“What I Could Lose”: The Fate of Lucia Moholy

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

How to write about Lucia Moholy? There are many stories I could tell. There is the story of her life as a photographer and writer, a truly modern, international woman who came of age with the First World War. Or the story of her life with her husband, the famous teacher, photographer, painter, typographer László Moholy-Nagy and their years together at the Bauhaus. Or the story of her life in exile and failed attempt to immigrate to the United States during World War Two. I knew from the start I would like to tell a little of all these things, but the question I struggled with when I thought of Lucia was, how?

How do I do justice to this life that is no longer and that I never met, and yet means so much to me? The most honest way I could think to do this is also perhaps the one that makes her the most vulnerable. It is to tell about Lucia the way she told about herself in private, in her diaries, letters, and photographs. So I will wake her archive for a while here and ask it to speak through me, if I may.

But from whom shall I ask permission? I have no right to channel her voice, perhaps, but I see here my chance to liberate her for a moment from a world that requires footnotes, to speak outside the sterile language of the academy to tell the story of a woman who was due far more respect than she has yet been given.

How to write about Lucia Moholy? The following is but my interpretation of how Lucia wrote herself.

Looking through László Moholy-Nagy’s preserved materials at the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin last year, I found myself persistently drawn to the moments when Lucia seeped through, in lines of letters or in photographs. I am writing a dissertation that describes the relationships of many men; at first that was accidental, or put another way, lazy. History has provided us with a long line of men to uphold and admire. One must look harder to uncover the legacy of the capable women among their ranks. Oddly enough, I did not wonder where the women were early on, and the consequence has been that I have sat for years in front of box upon box of archival materials, growing ever wearier at the lack of representation of someone somewhat like myself in the lives I sift through. It is as Roxane Gay describes the experience of watching television as a black woman in America, predictably viewing a sea of white faces acting out narratives devoted to telling the stories of men’s lives. “I enjoy difference,” she writes, “but once in a while, I do want to catch a glimpse of myself in others.”

Finding Lucia in the archive was like catching a glimpse of myself. I took to her story personally; she became my companion as I mined a historical record that has not deigned to preserve many of history’s women. In the archive, I poured through boxes of letters sent from and received by several of the big names at the Bauhaus—László, Walter Gropius, Herbert Bayer, on and on—and it was only in the form of a secretary or in correspondence between the wives that a female voice came through. But many of these women were great artists in their own right, and some do have their own (if smaller) archives. Looking through Lucia’s came to be how I would reward myself after weeks spent with the Männer. I’d look at snatches from her collection, following my personal inclinations rather than any real scholarly purpose. I read through her diaries, written as a young girl in Prague, and then later, as a woman at the Bauhaus, married to one of the school’s most esteemed “masters.” And I looked through her photographs, taken of and by herself. I read her letters. She became no longer a peripheral interest but a central occupation, despite the fact that she did not fit into the research project I’d been sent to Berlin to undertake.

I’d stumbled upon her and looked into her life; an accidental intimacy.

Before she was Lucia Moholy, she was Lucy Schulz, a girl growing up German in Prague during the final years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in a nonpracticing Jewish family. (Franz Kafka, eleven years her elder, grew up in similar circumstances in the same place.) In the archive, there are two diaries from this period that span the years 1907–1915. The first is brown and leather-bound with a silver clasp that can be locked, the word Tagebuch scrawled in gilded script across the front. The second also has a clasp for lock and key but is less sumptuous in style, with a simple textile cover of woven yellow and green.

In one entry from May 10, 1907, at the age of thirteen, Lucia recounts the return of her father from a trip away from Prague: “Today Papa came home! He looked fabulous. We all waited for him at the Franz Josefbahnhof. [Now simply called the Main Train Station, in Czech.] Uncle Wilhelm too. Papa brought us some really beautiful things.” Her artistic inclinations are already apparent, as she goes on to sketch in ink a table replete with all the fine things her father brought home from his travels. On the table sits a pair of long gloves for her grandmother, some delicate combs for her mother (who is reported to have balked at their extravagant price), a necklace and purse for Lucia, and books for her brother. The edge of an open door is drawn in the lower left corner of the picture, and I am there in the invisible doorframe, peeking into this room and its tableau of bourgeois comforts, but also, more generally, into this life. I am what would have been my own teenaged worst nightmare: the stranger that finds the diary and reads what’s inside, its raw, unfiltered contents laid bare to the voyeur. In the archive, I feel viscerally my status as intruder, even as I do not stop turning the pages.

Lucia’s diaries from these years are not risqué, but that can hardly be the point. They are her words, and they are not for me. Guiltily then, I offer a little more here on what the diaries contain: She reports on her English-language pen pals in Indiana. She quotes from Thomas Mann, Leo Tolstoy, and Auguste Rodin, and transcribes a Beethoven sonata (Lucia, too, seemed to lack female models of intellectual and artistic excellence even as she would become one). She is melancholic. At one point during a month-long gap in writing between June and July of 1907, printed in her meticulous script on an otherwise blank page is the following: “I have for some time lost the desire to write in here.” She is impatient with illness, recording on April 1 of that year, simply, “In bed again. Dumb!” The fact of her female adolescence is ever present in these diaries. In 1908 there is a description of a costume ball she attended, for which she reports to have dressed in a rococo style complete with powdered hair. A list of boys who gave her flowers follows, as well as a report on the costumes of others. Her dance card is pasted in, entirely full. The only dance without a signature beside it is “Ladies’ Choice.” She does not divulge whom she chose.

In 1914, the entries turn to the reality of war. A folded receipt for a five Kroner donation—“for the families of the Austrian war”—is accompanied by a handwritten note by the now twenty-year-old Lucia: “How lovely that I can donate something from money I have earned myself!” That money she earned presumably from working in the law offices of her father in Prague, but early in the war she moved to Germany, where she was a theater critic at a newspaper in Wiesbaden. Though she only stayed in that town a short time before moving to Leipzig, she remained in Germany for two decades, and it is in that country that she met László, a recent émigré from Hungary, in April of 1920. By January of 1921, they were married, on Lucia’s twenty- seventh birthday.

It has been surmised that Lucia and László married so quickly in order to secure permission for László to stay in Berlin, where he had come from Budapest via Vienna after the war. There is a photograph from the year in which they met kept in Lucia’s archive, with a handwritten note attributing the image to Berlin 1920. Lucia sits next to László on a bench with two of his Hungarian friends, everyone bundled in winter clothing. She leans over him, smiling, apparently to address the woman on his other side. László sits upright and faces forward for the camera, as do the other two people in the picture. Only Lucia appears oblivious to the fact a portrait is being taken. The woman she leans toward struggles not to laugh. László pays this mischief no mind.

Their partnership, from the beginning, seems to have been of an intense and practical nature. In Lucia’s own account of László, published in 1972 as Moholy-Nagy, Marginal Notes, she writes that “the working arrangements between Moholy-Nagy and myself were unusually close, the wealth and value of the artist’s ideas gaining momentum, as it were, from the symbiotic alliance of two diverging temperaments.” For the first few years of their marriage, she supported them financially through her work in publishing, until László earned an appointment at the Bauhaus in 1923. Together they experimented with making photograms (including a double self-portrait), but it was Lucia who developed László’s prints in the darkroom. She helped him to compose his essays from this period—“I was, over a number of years, responsible for the wording and editing of the texts that appeared in books, essays, articles, reviews and manifestos,” she writes—that are arguably as integral to his legacy today as his paintings or photographs. Lucia describes her dismay years later to see a note of thanks László dedicated to her at the front of one book edited out of a later edition and praise for the “unparalleled conciseness and lucidity” in the prose of his most famous book, Painting, Photography, Film directed at László alone. “All those years we had kept quiet about the extent and manner of our collaboration,” Lucia writes. “How should friends and colleagues have realized the exact circumstances?”

In fact, it would not have been that hard to realize. László, Hungarian-born, had not entirely mastered the German language, whereas, Lucia, having grown up in the German-speaking enclave of Prague, was well equipped in several languages. Edith Tschichold—wife of Jan Tschichold, who authored the 1928 graphic design manual The New Typography—writes explicitly in a letter from 1982 of Lucia’s invaluable linguistic assistance to her husband. Edith writes, “It’s about time your important contribution to the history of photography has finally been shown, and that for once it has been said that you edited all of Moholy’s books and articles, and re-wrote them in proper German. When one heard Moholy speak, it was of course somehow very charming, but speech and the written word are two different things indeed.”

In an introduction to a book of Lucia’s photographs published in German, Rolf Sachsse describes how she “not only guaranteed the practical execution of his work, but also the theoretical formulation of his ideas.” Such a comment figures Lucia more as László’s ghostwriter than a copy editor or dutiful wife typing up her husband’s manuscripts: the woman who was able to articulate his thoughts and craft them into the treatise with which only he is now associated. In her lifetime, and also since, Lucia has rarely received due credit as collaborator on László’s photographic prints and famous essays written during their years together at the Bauhaus.

Walter Gropius had founded the school in Weimar in 1919, with the goal to “bring together all creative effort into one whole, to reunify all the disciplines of practical art.” He envisioned an environment where “friendly relations between masters and students outside of work” are encouraged by means of “plays, lectures, poetry, music, fancy-dress parties.” Walter made manifest this vision for an all-immersive school when he began work on the Bauhaus buildings in Dessau, then a burgeoning industrial town that became the school’s campus, today a sleepy post-Communist destination for tourists less than two hours’ train journey from Berlin. László and Lucia followed to the new campus, where they came to live in one of the Meisterhäuser, or Masters’ Houses.

Lucia did not like living in Dessau. I know that by leafing through her diary from the period, this one bound in a cloth of printed vines and circular, abstract flowers. In an entry from 1927, she writes (in the Bauhaus convention of all lower case), “dessau is like a place in which someone—travelling—misses their connection and has to wait for the next train. nothing more than a place to wait for the next train. one would do better to never get off in this city in the first place.”

I have visited the town of Dessau and the building in which the pair lived. At the time of my visit, I had already read Lucia’s diaries, and so I knew she did not care for this sleepy place. I stood on the lawn in front of her house and looked across the street, imagining what she might have seen when she looked out the front windows of her home. It was a sunny spring day and the trees and grass around the house shone a cheerful green. But in one of her own photos of the house, it stands cast in shadow, the stark white of its geometric exterior rendered in gray. In another image she took of the houses together, a view to the buildings is interrupted by a row of tall trees in front of them, black and tightly clustered like jail cell bars.

In the Bauhaus archive, there is a series of images categorized under the heading “Leben am Bauhaus” [“Life at the Bauhaus”]. In one of these photographs, dated to 1926, the year that Lucia and László were able to move into their own Master House, the couple takes a break during a jaunt in the countryside to pose with their bicycles. It is a sunny day and the figures cast long shadows. László beams and waves at the camera. He is sandwiched between Marcel Breuer (who directed the furniture workshop) and his wife Martha Erps. At some distance from this tight cluster, Lucia holds up her bike with one hand, clutching her other arm across her body. She smiles unconvincingly. The front half of her bicycle is already outside the frame of the photo, as if she were eager to quit with the staged revelry and get on with it.

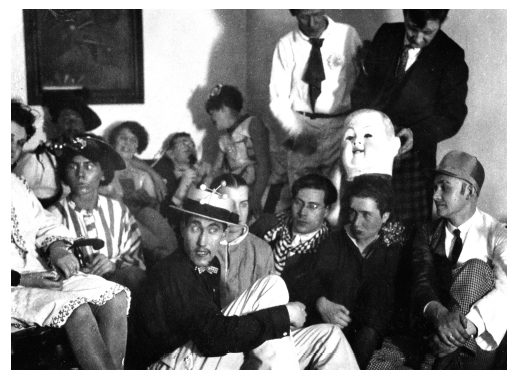

In another “Life at the Bauhaus” photograph, a number of major figures at the school convene for a party at what is thought to be the Master House of Wassily Kandinsky. While partygoers in the background laugh gaily, guests in the foreground all look rather disconcertedly at something outside the photograph’s frame. Lucia has an inscrutable expression on her face—her piercing eyes and puckered lips somehow give off the incongruous impression of an angry glare that attempts to restrain a smile. Again, she holds the limbs of her body close to herself; her knees are pulled to her chest as she is seated on the ground next to László, who leans in toward her but does not touch.

The photograph from the Kandinsky party offers compelling motivation for Lucia’s general appearance of guardedness in the “Life at the Bauhaus” images: even as she clings to herself, some unnamed male carouser behind her is caught in the moment just before he slides the huge and leering costume head of a baby over her own. Lucia’s face is heavily made up. She is wearing a blouse or dress with a giant poofy thing on the left shoulder that makes her look as though she were wrapped up as a present with a bow on top. It is painful to look at this great artist memorialized in such a way, as a woman all dolled up and unaware, with little control over what is done to her.

It is entirely unsurprising then that she describes in her diaries her alienation in Dessau and a hunger for a different milieu: “i need something that i am not finding here . . . other people and a different circle around me. it just doesn’t suit me, when every week 20 new friends come. here they are our captives and bring nothing but their organs, which they want stuffed full. i must leave from here, where others share their strengths and now and again warm up to me as well.”

Unlike the overflowing diaries of her adolescence, Lucia’s diary from Dessau is sparsely populated with mostly brief jottings. Also unlike the earlier journals, this one requires no key to open, but Lucia rendered some of it impenetrable by different (and ultimately more effective) means: many entries are inscribed in a stenographic script. She has anticipated the unwanted interloper this time, and put up a barrier between her written self and the other. Considering the legible contents of this diary, in which she complains of her time at the Bauhaus in Dessau and László’s inability to sympathize, it is likely that it is precisely with her husband in mind that she occasionally employed an inscrutable script. And yet, where the words can be read she often addresses him explicitly, as though she were only able to say to herself what she hoped he could know.

It is clear from Lucia’s diaries that she does not count on László to sympathize with the estrangement she feels in Dessau. In May 1927, two years after they moved from the original Bauhaus location in Weimar, Lucia writes: “dear laci—why can you not believe me, that it is the big city that suits me? [. . .] i simply can’t bear it anymore, even though i’ve traveled some in this time [. . .] it’s not the same thing as how one just needs a bit of meat every now and again because he doesn’t only want to eat spinach every day. believe me—i need a change of environment. the goal is not for me to leave you, but rather to find you again.”

In the end, she did not leave László before they left Dessau together. And there are hints of what was good in her time spent there. Again in her diary, she writes: “dear laci—you have so much more strength than I do. [. . .] were i as vivacious as you, it wouldn’t all be so necessary. but i can’t manage it, the beautiful part of things here only makes it all the more clear—all the more clear to me, what I could lose.” What Lucia found beautiful in Dessau, what she feared to lose, can be glimpsed in the now iconic photographs that she took of the school and its faculty and student body, photographs, as Robin Schuldenfrei writes, that have since “played an inestimable role in the construction of the Bauhaus’s legacy.” Lucia’s portraits of commercial objects created at the school—Marcel Breuer’s chairs and Marianne Brandt’s teakettles, for instance—are eerily lifelike, despite their austere geometry and reflective metal surfaces. And it is in her portraits of women at the Bauhaus, of Ise Gropius, Anni Albers, or Florence Henri, that we get a rare glimpse of the indelible presence of women there.

Of course, Lucia also took pictures of László. Many of these are almost inextricably associated with his name; they are on postcards and book covers, in catalogues of his work. In one of the most famous images, he wears work overalls and stands in front of a geometric background of whites and blacks. Frederic Schwartz describes László as “play[ing] the part of the technician in a mechanic’s overalls.” (Schuldenfrei reports that they were in fact a “fisherman’s coverall;” they were not then a workaday blue, but rather, as Schwartz puts it, a “bespoke, bright orange.”) A tie and dress shirt are revealed underneath by the unbuttoned, open collar of the overalls, as though he were ready to strip at moment’s notice from “technician” to “master,” the Bauhaus version of Superman.

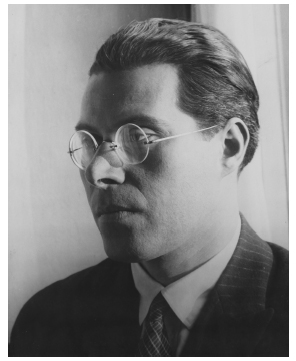

In one headshot, László is without the overalls, dressed professorially in suit coat and tie. In his round, rimless glasses, he is seated at a three-quarter angle to the camera and stares straight ahead, the right side of his face cast in shadow. His hair is slicked back. His expression is stern. In the archive, the photo is attributed to Lucia, but with the following parenthetical disclaimer: “(In the opinion of Hattula M.-N. not by Lucia M. Letter from 10.21.94).”

Hattula is László’s daughter, by his second wife, Sibyl. A copy of an e-mail she sent on February 21, 2011, is kept in a file with photographs of László at the Bauhaus-Archiv, and states in red: “These shots of Moholy are almost invariably attributed to Lucia Moholy, even the photo of 1919 [of László standing by what she believes to be the Chain Bridge in Budapest] before they even met. But, because they were all made with his own camera and not hers, we cannot say with certainty who actually took these photographs, so I consider them to be self-portraits until we have further information.”

This relatively recent e-mail appears to have been sent in response to an inquiry into the negative of “the photograph of Moholy at the easel—most likely in Weimar.” In the image to which I believe this negative corresponds, László is definitively in the role of the artist, the “mechanic’s overalls” turned painter’s smock. If Hattula wishes to suggest that this is one of the photographs inaccurately attributed to Lucia, it is very hard to imagine this shot could have been staged by the artist himself, caught as he is immersed in the act of painting. The geometry of the composition has the signature stamp of Lucia: the square grid of glass panes of the ceiling skylight above him and the legs of the easel at which he stands, as well as the black lines on a white wall in the photograph’s background, are all reminiscent of Lucia’s work from the Bauhaus years. The argument that the photographs were taken with his camera as a way to remove authorship from Lucia feels particularly flimsy. Lucia and László were a married couple, after all, and surely shared much more than a camera.

The question of who took the photographs, however, is of course worth seriously considering—it is a reminder not to take for granted what we assume to know. I believe that Lucia did take those photographs, and to question that chips away at what little authorship a formidable artist has been given. But at the same time, we simply do not know for certain. To question her authorship of those photographs speaks to a more general problem when writing history: there is always the risk of revisionism, of reading ambiguity in a way that furthers a narrative we wish to construct. It serves my purpose to assume Lucia took those photographs, as it serves Hattula’s to assume she did not.

There is also, of course, a danger in acknowledging this. It is all too easy to re-appropriate agency toward the ones who already hold claim to most of it. And indeed, in the years after the Bauhaus closed and Lucia left Berlin, her negatives were distributed and used for reproduction without proper attribution or consent, or even her knowledge that they continued to exist. The result has been a persistent uncertainty over what images are hers; testament to this is that of the photographs reproduced here, several are attributed to a photographer “unknown” or Lucia or László with question marks behind their names. And yet, copyright permission to use these images (with the exception of the group photo) was obtained under Lucia Moholy’s name.

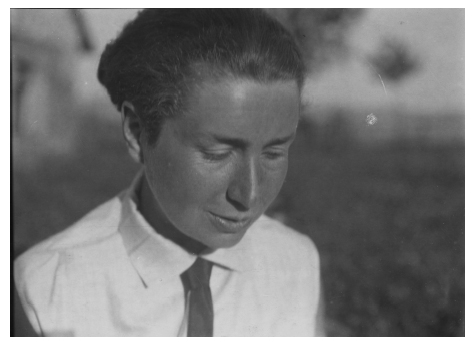

The question of ownership is extended even to the photos of Lucia herself, some of which are assumed to be self-portraits but are also tentatively attributed to László, or again, to some unknown other. In these images, we see that Lucia also dressed in the manner of practitioner, in smock or suit, subverting notions of standard female dress in the process. In striking contrast to her costume at the Kandinsky house, she typically wears little to no make-up and clothing more representative of her status as a modern female artist of the interwar period. In one such photo, she wears a white button-down shirt with a stiff collar and no sleeves. The presence of a dark tie is a nod at formality and masculinity in juxtaposition to the sleeveless cut of the shirt. Her hair is pulled back away from her face. This image is undated and is possibly from her time at the Bauhaus, but comparing it with a series of similar photographs dated to later years, I’d conjecture it was taken after her years in Dessau were through.

In 1928, when Walter stepped down as director of the Bauhaus, Lucia and László left the school as well, and they finally were able to get on that next train out of Dessau, headed back to Berlin. That year, there is a three-word entry in Lucia’s diary that marks the beginning of this new era for her and the Bauhaus in general: “anfang mai: berlin” [“beginning of may: berlin”]. But the return to Berlin did not much help her relationship with László. A year later, they separated, and in 1934, officially divorced.

Within the period between separation and divorce—the years 1930 through 1932—a number of photographs of Lucia highlight a brief window of liberation. Post-Dessau and before being forced to flee the country, she smiles radiantly, eyes looking upward, in a white button-down shirt, black vest, and striped tie. In another, a close up of her head as she lies down, her curly hair is let loose, splayed all around her.

And then, there are a series of nude portraits. These images of herself point poignantly to the tragic loss of agency that came with the loss of Lucia’s negatives: all are attributed to a photographer “unknown,” or to her, but with that question mark behind her own name. On the back of each photograph, in what appears to be Lucia’s own hand, she writes her name in pen. Later, in pencil, an archivist has added, “no negative.”

One series of portraits were taken outside, on scraggly rocks with brush in the background. Lucia lifts her arms and legs at various angles to the camera, making constructions with her body. We see her from the side, from behind, and facing forward unabashed, right hand cupped over her eyes to shade them from the sun as she peers off at something in the distance beyond the camera I believe she set up herself. In nature, she is uninhibited, seeming to delight in her naked body touching against the open air, no human soul in sight. She looks like an awkward bird, set free, about to take off in flight.

Another set of nudes are taken in a bedroom. There is something about these, too, that suggest she is both photographer and subject. The way that she looks into the camera, the posture she takes on the bed, is at once so wholly intimate, and without an object of intimacy at which to direct her stare. In one of these photos, her gaze is a vast blank, pupils nearly all white. The geometry of her Bauhaus photos is also present here: in one image that recalls her famous portrait of Moholy (minus the overalls), she stands with her back to the camera, face in profile, against solid blocks of blacks and whites.

In these photographs she is beautiful and she is alone. Perhaps in laying her whole body bare on film Lucia offers permission to be looked at, dares the viewer to see her even. And yet in the archive I can’t but feel once again that I am the voyeur she never envisioned, leafing through her life with white-gloved hands.

Two years after Lucia and László left, the Bauhaus was forced to quit operations in Dessau entirely and move to Berlin due to National Socialist pressure. There, the school lasted only three more years, until 1933. That same year, Lucia fled Berlin herself, leaving approximately six hundred negatives behind, and ultimately ended up in London (via Prague, Vienna, and Paris) the following spring. László arrived there a year later with his new wife, apparently leaving Lucia’s negatives in Berlin in the care of Walter. László with Sibyl then immigrated to the United States in 1937 and set to work establishing the New Bauhaus in Chicago. In the same year, Walter and his wife, Ise, moved to Cambridge and had Lucia’s negatives sent over with the rest of their things, which Walter then used to build the legacy of the Bauhaus abroad, though he only admitted that to Lucia nearly two decades later. As Schuldenfrei writes, “The uneven power equation between Gropius [. . .] and Moholy, with little wherewithal in London and rendered virtually anonymous by her [missing] negatives, was one that both were distinctly aware of.”

Left in London, Lucia depended on her old colleagues to help her obtain her own passage to America. After a rocky start, the New Bauhaus dissolved, and reopened as the School of Design (which is now a part of the Illinois Institute of Design). Through his position there, László was able to offer Lucia a post as a teacher of photography with a salary of two hundred dollars per month, to start September 1940, in order to facilitate her own application for immigration. In a letter he wrote to the American Consulate General on her behalf, he writes explicitly for perhaps the only time of the important contributions of Lucia at the Bauhaus: “Lucia Moholy-Nagy was one of the former collaborators at the Bauhaus and was, with her scientific, practical and human qualities, one of the most valuable members of this community.” He forwarded a copy of the letter to Lucia, and added the slightest hint of their former intimacy in his personal comments to her (mediated as they are through the “we” of he and Sibyl): “We think with horror about European events and you are daily in our thoughts with all of our friends in London.” But in the most subtle nod at their former status here, the sentence is made doubly sad, addressing as it does not only the uncertainty of Lucia’s future, but also the total breakdown of their relationship. As salt to the wound, he signs off as though addressing a business partner: “Yours very sincerely, L. Moholy-Nagy.”

In addition to the prospect of employment, Lucia also had the support of her brother Franz, who had already been living in the United States for six years and who completed an affidavit in support of her immigration application. He testifies to working as a writer in Beverly Hills with a stated weekly income of $250, $18,000 in the bank, and $9,000 in property value. And yet, despite submitting “very complete documentation,” Lucia’s application “to obtain a nonquota visa as a professor within the meaning of the immigration laws,” was denied by the American Consulate on December 2, 1940, with the explanation:

I regret to have to point out that it appears that your principal vocation for the past six years has been that of professional photographer and writer. It further appears that your teaching experience was confined to a two-year period, 1930–1931, when you reportedly taught in a school in Zurich. Under the circumstances, it is not felt that it could be considered that your principal occupation was that of professor within the above-cited immigration law.

Your name has nevertheless been added to the list of applicants who are awaiting their turns under the Czechoslovak quota, and as soon as your turn is reached, you will be notified.

So it is a cruel irony that without her negatives, Lucia was forced to establish her photography career in London with no portfolio, and at the same time was not successful in her US visa application because during the Bauhaus years she had worked as a photographer and not a teacher. A series of terse letters between Lucia and László followed this rejection, with him always maintaining the tone of potential employer. On New Year’s Eve 1940 Lucia attempted to solicit some response to the bad news for a third time: “The last I wrote to you was my letter of December 12 and my telegram of December 13 which ran: ‘Consulate refuses non-quota lacking professional experience last years stop Can you approach State Department Love Thanks.’ I wonder what you felt about it? I have been anxiously waiting for a reply.”

On January 15, 1941, she received little more than the following from László: “We are trying to find some solution for your problems but apparently it is a very difficult matter,” with the promise that Sibyl would follow up with a longer letter (which she does). By March of that year, as the struggle continued, it appeared that László wanted to extricate himself entirely from any responsibility of securing the visa: “We have heard with great regret that the difficulty of booking a passage has prevented you up till now from fulfilling your contract with the School. We appreciate of course the great complications which have arisen from the general situation, but we want to tell you that we did count very definitely upon your work during our coming summer and fall sessions. [. . .] Your failure to arrive would bring us into a rather disagreeable situation.”

A few more depressing letters followed, but ultimately nothing came of Lucia’s repeated attempts to secure passage across the Atlantic. And then, the war ended. And then, László died.

Still in London in 1946, Lucia received a telegram with the news from Sibyl on the day of his death:

=LACI DIED NOVEMBER TWENTYFOURTH WILL WRITE SOON LOVE

=SIBY.

The news came as a shock to Lucia, who always expressed affection towards László, even though they had struggled to live happily together. After his death, relations between Sibyl and Lucia became increasingly strained, in particular around repeated inquiries by Lucia into the whereabouts of her negatives. Ultimately, she enlisted the help of a lawyer to help track them down, from Walter on the one hand and Sibyl on the other. In 1957, Lucia did receive a crate of them from Walter, shipped to her in London at her own expense. In 1959, she moved to Switzerland. She never did immigrate to the United States.

One of my favorite photographs of Lucia captures her in a happier moment, taken before the trials of her failed US immigration, László’s subsequent death, and her struggles to track down years of past work. In this one, she is seated at the edge of still water, leaning back and at ease. Her arms are spread wide and open along a wooden railing. She looks at the camera with a full smile and partially squinted eyes. Her wavy hair is pulled back and she wears a full-length, sleeveless white dress with a belted high waist. She is all light against the dark of the water’s surface behind her.

There is no date on the back of this photograph, but it is hard to imagine it was taken before 1930 or after 1933. She is captured in a moment of freedom, her limbs wide open. With the water as her backdrop, she can finally let herself be vulnerable. There is no one behind her to try to cover up her face.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

All cited correspondence, as well as Lucia Moholy’s diaries, are held at the Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin. (Diaries and some correspondence originally in German.) Special thanks to Wencke Clausnitzer-Paschold, Sabine Hartmann, and Randy Kaufman.

- Gay, Roxane. Bad Feminist. New York: Harper Perennial, 2014.

- Gropius, Walter. “Programme of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar” (1919) in Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-Century Architecture. Ed. Ulrich Conrads. Trans. Michael Bullock. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1970.

- Moholy, Lucia. Marginalien zu Moholy-Nagy/Moholy-Nagy, Marginal Notes. Krefeld: Scherpe Verlag, 1972.

- Sachsse, Rolf. Lucia Moholy Bauhaus Fotografin. Berlin: Bauhaus-Archiv, 1995.

- Schuldenfrei, Robin. “Images in Exile: Lucia Moholy’s Bauhaus Negatives and the Construction of the Bauhaus.” In History of Photography 37:2 (May 2013): 182–203.

- Schwartz, Frederic J. “The Eye of the Expert: Walter Benjamin and the Avant Garde.” Art History 24:3 (2001): 401–444.