The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of the Amazonia’s Deep History

Beginning in the late 1960s, a series of reports produced by various media and non-governmental agencies around the world began to expose an international public to the critical situation confronting the indigenous peoples of Amazonia, whose territories, and cultural and physical survival, were under severe threat due to the aggressive developmental programs being implemented in the region. Out of this lineage of activist reports came The Geological Imperative: Anthropology and Development in the Amazon Basin of South America, a 90-page compilation of four articles written by the North American anthropologists Shelton H. Davis and Robert O. Mathews and published in 1976. “An exercise in political anthropology,” as the authors described it, the document presented an up-to-date cartography of the depth of mining and oil-drilling activities in the former “isolated” areas of the Amazonia. Since the early 1970s, such operations had been aggressively expanding, particularly in Ecuador, Peru and Brazil, in a process that the authors associated with a condition of generalized violence and human rights violations inflicted on the indigenous communities inhabiting these lands. By offering a critical map of the contemporary context within which ethnological fieldwork was taking place in Amazonia, a situation that was representative of several other ethnographic fronts in the Third World, The Geological Imperative made a case for political engagement through anthropological practice. They contended that ethnographers should consider this specific historical conjecture and position research alongside the development program that was being deployed in the Amazon, which, at that time, was largely carried out through partnerships established between powerful multinational corporations, international financial institutions, and the militarized states that ruled much of Latin America. The proposed exercise in political anthropology did not, therefore, refer to the traditional concerns of ethnology regarding the internal symbolic order and social hierarchy that shape “primitive societies,” which the authors claimed was the dominant concern among North American anthropologists working in Amazonia. Rather, political anthropology was called on to address the role of the discipline of anthropology itself, insofar as it was inevitably immersed within, and most often complicit with, external arrangements of power responsible for, according to Davis and Mathews, the process of “ethnocide” of South American Indians.[1]

The Geological Imperative was published in the context of the contentious etho-political debates that unfolded in professional circles of North American anthropology in the 1960s and 1970s following revelations that the US Army was applying ethnographic research in the design of counter-insurgency strategies in Latin America and Southeast Asia. During WWII, with the official support and sponsorship of the American Anthropological Association, anthropologists had openly employed their expertise to help with the Allied campaign. Defined in reaction to the Nazi’s “scientific” theories of racial superiority, this war-time politicization of anthropology was accompanied by the growing militarization of ethnographic research and led to the establishment of both intellectual links and institutional networks that, in the subsequent Cold War era, would be less overtly yet more incisively applied in the service of communism-containment strategies deployed by the United States in Central and South America, Africa and Asia. Thanks to the work of the anthropologist David Price, and to the rich archive of disclosed state documents that he collected, it is now evident how the discipline of anthropology became instrumental for US intelligence agencies in the post-war period. Ethnographic expertise was especially useful to the CIA and the Pentagon when shaping counter-insurgency campaigns. Less directly associated with warfare, but equally committed to the anti-communist ideology that informed US foreign policy, anthropology also played an important role within scientific research and development programs coordinated by private foundations such as Ford, Carnegie, and Rockefeller, often in close alliance with the political economic interests of the US.[2]

In the case of Amazonia, during the Second World War, ethnographers working under the auspices of the Office of Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs were responsible for the production of maps that sought to identify potential Indian labour and locate strategic natural resources, chiefly rubber.[3] Julian Steward, a North American anthropologist whose reinvigorated vision of environmental determinism was responsible to for the “cultural ecology” sub-field of anthropology, contended that The Handbook of the South American Indian, a massive, influential ethnologic catalogue he edited in the 1940s, was also a form of collaborating in the war effort. As the director of the Institute of Social Anthropology founded in 1943 by the US State Department, Steward oversaw anthropologists conducting research throughout Latin America. He was also responsible for coordinating the compilation of large sets of data that, as David Price notes, formed an important contribution to an emergent knowledge-apparatus on “under-development, poverty and traditional culture” that would come to occupy a central place within US foreign policy.[4] Filtered through the sort of ideas promoted by economist-turned-national-security-adviser Walt Whitman Rostow and his 1960 publication The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, this literature was fundamental to the elaboration of modernization theories and development programs that the United States deployed in Latin America with the aim of containing popular support for the socialist and communist Left.[5] While the use of ethnographic intelligence as a tool for control is arguably constitutive of the science of anthropology itself and intrinsic to its colonial origins,[6] knowledge about the “culture of others” regained geo-political importance as the US either indirectly or directly attempted to expand military and political economic influence over the resource-rich, largely indigenous, frontiers of the Third World.

This was the context from which The Geo-logical Imperative emerged and in relation to which its authors contended anthropological practice should situate itself—the Cold War. With the coup in Argentina in March 1976, the United Stated added another entry to an extensive list of collaborations with military regimes that were responsible for deposing democratically elected governments throughout Latin America—Guatemala in 1954, Brazil in 1964, Bolivia in 1971, Uruguay and Chile in 1973, among others—all of which imposed murderous programs of political repression supported by successive US administrations. Overlapping interests between state and capital defined the basic framework for US interventions in Central and South America during the Cold War, as compromises with authoritarian regimes were measured both in relation to the objective of containing the Left, as well as the advantages those governments provided for the penetration of US corporate capital into regional markets.[7] For their part, the military juntas that governed Latin America tended towards a form of “modernizing capitalism,” which combined authoritarian control in planning and legislation with radical economic liberalism. The impressive GDP-growth rates achieved with this model in the early 1970s were driven by patterns of capital accumulation structurally dependant on international financial loans, corporate investment, and large-scale exploitation of natural resources for export. By the mid-1970s, when The Geological Imperative was published, countries like Brazil and Peru were trying to expand their extractive-sector economies. In parallel, the prospects of an international energy crisis triggered by the Middle East oil-embargo and the subsequent escalation in prices of raw-materials had unleashed a global rush among multinational corporations to secure supply-sources of strategic minerals and fossil fuels. The combination of these factors led to unprecedented efforts to intervene in the subsoil of Amazonia and open it to international markets.

Similar to reports produced by various US-based documentation centres such as INDIGENA, the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA), and the Brazilian Information Bulletin (BIB), The Geological Imperative was part of a wider network that served to monitor and publicize information about the participation of the US government, international corporations, and the World Bank and IMF in the policies and projects being implemented by military regimes in Latin America. At a moment when political dissidence and freedom of speech were severely curtailed across most of the continent, these publications functioned to document the human-rights record of military governments and attempted to create public pressure against the international networks that supported them. Equally significant, The Geological Imperative also engaged in the internal debate concerning the role that Amazonian ethnology was playing in the process. From mid-1960s on, in parallel to the escalation of the United States politics of interventionism in the Southern Cone and the expansion of resource-extraction activities in the Amazon Basin, Davis and Mathews noted the increasing influence of theories of socio-evolutionism on the work of North American anthropologists. They argued that the images produced and transmitted by researchers associated with this lineage were helping legitimize the processes of expropriation of indigenous territories. Exemplary socio-evolutionists included the playwright-cum-anthropologist Robert Ardrey, whose widely read 1966 book The Territorial Imperative provided Davis and Mathews with a critically appropriated title for their report. In the case of Amazonia, they listed the 1968 best-seller The Fierce People, an ethnographic account of Yanomami communities living at the border between Brazil and Venezuela by anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon. These texts promoted the notion that human societies evolve according to a naturalist path of linear progress, which Davis and Mathews criticized for reproducing the colonial logic of power that was responsible for generating Darwinist theories of social evolution in the nineteenth-century.

Given the expansion of resource-frontiers into the lands of indigenous peoples, Davis and Mathews argued that imaginaries such as those produced by Chagnon became even more problematic. Through a series articles published in magazines such as Time and National Geographic, as well as a series of films and television programs, Chagnon disseminated an image of the Yanomami as an extremely violent society, whose isolation from the outside world had preserved inherent traits of human aggressiveness, supposedly demonstrative of their proximity to the “state-of-nature” in the process of socio-biological evolution. In the hands of the modernizing governments of Brazil and Venezuela, this imaginary served to reinforce the racist perceptions driving the “civilizing” discourse that accompanied the occupation of indigenous lands. In the context of the counter-insurgent ideological apparatus nurtured by the US, such images effectively functioned as Cold War propaganda. “It is hardly surprising,” Davis and Mathews noted, “that Professor Chagnon’s early theories of Yanomamo ‘brinkmanship’ were first espoused at the highpoint of the United States military involvement in Vietnam.”[8] Like earlier ethnographic images that served to grant moral legitimacy to the slaughter of indigenous peoples and the colonization of their territories, the visions generated by Chagnon and Ardrey were accomplices in masking the social and environmental violence of Cold War’s “geological colonialism” as it expanded across the Third World. Rather than imposed by natural determinism, the imperative, Davis and Mathews concluded, was decisively ethical and political: “In contrast to those who would describe this phenomenon as a natural occurrence, i.e. as one of the inevitable results of social progress and economic growth, we see the ‘geological imperative’ as a unique historical phenomenon related to specific distribution of wealth and power which presently exists in the world.”[9]

Operation Amazonia

Beyond its historical analogy with earlier forms of colonialism, the concept of the “geological imperative” described a whole new geo-political space being shaped through the Global Cold War. Moreover, the concept also pointed to the radical reconfiguration of the natural terrain of Amazonia that took place during this period. Until the 1960s, initiatives to colonize the Amazon Basin—first by imperial powers and later by the independent nation-states that emerged in South America in the early nineteenth-century—had typically abided by the spatial arrangements dictated by the logic of territorial surface. Although there had already been some exploration of mineral and oil deposits, the subsoil had been of much less importance than both the extraction of surficial products such as timber and rubber, and the use of land for agricultural and livestock production. In the post-war decades, however, Amazonia was visualized and interpreted in its “ecological depth”: a complex environment composed of various geological and biophysical factors offering unlimited economic potential. Novel ways of identifying, charting, and accessing formerly unknown or unreachable resources created possibilities for intervention in the region at an unprecedented scale. This objective was pursued with different degrees of intensity, but largely similar spatial patterns, under the ubiquitous development ideology adopted by the states of the continental basin. For the governments of South America, the colonization of Amazonia played at least two crucial roles. First, taming the vastness of the tropical forest became symbolically important in the context of nationalist and modernizing discourses. “The incorporation of the jungle into the national economy,” wrote the Peruvian president and architect Fernando Belaúnde Terry in 1965, “is the great battle yet to be waged in the conquest of Peru.”[10] On the other hand, the region’s sheer natural wealth was considered a fundamental source for the primitive accumulation of capital that would propel these countries out of underdevelopment. Further, the understanding that Amazonia was a “continental void” to be conquered and developed was not restricted to the nationalist elites and militarized technocracy of South America, but formed part of a general perception also shared by policy makers and planners working for bi-lateral and international agencies helping to foster development in the Third World.

An extreme example of this perspective was a project promoted in the late 1960s by the Hudson Institute to build a massive dam across the Amazon River that would result in the formation of a “Mediterranean sea” at the interior of the basin. The dam was intended to function as a giant energy reservoir for South America and the US as well as a means to produce millions of migrants to populate the region.[11] Another remarkable example was a study produced in 1971 by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations suggesting that, in order to absorb the impacts of the exponential global demographic increase, Amazonia should be converted into vast agricultural fields of grain production.[12] Inside the belligerent rush for raw materials that characterized the Cold War, the Amazon Basin was conceived as a vast, primordial reserve of natural resources, which, once properly mastered with modern technologies, would serve to guarantee the development of regional economies, help to meet growing rates of world consumption, and secure steady flows of energy, strategic minerals, and fossil fuels to feed the expansion of the global military-industrial complex. Observed from a contemporary perspective, it may be difficult to imagine that such views formed the dominant development sensibility. Nevertheless, and despite the intrinsic ecologically destructive potential embodied in these views, what was consolidated in the 1960s and 1970s was a proper environmental understanding of Amazonia. Less associated with counter-cultural activism and more with neo-Malthusian manifestations of the ecological discourse that emerged at the time, Amazonia was gradually apprehended as a deep geo-physical terrain upon which a series of novel cartographic imaginaries, governmental discourses, and grand planning strategies would be projected and deployed, and which in turn would lead to dramatic changes in both its natural and social landscapes.

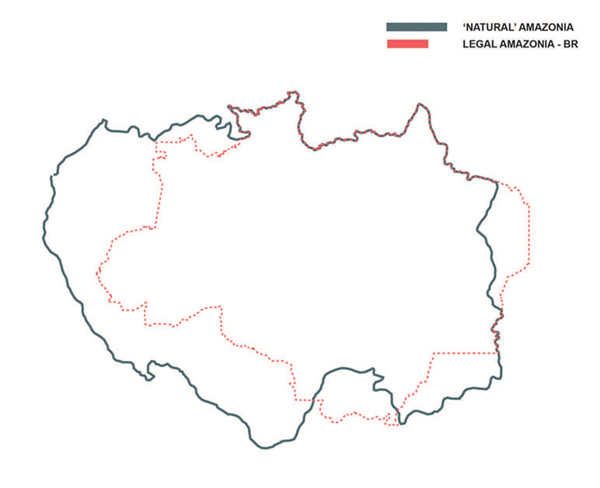

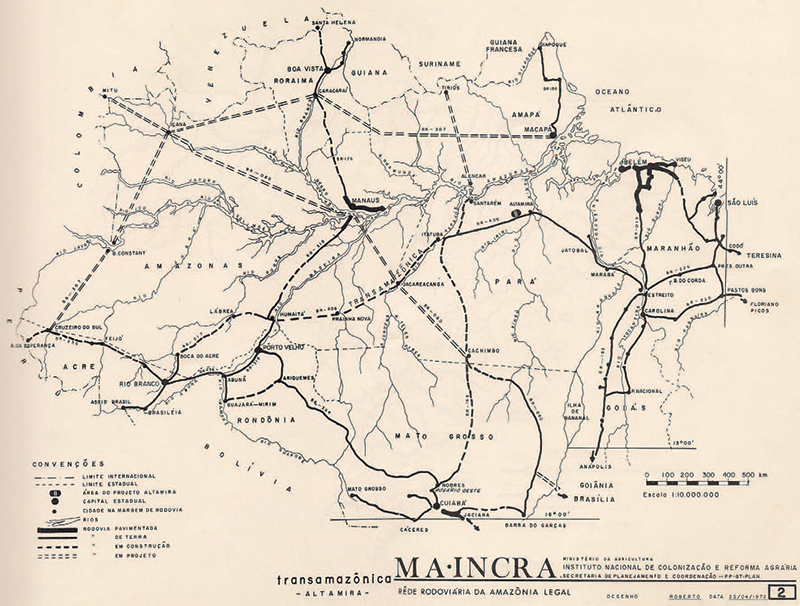

The clearest expression of this transformation was Operation Amazonia, a large-scale program of development launched by the military government of Brazil, two years after the 1964 coup, which sought to convert the entire region into a massive frontier of resource-extraction, agriculture and livestock production through the implementation of a series of projects of continental proportions. The first move in this operation was the establishment of a territorial jurisdiction named “Legal Amazonia,” which covered the whole portion of the basin within Brazilian sovereign borders—more than five million square kilometres, 59 percent of the territory of Brazil, and practically 60 percent of the natural area of Amazonia—and the placement of this vast zone under direct control of the federal government. This juridical-political regime was, in fact, not completely new. Similar forms for governing the Brazilian Amazon had already been used since the colonial period. In the mid-eighteenth century, for example, when Portuguese administrators vowed to modernize governmental practices, they instituted the “Companhia Geral de Comércio do Grão-Pará e Maranhão,” a sort of Amazonian version of the East India Company, which, like the Superintendence of Development of Amazonia (SUDAM), the agency created by the military in 1966 to deal exclusively with Legal Amazonia, functioned as a centralized administrative body directly subordinated to the executive departments of the State. Parallels between colonial and modern governmental rationales are not fortuitous, especially when they testify to the unabated perception that Amazonia was characterized by a state of chronic territorial isolation and demographic emptiness, detached from the social and political life of Brazil, a situation which, in the eyes of colonial and post-colonial governments, made the region prone to foreign invasion and economic stagnation, and which therefore called for an orchestrated and forceful strategy of occupation—i.e., a politics of modern colonization.

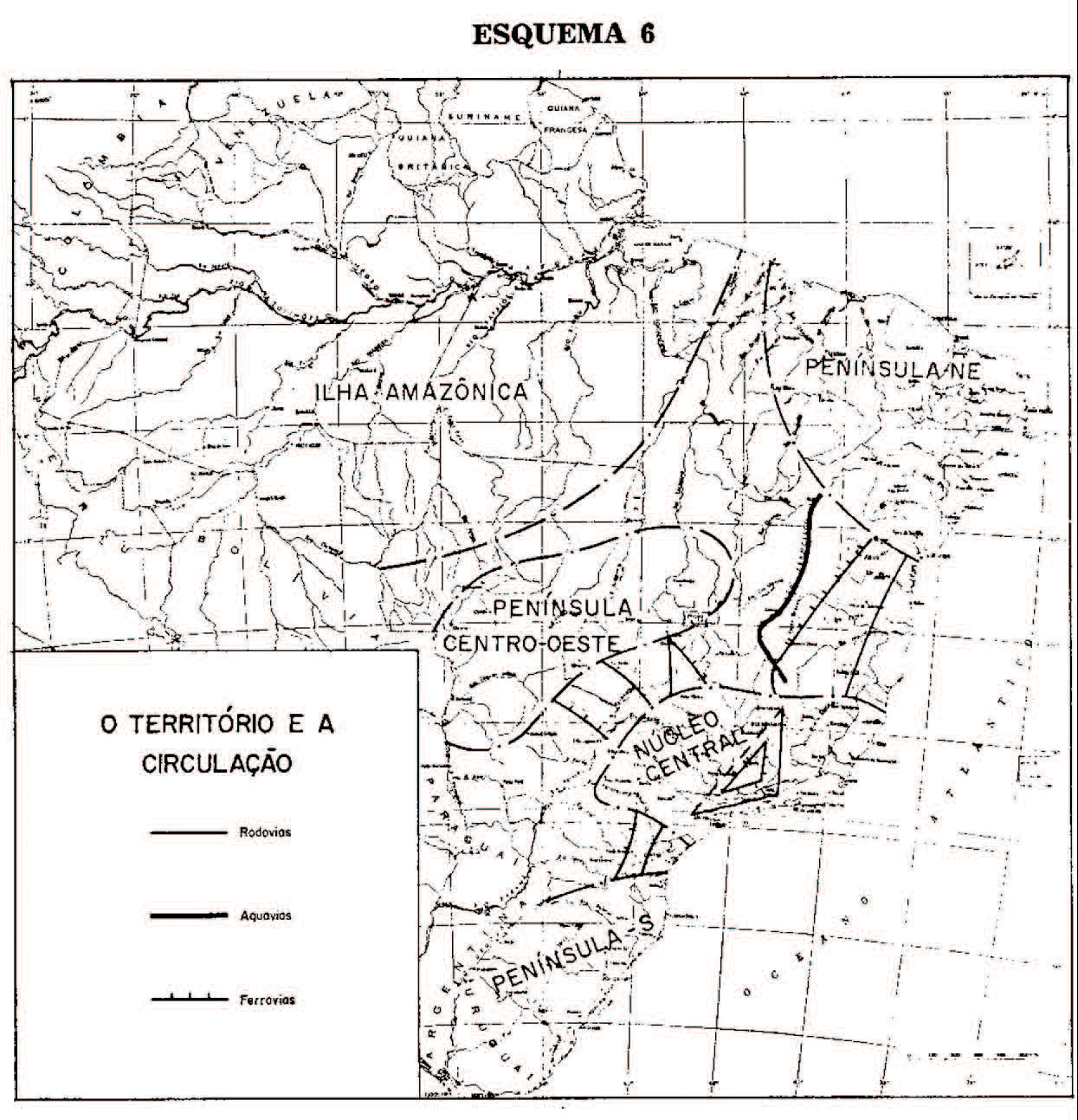

In the book Geopolítica do Brasil, a territorial interpretation of Brazilian history that exerted great influence on the armed forces during the military dictatorship, General Golbery do Couto e Silva, perhaps the most important intellectual of the regime, described Amazonia as a giant island floating at the margins of the national polity, “mostly unexplored, devitalized by the lack of people and creative energy, and which we must incorporate into the nation, integrating it into the national community and valuing its great physical expression which today still is almost completely passive.”[13] Although this perspective actualized older colonial ideologies, there are obvious radical differences that are important to demarcate. The drive to “occupy and integrate” Amazonia after the military coup was informed by the combination of the Cold War National Security Doctrine, the global hegemony that the concept of development assumed in the post-war period, and the unchallenged belief in the powers of modern planning cultivated by geographers, urbanists, economists, and all sorts of technicians and bureaucrats. Until the 1960s, the spatial organization of Amazonia remained largely defined by territorial patterns inherited from the “Atlantic Trade,” more closely connected to the river and sea than the continent. Migrant communities, towns, and cities were concentrated along major waterways and served mainly as transit points for commercial exchange. The hinterlands, where indigenous communities sought refuge, remained relatively safe beyond colonial projects and mostly unmapped. Operation Amazonia initiated a campaign that would generate a different image and completely alter the territorial logic of the Amazon watershed. By projecting a nearly symmetrical relation between an artificial political space and the natural boundaries of the basin, the operation could conceptualize and deploy planning strategies that encompassed Amazonia as a bio-geographic unit; that is, it enabled design interventions at the point where the “ecological scale” intersected with the “legal scale” of Amazonia.

Deep Cartography

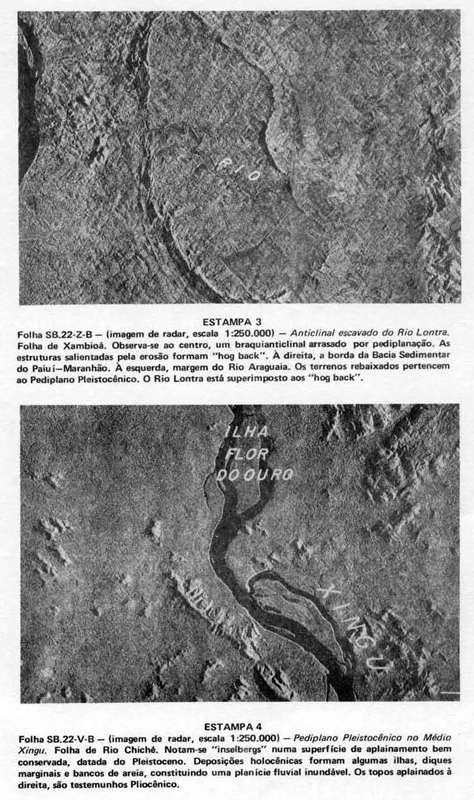

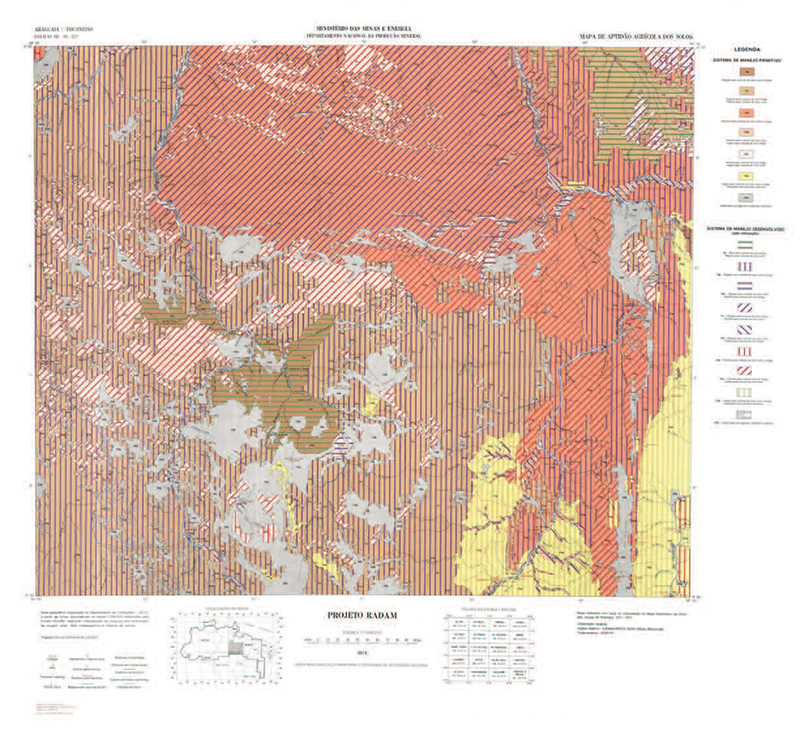

This overlap between political and natural space was forged through a peculiar combination that included the introduction of new governmental and economic frameworks (as exemplified by the creation of SUDAM and various others institutional and legal mechanisms dedicated exclusively to stimulating capital investment into the region), together with unparalleled efforts to map the geophysical and biophysical aspects of the basin. The military’s perception that Amazonia was a homogenous green void in need of occupation and modernization was also a reflection of the lack of precise cartographic information. Starting in 1970, the large-scale mapping survey conducted by NASA-trained researchers at the National Institute of Spatial Research of Brazil named Radar Amazonia—or RADAM—was as one of the most remarkable initiatives that contributed to the process of re-shaping the ways by which Amazonia was visualized and interpreted. Coordinated by the Brazilian National Department of Mineral Production, with the financial and technical support of US-AID, the project aimed at identifying mineral resources in the 44,000 km2 area along the Trans-Amazonian Highway, a major transport artery cutting east-west across the entire basin. In the following years, RADAM was gradually expanded to cover all of Legal Amazonia, and later the entire Brazilian territory. Simultaneously, the project also grew in scope to incorporate detailed geographical, geological, and soils mapping; surveys of agricultural and forest resources; hydrology and fishing charts; and the identification of actual and potential land-uses. By the mid-1970s, as one of the geologists involved in the project put it, “the imaging of the whole nation was concluded.”[14]

Before RADAM, the mapping of Amazonia had been undertaken primarily by on-the-ground surveys conducted by various military, scientific, or missionary incursions and was therefore fairly limited by the trajectories of major water channels that offered accessible routes into the harsh geography of the hinterlands. Notable examples of this cartographic archive include the early-twentieth-century charts produced by the Brazilian Army during expeditions to lay the ground for telegraphic cabling, and the detailed maps signed by North American geographer Alexander Hamilton Rice, who pioneered the use of aerial photography to map the rainforest. More recent examples are related to large state-sponsored exploratory campaigns, as in the case of the highly publicized incursions towards the Xingu River initiated in 1943 by the Fundação Brazil Central [Central Brazil Foundation], an agency created with the exclusive objective of opening up routes into southern Amazonia. In all these enterprises, the act of mapping and effective territorial control coalesced into a single practice. As such, they reproduced a long tradition in the science of cartography, whose historical evolution is often indistinguishable from the global history of colonization. Cartographic expeditions in Amazonia were responsible for creating outposts and airfields that later would serve as nodes for frontier-expansion, while at the same time they helped identify soil types, fauna, flora, and other natural resources. Moreover, those exploratory missions became important forms of gathering ethnographic information about the indigenous populations they encountered. The attendant images they produced described a fragmented mosaic of regional cartographies with little geological depth. Amazonia was, from this vantage point, viewed as a sea-like space formed by extensive macro-bio-geographical surfaces, penetrated by an intricate hydrological network of rivers and marshlands. Insofar as it was designed concomitantly to and in support of the process of “occupation and integration” launched with Operation Amazonia, RADAM helped to actualize a similar logic, but at the same time projected it on completely new terms. Because of the modern technology that was employed, a whole new picture of the natural terrain emerged, one which corresponded to the militarized forms that the process of development/colonization of the Amazon Basin assumed in the Cold War context.

By the early 1970s, following the rapid evolution of remote sensing systems designed for military reconnaissance, a series of visual technologies—multispectral aerial photography, airborne radars, and satellite scanners—became common tools for the identification and location of natural resources. RADAM’s cartographic inventory was expanded with the aid of these new Earth-sensing technologies. Most important among them was radar-imaging made possible by Side-Looking Airborne Radar [SLAR], a technology used extensively for patrolling missions at the fringes of the Iron Curtain and for battlefield surveillance and reconnaissance in Vietnam. The design of RADAM was based on a similar system pioneered in the observation-and-attack aircraft OV-10 Mohawk developed by the US Army during the Vietnam War, without the weapons. While most optical devices are severely limited both by climatic conditions and surface cover, SLAR is capable of penetrating the moist atmosphere and dense foliage of tropical forests, providing high-quality, real-time images of the terrain beneath.[15] Radar-imaging technology thus allowed for the rapid mapping of large areas of Amazonia despite the persistent cloudiness and rainfall intensity that had obstructed previous attempts to collect data. In parallel to the remote sensing efforts, the RADAM project also included scientific expeditions to collect soil-samples and ground-proofing of vegetation patterns and geological formations. With the support of the Brazilian Air Force, more than six-hundred forests clearings were opened up to receive research crews arriving with small aircraft. In total, this field-work covered more than three thousand points distributed throughout the basin at an average of more than one point per 1200 km.[16] Samples from the ground were entered into a large database of soil profiles, which, together with the cartographic analysis derived from aerial reconnaissance, were then compiled into a bulky catalogue series that provided detailed taxonomical descriptions of the biological and geophysical features of the whole territory of Legal Amazonia.

This new image of the Amazon then served as the guide for the bellicose program of economic and territorial integration put forward during the 1970s and 1980s. After Operation Amazonia was launched, successive military governments vowed to accelerate the process through the introduction of various basin-wide planning schemes. Each time, these macro-strategies assumed different titles: in 1970, The Plan for National Integration; in 1974, PoloAmazonia; each scheme perpetuated the same spatial rationale, combining the imperatives of development, the aggressiveness of extractive capitalism, and the geopolitical concerns of the National Security Doctrine. Sustained by these three powerful ideological pillars, the Brazilian military dictatorship lasted more than twenty years. On the ground, the projects unleashed a radical process of “territorial design” based on a continental network of highways overlaid with telecommunication channels and energy cables that linked strategically located “development-poles.” The poles themselves were selected according to the economic potential of the surface and the subsoil as identified by RADAM, and were conceived as modernizing enclaves that would be equipped with infrastructure, such as dams, airports, and seaports, to advance the capacity needed to enable large-scale resource extraction. The road matrix was planned as the primary means through which agricultural and cattle frontiers could expand towards the interior, while simultaneously providing routes for the massive migration of labour force. A project of this magnitude could only be implemented by a centralized and authoritarian state-apparatus, which guaranteed its enforcement through bypassing democratic debate and minimizing dissidence. Operation Amazonia, in its multiple forms and manifestations, was as much the result of the generalized state of repression that characterized this period in Brazil as well as a means deployed by the generals to achieve political containment. The discourses of modernization, security, and nationalism that supported this planning strategy played a decisive role in legitimizing the violent political order by which the military ruled, and the radical process of territorial re-organization that they imposed.

The White Peace

Published at the moment when this process was at its greatest intensity, The Geological Imperative traced a counter-cartography of the this new terrain, identifying perpetrators and collaborators, describing the forces and mechanisms that were supporting the military’s blueprint for Amazonia onto the ground, and calling attention to the intrinsic ecological and social violence of its design. As noted above, Davis and Matthews were not isolated voices. Their report was part of a larger body of literature that began to circulate after the launch of Operation Amazonia. One of the earliest and most famous manifestations was the report Genocide: From Fire and Sword to Arsenic and Bullets, Civilization Has Sent Six Million Indians to Extinction, written by journalist Norman Lewis and published by The Sunday Times in February, 1969. It gained notoriety by being one of the first reports to direct attention to what was happening in Amazonia at a moment when the human rights situation of indigenous peoples was already extremely acute. Lewis went to Brazil to report on the findings of an Inquiry Commission established in 1967 by the Brazilian Ministry of Interior, which was investigating allegations of crimes and corruption among officials of the SPI, the Serviço de Proteção aos Índios [Service for the Protection of the Indians], a state-agency responsible for implementing and governing policies directed toward indigenous communities and overseeing their welfare. Following his visit, Lewis listed a series of atrocities documented in Genocide, the twenty-volume, 7000-page report that was released by the commission in 1968, ranging from the massive usurpation of indigenous lands, to bacteriological warfare and the bombing of villages, to the abduction of children, torture, and massacres. As evidence of these crimes started to circulate globally, during the first United Nations International Conference on Human Rights, held in Teheran in 1968, the Brazilian government was accused of being complicit in the annihilation of its indigenous population, prompting more foreign observers and journalists to travel to Amazonia. Because of this attention, other, lesser-known reports also appeared around the same time as Genocide, including, for example, the article Germ Warfare Against Indians is Charged in Brazil, published by the medical attaché to the French Department of Overseas Territories at the Medical Tribune and Medical News of New York in 1969.[17] With few discrepancies, all of these reports provided a similar, haunting picture, best synthesised by Norman Lewis’s precise historical analogy: “The tragedy of the Indian in the USA in the last century was being repeated,” he suggested, “but it was being compressed into a shorter time.”[18]

Created in 1910, the SPI was a response to the escalation of bloody inter-ethnic conflicts that were leading to the slaughter of entire tribes in southern Brazil. While migrant settlers attempted to conquer new lands in order to expand coffee plantations—at that time a highly lucrative commodity and the major product of the Brazilian economy—they were met with fierce resistance from indigenous tribes. Railroad works were interrupted and agricultural colonies that had been officially established by the government were abandoned. For many people, the death of indigenous populations was not only considered an unfortunate fatality caused by the inexorability of progress, but the very means through which the hinterlands would be modernized and incorporated within the national polity. As anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro wrote in his historical account about the SPI, “the extermination of the Indians was not only practiced, but defended and claimed as a remedy which was essential to the safety of those who were building a civilization in the interior of Brazil.”[19] Whether directly or indirectly informed by racist social theories, these views were openly advocated in political and academic circles, as well as in the national press. The most infamous advocate, the zoologist-cum-ethnologist Hermann von Ilhering, founder and first director of the Museu Paulista (the History Museum of the University of São Paulo), claimed in a polemic published in the museum’s 1907 magazine that because “the savages were an obstacle to the colonization of the regions of the interior where they live, there seems no other way we can call upon if not their extermination.”[20]

In the early twentieth century, the urban elites of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, who were geographically detached from the lawless frontier zones but whose desire to emulate a Parisian cosmopolitan lifestyle was totally dependant on the financial benefits generated by the coffee economy, were facing a modern dilemma: in the name of progress and nation-building, the colonization of the hinterlands was an unquestionable imperative; however, news of the slaughter of Indians, which started to appear more frequently in the press, was also increasingly condemned as excessively violent, contradictory to the humanistic values they were keen to cultivate. For intellectuals like von Ilhering and his peers in academia and Congress, Brazilian society was to be forged on the model of the frontier ideologies that shaped the history of the United States, thus assuming the war against “hostile tribes” as a full-fledged state-policy.[21] In opposition to this expansionist view, a growing group of scientists, philanthropists, politicians, and military officers began to advocate for government policies based on the non-violent pacification and protection of indigenous communities.

The SPI was ultimately the product of lobbying efforts carried out by the latter group. Informed by the humanistic social evolutionism of Augusto Comte’s positivist philosophy, they argued that indigenous populations should be granted enough space to develop at their own pace and gradually adapt to the paradigms of modern civilization. It was therefore necessary for the State to assume legal protection over the Indians and to create an institution that would operate as a mediator between the fragile modes of life of the “primitives” and the violent forces of the expansionist frontier. The SPI was responsible for establishing peaceful contact with isolated tribes, securing lands for their survival and administering pedagogical programs that would slowly prepare those populations to be assimilated into national society. The origin of this humanitarian practice is located in the work Marshal Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon, a younger officer of indigenous descent, who, while in command of military expeditions was dispatched to build telegraphic lines towards the interior of Brazil, developed a series of innovative techniques to contact Indian tribes without resorting to armed force. The founder and first director of the SPI, Rondon’s famous motto was: “Die, if necessary; kill, never.” In the decades following its creation, the SPI established over one hundred outposts across the Brazilian territory. Initially serving as logistical centres where dispersed indigenous groups could be attracted to in order to be pacified, these encampments latter developed into agricultural and cattle farming colonies commanded by SPI officials, who were then responsible for introducing modern labour techniques to the Indians, providing medical care, and teaching them the habits of civilization and the sentiments of nationalism. The foundation of SPI marked a turning point in the relations between the Brazilian State and its indigenous population because it was the first time that indigenous cultural and territorial integrity were granted some sort of legal and institutional protection. Yet, the humanitarian governmentality that the agency instituted was hugely contradictory, to say the least. Although advocating secularism and legitimized by positivism, the SPI-model shared similarities with forms of political tutelage and territorial control employed by Jesuit missionaries on behalf of the colonial administration since the sixteenth century. The “protectionist intervention,” as Darcy Ribeiro has called it, which was promoted by the ideologues of SPI to stop the slaughter of indigenous tribes, offered a fine solution to the paradoxes imposed by the “question of the Indian” in relation to the process of territorial expansion of the Brazilian modern nation-state: simultaneously pacifist and expansionist, ideologically opposed to the extermination of indigenous populations, while at the same time serving as one of the most efficient mechanisms for opening up their lands for colonization.[22]

By the mid-1950s, when Brazil started building the modernist capital Brasília in the middle of its territory—a powerful demonstration of the program to conquer the hinterlands that accelerated exponentially in the following decades—there were alarming signals that the pacifist program launched by the SPI had been severely damaged. In a landmark report published in 1957, Darcy Ribeiro demonstrated through detailed statistics that most of the 230 tribes known in 1900 were on the verge of total disintegration, and that in the areas of expansion of cattle raising, agricultural, and mineral-extraction activities, more than 80 tribes had completely disappeared. In less than 60 years, the indigenous population of Brazil had dropped from one million to two hundred thousand, and the communities that had survived the process of contact were living in wretched conditions, facing poverty, malnutrition, disease, and depopulation.[23] Apart from a handful of experiences—the earlier heroic years of Marshal Rondon; the remarkable ethnological documentation gathered by the Studies Section founded in 1942 (in which Ribeiro worked between 1947 and 1957); and the creation of the Xingu Indigenous Park in 1961—the history of SPI was less a success than of a series of failures. Under the powerful influence of landowners and mining corporations, successive governments never really granted the financial and political support that was necessary to accomplish its ambitious protectionist mission and, with notable exceptions, the urban headquarters and frontier outposts of SPI were increasingly occupied by professional bureaucrats who showed little commitment to its original ethos. The agency found itself repeatedly threatened with extinction, accused of corruption and riddled with complaints of inefficiency. After the coup of 1964, when frontier expansion assumed the authoritarian face of the dictatorship, this situation worsened considerably.[24] As with the majority of governmental institutions, the command of the SPI was assumed by a military officer, Major Luis Vinhas Neves, who turned out to be one of the main perpetrators accused in the crimes documented by the Inquiry Commission. Amidst mounting national and international public pressure, in December 1967, a few months before the commission’s report was released, Minister of Interior Gal. Albuquerque Lima dissolved the SPI and a new institution was established, the FUNAI, the National Indian Foundation.

FUNAI was the response of the Generals to allegations that the Brazilian military regime was complicit in a genocidal campaign against indigenous populations. There were many promises of reforms that came along with the creation of the new agency. Its statute incorporated a series of progressive elements, officially endorsing the principles prescribed by the United Nations and the International Labour Organization regarding the rights of ethnic minorities.[25] In parallel, the government issued a set of decrees to demarcate five large indigenous reserves across the country, and Albuquerque Lima welcomed foreign fact-gathering expeditions to assess the situation, including a medical mission of the International Committee of the Red Cross to Amazonia in 1970 and another conducted by the London-based NGO Survival International in 1971.[26] The optimism generated by those measures was nevertheless short-lived. The establishment of the SPI Inquiry Commission and the subsequent creation of FUNAI came at a particular moment in the history of the Brazilian military dictatorship, which reflected the worldwide political expectations of the late 1960s. While protests spread through the streets of Paris and thousands marched against the Vietnam War in Washington and London, the urban squares of Rio de Janeiro were also filled with massive student demonstrations. In 1968, militant workers staged the first major strikes since the 1964 military coup, progressive members of the Catholic Church started to publicly criticize the regime, and denouncements of torture of political prisoners were openly voiced in Congress. From different corners, multiple manifestations of dissent emerged, generating a volatile situation that prompted a swift crackdown by hard-line military commanders. In December 1968, President Gal. Artur da Costa e Silva issued the infamous Institutional Act No. 5, a state-of-emergency law that gave overwhelming powers to the “Supreme Command of the Revolution” over every aspect of civilian life. From that point onwards, a much more pervasive surveillance apparatus came into effect and Brazil descended into the most repressive period of the dictatorship.[27] This radical change in the political atmosphere also had severe consequences for the indigenous populations of the country.

While the promised territorial reserves remained on paper, the philosophy of FUNAI was re-oriented towards the tenets of the National Security Doctrine. On the ground, the working agenda that the agency had to fulfil became totally subordinated to the program of “territorial design” that was deployed in Amazonia after the launch of the Plan for National Integration in 1970. Commanded by Gal. Bandeira Melo, a former intelligence officer who presided the institution between 1970 and 1974, FUNAI established a contract with SUDAM committing to the rapid pacification of the “hostile tribes” that inhabited the regions where the continental roads were being carved out, thus inaugurating a whole new phase in a long history of colonization that arguably surpassed any previous efforts.[28] It was clear that the reforms promoted by the military regime had generated little change, and if so, only for the worse. The comparison between SPI and FUNAI was even more pertinent in the context of the recently opened frontier-zones of Amazonia, with a substantial difference: in order to keep pace with the rapid advancement of development schemes, the campaign of pacification in the region became increasingly militarized. This situation was aggravated in December 1973, when dictator Gal. Garrastazu Médice sanctioned Law 6001, also known as the Indian Statute.[29] As with the document that established FUNAI, the text of this law was permeated with modern, liberal rhetoric claiming to further expand indigenous rights. However, it ruled that “interventions” into indigenous lands could be enacted in order “to realize public works” or “to exploit the wealth of the subsoil” if they were “of interest for national security and development,” and in that manner converted the violent process of territorial expropriation that was taking place in Amazonia into a legitimate, official state-policy.

Much faster than before, the interventionist policies put forward by the military regime were leading to outright extermination of entire tribes, but because Brazilian society was under widespread media censorship and political repression, it was even more difficult to report on the situation than in previous years. Yet again, attempts to mobilize international public attention started to emerge. A few days after the approval of the Indian Statute, a group of bishops and Catholic missionaries published a historical document titled Y-Juca Pirama, an expression in Tupi language meaning “he who must die.” Through a detailed compilation of facts and declarations that appeared in the Brazilian press, this report offered evidence for the allegations that FUNAI was operating with “unprofessed support” of the economic interests of multinational corporations and big landowners, further claiming that, nonetheless, the responsibility for the ongoing process of extinction of indigenous peoples in Brazil should not be attributed exclusively to the agency. Its main causes lay much deeper, the authors contended, for the practices and policies of FUNAI were in fact the result of a larger “global scheme.”[30] By the term “global scheme,” they referred to what was then known as the “Brazilian Model,” a designation used by economists to describe the articulation between state incentives, international aid, and private capital that formed the triangular base for the development program being implemented by the military regime. The violent scenario that the combination of those actors and forces unleashed in Amazonia was also denounced in another important document of this period, The Politics of Genocide against the Indians of Brazil, which began circulating in September 1974 at an academic symposium in Mexico City. For the Brazilian anthropologists who wrote this report, whose names were not revealed because they feared repression, the post-FUNAI politics of pacification launched by the military amounted to acts of genocide as defined in international law, and therefore they called on the United Nations to conduct a fully fledged criminal investigation into the practices of the Brazilian State.[31] It was in this context that The Geological Imperative was published two years later. While pointing to the participation of multinational corporations and international financial institutions in the “global scheme” that sustained the dictatorship, Davis and Matthews sought to assert their share of responsibility for what the Brazilian anthropologists claimed to be a genocidal campaign, but which they described with a slightly different concept—ethnocide.

“Genocide assassinates people in their bodies,” wrote the French anthropologist Pierre Clastres, “ethnocide kills them in their souls.”[32] Although closely related and to a large extent inseparable, these concepts were created to give name to different forms of violence, each originating in relation to a specific historical context. Coined by jurist Raphael Lemkin in 1944 to describe the systematic extermination of the European Jews by the Nazi regime, genocide was made an international crime in 1948 after the Nuremberg Trials.[33] In Lemkin’s original definition, genocide referred to an overall strategy intended to destroy in whole or in part a national, racial, religious or ethnic group; that is, the concept was invented to nominate a form of violence that was directed towards a collective qua collective. As the scholar Dirk Moses points out in a thorough analysis of the unpublished research notes left by Lemkin, his early attempts to define genocide included both physical and cultural annihilation, violence against the body and the soul. “Physical and biological genocide are always preceded by cultural genocide,” Lemkin wrote, “or by an attack on the symbols of the group or by violent interference with religious or cultural activities.”[34] The jurist considered “cultural genocide” an essential aspect of the crime he was trying to name, but due to a series of political compromises and diverging interests of different nation-states, and despite the fact that some drafts of the 1948 UN Genocide Convention did included the term, cultural genocide was erased from the codes of international law. This historical outcome, Moses argues, “advantaged states which sought to assimilate their indigenous populations and other minorities after World War II.”[35]

By the early 1970s, while new resource frontiers were expanding throughout the “isolated” territories of the Third World, militant ethnologists started to employ the concept of ethnocide to describe the dimension of cultural violence that had been left outside the legal definition of genocide. Not necessarily involving physical annihilation but equally committed to the destruction of otherness, ethnocide was the word invented to name what the Brazilian military called “integration.” It was the anthropologist Robert Jaulin who contributed most to defining the term, particularly in the book The White Peace: Introduction to Ethnocide (1970). While conducting field-work among the Bari people on the border between Colombia and Venezuela, Jaulin witnessed the campaign of assimilation to which the they were being forced to succumb, similar to the situation in Brazil, carried out by armed forces and civilizing missionaries in order to open up land for multinational oil companies. “Integration is the right to life granted to the other with the condition that they become who we are,” he concluded, “but the contradiction of this system is precisely that the other, detached from himself, dies.”[36] Whereas genocide expresses the total negation of the other with the aim of physical destruction, ethnocide is a form of violence that transforms that negativity into a positive, humanitarian intent. As Pierre Clastres wrote, “the spirit of ethnocide is the ethics of humanism,” a perverse ethos which has been historically mobilized, and is still, on behalf of establishing the “white peace.” [37]

Ecocide

“After the end of World War II, and as a result of the Nuremberg Trials, we justly condemned the wilful destruction of an entire people and its culture, calling this crime against humanity genocide. It seems to me that the wilful and permanent destruction of environment in which a people can live in a manner of their own choosing ought similarly to the considered as a crime against humanity, to be designated by the term ecocide.”[38] North-American botanist Arthur W. Galston, a pioneer inventor of defoliants and one of their harshest critics, made this statement during a panel titled “Technology and American Power: The Changing Nature of War,” at a conference organized in Washington in 1970 to debate the war crimes that were being committed by the US Army in Vietnam.[39] Words come into being to nominate existing phenomena that have not yet been given a proper description, enabling us to draw new understandings of the past and the present, and perhaps to project different futures. As with genocide and ethnocide, the concept of ecocide was invented to describe a form of violence which, although not completely new, achieved unprecedented intensity during the scorched-earth campaign that the US military forces deployed against the forests of Indochina. Certainly, the mobilization of nature as a weapon of war is as old as the history of human conflict itself. But what the conflict in Vietnam made visible was a heretofore unseen destruction of entire ecologies in a short period of time, painfully demonstrating the potential implications of the “environmental violence” intrinsic to the techno-scientific apparatus being developed in support of the Cold War, whether applied in military or civilian industries. Hence, Galston concluded his statement with the following words: “I believe that most highly developed nations have already committed auto-ecocide over large parts of their own countries. At the present time, the United States stands alone as possibly having committed ecocide against another country, Vietnam, through its massive use of chemical defoliants and herbicides. The United Nations would appear to be an appropriate body for the formulation of a proposal against ecocide.”[40] Amidst the burgeoning debate about the degradation of the global environment by civilian offshoots of the war industry, throughout the 1970s the concept of ecocide was widely debated by legal scholars, many of whom advocated that the UN should indeed follow Galston’s proposal and incorporate acts of “deliberate environmental destruction” into the list of crimes against peace.[41] Since then, discussions on whether or not to include ecocide into the frameworks of international law have continued, but no resolutions have been implemented to date.[42]

The novel methods and the unprecedented brutality of the violence unleashed since WWII forced the creation of new concepts and defied established ethical and legal codes. In the context of Amazonia, this new lexicon of destruction coalesced into a single spatial strategy. Whether or not the Brazilian military regime was complicit in acts of genocide against its indigenous populations is a highly controversial question which is only now being properly investigated after the much delayed truth commission of Brazil—the CNV, Comissão Nacional da Verdade—was finally established in early 2011. Recent disclosures of military state-archives, as well as the appearance of previously unheard testimonies, are unveiling new evidence of the human-rights violations committed by state agents during the dictatorship. It has been argued, for example, that during the construction of the BR-174 highway in northwest Amazonia, an estimated two thousand Waimiri-Atroari Indians were killed, a figure two times greater than the (contested) current official accounts of the number of murdered and disappeared persons by the military regime in Brazil.[43] What is beyond doubt is that the militarization of the politics of pacification attending Operation Amazonia was based on the logic of ethnocide, that its implementation on the ground led to the physical destruction of hundreds if not thousands of Indians and, no less important, that this process was accompanied by widespread ecological destruction.

Before Operation Amazonia, most of the land in Amazonia lacked proper legislation and was defined as terras devolutas, a form of property inherited from the colonial period which, although belonging to the state, has no defined public use, thus remaining common but available for private appropriation. As roads opened up these unlegislated areas for colonization, massive deforestation followed. The production of pasturelands turned out to be one of the most effective means used by speculators to claim and secure land titles, engendering a mechanism of “enclosure-by-destruction” that resulted in a vicious cycle of ecological and social violence that continues today. Uprooted by the expansion of soya plantations in the South and sugar-cane latifundia in the Northeast, hundreds of thousands of landless peasants migrated to the frontier zones of Amazonia to settle near the highways, only to be expelled by powerful landowners. Lacking adequate technical and financial support from the government to produce in the harsh climatic and edaphic conditions of the rainforest, large contingents opted to move to urban centres. Around the sites where large-scale extractive industries were installed and dams were constructed, old and new towns grew uncontrollably, turning Amazonia in one of the fastest growing urban frontiers in the world. Despite the grand planning strategies of the generals, cities sprawled without the necessary infrastructure and facilities to accommodate demographic increase. As Mike Davis sharply observed, in Amazonia “urbanization” and “favelization” became practically synonymous.[44]

In the mid-1980s, when Brazil was entering into a process of gradual “transition to democracy” and the ecological crisis had become an issue of broader public concern, Amazonia was turned into a powerful symbolic space of the defence of the global environment. While the decades-long development ideology was fractured by the new paradigm of “sustainability,” the remote sensing technologies introduced by RADAM were now being used to try to make sense of the scale of environmental destruction caused by the planning schemes implemented during the dictatorship. The urgent quest to monitor and preserve ecosystems became one of the most important debates inside the new forums of environmental politics, both because of the threat of biodiversity loss and because climate change was emerging as a contentious problem. Tropical forests perform a crucial function in global climate regulation, removing large amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere and locking it up in a dynamic cycle of vegetation growth and decay. Amazonia is a giant reservoir of carbon, containing roughly one-tenth of the global total.[45] When burned, it is also a powerful source of greenhouse gas emissions. In 1990, two years before the first UN Earth Summit was convened in Rio de Janeiro and months after a presidential election was held after more than twenty years of military dictatorship, the Space Research Institute of Brazil published the first detailed quantification of the scale of deforestation in Legal Amazonia. Through an analysis of LANDSAT imagery, researchers demonstrated that between 1970 and 1989 nearly 400,000 square kilometres of the original forest cover of the Brazilian Amazon had been cleared, at an average rate of 22,000 kilometres per year, equaling an area the size Portugal and Italy combined.[46] Patterns of environmental degradation in Amazonia followed the blueprint elaborated by the military and its planners, moving deeper into the jungle through the new highways and expanding in centrifugal movements from the sites where so-called development polls were installed. Often portrayed as a chaotic process resulting from lack of governmental control, the “ecocide” that spread over the Brazilian Amazon was in fact produced by design. Conceptualized and implemented at the conjunction between the natural and legal Amazonia, these spatial strategies implied forms of state intervention at the scale of basin-wide ecological dynamics, thus making the boundaries between environmental and political forces practically indistinguishable. As such, insofar as Amazonia plays an important function within the larger Earth-system, it also necessarily contained the potential of unleashing ecological consequences of global scope.

The Archaeology of Violence

Although the proposed date marking the passage from the Holocene to the Anthropocene was set to coincide with the industrial revolution in Europe, an event to which we must add the parallel movement of massive colonial enclosures and the consequential changes in land-use patterns that swept throughout the Third World as the non-European peasantry was forcibly integrated into the global market,[47] the Cold War arguably stands out as a radical and decisive turning point in the historical records of stratigraphy. At the scale of Earth’s deep time, the late twentieth century is comparatively just a tiny, insignificant fragment. But if measured in degrees of intensity, these short but extremely violent decades may be seen as a moment of exponential geochronological acceleration. Potentialized by the singular combination of the arms-race and resource-rush that characterized the Cold War, modern technology and science reached previously unknown domains in their Promethean attempt to master planetary ecological dynamics, trying to domesticate remote desert and forest lands, conquering polar ice caps and ocean floors, altering atmospheric layers and intervening into previously unchartered layers of the Earth’s crust. The capacity of anthropogenic-induced environmental modifications increased significantly as the alliance between techno-science, modern industry and militarism pushed innovations beyond the limits of the imaginable. Informed by the doctrines of development and security, and the theories of modernization and unlimited economic growth, scientists, technicians, planners, and strategists advocated for grand schemes that sought to manipulate bio-geo-physical dynamics at a planetary scale, from diverging the currents of the open seas to chemically altering vast tracts of soils, purposefully inducing weather modifications or creating an artificial Mediterranean at the middle of the Amazon Basin.[48] These geo-engineering designs were encouraged and legitimized by the geopolitics of Cold War’s bi-polar world order, and to a large extent our current perception of the nature of the globe is the product of epistemic models that were forged under this dialectic of enmity. Within this bellicose ideology, the ultimate casualty was the Earth itself. “We so-called developed nations are no longer fighting among ourselves,” philosopher Michel Serres wrote in 1990, in the aftermath of the conflict, “together we are all turning against the world. Literally a world war.”[49]

The global Cold War was fought at an environmental scale. At the same time, it was a period during which states-of-exception and political violence turned into the normalized form of governing, chiefly at the margins of the Third World, where coup-enforced military regimes were responsible for widespread killings and disappearances of innocent civilians. Most often, violence directed towards human collectives and ecological destruction were condensed as two-sides of the same rationale. Hence the paradigmatic importance of the attacks deployed by the US Army against the forests of Indochina, which were strategically conceived in terms of ecological metaphors such as “draining the water to kill the fish” or “scorched-earth.” Insofar as the crucial question posed by the Anthropocene thesis refers precisely to the impossibility of maintaining the divisions between natural and social forces that inform Western philosophy and politics, one of the crucial questions that we must ask is how the histories of power have influenced, and have been influenced by, the natural history of the Earth. The re-shaping of the nature of Amazonia that took place during the military dictatorship in Brazil was the product of entanglements between political and environmental violence, the fundamental engines of by which the “geological imperative” could be enforced on the ground. The collateral effects that ensued can be felt in the alterations of the global climatic dynamics that we experience today, transformations that are as much natural as social-political. The Anthropocene, indeed, is the product of military coups d’état.

In 1999, while flying over the south-western edges of the Amazonia, one of the regions that had been most severely affected by the colonization schemes implemented during the 1970s and 1980s, the Brazilian palaeontologist Alceu Ranzi noticed traces of various geometric earthworks of large dimensions scattered throughout the deforested areas of large cattle-ranches. The Amazonian geoglyphs, as these structures became known, turned out to be one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of recent times in Amazonia, for they are completely reconfiguring the ways by which we understand both the nature and history of the rainforest. Before Operation Amazonia, they were hidden underneath the vegetation cover. As the forest was cleared out and this region turned into a vast savannah landscape, the earthworks became increasingly visible. Because of the enormous size of the excavations, and also because they are filled with recent sedimentation, it is hard to distinguish the geoglyphs when looking from the ground. Observed from the sky, however, it is possible to identify their dimensions and territorial patterns of distribution. Using remote sensing technologies, archaeologists have located more than 210 geometric earthworks distributed over an area covering 250 km2 in western Amazonia. They are shaped in perfect circles or rectangles of 90 to 300 metres in diameter and sculpted by ditches of approximately eleven meters wide and roughly one to three meters deep, which are surrounded by earthen walls up to one meter high. Some of these giant structures are linked by walled roads, and most of them are located near headwaters, strategically placed at elevated plateaus above major river valleys from where it is possible to visually embrace the surroundings in a panoramic perspective. Archaeologists are still debating the function of these structures, some suggesting that they were ceremonial enclosures or defensive fortifications, others arguing that the ditches could have been used as resource management systems, for example, to store water or cultivate aquatic fauna for human consumption. Radiocarbon analysis of soil samples date to the year 1238, coinciding with the period of rapid urbanization of the medieval towns in Europe. Geo-archaeological data of this sort demonstrate that only as 300 years before the arrival of the Europeans colonizers, substantial populations inhabited this region of Amazonia. The archaeologists who led this research contend that many more similar structures are buried beneath the forests that remain standing, and estimate that only ten per cent of the total of possible existent geoglyphs have been identified. These impressive architectural forms are interpreted as evidences of the ancient presence of “complex societies” that for centuries modified an environment that until now we thought to be pristine. The consequent conclusion is that Amazonia’s deep history is not natural, but human.[50]

Until the 1970s, the relations between nature and society in Amazonia were framed by scientific descriptions dominated by socio-evolutionist theories, which portrayed the region as a hostile environment populated by dispersed and demographically reduced tribes, constrained by harsh environmental determinants and therefore unable to overcome a primitive stage of social-political organization and develop larger polities. During the following decades, and increasingly so in the last ten years, a series of archaeological findings such as the geoglyphs, or the identification of many sites containing terra preta—anthropogenic black-soils that are rich in carbon compounds and highly fertile—or the incredible urban clusters mapped out by archaeologist Michael J. Heckenberger at the Upper Xingu River Basin are radically transforming this image of Amazonia.[51] In a seminal article published in 1989, anthropologist William Balée estimated that large portions of upland forests were human-made, concluding that “instead of using the ‘natural’ environment to explain cultural infrastructures in the Amazon, probably the reverse should be more apt.”[52] The usual ethnological and ecological perception of Amazonia is largely derived from the eighteenth century, forged at a moment when the majority of the area's population had already been wiped out by the violence of colonial conquest. An important fact supporting these views was the lack of physical indexes showing traces of urbanization. Heckenberger’s recent archaeological excavations provide evidence that in the Upper Xingu region there existed highly populous societies, spatially organized in regional networks of fortified villages, forming a pattern that he calls “galactic urbanism.” Because of the sophisticated resource management system developed by these societies in relation to the ecological dynamics of tropical forests, he compares the Xinguano’s “regional planning” and modes of settlement and land-use with Ebenezer Howard’s model of the Garden City. “Much of the landscape was not only anthropogenic in origin but intentionally constructed and managed,” Heckenberger explains, further claiming that today we cannot assume that any part of Amazonia is pristine “without a detailed examination of the ground.”[53]

Up to now, Amazonia has been the quintessential representation of what Western civilization calls “nature.” New archaeological findings and studies are showing that, in fact, this image is the product of colonial violence. The Amazon Basin was conceived as ahistorical because of the multiple genocides and ethnocides that ravaged the region, and it was this conception of pristine and virgin nature, and the social-evolutionist imaginary that supported it, that legitimated the developmental schemes designed by the Brazilian military regime. Just as patterns of deforestation registered in Amazonia provide evidence of the social and environmental violence of the politics of integration implemented by the military during the Cold War, the earthworks unveiled by this process of ecological destruction provide evidence of a moment in which the political violence of colonialism was immediately related to radical social-environmental transformations. Their histories are separated by hundreds of years, yet they are also entangled by a historical continuum that collapses two different time-scales—the ancient and the recent temporality of Amazonia, the archaeological and the historical, coloniality and modernity—which converge into a novel natural-political territory that challenges pre-conceived notions of both nature and politics. The violence of the Cold War allowed us see the deep history of Amazonia, exposing the traces of an unknown deep past. While we look back and learn from it, we may therefore conclude that human collectives have been shaping the natural history of the Earth long before the “Anthropocenic turn,” albeit in radically different directions. Amazonia’s deep geochronology enables us to frame the Cold-War’s ecocides and genocides as an important chapter of the historical process by which geo-power—through violence, destruction, and death—came to produce a completely new natural terrain. And this is perhaps the crucial paradox that the Anthropocene has brought to light: different regimes of power will produce different natures, for nature is not natural; it is the product of cultivation, and more frequently, of conflict.

Notes

-

Shelton H. Davis and Robert O. Mathews, The Geological Imperative: Anthropology and Development in the Amazon Basin of South America (Cambridge, Mass.: Anthropology Resource Centre, 1976), 4.

-

As, for example, in the case of the study conducted in 1964 by the army-sponsored Special Operations Research Office (SORO) on the use of “witchcraft, sorcery, and magic” by rebel militias in the Congo. See David Price, Anthropological Intelligence: The Deployment and Neglect of American Anthropology in the Second World War (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), and “How the CIA and the Pentagon Harnessed Anthropological Research during the Second World War and Cold War with Little Critical Notice,” Journal of Anthropological Research 67, no. 3 (2011): 333–356. Price argues that the alignment between anthropology and warfare established in the 1940s was “normalized” and to a large extent silenced by the secrecy apparatus that surrounded military-scientific research programs during the Cold War.

-

See Gerard Colby and Charlotte Dennett, Thy Will Be Done: The Conquest of the Amazon (New York: HarperCollins, 1995).

-

On Julian Steward’s commitment to wartime ethnography, see Price, Anthropological Intelligence, 113. On the influence of his work on Amazonian ethnology, see Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Images of Nature and Society on Amazonian Ethnology,” Annual Review of Anthropology 25 (1996): 79–200.

-

On the role played by anthropologists in the application of modernization-development programs that formed part of US “low-intensity” counter-insurgency policies during the Cold War, and the relation between Walt W. Rostow’s ideas and the work of anthropologists, see David Price, “Subtle Means and Enticing Carrots: The Impact of Funding on American Cold War Anthropology,” Critique of Anthropology 23, no. 4 (2003): 373–401.

-

For example, in the case of the United States, ethnographic intelligence has been used by the US Army since the American Indian Wars.

-

Guatemala, Brazil, and Chile are notable examples of “corporate-military” coups. On the history of US interventionism in Latin America during the Cold War, see Greg Grandin, Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States and the Rise of the New Imperialism (New York: Holt, 2006), and David Slater, Geopolitics and the Post-Colonial: Rethinking North-South Relations (London: Blackwell, 2004). The origins of US imperialism over the hemisphere can be traced back to the nineteenth-century Monroe Doctrine. Between 1889 and 1934, David Slater counted more than thirty US military interventions in Latin America.

-

Davis and Mathews, The Geological Imperative, 9. What Napoleon Chagnon left outside his portrait of the Yanomami as a pre-contact society whose mode of life was determined by natural laws was in fact the very historical context within which his research was being carried out. The patterns of violence that Chagnon witnessed among the Yanomami and diffused through his films and texts were exacerbated, if not caused by, the rapid expansion of mining frontiers into their lands, as well as, by the presence of Changon himself and objects such as axes and machetes that he introduced into the villages in exchange for ethnographic information. Chagnon also allegedly collaborated in bio-genetic research sponsored by the US State Department conducted with the Yanomami. His work is now counted as one of the most infamous episodes of ethical misconduct in the history of modern anthropology. For a detailed account on Chagnon’s practice, see Patrick Tierney, Darkness in El Dorado: How Scientists and Journalists Devastated the Amazon (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002). Marshal Sahlins wrote an important review of this book: “Jungle Fever,” Washington Post Book World, 10 December 2000, http://anthroniche.com/darkness_documents/0246.htm. Chagnon was recently appointed to the US National Academy of Sciences, prompting Sahlins to resign in protest.

-

Davis and Mathews, The Geological Imperative, 3.

-

Fernando Belaúnde Terry, Peru’s Own Conquest (Lima: American Studies Press, 1965).

-

Darino Castro Rebelo, Transamazônica: integração em marcha (Brasília: Ministério dos Transportes, 1973).

-

Walter H. Pawley, In the Year 2070: Thinking Now about the Next Century Has Become Imperative, Ceres: FAO Review 4 (July–August 1971): 22–27. The article is a condensation of Pawley’s book How Can There Be Secured Food for All—In This and the Next Century? (FAO, 1971).

-

Golbery do Couto e Silva, Geopolítica do Brasil (Rio de Janeiro: Livraria J. Olympio, 1967), 40.

-

Claudio R. Sonnenburg, Overview of Brazilian Remote Sensing Activities, Report to the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) (NASAA/INPE, August 1978).

-

J. K. Petersen, Handbook of Surveillance Technologies (CRC Press, 2012).

-

Sonnenburg, Overview of Brazilian Remote Sensing Activities, 16.

-

Several articles appeared in the international press, such as “Killing of Brazilian Indians for their Lands Charged to Officials,” New York Times, 21 March 1968, and “Brazil Gets Inquiries on Alleged Indian Slayings,” Los Angeles Times, 29 March 1968. Translations of Norman Lewis’s reportage were published in the French newspaper L’Express, “Le Massacre systematic des indiens,” April 1969, and in the German weekly news magazine Der Spiegel, “Sie werden alle ausgerottet,” November 1969. For a more detailed account, see Shelton H. Davis, Victims of the Miracle (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1977).

-

Norman Lewis, Genocide: From Fire and Sword to Arsenic and Bullets, Civilization Has Set Six Million Indians to Extinction, The Sunday Times, 23 February 1969, 34–48.

-

Darcy Ribeiro, “A Intervenção protecionista”, in Os índios e a civilização (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1996), 148.

-

Herman von Ihering, “A antropologia no Estado de São Paulo,” Revista do Museu Paulista 7 (1907): 215. See also Ribeiro, “A Intervenção protecionista.”

-

Hermann von Ihering, “A Questão dos Índios no Brasil,” Revista do Museu Paulista 8 (1911): 112–40.

-

Antonio Carlos de Souza Lima, Sobre indigenismo, autoritarismo, e nacionalidade: considerações sobre a constituição do discurso e da prática da proteção fraternal no Brasil (Rio de Janeiro: PhD Thesis, Museu Nacional, 1987).

-

Darcy Ribeiro, “As Etapas da Integração”, in Os índios e a civilização (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1996): 254–293. Originally published as Culturas e Línguas Indígenas do Brasil, Educação e Ciêcias Sociais (Rio de Janeiro, 1957): 1–102. A shorter version of this article appeared as part of a report published by UNESCO in 1957, “Cultures en vie de disparition,” Bulletin International des Sciences Sociales 9, no. 3 (1957), and was later translated in H. Hopper, Indians of Brazil in the Twentieth Century, (Washington, DC: Institute for Cross-Cultural Research, 1967).

-

See Ribeiro, “As Etapas da Integração,” and specially Carlos de Souza Lima, Sobre indigenismo, autoritarismo, e nacionalidade.

-

As stated in the first article of the statute of FUNAI, these progressive measures included: “respect to tribal institutions”; the “guarantee to the permanent possession of the lands inhabited by Indians and the exclusive use of natural resources and all existing utilities therein”; and the commitment to guard against “the spontaneous acculturation of the Indian so its socioeconomic evolution proceeds safe from sudden change.” See the Legislative Decree 62.196, 31 January 1968, available at: http://www6.senado.gov.br/legislacao/ListaTextoIntegral.action?id=175883&norma=193337.

-

International Committee of the Red Cross, Report of the ICRC Medical Mission to the Brazilian Amazon Region (Geneva, 1970); Robin Hanbury-Tenison, A Report of a Visit to the Indians of Brazil (The Primitive Peoples Fund & Survival International, London, 1971). See also the report Supysáua: A Documentary Report on the Conditions of Indian Peoples of Brazil (INDIGENA and American Friends of Brazil, 1974).

-

Thomas E. Skidmore, The Politics of Military Rule in Brazil, 1964-1985 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

-