Architecture’s Lapidarium: On the Lives of Geological Specimens

I. Vital Matter: Architecture’s Material Life

Written over ten years before its publication in 1981, Aldo Rossi’s A Scientific Autobiography constitutes a peculiar point of departure for an essay in a collection devoted to architecture in the Anthropocene. On the first page of the text, Rossi writes:

Though Rossi’s anecdote constitutes an inauspicious beginning for an autobiography, his capacity to draw autobiographical, physical, and building practices compellingly into each other’s orbit succinctly establishes the claims of this essay. In the following architectural investigation of ten geological specimens, the collected examples will support the following arguments. First, a vitalist theme historically emerges at the intersection of architectural, scientific, and philosophical discourse. Second, as a result of these vitalist tendencies, the situation of architecture—that which historically was conceptualized as “site,” and its material constitution—ceased to be represented as a static or benign entity. Third, the influence of vitalism also introduced the term “life” as the chronological measure of agency, both human and inhuman, organic and inorganic, facilitating the comparison of human and geological agencies that is characteristic of the Anthropocene. Fourth, this metric—“life”—emerges from the overlap between the introversion of biological discourse (searching for the smallest unit manifesting life), and the inner investigations of autobiographical work (examining how a given character has come into being, how an individual life acquires meaning). In biology and autobiography, “life” is both the unit of measure and the evidence of immanence. And fifth, the ten geological specimens in architecture’s lapidarium construct a foundation for an understanding of life as the measure, and immanence as the operative condition, of architecture in the Anthropocene.

Returning now to the first specimen, Rossi cites two primary influences for his autobiography: Planck’s Scientific Autobiography (published in German as Wissenschaftliche Selbstbiographie, in 1948, and in English in 1949), in which the physicist narrates the events leading up to his formulation of the principle of the conservation of energy; and Stendhal’s The Life of Henry Brulard (written between 1835 and 1836, and published posthumously in 1890), a thinly veiled fictitious account of the author’s unhappy childhood.[2] Stendhal’s work interested Rossi for its strange mixture of autobiography and architectural plans—Stendhal elected to illustrate this account of his life, not with perspectival vignettes, but rather with planimetric fragments.[3] Of Stendhal, Rossi writes:

In this sense, the autobiographical account and the architectural plan are parallel operations for Rossi in that both are activated by a vital energy, manifesting itself either as an event or a formal configuration. Here, it may be worth noting that Stendhal is a nom de plume for Marie-Henri Beyle, selected in hommage to Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who was born in Stendal, Germany. Winckelmann is known for bringing natural historical taxonomy to art historical discourse, and in this sense his categorization of cultural artifacts into periods and styles could be similarly characterized as a moment of fixity within a fluid historical continuity.[5]

What is the common ground between cultural artifacts and the categories that house them, between disparate pseudonyms and the author who creates them, between the architect and the spatial configurations he imagines, and between the autobiographer and the narrative he recounts? In each of these instances, the common ground resides in the conceptualization of “life” as the critical unit of chronological measure. In his essay “Of Crystals, Cells, and Strata: Natural History and Debates on the Form of a New Architecture in the Nineteenth Century,” architectural historian Barry Bergdoll observes that the three defining texts of nineteenth-century architectural theory—Ruskin’s Stones of Venice (1851–1853), Viollet-le-Duc’s Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française (1854–1868), and Gottfried Semper’s Der Stil (vol. 1, 1861, vol. 2, 1863)—are all “shot through with geological references that seek to bring the century’s fascination with the study of the history of civilization into line with the new insights into the expanded timeline of the history of the earth itself.”[6] Bergdoll’s characterization of this desire for the synchronization of human time and geologic time is supported by Martin J. S. Rudwick’s reminder that geology and biology are terms both coined at the start of the nineteenth century, and that their emergence occasioned a reorientation of the map of knowledge.[7] Rudwick writes: “The relations between the various natural sciences, and between them and the social sciences and humanities […] are not intrinsic to the natural and human worlds: all our maps of knowledge are themselves human constructions, embedded in the contingencies and specificities of history.”[8] Rudwick’s framing of historical contingency as that which unites the sciences and the humanities proffers a unit of measure for the attempted synchronizations of nineteenth-century architectural theory—a life.

In his 1995 essay “Immanence: A Life…,” Gilles Deleuze draws the distinction between a life, and an immanent life: “A life is everywhere, in all the moments that a given living subject goes through and that are measured by given lived objects: an immanent life carrying with it the events or singularities that are merely actualized in subjects and objects.”[9] Somewhere in Deleuze’s formulation of immanent life lurks Rossi’s desire to “stop the event just before it occurs”—both characterizations allude to potential, prior to its realization. In Jane Bennett’s interpretation of Deleuze, her attention focuses on the philosopher’s use of the indefinite article “a,” and his reference to “a life,” because, “[a] life inhabits that uncanny nontime existing between the various moments of biological and morphological time.”[10] Like Bergdoll, Bennett points to the reckoning of human and geological time, but unlike Bergdoll, she establishes “a life” as the potential interface between the two. Bennett continues: “A life thus names a restless activeness, a destructive-creative force-presence that does not coincide fully with any specific body. A life tears the fabric of the actual without ever coming fully ‘out’ in a person, place, or a thing. A life points to what A Thousand Plateaus describes as ‘matter-movement’ or ‘matter-energy,’ a ‘matter in variation that enters assemblages and leaves them.’”[11] Alternatively, Giorgio Agamben’s interpretation of Deleuzean immanence concentrates not on the indefinite article preceding life, but rather on the semantic connotations of Deleuze’s punctuation, specifically the colon and the ellipsis in his title. Agamben argues: “If we take up Adorno’s metaphor of the colon as a green light in the traffic of language, […] we can say that between immanence and a life there is a kind of crossing with neither distance nor identification, something like a passage without spatial movement.”[12] For Agamben then, the colon intimates a departure from immanence as a state of being towards something like “immanation” (Deleuze’s term): activated possibility that is not yet actualized, catalyzed potentiality that is not yet realized—in other words, virtualization. With respect to the ellipsis dots following “a life” in Deleuze’s title, Agamben reasons: “Here the incompletion that is traditionally thought to characterize ellipsis dots does not refer to a final, yet lacking, meaning […] [R]ather, it indicates an indefinition of a specific kind, which brings the indefinite meaning of the article ‘a’ to its limit.”[13] According to Agamben, taking the colon and ellipsis together, “a life…” is “pure potentiality that preserves without acting.”[14] Thus, to conclude the interpretation of this first geological specimen, if the vital force that inhabits Max Planck’s example of the schoolmaster Mueller’s stone is conserved energy, and the vital force that Rossi identifies in Stendhal’s plan fragments resides in its capacity to stop an event before it has occurred, then Rossi’s geological specimen frames this vitalist immanent life as pure potentiality.

II. Geological Life: Some Mythological Narratives

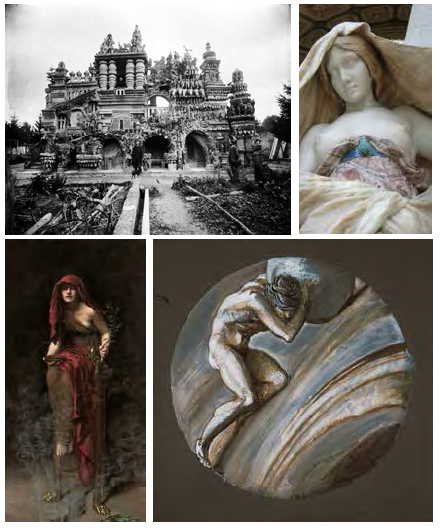

The second specimen explores the notion of geological life through four mythological (or at least mythical) narratives that consider the intertwining of the earth’s history with human history. The mythological account is a useful vehicle for exploring the idea of geological life, largely because it is pre-scientific, so its tendency is to narrate through engagement, rather than to explain from a distance. The subject of Louis-Ernst Barrias’ sculpture is the Egyptian goddess Isis, identifiable by the green scarab perched upon the cloth beneath her breasts. Isis was a seminal figure for the Romantics, and Friedrich Schiller wrote about her in the poem “The Veiled Image at Saïs,” published in 1795 and translated into English by Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton in 1866. In the poem a young man travels to Egypt and is told that behind the veil of Isis lays the truth, but he is cautioned not to lift it. Why this admonition against lifting the veil? Jean-Paul Sartre writes: “What is seen is possessed; to see is to deflower. If we examine the comparisons normally used to express the relation between the knower and the known, we see that many of them are represented as being a kind of violation by sight.”[15] For Sartre, visual examination is critical to the scientific paradigm, and the Romantic caution against lifting the veil is directly linked to the desire to preserve the participatory, connective, and immersive dimensions of knowing affiliated with the mythological paradigm. Similarly, Karsten Harries writes:

The Romantic obsession with the veil of Isis, then, is a cautionary tale about the human desire for omnipotence, a desire that in Barrias’ sculpture is combined with the scientific gaze. And yet, this representation of Isis seems to willingly and without coercion lift her veil, as if nature is eager to reveal her secrets to the inquiring scientist. What the narrative of Isis demonstrates is the precariousness of mythopoeic propinquity in the modern advent of the distanced scientific gaze.

John Collier’s depiction of the Priestess at Delphi represents the oracle perched on a tall stool, hovering above a chasm in the earth that appears to be emitting steam or gas. In his discussion of the Delphic oracle, Steven Connor observes that the association of females with the earth is commonplace in many cultures. He writes: “The female earth is thought of as valuable enclosures or interiorities. In particular, vases which hold grain, oil, or wine, and ovens that transform grain into bread. This emphasis upon valuable interiority made openings in the earth extremely significant. Such openings, in the form of chasms and caves, were at once the confirmation and transgression of the earth’s power to hold and store items of value.”[17] The oracle’s power is derived from her proximity to the earth, both physically and metaphorically, and from this proximity comes her ability to speak for the earth, to interpret its emissions. Page duBois alludes to the tradition of the oracle being a post-menopausal woman, a figure who “must remain pure potential, never having their interior filled up by sex or pregnancy, so that other processes of thesaurization can occur.”[18] Poised upon a golden-footed stool that straddles a fissure in the earth’s surface and ensconced in the emitted vapours, Collier’s oracle is a metaphysical trope, translating and rendering immanent the unleashed generative potential of the earth.

Another mythological narrative that takes up this theme is Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus (published in French in 1942, and English in 1955). Captured in Edward Burne-Jones’ painting (c.1870), Sisyphus is condemned, by the gods, to the futile physical labour of continually pushing a boulder up a hill. Upon reaching the apex, his onerous task accomplished, he is then fated to witness the boulder’s retreat, secure in the knowledge that his labour was entirely in vain. Camus writes:

In his analysis, Camus isolates this hiatus from labour, this moment of consciousness, as an instance of affinity between the anthropological and the geological, and moment of identity, or even empathy, between man and stone. The two are at once the same and yet different—Sisyphus is already stone, yet he is stronger than rock—and a vital exchange has occurred between the life of the boulder and the life of the man whose fate is inseparable from this geological burden.

Finally, a mythical (if not mythological) exemplar of geological life resides in the urban legend of the French postman, Ferdinand Cheval. In April 1879, Cheval tripped on a stone along his typical route, and was so taken by it, that for the next 33 years he collected specimens during his mail rounds, and with them constructed the Palais Idéal. Once again, the respective fates of man and rocks are inextricably intertwined. Embraced by the surrealists, and particularly by André Breton, Cheval’s masterpiece came to epitomize the ambitions of automatism—a seamless connection between reality and dream. If, in Camus’ hands, the myth of Sisyphus encourages the reader to contemplate some sort of vitalist exchange between man and rock, Cheval’s Palais Idéal conjures another manifestation of these generative forces as they ignite the postman’s material imagination in the implementation of a geological dream world.

III. Generative, Taxonomical, and Mathematical Immanence

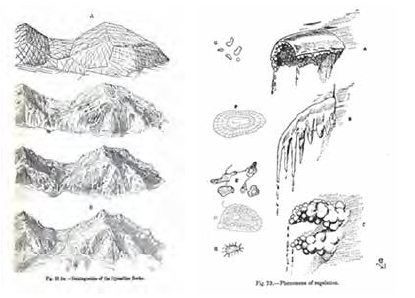

In 1876, French architect, theorist and restoration specialist Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc wrote a lengthy tome on Mont Blanc, on its geological and geodesical formations and transformations, as well as on the current and past state of its glaciers.[20] The first image of Viollet-le-Duc’s text is neither scenic nor pictorial; rather, it is a diagram depicting the process of geological upheaval in its before and after states. This is significant in that Viollet-le-Duc elects first to demonstrate nature’s behaviour before representing nature’s appearance to his readers. In his description of immanence, Deleuze writes: “Absolute immanence is in itself: it is not in something, to something; it does not depend on an object or belong to a subject.”[21] In his depiction of this geological phenomenon, Viollet-le-Duc is representing a process, the process of upheaval, and in this sense his diagram of forces has no subject—it is all verb. Viollet-le-Duc’s other texts equally reveal this propensity for the representation of immanent natures. His 1875 History of Human Habitation examines the perennial practices of domestication, while Learning to Draw (1879) and The History of a House (1873) are thinly disguised Bildungsromans in which the process of cultivation is emphasized over the cultivation of an individual.[22]

In “Disintegration of the Crystalline Rocks,” Viollet-le-Duc depicts the morphological “life” of Mont Blanc. Interestingly, however, none of the four images depicted in this mathematical regression is an actual representation of Mont Blanc. Viollet-le-Duc renders this drawing as if the process of crystalline disintegration had a life of its own, independent of Mont Blanc or the specificity of any other geological formation. Similarly, his illustration of the phenomenon of regelation is revealing. Here, Viollet-le-Duc attempts to taxonomically depict matter that is undergoing a change of state. Anticipating Henri Bergson’s vitalist assertion that “form is only a snapshot view of a transition,” Viollet-le-Duc produces stop-motion imagery at both micro and macro scales, making the process of glacial formation immediately intelligible.[23] In thus depicting geological formation (the process of upheaval), geological erosion (crystalline disintegration), and glacial changes of state (regelation and compression), Viollet-le-Duc’s representations of Mont Blanc epitomize Deleuzean “immanence”: a process that is always yet “in the making.”[24]

IV. Technical and Tectonic Immanence

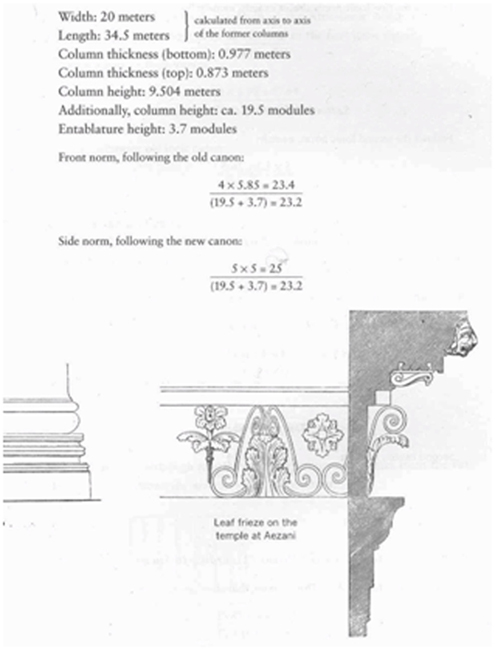

By contrast, in Gottfried Semper’s hands, the subject of geology is always already categorized through the material specificity of stones of a particular sort, and through the tectonic lens of stereotomy. In his seminal text, Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts or, Practical Aesthetics (1860–63), stone is conceptualized as a building material inseparable from the techniques through which it is prepared for construction. When Antoine Picon addresses architectural construction, he describes it as being “on the verge of speaking,” but in Semper’s case, the techniques of stereotomy are both a priori and prescriptive, and in this sense, the stone already knows what it is going to say. Paradoxically, Semper discusses the techniques of stereotomy before he ever considers the materiality of stone, exacerbating this omission by positing the question: “But did stereotomy, in fact, have no original domain to it?”[25] What follows this question is a historical discussion of the hearth, indicating that Semper is operating under the assumption that the ontology of stereotomic technique can be traced back to the central element of a primitive building form.

Following a similar logic, Semper then discusses the foundation wall:

With respect to the geological specimens under consideration, Semper’s prioritization of stereotomy and its attendant mathematization of stone epitomizes technical and tectonic immanence. The characterization of a foundation wall as a “lifeless,” “self-contained whole,” that “denies any external existence,” articulates a moment in which technique eclipses material possibility, in which the “how” of stereotomy’s mathematical capacity to fashion stone supplants the “what” of traditional material iconography. In Semper’s hermetic world of construction, in his “crystalline universe,” any vitalist aspirations for the generative capacity of stone are channelled into the mathematical proprieties of stereotomy; the stoniness of stone capitulates to the human techniques through which it is fashioned towards technical and tectonic ends. The life of Semper’s stone is mathematically predetermined as it succumbs to the exigencies of construction practices. For Semper, geological knowledge is thus confined to the epistemological horizon of stone as building material, and this horizon is squarely located between column base and frieze in the mathematical and tectonic expression of stereotomy.

V. Aesthetic Immanence

The first chapter of John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice (1851–53) is entitled “Quarry,” a rubric that definitively established the inextricability of human and geological history, given that the chapter is primarily concerned with the political and religious history of Venice. The first image of Ruskin’s book, a “Wall Veil Decoration,” illustrates the story of an ambassador who arrived in Venice in the fifteenth century and immediately recognized a change in its architecture. Here, Ruskin argues that Greek architecture was “clumsily copied” by the Romans. Following on the heels of this anecdote, Ruskin admits his desire to establish a law for architecture, like the one that exists in painting, which would allow for a distinction to be drawn between good architecture and bad. He writes: “I felt also assured that this law must be universal if it were conclusive; that it must enable us to reject all foolish and base work, and to accept all noble and wise work, without reference to style or national feeling. […] I set myself, therefore, to establish such a law.”[27] Ruskin rationalizes his search for such a law by revealing his aspiration to establish the very foundations of architectural criticism.

Given that Ruskin would like these foundations to be discerning and capable of eschewing the clumsy copy with which his text begins, his language then takes up the tropes of geological formation: “And if I should succeed, as I hope, in making the Stones of Venice touchstones, and detecting, by the mouldering of her marble, poison more subtle than ever was betrayed by the rending of her crystal”—his description concludes with the promise to access a more vital truth.[28] Here, Ruskin’s language of geological decay (mouldering), geological examination (touchstones are assaying tools used to identify precious metals), and geological formation (the process of crystallization) lays the foundations for an aesthetic law that will not falter in the face of substandard stylistic copies. Though the operations of geological formation and human cultural production may parallel one another, aesthetic judgment should emulate nature’s generative processes in order to fulfill its universal aspirations. Ultimately, the moralizing tone of Ruskin’s nascent architectural criticism emanates from this desire for aesthetic law to mimetically replicate natural law, ensuring historical continuity and safeguarding against stylistic anomaly.

VI. Origins: The Inception of Immanence

Architecture: Its Natural Model (1838), specimen six, is Joseph Michael Gandy’s pictorial narrative on the entanglements of human and geologic time. In the foreground, a group of primates (an obvious allusion to human evolution) crafts a primitive hut through the bending and lashing of tree branches. In front of the hut, a primate with a simian head and human body perches, “unaware of the basaltic fragment on which he is seated, the faceted and monumental ruins of this Classicizing geology spilling all around him.”[29] Here, the primate evolving into a human before our eyes occupies a “Classicizing geology”—a stone poised somewhere between its geological formation and its cultural articulation as column. Behind this hut looms Fingal’s Cave—a geological tourist attraction in Scotland—conveying the message, “the future history of architecture was already written in the landscape, merely waiting for human civilization to catch up.”[30] The formal affinities between the manmade shelter and the geologically wrought cave attest to this.

Gandy’s watercolour, the only surviving image of his Comparative Architecture series at the Royal Academy in London, was exhaustively described in the exhibition catalogue. It is something of a geological capriccio, a collection of the world’s most remarkable geological formations assembled as if they occupied a single site. Etymologically linked to the word “capricious,” the capriccio emerged as a representational genre in the seventeenth century, at a moment when the cosmological paradigm was gradually being eclipsed by modern historical and scientific paradigms, with their attendant notion of individual human agency. Here, the whimsy of the geographical imprecision of Gandy’s collection—the image includes the natural arch from Mercury Bay in New Zealand and the rock formations of Cappadocia in Anatolia—meets the accuracy of the modern scientific gaze and the temporal agency of the new historical worldview. Gandy wrote: “Men who traverse this earth and examine the animal, mineral, and vegetable kingdoms find a succession of models for his artificial fabricks. […] The philosophy of architecture is a sketchbook from nature.”[31] Though the capriccio genre was commonplace in Gandy’s time, the paradox raised by the idea of a geological capriccio is compelling because it posits the operations of geological formation between site-specificity and human agency.

Perhaps Gandy’s primary contribution to the genre resides in his acknowledgment that the assembled collection need not be capricious; in fact, as an aggregate it has the capacity to describe a life, as was the case in his homage to John Soane. In 1818, Gandy produced a painting entitled A Selection of Buildings, Public and Private, Erected from the Designs of John Soane, commemorating Soane’s contributions as an architect and antiquarian. If in this case Gandy is describing an immanent history, the life he alludes to in Architecture: Its Natural Model is a geological life. In reference to such evocations of “life,” Deleuze writes: “The life of such individuality fades away in favour of the singular life immanent to a man who no longer has a name, though he can be mistaken for no other.”[32] There is little wonder that Gandy is possessed of a geopoetic imagination that allows him to speculate upon such a geological life. “Matter-movement” stilled in the process of construction or halted in the attrition of ruination had long been the ostensible subject of his representations, as evidenced by his seminal image A Vision of Sir John Soane’s Design for the Bank of England as a Ruin (1830). With painstaking attention to detail, Gandy represented immanent life—the life of a building, the life of an architect, the life of a geological specimen—seamlessly eliding natural creation and human production, and ultimately paving the way for an architecture of the Anthropocene.

VII. Resource

Contained within the ideological ruminations of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ The Communist Manifesto (1848), is this tribute to the productive knowledge of the bourgeoisie:

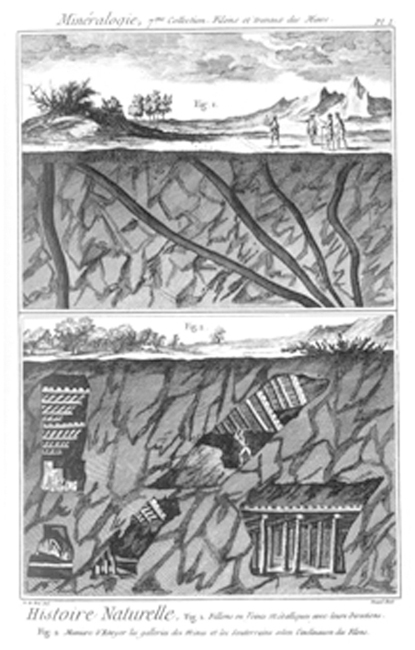

What Marx and Engels are witnessing, in this and other passages, is the commodification of the natural world into resources (to be used, and used up), as well as the reification of its vital forces into labour and energy. What transpired during this century of bourgeoisie rule that occasioned such a massive reconceptualization of the natural world? Between 1751 and 1777, Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert published the 32 volumes of the Encyclopédie, a comprehensive and exhaustive documentation of modern knowledge.

Part of the project of the encylopedists was to classify geological and mineralogical resources, and to document the various technologies deployed for extracting them from the earth. As a result of eighteenth-century archeological and antiquarian activities, the earth acquired a new perceptual depth, facilitating the conceptualization of the natural as immanent history, and of the earth’s materials as resources that could be extracted just like archeological artifacts. Natural dispositions were reconfigured into productive knowledge, as in geological specimen seven, an illustration demonstrating the virtue of constructing galleries and tunnels according to the inclination of the veins being mined. Typically, in these encyclopedia images, a sectional view of an underworld of resource extraction supports the unfolding perspective of a productive landscape, in which the resources are utilized towards highly differentiated ends of cultural fabrication. In this sense, these types of images constitute a thickening of the epistemological horizon, as they cultivate new territories for the imposition of productive knowledge. Eventually, the technologies of extraction begin to eclipse the commodification of the earth’s resources in such a way that the instrumentalization of the process and the productive knowledge it proffers become the ostensible subject of these images. The geological life depicted by the encyclopedists is a life of resource extraction, energy production, and commodity consumption, epitomizing Nietzsche’s “monster of energy” in the escalating supply and demand of the emerging capitalist economy.[34]

VIII. Foundations

In the context of Venice, foundations consist of wooden piles made from the trunks of alder trees, submerged in the waters of the Adriatic, sitting upon a soft layer of sand or mud, then upon a harder layer of compressed clay. Giovanni Battista Piranesi, born in Mogliano Veneto on Venetian terra firma, laboured under both a Venetian preoccupation with foundations and an antiquarian curiosity about the ground upon which he stood. His preoccupation with foundations, both literal and figurative, is also attributable to the aftermath of the Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns, a late seventeenth-century literary and artistic debate over the origins and foundations of modern European culture. It is as critical to historically situate Piranesi’s work in its aftermath as it is to situate it geographically. Piranesi’s desire to excavate a legitimate and appropriate historical past to substantiate his contemporary culture; his ambition to make the unseen geological substrate, laying beneath the horizon, into a visible and intelligible traditional footing; and his attempt to exaggerate archeological legacies; all point to an explicit aspiration to construct cultural foundations in a moment of epistemological uncertainty. In 1756, he produced a volume on the architecture of Roman antiquity, Antichitá Romane, which warrants some comparison with Michel Serres’ text Rome: The Book of Foundations. Serres writes: “Ad urbe condita. Foundation is a condition. The condition is union—that which is situated or put together, stored away, held in reserve, locked up in a safe place, and thus hidden from the gaze, beyond understanding.”[35] If, for Serres, foundations are hidden from the gaze beyond understanding, the horizon of epistemological intelligibility has expanded into subterranean territories for Piranesi.

In her seminal text Body Criticism: Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine, Barbara Maria Stafford describes the corrosive process of Piranesi’s etchings as a parallel operation to an archeological imagination that sees under and through, visually dismantling the surface of things. She writes: “Piranesi’s radical experimentation with etching, a corrosive chemical process for biting a copperplate, permitted him to perform perceptual rescue work. He artistically unearthed the mutilated corpse of Italian antiquity.”[36] Aspects of Piranesi’s “perceptual rescue work” can be seen in his “Foundations of the Theater of Marcellus,” (geological specimen number eight) in which the scalar exaggeration of the monument manifests certain cultural foundational anxieties. Lurking beneath the sterilizing tendencies of the Enlightenment tabula rasa and the new epistemologies it would support, Piranesi literally unearths a history both experientially distant and immanently present. The intelligibility of human history parallels the intelligibility of natural history—the foundations for both are accessible and understandable. As Stafford eloquently states, “There was an intimate connection, then, between the etching process and the exploration of hidden physical or material topographies. Important, too, was the entire panoply of probing instruments, chemicals, heat and smoke, revealing and concealing grounds.”[37]

In a quite different representation of foundations from the same text, Piranesi stumbled upon a pile of rocks on the site of the ancient Mausoleum of Cecilia Matella, and became curious about the peculiar notches carefully cut into the discarded stones. These markings allowed Piranesi to reconstruct the monument and speculatively represent the complex block-and-tackle system he imagined was deployed in its construction. This depiction of foundations is consistent with the enlightenment ethos in which progress began to slowly eclipse providence, and technology took up the eschatological agenda of making a better world—a man-made and immanent creation. For his part, Serres describes the foundations of Rome not as a static system of support, but rather as a fluid and fecund cultural substrate: “The foundation is the theory or practice of movement. Of fusion and melange. Of the multiplicity of time. Indeed, all foundation is, in the original sense, current. The dike was built between nature and culture. Along it one could easily return.”[38] For Piranesi, the intelligibility of the foundation stones of ancient Rome manifest such a fusion or mélange—a current that renders history immanent and foregrounds the elastic imagination of the architect.

IX. Formations

On a visit to Messina in 1638, Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher witnessed Vesuvius as it began to reverberate and smolder. Overcome by curiosity, he hiked to the rim of the active volcano, and this is what he later wrote about the experience: “When finally I reached the crater, it was terrible to behold. The whole area was lit up by the fires, and the glowing sulphur and bitumen produced an intolerable vapour. It was just like hell, only lacking the demons to complete the picture!”[39] Despite this formative experience, Kircher’s geological imaginings, pursued in his 1664 text Mundus Subterraneus, decidedly tilted more in the direction of nature’s generative capacity than its destructive tendency. In this text, he advanced a hermetic and interiorized worldview of geologic formation: “Kircher repeated an ancient animistic theory important to both British and French materialists that found support among reputable eighteenth-century natural philosophers; namely, that all earthly bodies grow and develop from within.”[40] Kircher’s interest in the vital forces of geologic formation shifted in scale from those forces that animated and shaped the earth’s surface, to those that contributed to “physiographic metamorphoses”—the natural appearance of images and pictograms on stones.[41]

In this scalar shift from the geologic forces animating the subterranean world to the vital stimuli that produce physiographic expressions, Kircher articulates the operations of immanent life. Of these pictorial stones, Barbara Maria Stafford writes:

In this sense, for Kircher, geological configuration is an act of design, and more broadly, within the development of any medium resides this immanent formational impulse. By explicating the process of formation in this way, he strongly anticipates subsequent appropriations of the generative capacities of the natural world.

X. Transmutations

Perhaps nowhere is the thirst for the knowledge of creation more apparent than in the alchemical pursuit of the Philosopher’s Stone, a legendary substance allegedly capable of turning inexpensive metals into gold, and believed to be an elixir of life useful for rejuvenation and possibly achieving immortality. For a long time, it was the most sought-after goal in Western alchemy. Possession of the Philosopher’s Stone, in the form of a yellow, red, or grey powder, was ultimately not about the possibility of accumulated wealth, but rather the power to transform. Precious metals were merely the outcome of the transmutation. The vital force—the life within the stone that facilitated the transformation—was either controlled for purposes of transmutation, or simply possessed as a form of rejuvenation or immortality. The outcome of the experimental procedure was far less important than the instrumental capacity to direct and control the vital force harnessed within the Philosopher’s Stone.

Working together in a laboratory at McGill University in 1898, chemists Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy discovered that radium emits radioactive particles, developing the concept of half-life – a period of time over which half of the substance is emitted and lost.[43] It did not take long for the scientists to make the connection between this material transformation of Radium, with that of their alchemical predecessors. Soddy, who apparently studied alchemy as a hobby, had the temerity to describe the transformation they were witnessing as transmutation. Rutherford responded: “For Mike’s sake, Soddy, don’t call it transmutation. They’ll have our heads off as alchemists.”[44] This tenth and final geological specimen in architecture’s lapidarium, then, brings us full circle. In this case, the life depicted, or perhaps more accurately, the half-life, conforms to Deleuze’s description of life as “matter in variation that enters assemblages and leaves them.”[45]

Conclusion

This foray through ten specimens in architecture’s lapidarium has attempted to advance the following five-point argument. First, a vitalist theme emerges historically at the intersection of architectural, scientific, and philosophical discourse. Second, as a result of these vitalist tendencies, the situation of architecture typically engaged through the category of “site” ceased to be represented as a static, mute, or indifferent condition. Third, vitalism introduces the term “life” as a chronological measure of existence, facilitating the elision of human and geological agency characteristic of the Anthropocene. Fourth, in biology and autobiography, “life” is both the unit of measure and evidence of immanence. The metric of life emerges from the overlap of introverted biological discourse, searching for the smallest unit manifesting life, and the inner investigations of autobiographical work, examining how a given character came into being and how an individual life acquires meaning. Fifth, these ten geological specimens construct a foundation for the understanding of “life” as the measure, and immanence as the operative condition of architecture in the Anthropocene era.

Within architecture’s lapidarium, “life” is explored as an incremental measure of immanence—the life of a resource, the life of a material, the life of a building and the respective lives of its inhabitants, the life of the architectural conceits of “siting” and “material imagination,” and the historiographical life of a disciplinary engagement with stone—all contribute to the constitution of geological life in the Anthropocene. Each of the ten geological specimens represents such an immanent life, and the exploration of each attempted to expose the particular vehicles of immanence that attempt to explicate life’s vital generative forces through the lens of the scientific paradigm, often translating formerly metaphysical concepts into immanent ideas.

In the case of Aldo Rossi’s Scientific Autobiography, geological specimen one, the plan and the autobiography are both examined as vehicles of immanence, through the lens of parallel lives. Utilizing Max Planck’s conservation of energy, Rossi draws his scientific autobiography into dialogue with that of the renowned physicist, as well as Stendhal’s bildungsroman, The Life of Henri Brulard. For Rossi, Planck and Stendhal influenced his architecture through the idea of the conservation of energy and the notion that plans are integral to autobiographical narratives. In drawing this comparison, Rossi moves the possibility of immanent life across three registers: matter’s capacity to conserve energy, the architectural plan’s capacity to capture an event before it unfolds, and the autobiography’s capacity to narrate without definitively concluding. The mythological figures of Isis, the Delphic Oracle, Sisyphus, and Ferdinand Cheval, geological specimen two, consider the recovery of myth’s cyclical narratives in a historical moment in which science’s linear narratives dominate. The re-telling of these narratives through the lens of the scientific paradigm explicates numerous vehicles of immanence. In the case of Isis, the veil that once mediated between the Romantics and nature’s secrets has been removed by the prying analysis of the scientific gaze. As for the Delphic Oracle, her ability to speak for the earth, translating the desires of the gods, is rendered immanent in a process of thesaurization that taxonomically represents difference. In Camus’ hands, Sisyphus becomes a figure through which anthropological identity and geological identity are elided in a single, if not singular, immanent life. While in the urban myth of Ferdinand Cheval, the surrealists identify a material imagination capable of operating between the real and the oneiric.

Viollet-le-Duc’s images of Mont Blanc, geological specimen three, deploy the serial representational strategies of morphology to capture the immanent life of a mountain. In his hands, mathematics becomes a critical tool of abstraction, which leads to speculation about geological decay and formation. The use of taxonomy to represent material phase changes is another vehicle of immanence deployed by Viollet-le-Duc, bringing the fixity of the categories of human knowledge into dialogue with the fluid formation of matter.

Gottfried Semper’s discussion of the techniques of stereotomy in Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts (1860-63), geological specimen four, examines the mathematical operations that impose form on matter as a vehicle of immanence. Semper grounds the epistemology of the techniques of stereotomy upon the ontology of the hearth and foundation walls, theorizing a “crystalline universe” in which the a priori mathematics of geological formation gives rise to architectural tectonics.

John Ruskin’s Stones of Venice, geological specimen five, achieves immanence in the attempt to formulate a universal aesthetic law capable of distinguishing good architecture from “clumsy” copies. Ruskin’s law incorporates the tropes of geological decay (mouldering), mineralogical assaying (touchstones), and geological formation (crystallization) as developmental models ensuring the legitimacy and authenticity of the aesthetic outcomes.

Joseph Michael Gandy’s Architecture: Its Natural Model (1838), geological specimen six, deploys hybrid logics as a vehicle of immanence, operating between the activities of humans and primates, and between the formal logics of geology and architecture. Gandy’s capriccio is a collection of natural wonders that positions geological “life” between the site-specificity of the individual formations and the agency of the human imagination capable of gathering them together. Within this capriccio we witness the seamless merging of natural creation and human production.

In geological specimen seven, Mineral Loads or Veins and their Bearings, from Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, geological life is rendered immanent through the commodification of the earth in terms of its resources and the human labour required to extract them. The project of the Encyclopédie is fully entangled with the instrumentalization of culture and the productive knowledge that it occasions. Within the Encyclopédie, immanence is achieved through the exhaustive cataloguing of disparate techniques of cultural production and their capacity to establish new epistemological horizons.

In Piranesi’s examination of the foundations of ancient Roman culture, geological specimen eight, immanence is located between the almost mythological exaggeration of the “Foundations of the Theater of Marcellus” and the scientific explanation of the construction of the “Mausoleum of Cecilia Matella.” Through the parallel subtractive practices of archeology and etching, life (the life of a building, the life of a ruin) is made immanent in Piranesi’s work, through its analogy with the processes of discovery and representation.

Athanasius Kircher’s Mundus Subterraneus (1664), geological specimen nine, presents an interiorized view of geological formation in which all development emanates from within. In Kircher’s oeuvre, generative creation is mapped from the scale of geological formation to the scale of physiographic metamorphosis, leading to the conclusion that geological configuration is an act of design. Here, the vehicle of immanence resides in the belief that within the development of every medium, a formational impulse can be made intelligible.

Finally, in the transition from alchemical transmutation to nuclear physics, geological specimen ten, the vehicle of immanence is scientific explication. The Philosopher’s Stone was a trope that aligned the possibility of human transformation and change with the possibility for physical change in the material world—it registered a condition of intrinsic development against a condition of extrinsic development, utilizing the observation of one to theorize changes in the other. The deployment of this same term in the context of nuclear physics produced a vehicle of immanence that was ever more interiorized, and ever more radicalized in terms of its implications.

In architecture’s lapidarium, the immanent life of geology is made manifest; the complicity of mineralogical crystallization and human mathematization is expressed; the intelligibility of natural formation and human fabrication is articulated. Within this collection of geological specimens, the intermingling of the earth’s generative forces and human productive ambitions become one, anticipating the architecture of the Anthropocene.

Notes

-

Aldo Rossi, A Scientific Autobiography, trans. Lawrence Venuti (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1981), 1.

-

Stendhal actually wrote two autobiographical accounts, and both were published posthumously. The Life of Henry Brulard was published as a fiction, whereas Souvenirs d’égotisme (The Memoirs of an Egoist), published in 1892, was framed as a more standard autobiographical account. But there is agreement amongst scholars that The Life of Henry Brulard, though posited as a fiction, is the more autobiographically accurate of the two. For the purposes of this argument, the metric of “life,” even Stendhal’s own life, operates seamlessly between fictional and realistic accounts.

-

Erich Auerbach persuasively argues that Stendhal’s writing is not influenced by the pervasiveness of historicism; though he places the events of his life in perspective and is aware of the constant changes around him, this does not result in an evolutionary understanding. Auerbach writes: “[H]e sees the individual man far less as the product of his historical situation and as taking part in it, than as an atom within it; a man seems to have been thrown almost by chance into the milieu in which he lives; it is a resistance with which he can deal more or less successfully, not really a culture-medium with which he is organically connected.” Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1968), 463–465.

-

Rossi, A Scientific Autobiography, 6.

-

Beyle wrote under at least one hundred different pseudonyms, and in this fact resides the relationship between a fluid life and the static name that stabilizes it for a moment in time.

-

Barry Bergdoll, “Of Crystals, Cells, and Strata: Natural History and Debates on the Form of a New Architecture in the Nineteenth Century,” Architectural History 50 (2007): 6.

-

Martin J. S. Rudwick, Bursting the Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), 9.

-

Ibid.

-

Gilles Deleuze, Pure Immanence: Essays on a Life, trans. Anne Boyman (New York: Zone Books, 2001), 29.

-

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 53.

-

Ibid., 54.

-

Giorgio Agamben, Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy, ed. and trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 223. Agamben goes on to stipulate that “the colon represents a dislocation of immanence in itself, a characterization suggesting that this crossing or passing is not relational, but rather autonomous.

-

Ibid., 224.

-

Ibid., 234.

-

Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1956), 738.

-

Karsten Harries, The Meaning of Modern Art (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 50.

-

Steven Connor, Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 52.

-

Page duBois, Sowing the Body: Psychoanalysis and Ancient Representations of Women (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 107–108. Elsewhere, duBois describes thesaurization in this way: “It locates the female as a potential for producing goods or protecting them. She becomes the locus of inscription, the folded papyrus that signifies the potential for deception.” See: Page duBois, “The Platonic Appropriation of Reproduction,” in Feminist Interpretations of Plato, ed. Nancy Tuana (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994), 139.

-

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, trans. Justin O’Brien (New York: Vintage International, 1983), 121.

-

See Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Mont Blanc: A Treatise on Its Geodesical and Geological Constitution; Its Transformations; and the Ancient and Recent State of Its Glaciers, trans. B. Bucknall (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1877). Originally published in French in 1876.

-

Deleuze, Pure Immanence, 26.

-

Histoire de l’habitation humaine, depuis les temps préhistoriques jusqu’à nos jours (1875), published in English in 1876; Histoire d’un dessinateur: comment on apprend à dessiner (1879); and Histoire d’une maison (1873).

-

Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution, trans. Arthur Mitchell (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1983), 302. (First published in French in 1907, and in English in 1911.)

-

John Rajchman, introduction to Pure Immanence: Essays on A Life, by Gilles Deleuze (New York: Zone Books, 2001), 13. Rajchman writes: “For immanence is pure only when it is not immanent to a prior subject or object, mind or matter, only when, neither innate nor acquired, it is always yet ‘in the making;’ and ‘a life’ is a potential or virtual subsisting in just such a purely immanent plane.”

-

Gottfried Semper, Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts or, Practical Aesthetics, trans. Harry Francis Mallgrave and Michael Robinson, Getty Texts and Documents Series (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Center, 2004), 726.

-

Semper, Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts, 728.

-

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice (London: George Allen, 1896), 52.

-

Ibid., 48.

-

Brian Lukacher, Joseph Gandy: An Architectural Visionary in Georgian England (London: Thames and Hudson, 2006), 189.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Deleuze, Pure Immanence, 29.

-

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto (London: Verso, 1998), 40.

-

In The Will to Power, Nietzsche describes the monster of energy as follows: “And do you know what ‘the world’ is to me? Shall I show it to you in my mirror? This world: a monster of energy, without beginning, without end; a firm, iron magnitude of force that does not grow bigger or smaller, that does not expend itself but only transforms itself; as a whole, of unalterable size, a household without expenses or losses, but likewise without increase or income; enclosed by ‘nothingness’ as by a boundary; not something blurry or wasted, not something endlessly extended, but set in a definite space as a definite force, and not a space that might be ‘empty’ here or there, but rather as force throughout, as a play of forces and waves of forces, at the same time one and many, increasing here and at the same time decreasing there; a sea of forces flowing and rushing together, eternally changing, eternally flooding back, with tremendous years of recurrence, with an ebb and a flood of its forms; out of the simplest forms striving toward the most complex, out of the stillest, most rigid, coldest forms striving toward the hottest, most turbulent, most self-contradictory, and then again returning home to the simple out of this abundance, out of the play of contradictions back to the joy of concord, still affirming itself in this uniformity of its courses and its years, blessing itself as that which must return eternally, as a becoming that knows no satiety, no disgust, no weariness: this, my Dionysian world of the eternally self-creating, the eternally self-destroying, this mystery world of the twofold voluptuous delight, my ‘beyond good and evil,’ without goal, unless the joy of the circle is itself a goal; without will, unless a ring feels good will toward itself—do you want a name for this world? A solution for all of its riddles? A light for you, too, you best-concealed, strongest, most intrepid, most midnightly men?—This world is the will to power—and nothing besides! And you yourselves are also this will to power—and nothing besides!” Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, trans. Walter Kaufman and R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 549–550.

-

Michel Serres, Rome: The Book of Foundations, trans. Felicia McCarren (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991), 259.

-

Barbara Maria Stafford, Body Criticism: Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991), 58.

-

Stafford, Body Criticism, 70.

-

Serres, Rome, 275.

-

Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 186.

-

Barbara Maria Stafford, “Characters in Stones, Marks on Paper: Enlightenment Discourse on Natural and Artificial Taches,” Art Journal 44, no. 3 (Autumn 1984): 233.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid., 235.

-

David Orrell, Truth or Beauty: Science and the Quest for Order (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 72.

-

Ibid.

-

Bennett, Vibrant Matter, 54.