintings and drawings dwell on this very schema through an endless unravelling of the same objects. For instance, in one painting an island is pictured as a lump, in another, the same island becomes a geology of crisp, defined perimeters.[6] Scale snaps the world in and out of focus, while the insubstantial is at the edge, on the backside, and in the recesses of every scene.

Fifty years later, we return to the Bellman’s boat. In A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari adapt Carroll’s image of the sea as “the archetype of smooth space.”[7] Deleuze and Guattari devote this plateau to describing the smooth space of the sea and the various iterations it has afforded science, mathematics, art, and philosophy—each encounter either proliferating or evading its menacing qualities. In one memorable example, they offer an explication of the image of Wacław Sierpiński’s puzzling sponge: a cube precisely hollowed out by smaller cubes. Each cube is surrounded by eight cubes a third the size of the larger one; each smaller cube is similarly surrounded in turn by a constellation of eight other smaller cubes. “It is plain to see,” they suggest, “that this cube is in the end infinitely hollow. It’s total volume approaches zero, while the total lateral surface of the hollowings infinitely grows.”[8] The authors included an image of this cube. It is an impossible image in that it attempts to represent all that it is not. It is an infinite, scaleless object; it is an arresting of the object unfolding across countless scales. The image appears through, departs from, and returns to its own scalelessness like an infinite circuit.

These four episodes, spanning a century of curiosity about the inexorable problem of scale, might be productively aggregated to initiate a fictional history of scalelessness. What can we find in common among them? From even this cursory collection, two important characteristics are evidently given: the unconventionality of direction and the withering of boundaries that could determine a location. Spatial coordinates disappear into an unfathomable depth in Carroll; the body expands beyond its corporeal limits in Woolf; discrete objects lose their definition in Valéry; surface and depth become hollow in Deleuze and Guattari. In each, time and space are manifestly and corporeally infinite. That is, for each of these poetic concretions, the infinite becomes materialized and actual. Could there be other qualities of scalelessness constructed by different literatures? Can we see, at particular historical moments, more or less of a concern with this perplexing experience of scale? Is the confusion of scale intertwined with some particular historical phenomena, a reaction to something off stage? No less problematic than such queries are the definitional limitations when considering such a fictional history. How does scalelessness relate to concepts of void, the negative, or nothingness? Are these concepts each a way of describing the same experience of the irresolvable within their particular metaphysical configuration? In what follows, I attempt to open this history, engage some of these troubling questions, and trace some of the contours of scalelessness by examining a single case study comprised of a series of photographs. My approach is neither exhaustive nor definitive; instead, it is an attempt to open up a history of poetic vexation through a focused analysis of the image of scale itself.

The photographs were taken in 1886 by the geologist and photographer William Jerome Harrison, admittedly a minor figure in the history of geology, and an even less significant contributor to the history of photography. But these particular, unstudied photographs—all taken on the same day by this doubly minor character—are of interest because they appear to be the first specimens of a new type of image: photographs of everyday objects and rocks. No humans appear in these images, only manufactured objects and rocks: pocket knives, watches, hammers, basalt, granite, flint. If the manufactured objects had not appeared in the photographs, the rocks would appear without scale, the rocks could be read by observers just as easily as images of mountains or pebbles. This type of photograph would proliferate in the twentieth century as geologists began to regularly incorporate photography into their practice. But long before this trend emerged, Harrison’s photographs stand out as the first series of compositions to remove humans from the frame of the image and replace them with objects. Through this act, as the camera moves toward the technological destiny of the “close-up,” a quality of scalelessness is both subtly produced and carefully negotiated. This nimble encounter is what we can now examine in detail.

Nineteenth-century geology is an especially intriguing moment of investigation when cultivating a history of scalelessness. Its practitioners were deeply concerned with the nature of temporal and spatial scales and the possibility of experiencing the eventualities of deep time that verged on infinity. Geologists, including Harrison, were eager to account for how processes distributed over vast distances could be made legible by singular, localized marks and signs. The absolutely “scaleless” is a limit which their science must constantly negotiate; it is likewise a limit that Harrison’s work, both photographic and geological, necessarily occupies and navigates. However, these images are worthy of consideration for an additional reason. For Harrison, both photography and geology are constituted by similar processes. The technical and the geological are entangled with one another, and the human artifacts that populate his photographs are similarly imbricated in these processes as well. To be entangled is not to come away from a relation unaffected but contaminated. What Harrison thus contributes to the history of scalelessness is the use of scale itself as a medium to create improbable and unexpected entanglements among technical, geological, and human registers.

Not surprisingly, the history of scale is more easily assembled than that of the scaleless. For instance, the architectural linear scale bar, which is related to the linear scale on maps, is a technology that locks objects into a fixed spatial relation so that they can be translated from two to three-dimensional space. It appears at the intersection of the history of metric systems (and more broadly, systems of divisible numbers) and the production of precision instruments. While there are numerous examples of different types of rods and staffs used by builders, cartographers, and sailors to determine base units and translate size accurately across scales, it is not until the eighteenth century that the dramatic increase in the production of precision instruments for determining scale finally occurs. According to Pyenson and Sheets-Pyenson, this technological trajectory was driven by the new desire for accuracy that determined both the production of scientific instruments, the machines that made them, and how these instruments read the world. They write, “With Jesse Ramsden’s [...] dividing engine at the close of the eighteenth century, unusually precise scales could be turned out in great quantities. These were the scientific equivalent of mass-produced metal pots and pans at the dawn of the First Industrial Revolution.”[9] The metric system of calculation, through which mutually agreed upon base units assure a smooth transition across scales in powers of ten, was adopted throughout France in 1799 and became the standard grammar of measurement for engineering and architecture, which spoke its exactitude through manipulations in both landscape and building architecture.

William Jerome Harrison’s photographic and geological work is heavily influenced by this history of accuracy; it can be seen in his use of the instruments and conventions of precision, such as the scaled map, and through his advocacy for the visual accuracy of photography. However, his work also exceeds such a narrow preoccupation with accuracy. He was a nineteenth-century polymath who spent much of his life in Leicester and Birmingham, travelling extensively within the region to document its geology. He taught and developed the science curriculum at the Birmingham school board and, in 1877, published A Sketch of the Geology of Leicestershire and Rutland.[10] In 1888, he published the History of Photography. Both photography and geology were still relatively new inventions at the time, and Harrison was one of the earliest to integrate the two, as well as consider the implications of both practices upon one another; for him, they were two distinct but fundamentally related trajectories.

In History of Photography, Harrison characterizes the protagonists of the art form as apprentices of impressions. According to his assessment, “impressioning” is a process as ancient as the tanning of human skin under the sun, or the bleaching of wax by the sun. In each case, the sun has created an impression on a body. For Harrison, this was the earliest and most basic form of photography. Such a logic would also extend to Fabricius’ observations in the seventeenth century that mined silver and chlorine compounds would turn black when left in the sun, and necessarily include Charles’ 1780 anecdote suggesting he “obtained profiles of the heads of his students by placing them so that the required shadow of the features was cast by a strong beam of sunlight upon a sheet of paper coated with chloride of silver.”[11] However, this fine art of impressions enters its most crucial historical period, according to Harrison, with the emergence of the camera obscura. Developed by John Baptista Porta in the middle of the sixteenth century, the camera obscura was a darkened room with a single “window shutter” through which an inverted image from outside was projected by sunlight onto a white wall. Porta later added double convex glass lenses to the aperture and fixed a mirror outside to brighten and sharpen the image.[12]

When the camera obscura was combined with the chemical experiments of Nicéphore Niépce, the enclosure allowed for a greater control of sunlight’s contact with impressive media. Niépce, the under-celebrated collaborator of Daguerre, discovered the “bitumen process in photography in 1825.”[13] For Harrison, Niépce’s experiments entangle the geological enterprise with the combined architectural history of the camera obscura and the use and control of lighting conditions. Niépce studied lithographic forms of image reproduction, the geological implications of which are evident: litho is Greek for stone, and lithography is the process of imprinting an image onto a stone. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was common to use limestone as the substance best suited for receiving such impressions. Niépce considered, radically, that light could be substituted for human labour as the agent for copying images into stone. To transfer an image from a sheet of paper to a limestone surface, he first covered the limestone in a layer of bitumen, then laid the image on top and exposed it to sunlight. When exposed to light, the bitumen hardens, creating a positive imprint of the image on the surface of the stone. Niépce moved on from limestone to working with metals such as tin, and later integrated the camera obscura in the process, placing metal sheets covered in bitumen in the interior of his small camera obscura: “When exposed to the action of the light forming the picture within a camera, the bitumen became insoluble in proportion to the intensity of the light by which the various parts of the image were produced, an effect which we now know to be due to the oxidation, and consequent hardening of this resinous substance.”[14] The solubility of the bitumen on the surface created a new kind of physical landscape on the surface of the metal by fusing a stratum of bitumen to the metal. This process was named heliography—literally, “sun writing.” The only one of Niépce’s heliographs still in existence is a landscape portrait.

Harrison reads photography according to the residues of deep time contained within it; while the photograph may appear as a new technical entity, it is in reality an intensification of very old physical processes. His materialist disposition led him to tell the history of photography as a natural history rather than a history of signification or representation, as one might encounter in aesthetic or technical accounts. For Harrison, the contemporary photograph is a long accumulated history of the entanglements between techniques and material relations. The photographer is an apprentice to impressions enabled by the technical-material apparatus of the camera, plate, chemicals and light. This conception of impressions remarkably approximates another natural process, namely, that of fossilization. If fossilization is the impression of softer organisms onto harder geological forms, then photography is its modern, mediated extension. It is the impression of gradations of light and shadow onto stone, metallic, or glass surfaces—themselves the elder products of geologicial forces. This new technology is written back into the earth’s deep history. Yet such a reading is not, for Harrison, a way of naturalizing photography by wiping away its embeddeness in social relations or remove it from history by making it immemorial; it is instead a means to place the photograph deep within the history of the earth, and conversely, to treat the earth as a source of invention through the entanglements of form and matter.

Harrison’s estimation of geology is made remarkably clear in his Geology of the Counties of England and of North and South Wales (1882). It was published only a few years before his history of photography and declares many of his speculative interests. In addition to his history of photography as the art of impressions, his reading of geological time as it appears in the Geology lays the conceptual groundwork for his photographs of objects and rocks. The Geology is first and foremost an encyclopedic compendium of existing geological knowledge; it does not claim to be a presentation of new research. Its comprehensive scope is aimed at a mixed audience of both novices and experts, and it seems as though Harrison imagined a copy of the book in every British household as a way to anchor the specificity of their place within a broader narrative of geological time and transformation. In over 400 pages, the Geology accounts for every county of England and Wales in its topographical uniqueness and its deepest physical recesses. It covers the changes and re-arrangements of the ground from its distant past to its arrival in the present. The landscape becomes the physical inscription of deep time, both the result of and generator of change. It is the unthinkable immensity of time made legible and inhabitable. For Harrison, “it is certain that our earth is of exceeding antiquity,” and, in fact, “we believe in its great age because the evidence given by the rocks reveals changes, for whose accomplishment periods of time would be required, which we may attempt to estimate in figures, but whose real significance the human mind can scarcely appreciate.”[15] Even with such a caveat, Harrison remains convinced that reading, and thus appreciating, the landscape should not be restricted to specialists. In fact, while much of his research, he admits, freely builds upon and extends the work of the National Geological Survey—which was still in progress across the country at the time of the publication of Geology—it is his unique vocation to gather the results of this work and make them available to a non-specialist audience.

Harrison’s conception of the landscape presented in the Geology is the impression of a temporal and spatial scalelessness. While Harrison tends to assume a distinction between the fossil and the ground or landscape that contains it, his theory of impression simultaneously begins to undo such a distinction. When he cites Charles Lyell’s well-known definition of a fossil as “any body, or the traces of the existence of any body, whether animal or vegetable, which has been buried in the earth by natural causes,” there is an assumption that a rock or a mineral cannot, as such, be such a body.[16] However, there is evidence in both Lyell and Harrison that they understand mineralization and the formation of rocks to be made of vegetable masses, or the deep compressions of gasses, liquids, and solids under the surface of the earth. The fossil is no longer an object contained in a rock; within this logic, it becomes the entirety of the earth itself—the fossil is necessarily that which we inhabit and that which we read. The landscape crosses over to the order of the photograph, and vice versa; each an impression, each a fossil. But where light creates the impression that constitutes the form of the photograph, the form of the landscape is co-produced by the infinity of temporal and spatial scales impressed into the crevices, holes, uplifts, and protrusions over which we pass and climb, and through which we burrow.

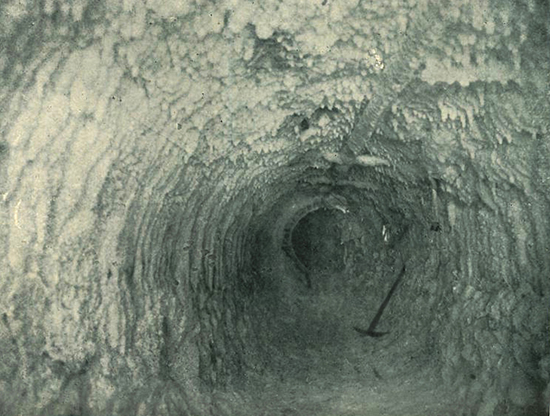

The archives of the British Geological Survey contain a series of thirteen photographs, dated 1 January 1886, which Harrison took at Sheringham Beach, Norfolk. This is the series that signals the emergence of a new form of geological photography: it includes the appearance of everyday, banal objects as scale devices. Prior to this series, human beings had been ghostly inhabitants of geological photographs, their bodies providing a scale device. However, here the close-ups of the camera capture geologic impressions at a scale too detailed for the presence of a human figure. Within geological photography this type of image does not become commonplace until some years later, largely due to the delayed uptake of the practice by field geologists. Cameras were often too cumbersome to carry on expeditions, and exposure time too lengthy to be practical. In the late nineteenth century, geological photography largely followed the conventions of landscape painting, and was mostly practiced by colonial explorers only partially familiar or interested in the emerging field of geology. By the early twentieth century, however, this type of photograph could be considered a common place in geological photography and a minor genre within photographic history; humans were replaced with a plethora of different objects in, on, or around rocks: small handbags, hammers, pocket watches, knives, picks, etc. Geologists on the hunt for resources, for instance, would photograph a small sachet, likely holding samples, or money, sitting on the shaft wall. Other photos were taken from a pit in the earth’s surface, where a small pickaxe leans on clumps of dirt. What is uncertain in these photographs is their subject: is it the object or the rocks? Rarely appearing as a mere background, the objects are given an equal compositional treatment to the geology. For instance, a small bag or a watch sit on top of a pile of rocks, a hammer shares the middle ground with the rock it leans on. Nothing in the image signifies a hierarchy of subjects. This hierarchy could only emerge through the invocation of the scale as parerga, a device subservient (and self-effacing) to guaranteeing the realism of the image, just as a scale bar on a map is only partially part implicated in the image, without sharing the status of the map itself.[17] While this tradition asserts a strong conviction, a closer investigation of Harrison’s photos reveals a strong sense that the sacks, hammers, and umbrellas in his photographs are lousy at effacement. They persist as productive remainders.

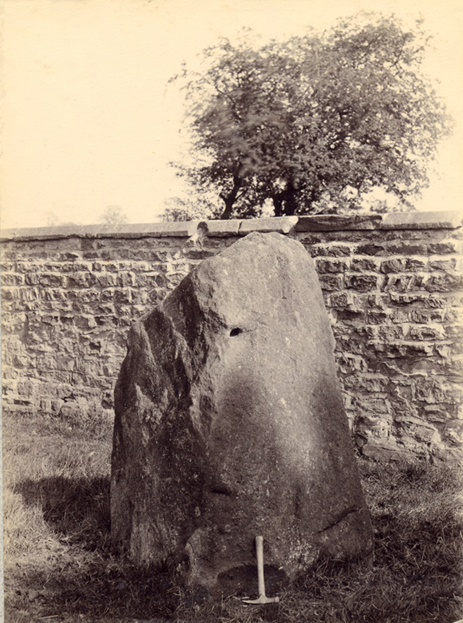

From the January 1st series, two photographs stand out. They are both of peculiar, taurus-shaped flint formations called Paramoudras. [Figs. 04 & 05] Quoting Lyell again in the Geology, Harrison describes the Paramoudra as “often hollow, and [they] seem to have been formed by the accumulation of flint around gigantic decaying sponges.”[18] How the flint could have gained its form is only imprecisely described. The photographs show the smooth surfaces of the Paramoudras bulged and cracking. In one photo, a small hammer leans against a well-formed Paramoudra set within a field of cracked bits and pieces of other Paramadouras. It is clear that it is on the threshold of a shoreline: on the left is an accumulation of rounder stones leading towards land, while to the right the ground is more advanced in its erosion and moist from the tide. The split surface of the Paramadoura reveals a darkened, thick interior. The fore-grounded Taurus stands out from the others as a more complete formation in a field of pieces that blend into the distance of the dark, wet beach stones and sand. The threshold between beach and ocean that creates the central axis of the photo is a threshold between relative rates of erosion. It suggests the gradual deformation of the rounded stones into the mud and sand that the ocean carries away, stirs up, and deposits. It is “in this way,” he says later on, that “the whole coast is receding.” The sea, he notes, “by dashing against the base of the cliffs, using as missiles the fallen stones, rapidly undermines them, when the upper part falls and is swept away by the waves: the spring slowing along the junction of pervious beds (sands) with impervious ones (clays) loosens the adhesion of the beds and the upper part slides down on to the beach.”[19] The erosion of the landscape from the coast—by rain and wind—both impresses the land into its shape while simultaneously exposing the layers of geological strata which could identify the history of its making. Naturally, the very same process that gives shape also deforms. In its deformation, the coastal landscape reveals layers of sea shells, uncovers ancient tools, and exposes settlements of communities whose organization and culture Harrison and others would speculate on. It reveals ancient water courses and the plants and animals that fed on them. Erosion both impresses and loosens, or more correctly, impresses in its loosening. Foregrounded by this deep temporality of impressioning is the paramoudra: Is it too a fossil? Lyell suggests that massive, ancient sponges gave them their form; from his perspective, and as difficult as it is to imagine, they are the negative of a mysterious, missing animal. Additionally, the photograph of the Paramoudra is an impression on a glass plate, a higher order of impression than the sponge’s impression in the Paramoudra, but fundamentally related. This is a photograph of fossils nested within fossils.

The hammer touching the right side of the Paramoudra connects it to the ground, and the ground to it, while the hammer itself is the connection between its metal head and wooden handle. There is nothing in the photo to suggest the usefulness of the hammer in the scene, no wood or nails, no construction, only shattered pieces of Paramoudra. It could be that the background has been broken as a comparative specimen to the foreground. We can also understand that the hammer, too, is a fossil, poised beside other fossils, found among the debris of the shore. Undoubtedly, it is placed in an uncertain relation with them, neither better or worse, nor more or less advanced, just touching, bridging two materialities in different states of the same process of erosion and exposure. As a fossil, the hammer is the impression of the machinic processes that formed both the wood and metal head, just as it is the impression of the person (perhaps Harrison) who placed it in the picture. Rather than a scale which would allow us to translate the accurate size of the objects in the scene, the hammer is an object poised in relation to the story of impressions and fossilization found on the beach and in the act of taking a photograph.

Another photograph from the same day shows three different exposed geological layers in a cross section. [Fig. 06] The cross section is one of the most preferred projections for stratified layers, according to the common way rock layers become exposed to the surface—either through geological forces such as uplift, or engineered exposures such as road or rail cutting. Roughly in the centre of this sectional photograph is an upright, closed umbrella leaning against a small patch of withered, scraggly grass. The different layers of rock are noticeable both through the different scales of their aggregates and their consistency. The top and bottom layers are the finer and more fragile, while the central layer contains denser, and what appear to be different, materials, slowly exposed by the erosion of the cliffs. Like the hammer, the umbrella connects different conditions within the geological strata while signaling the human. Also, like the hammer, nothing tells us that this umbrella was not also found by Harrison. Nor is the umbrella simply standing in for scale; it becomes part of the portrait. It does not disappear like a linear scale, but instead insists on becoming part of the photographic assemblage. Here we can detect the logic of material entanglements in the Anthropocene: semi-autonomous trajectories, which, at particular junctures, interfere with each other, and through their affective interference, co-produce events and their extended realities. The human artifact of the umbrella, like the hammer, is captured by the logic of the fossil, no longer set apart but instead entangled in the geological scene. The process of fossilization, as a process of impressioning, thus becomes a way of conceiving relations among the human object, the photographic apparatus, and geology. The umbrella that appears without its human figure, and like the dark, linear band in the centre of the image, becomes another geological strata.

There is in Harrison’s series a photograph which at first sight has no object or identifying feature that could indicate the proper scale of the rocks. Three layers of strata are identified, although the image appears scaleless. It is difficult to tell if one is looking at a large landscape from above or at something the size of a human hand. It is equally possible to imagine cities nestled into the crevices of the rock, or a footprint crossing it. Yet, even if Harrison had placed an object in the frame of the image, it would still not resolve the scale. Rather, it would entangle another scale, further complicating the relations among scales. It would not produce accuracy, but enfold the object within the logic of the actualization of scaleless time and scaleless space produced by Harrison’s geology and photography. As such, the scalelessness pursued in Harrison’s work is not defined by an absolute dissolution of boundaries and direction, but follows a different course. It is an accumulation of fossilized impressions expanding in space and time.

Notes

-

Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

-

Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark: An Agony in Eight Fits (London: Methuen, 2000), 45.

-

Virginia Woolf, Jacobs’s Room and The Waves (New York: Harvest Books, 1967), 9.

-

Ibid., 7–9.

-

Paul Valéry, “Pièces sur l’art,” Oeuvres, Vol. II (Paris: Gallimard, 1960), 1336. See also Paul Ryan, “Paul Valéry: Visual Perception and an Aesthetics of Landscape Space,” Australian Journal of French Studies 45, no. 1 (Jan/Apr 2008): 43–58.

-

Paul Veléry, Notebooks, ed. Brian Stimpson, (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2000). See in particular vols. X, XIX, XX, and C.

-

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 474–499.

-

Ibid., 487.

-

Lewis Pyenson and Susan Sheets-Pyenson, Servants of Nature: A History of Scientific Institutions, Enterprises, and Sensibilities (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999), 186.

-

Bill Jay, “William Jerome Harrison 1845-1909: Brief Notes on One of the Earliest Photographic Historians,” The British Journal of Photography (9 January 1987).

-

William Jerome Harrison, A History of Photography Written as a Practical Guide and Introduction to its Latest Developments (London: Trubner & Co., 1888), 7–12.

-

Ibid., 13–20.

-

Ibid., 21–27.

-

Ibid., 17.

-

William Jerome Harrison, Geology of the Counties of England and of North and South Wales (London: Kelly & Co., 1882), v.

-

Ibid., xiii.

-

Jacques Derrida, The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

-

William Jerome Harrison, Geology of the Counties of England and of North and South Wales (London: Kelly & Co., 1882), 188.

-

Ibid., 191.