7. Face Race

Defacing and Facing Humanity

The human race is facing extinction. One might even say that there is a race towards extinction, precisely because humanity has constituted itself as a race. The idea of a single species, manifestly different but ultimately grounded on a single human race of right and reason, has enabled human exceptionalism, and this (in turn) has precluded any questioning of humanity’s right to life. In actuality humanity is not a race; it becomes a racial unity only via the virtual, or what Deleuze and Guattari describe as a process of territorialization, deterritorialization and reterritorialization. In the beginning is what Deleuze and Guattari refer to as the ‘intense germinal influx,’ from which individuated bodies (both organic and social) emerge. Race or racism are not the results of discrimination; on the contrary, it is only by repressing the highly complex differential forces and fields that compose any being that something like the notion of ‘a’ race can occur. This is why Deleuze and Guattari argue for a highly intimate relation between sex and race: all life is sexual, for living bodies are composed of relations among differential powers that produce new events; encounters of potentialities intertwine to form stabilities. Such encounters are desiring or sexual because they occur among different forces that create new and dissimilar outcomes. If sex and desire refer to the relations among different quantities of force, race and races occur when those productions of differences are taken to be differences of some relative sameness. In the beginning is sex-race or race-sex: the encounter of different potentials to form new emergent (relative) identities. Race and racism occur through such intersections of desire, whereby bodies assemble to form territories. All bodies and identities are the result of territorialization: so that race (or kinds) unfold from sex, at the same time that sexes (male or female) unfold from encounters of genetic differences. All couplings are of mixed race.

It is through the formation of a relatively stable set of relations that bodies are effected in common. A body becomes an individual through gathering or assembling (enabling the formation of a territory). A social body, tribe or collective begins with the formation of a common space or territory but is deterritorialised when the group is individuated by an external body—when a chieftain appears as the law or eminent individual whose divine power comes from ‘on high.’ This marks the socius as this or that specified group. Race occurs through reterritorialization, when the social body is not organized from without (or via some transcendent, external term) but appears to be the expression of the ground; the people are an expression of a common ground or Volk. The most racially determined group of all is that of ‘man’ for no other body affirms its unity with such shrill insistence. ‘Humanity’ presents itself as a natural unified species, with man as biological ground from which racism might then be seen as a differentiation.

The problem with racism is neither that it discriminates, nor that it takes one natural humanity and then perverts it into separate groups. On the contrary, racism does not discriminate enough; it does not recognize that ‘humanity,’ ‘Caucasian,’ or ‘Asian’ are insufficiently distinguished. Humanity is a generality or the creation of a majority of a monstrous and racial sort. One body—the white man of reason—is taken as the figure for life in general. A production of desire—the image of ‘man’ that was the effect of history and social groupings—is now seen as the ground of desire. Ultimately, a metalepsis takes place: despite surface differences it is imagined that deep down we are all the same. And because of this generalizing production of ‘man in general’ who is then placed before difference as the unified human ground from which different races appear, a trajectory of extinction appears to be relentless. Man imagines himself as exemplary of life, so much so that when he aims to think in a post-human manner he grants rights, lifeworlds, language and emotions to nonhumans. (And when ‘man’ imagines animal art or language he does so from the perspective of its development into human art and language; what he does not do is animalize human art, seeing art not as an expressive extension of the body, but as an expressive matter in its own right.) Man’s self-evident unity, along with the belief in a historical unfolding that occurs as a greater and greater recognition of identity (the supposed overcoming of tribalism towards the recognition of one giant body of human reason) precludes any question of humanity’s composition, its emergence from difference and any further possibility of its un-becoming. Humanity has been fabricated as the proper ground of all life—so much so that threats to all life on earth are being dealt with today by focusing on how man may adapt, mitigate and survive. Humanity has become so enamored of the image it has painted of its illusory beautiful life that it has not only come close to vanquishing all other life forms, and has not only imagined itself as a single and self-evidently valuable being with a right to life, it can also only a imagine a future of living on rather than face the threat of living otherwise. Part of the problem of humanity as a race lies in the ambivalent status of art, for art is the figure that separates white man par excellence: humanity has no essence other than that of free self-creation, all seemingly different peoples or others must come to recognize their differences as merely cultural, as the effect of one great history of self-distinction. However, if art were to be placed outside the human, as the persistence of sensations and matters that cannot be reduced to human intentionality, then ‘we’ might begin to discern the pulsation of differences in a time other than that of self-defining humanity. Art would not be an extension of the human, a way in which man lives on and creates himself through time. Art would be bound up with extinction, signaling the capacity of matters to insist and persist beyond any animating intent.

Far from extinction or human annihilation being solely a twenty-first century event (although it is that too), art is tied essentially to the non-existence of man. Art has often quite explicitly considered the relation between humanity and extinction. For it is the nature of the art object to exist beyond its originating intention, both intimating a people not yet present (Deleuze and Guattari 1994, 180), and yet also often presupposing a unified humanity or common ‘lived.’ Wordsworth—yes, Wordsworth!—was at once aware that the sense of a poem or work could not be reduced to its material support, for humanity is always more than any of the signs it uses to preserve its existence:

If the archive were to be destroyed, would anything of ‘man’ remain? Art gives man the ability to imagine himself as eternally present, beyond any particular epoch or text, and yet also places this eternity in the fragile tomb of a material object: ‘Even if the material lasts only for a few seconds it will give sensation the power to exist and be preserved in itself in the eternity that coexists with this short duration’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1994, 166). ‘Man’ as a race (as a unified body imagining himself as a natural kind) is essentially tied to extinction: for man is at once an ex post facto or metaleptic positing of that which must have been there all along, awaiting eternal expression. At the same time ‘man’ is also that being who hastens extinction in general by imagining himself as a single tradition solely worthy of eternal life, stamping the world with his own image. This unified humanity that has become intoxicated with its sense of self-positing privilege can only exist through the delirium of Race, through the imagination of itself as a unified and eternal natural body:

Racial delirium is not only a passage through differential flux from which identity emerges; it also entails that ‘we destroy civilizations’—affirming the potentiality of reducing any produced culture or tradition to ruins. Man exists above and beyond any particularity; as one grand racial unity, he is that through which cultural distinction emerges. If racial delirium occurs as an affirmation of the possibility of anything becoming extinct, racism is a neurotic grip on survival. Racism—including, and especially, the affirmation of ‘man’—is a repression of racial delirium; racial delirium would open up to all the differences and intensities beyond any unified or generic ‘man.’ By contrast, racism affirms one great unity—the properly human—in which various kinds might be seen to differ by degree, being more or less human. Humanity is always a virtual production or fabrication that posits itself as ultimate actuality, occluding the differentials from which it emerges.

The fabrication of man as a race that at once enables the lure of essential unity, and yet places that unity in the fragile monuments of art today (in the twenty-first century) faces the actual threat of extinction. Given that threat, how might art adjust to a milieu of imminent, probably certain, disappearance? How might this race that has for so long surrounded itself with art, and mirrored itself in art, open out to the world upon which it depends but which it has nevertheless almost annihilated? How does the human race turn from mirroring itself, enclosing itself in the cave of its own images, to thinking its inextricable intertwining with fragile life?

These questions are not new. All art has the problem of extinction and race at its core.

Any sentence that begins with ‘All art…’ needs to be treated with extreme suspicion. The logic of racism, after all, has always defined the properly human from a single moment—deep down they are all (or should be) just like ‘us.’ And, as already mentioned, the figure of art is crucial to this unifying lure: deep down we are all human, all the same, and express ourselves differently in the grand tradition of human art. Such claims are less often made by art historians than they are by philosophers, who are fond of speaking of art as such, or art in general, or the essence of art, and who usually deploy such concepts to smuggle in normative concepts of humanity. When a philosopher defines what art is he is usually making a moral claim about life, and this is especially so when philosophy seemingly detaches itself from the assumptions of normativity, when philosophy speaks for man in general. Kant’s insistence on aesthetic judgment as reflective, presupposes Western art practices of framed and detached art objects: man realizes that he is not just a physical body, but a subject who can feel himself as a creative being responsible for the reason of the world. When Jacques Derrida affirms that ‘literature is democracy’ (Thomson 2005, 33; Kronick 1999, 166) he includes all literary practice under a high modernist norm of framed voice (art is not what is said, but a presentation that there is ‘saying’); when Theodor Adorno (2004), more explicitly, shows the aesthetic as properly disclosed in modernist formalism he allows art in general to be oriented towards the disjunction between concept and reality; various Marxisms or historicisms will begin an account of art in general from this or that exemplary object (the social novel, Greek tragedy, postmodern reflexivity). Deleuze and Guattari seem both to fall into this (possibly unavoidable) universalizing tendency with their distinction between an art of affects and percepts and a philosophy of concepts. And yet their insistence that art emerges from a pre- or counter-human animality and that this ‘art’ lies in the capacity of sensations to persist in themselves, opens the thought of an inhuman time, and an eternity outside man (Deleuze and Guattari 1994, 182). This is why, also, they pay so much attention to the twinned concepts of race and face: for it is art that at once forms the figure of a common humanity (man as homo faber), at the same time as the resistance and decay of art objects opens life and creation to temporalities beyond those of a self-legislating humanity.

It is most often philosophers, determined to secure a domain of life that is not yet submitted to convention, instrumentality, recognition, opinion, or assumptions of human nature, who will find in art as such that which precedes, exceeds or disturbs given systems. Art either offers us the capacity to reflect upon the worlds ‘we’ have formed (Habermas 1987), or, art brings ‘us’ back once again to humanity’s eternal capacity to be nothing other than the image it creates from itself (Agamben 1999, 68). But there are two ways this eternity might be thought: as humanity’s destiny—man as the capacity to create the thought of the universal—or as humanity’s annihilation: for perhaps it is not man (or man alone) that witnesses or evidences a temporality outside organic specified life. If art is necessarily always concerned with annihilation and specification (or the production of species, and the persistence of sensations beyond the life of the creator) then any claim that art is essentially or eternally of a certain mode belies art’s distinct fragility. That is, the claim to something like art in general reinforces the sense of man or humanity in general, and occludes what Deleuze and Guattari have presented as the animality of art, its existence in pure matters of sensation.

When Deleuze and Guattari [1994, 165] argue for art as the preservation of sensations that exist before man—sensations that persist in themselves—they go a long way to destroying the race of man.

Art is not the expression of humanity, in general, but the destruction of any such generality through the preservation and temporality of the ‘nonorganic life of things’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1994, 180). Art, traditionally conceived, has been racial in a double sense: it offers figures of man in general (always—in Western art—the white face of the subject); and is then archived as the expression of a humanity that comes to know and feel itself through the creation of its own pure images.

Art, Face, Race

Art is always the preserving of a sensation that is of its time, but that is submitted to existence for all time. If art is to figure something like ‘the human’—and if the human is, philosophically, an openness to world that is given best in the face—then it must always do so through the material figure of some specified head. Emmanuel Levinas’s argument that the face is singular, and that the singular relation to any face disrupts a logic of calculation and specification, is an extreme philosophic argument; it takes up the premise of philosophy—of a radical transcendence that is not of this world of beings—and yet returns that transcendence to the privileged body of man:

Levinas’s elevation of the face relies on an experience of a singularity that would be liberated from all generality, that would not be a specification of this or that universal type. Levinas’s appeal to the face is at once non-semantic, for the face disrupts generality and communication or shared notions of what counts in advance as human; the face appears in its singularity as this face, before me, here and now. If, however, such a face were to be figured in art it would need to take on some specification, where specification is always of the species or race. A face ‘as such’ without species might be thought but it could only be figured through this or that concrete head. Even when it does not figure human bodies, persons or faces, art is always about face and always about the extinction of species. It is always a presentation of this earth of ‘ours’ witnessed from our race: ‘All faces envelop an unknown, unexplored landscape; all landscapes are populated by a loved or dreamed-of face, develop a face to come or already past’ (Deleuze and Guattari 2004b, 191). So there are two twinned (yet necessary) impossibilities. First, a work of art can live on, as eternal and monumental, only if it takes on a material support: my thoughts can be read after my life only if I inscribe them in matter. And yet, second, that matter is also essentially fragile, corruptible and subject to decay. A face—or the witnessing of the subject in general—can only occur through some racialised head: I can only imagine humanity in general, as spirit, through the species. The eternal—the sense of art, the subject of the face—is always constituted through this object, this head. The logic that intertwines face, race and art is the logic of life: a unified body or species can only occur through persisting beyond individual bodies—a race is like an artwork or monument, surviving beyond individual life—and yet, such persisting unities also only survive through variation. A race or species varies and opens to other differences in order to live on, just as the individual human subject can persist through time, beyond himself, only by supplementing himself through the matters of art.

A work of art is only a work if it has taken on some separable and repeatable form, but it is just that taking on of a body (or incarnation) that also suffers a process of decay. That is, just as the art object is possible because of a selection of matters that will both resist dissolution (in the short term) and be exposed to inevitable decay, so the bounds of a race are possible only because of a specification that requires an ultimately annihilating variability; a race or species is possible only because of something like an art in life, a variability that both enables the formation of living borders but that also entails the annihilation of bounds. A race is at once the gathering of sameness, a certain genetic continuity, and an openness to difference—for a race continues through time via sexual variation.

In the remaining sections of this chapter I want to explore two ideas about extinction and race in relation to art works that will allow us to look at the ways in which all life is oriented to an oscillation between extinction and specification (or ‘raciation’), and that this leads to an impure border between the faces of philosophy—or the idea of a humanity as such—and the heads of art, or the material figures through which that humanity is given.

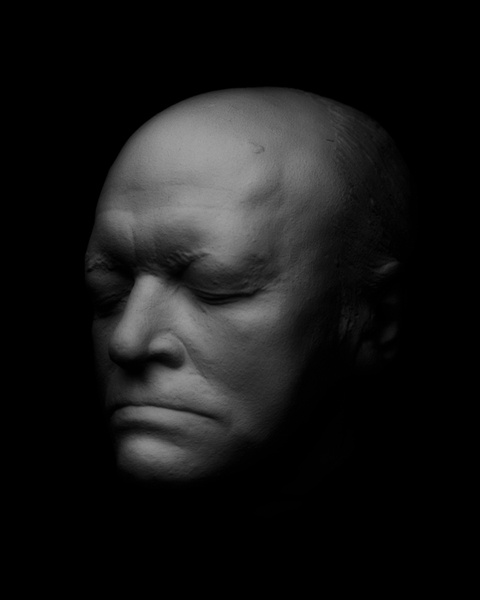

As a preliminary opening to these two ideas of race and extinction I want to consider three visual images, the first of which is the smiley face that came to stand for acid house culture, while the second is William Blake’s death mask refigured first by Francis Bacon’s 1955 ‘Study for Portrait II (after the Life Mask of William Blake),’ and second by the contemporary Edinburgh photographer Joanna Kane (Kane 2008). All of these images, in different ways, problematize the distinctions between the face and the head, between philosophy and art, or between species-survival and extinction. If we want to consider something like a pure form of the face (theorized philosophically) then we could turn to Levinas’s detachment of the face from all generality, calculation, mediation and specification: for Levinas a face is not a head. The latter is a body part, and might also figure something like the biological human species to which ‘we’ would owe certain allegiances and contracts. On a bodily, psycho-physical or (for Levinas) non-ethical level, it is because others have bodies like mine that I enter into certain sympathies, and this would allow ‘us’ to maintain ourselves in relation to external threats and a milieu of risk (so the head would also signal something like Bergson’s ‘morality,’ which is a bonding formed through relative likeness [Bergson 1935]). For Levinas, all philosophy that has been grounded on being, or that has tried to determine some ideal of justice, humanity and order in advance emanating from a general physical humanity, annihilates the radical singularity of the face. It is the encounter with this face, here and now, that disrupts convention, sign systems, repeatability and doxa; it is this singular face that prevents the reduction of otherness to an event within the world. The face enables us to pass from (or through) the heads that we recognize as part of a common species, to the other whom we can encounter but never know. Or, in Bergson’s terms: from something like a common morality of humanity premised on a specified kind, one would pass to the thought of a virtual, not yet present and singular other.

The face would give us something like pure life: not the form or matter that one recognizes as the same through time and that is subject to decay and exposure to risk, but the animating spirit of which matter is a sign. The face for Levinas is, after all, not a sign or mediation of humanity so much as an experience or rupture with all mediation and sense. (The same applies for those who invoke his work today, amid conflicts among peoples [Butler 2006, 133].) Life, however, is never pure and its processes of variation and creativity are known only through the relative stability of bounded forms. These forms and bounded beings are perceived as the beings that they are only by reducing the intense fluctuations and differences into ongoing and recognizable figures. At the other end of the spectrum from the pure life of a perception that is not yet frozen or determined into any relatively inert figure is the mere head. If the head for Deleuze and Guattari occurs with a pre-modern tribal individuation that is not yet that of humanity, it is possible to see this head again today in the post- or counter-human head of the smiley face. So lacking in distinction that it has neither race, nor humanity, nor artfulness, the smiley face signals loss of life (having become a punctuation mark in emails and text messages: ‘:)’). It is the retreat from specification and the removal of any definitive body—anything that would allow for engaged sympathy—that makes the smiley face at once the most vulgar of heads, as though even the primitive animal totem heads (or portraits commissioned through patronage) were still too singular to really enable the joys of a loss of face.

In two recent books the neuroscientist Susan Greenfield has commented on the contemporary problem of meaning, sensation and identity. Drugs that work to overcome depression may operate by relieving the brain of its syntactic work, allowing the body to experience sensation as such without laboring to tie it into significance. A depressed person cannot, Greenfield argues, simply enjoy a sip of espresso, the feel of sunshine on the skin or the sound of a flowing stream (Greenfield 2000). The depressive is focused on meaning or connection, tying sensations into a resonant whole, and cannot therefore experience the senseless ecstasy of sensation as such. An experience is meaningful if it is placed in the context of past encounters and future projects, but a certain joy is possible only if that neural network of sense is also open to sensation. One must be a self—having a certain face and singularity that defines one as who one is in terms of one’s projects—but one must sometimes also be just a head: a capacity to feel or be affected without asking why, or without placing that sense in relation to one’s own being and its ends. Greenfield’s more recent book, ID, has—despite her earlier recognition that we sometimes need to let go of identity and meaning—lamented what she sees to be an attrition of our neural architecture (Greenfield 2008). While the current drug and computer-fuelled retreat from syntax and recognition—and its accompanying sense of self—has its place, contemporary culture’s focus on flashing screens, disconnected sensations and immediate intensities is hurtling in an alarming manner to a total loss of face. There is a widespread loss of being someone, and a disturbing tendency towards being ‘anyone.’

That such a process of neural extinction accompanies species extinction is not a mere coincidence, and that such a movement towards not being someone is symbolized by the smiling head of ecstasy use should give us pause for thought. As the species comes closer to the extinction that marked its very possibility as species, it has retreated more and more into its own self-identity, becoming more and more convinced of the unity of race (the humanity of man in general). One could only become this or that marked race—especially the race of man—by closing off absolute difference and englobing oneself into a determined and self-recognizing kind: ‘When the faciality machine translates formed contents of whatever kind into a single substance of expression, it already subjugates them to the exclusive form of signifying and subjective expression’ (Deleuze and Guattari 2004b, 199). Is it any surprise that today, confronted with actual species extinction, ‘man’ ingests drugs that relieve him of meaning, buys screens that divert his gaze away from others, and consumes media that pacify him with figures of a general and anodyne ‘we’? Is this loss of face something that is accidentally destructive, or could we not say that the face of man emerges from such self-enclosure? Is not the grand scene of Levinas’s ethics—one face to another without intrusion of a third or any other world—not the mode of coupling that has led to the earth’s defacement? Today’s culture of self-annihilation—an overcoming of face, sense and bounded recognition—may not be as lamentable as Greenfield and others suggest. It may be a perfectly inhuman (and therefore wonderful) response to a world in which the value and art of one’s species is no longer unquestionable. Is face, human face in its radical distinction and immateriality, really what one wants to save?

Acid house visual and aural culture, apart from being signaled by the smiley face, rely on an elimination of a time of development and figuration in favor of a time of pulsation. Music of this style, along with trance and later forms of dubstep and brostep, destroy the man of speech and reason for the sake of sensations liberated from humanity. Not only do the drugs that accompany trance and house music allow for the experience of sensation without a framing of sense, the music is characterized by instrumental—usually digitally synthesized—repeated chord sequences, with infrequent and non-complex modulations, pulsing rhythms and uses of language that are sonorous rather than semantic. Visuals that accompany this music are not so much abstract as minimal, not geometric forms and figures but intensities of light and color. That this movement of acid house is part of a broader tendency towards loss of face is signaled by the smiley head it takes as its totem, by the general culture of counter-syntax described by Greenfield, and by the strange neural tie between the face and specification. What such late capitalist events disclose is what Deleuze and Guattari refer to as a ‘higher deterritorialistion;’ there is not a movement back to the one single ground of humanity, but a creative release that opens out towards a cosmos of forces beyond humanity. More specifically one might note, then, that it is not by inclusion or extension of the categories of rights and humanity that one might overcome the intrinsic racism (which is also a species-ism) that regulates the concept of man. Rather, it is by intensifying sensations that one is liberated from the face of the signifying subject, opening forces to the inhumanity of the cosmos:

One of the most commonly cited neural disorders in much of the current popular literature regarding the brain is Capgras syndrome, where a patient without any delusion or loss of cognitive function, sees a close relative but then claims that this relative is an alien or imposter (Feinberg and Keenan 2005, 93). (This would be the opposite tendency of ecstasy culture where every stranger appears as a beloved.) What is missing is not any visual or cognitive input but affective response: if the emotional intensity or affect is not experienced then I claim—despite all evidence to the contrary—that this is not my mother, or child or partner. This syndrome has been widely cited in order to claim that we are not solely or primarily cognitive beings, and that our relation to others requires an affective response to their visual singularity—not simply the knowledge or recognition of who they are. This might seem both to support and refute the Levinasian face. On the one hand it seems that—despite Levinas’s claims that the face of the other makes an impelling claim on me—it is really only certain faces with a specific visceral genealogy pertinent to our own being that are truly experienced as faces; everyone else is a mere head. On the other hand, it also appears that the face is not one object in the world among others, not reducible to a knowable and identikit type, for faces are radically singular. Faces engage affective registers that cannot be overridden by cognitive or simply visual inputs. A face at once has no race, for if I see this other as a face then I am devoted to an affective response that has nothing to do with general (or genetic) specifications. On the other hand, the face is absolutely racial, for there is no such thing as the face of humanity in general, or a global fellow feeling; the face that engages me, disturbs me and transcends cognition is the face that is bound up with my own organic and specified becoming. The face is at once that which is radically exposed to extinction, given that I experience as face only those heads bound up with my world, time and life. At the same time, the face appears to be quite distinct from organic survival; the body of the other person is before me, and yet something is missing. The affect, which is not a part of their body but is bound up with their capacity to be perceived in a certain manner, is what marks their singularity:

One response to the border of the face—to this strange body part that is at once an organic head and also a marked out, fragile and exposed singularity—is a form of willed extinction. If there has been a tradition of art dominated by portraits, signatures, leitmotifs and claims to radical distinction and living on, there is also a counter-tradition of the head rather than the face, concerned with annihilation, indistinction and becoming no one. Faced with the all too fragile bounds of one’s specified being one could either cling more and more desperately to one’s englobed humanity—asserting something like Levinas’s pure face as such—or one could confront the head head-on.

Both Francis Bacon’s portrait of Blake and the contemporary Scottish photographer Joanna Kane’s photograph are taken from William Blake’s death-mask. Blake, perhaps more than any other artist, exposed the impure logics of extinction, specification and art. Resisting an increasing culture of commodification and the annihilation of the artist’s hand, Blake would not submit his poetry to the printing press, nor subject his images to the usual methods of reproduction. Determined not to lose himself in the morass of markets, mass production and already given systems, Blake engraved every word of his poetry on hand-crafted plates, colored every page with his own hand, invented his own mythic lexicon and gave each aspect of every one of his ‘characters’ a distinct embodied form. As a consequence of seizing the act of production from the death of general systems, and directly following the assertion of his own singularity against any general humanism, Blake’s work is more subject to decay, extinction and annihilation than any other corpus. Because Blake resisted the formal and repeatable modes of typeface, and because he took in hand his own creation of pigments and techniques of illuminated printing, it is not possible to detach the pure sense or signature of Blake’s work from its technical medium. The more Blake took command of technicity or matter—the more he rendered all aspects of the work artful—the more exposed his work was to the possibility of annihilation. It was because Blake’s work was so specific, so distinct, so committed to the living on and survival of the singular, that it was also doomed to a faster rate of extinction. (Blake’s work can never be fully reproduced or anthologized.)

Similarly, one can note that it is because it was so masterful at survival, at securing the sense of itself and its worth as a species, that humanity as a race faces accelerated destruction.

Both Bacon and Kane depict Blake not through the surviving portrait, but through the death-mask. If the portrait is one of the ways in which the head is framed, signed, attributed and placed within a narrative of artist as author, creator and subject of a world of intentionality that can be entered by reading and intuition, this is because the face of the portrait is tied to an aesthetics of empathy, in which the hand of the artist is led by the idea of a world that is not materially presented but that can be indicated or thought through matter. In this respect the portrait can be aligned with what Deleuze refers to as a history of digital aesthetics, in which the hand becomes a series of ‘digits’ that in turn allows the world to be visualized, not as recalcitrant matter, but as a quantifiable mass in accord with the eye’s expectations (Deleuze 2005, 79). The digital—as universalizing and generalizing of the world—therefore presupposed what Derrida referred to as a Western assumption of a pre-personal ‘we’—the humanity in general that would be able to view and intuit the sense that is before me now (Derrida 1989, 84). For all its supposed resistance to mediation, representation and a history of Western being that has reduced the event of encounter to a general ‘being’, Levinas’s ‘face’ is insistent on an immediate relation to otherness that is not diverted, corrupted or rendered opaque by the decay-prone flesh of the head. What sets the aesthetics of empathy, which would discern a spirit in the bodily figure, apart from the aesthetics of abstraction is just this positing of an immateriality that transcends matter. It is the other, given through the face, whose presence is not arrived at by way of analogy or concepts. This is possible only if all those matters that tie a subject to specification and therefore certain extinction are deemed to be transparent or external to some pure otherness as such, to some pure face that is not corrupted by the head.

The portraits of Blake, like the sense of Blake’s work in general, do indeed survive and circulate beyond the author’s living body. Even so, that face of Blake and the sense of the work that survives beyond decaying matter are possible and released into the world only through a matter that is intrinsically self-annihilating. An aesthetics of abstraction, in contrast with empathy, is possible through a production, from matter, of pure forms; abstraction constitutes formal relations distinct from the singular, localized and subjective experiences of living organisms. One might therefore say that it is only through racial delirium—passing through and annihilating all the species of man—that one finds something other than racism, or man as he properly is. This might effect an ‘about-face’. Blake’s work already confronted this relation between, on the one hand, discerning the world as possessed of spirit (a world of innocence in accord with an ultimately human face), and, on the other hand, a world of matter devoid of any life other than its reduction to pure forms of digits (the world of ‘single vision and Newton’s sleep,’ where experience knows in advance all that it will encounter). In his illuminated printing and engraving techniques Blake’s works confronted the resistance of the hand in relation to a matter that was neither pure form, nor living spirit, but yielded something like an analogical aesthetics—the genesis of forms and life from the chaos of materiality. One could refer to this as a radically haptic aesthetic in which the eye can see the resistance of form emerging from matter, feeling the resistance of (in Blake’s case) the hand, and in the case of the deathmask the curvature of the head (Colebrook 2012A).

Bacon’s paint adds its own flesh of color to the form of the mask, while Kane’s highly finished photography renders the material object spiritual, not by gesturing to the face but by granting the matter itself its own luminosity. The visual surface of the photgraph, rather than the gazing face of the portrait, seems to posses at once its own spirit and its own temporality, specification and line of duration. It is matter itself, and not the living form it figures, that seems to endure opening its own line of survival, extinction and specification. Kane’s faces-heads are higher deterritorializations in two senses. The face that enables empathy and alterity becomes a head again, but not a head of the living organism so much as a material artifact of matters that are themselves expressive. The art object that would seem to signal the human organism’s potentiality to free itself from mere biological life, to create that which endures beyond its own being, itself shows all the signs of material fragility, exposure and annihilation. Philosophy finds faces in art; art is that creation of a signification of a sense beyond any body, of an endurance liberated from the instrumentality of the human organism. But there is always something of the crumbling, decaying, unspecified head in the faces of art.