This Way to the Führerbunker: Gertrud-Kolmar-Straße, Berlin, Mitte

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The visitor to twenty-first-century Berlin finds it hard it to accuse the government of a reunified Germany of failing to acknowledge the horrors of the National Socialist era. The block on Prinz Albrechtstraße once housing the police apparatus of the RHSA, SS, SD, and Gestapo has been leveled to its subterranean core and now holds a comprehensive exhibition on the Nazi crimes entitled the Topography of Terror. Several blocks north along the Wilhelmstraße, once the axis of the old Hitler ministries, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, a vast, undulating, horizontal field of unmarked stelae, features an underground information complex fully documenting the Nazi death apparatus across the occupied lands. The suburban Wannsee villa where plans were adopted for the Final Solution has now become a permanent historical center. The Jüdisches Museum Berlin details the once vibrant culture and eventual fate of Germany’s Jewish community. The Bendlerblock, former Reserve Army staff headquarters, where several of the 20 July 1944 conspirators, including Count Klaus Schenck von Stauffenberg, were executed in the courtyard, now houses a memorial museum to the German Resistance.

Not without reason—given the continued existence of neo-Nazi organizations in Germany and elsewhere—one other location of substantial notoriety is less noted on maps and in guidebooks. It is the site of the bunker where Adolf Hitler committed suicide on 3 May 1945 and where, just outside the chancellery garden entrance, an attempt was made to burn his body along with that of his wife, Eva Braun. Once a barren expanse of rubble just beyond the Berlin Wall in the Communist zone, it is now a parking lot, used by tenants of a cluster of surrounding high-rise apartments built in the mid- to late 1980s by the former East Germany, presumably for party elites. Erected nearby is a panel giving historical information and including a detailed diagram of what turns out to have been an extensive set of underground fortifications built for various ministries and official residences. Taking the diagram at ground level as an overlay of the present terrain, one finds it possible to place with fair precision various final scenes in the shabby Hitlerian Götterdämmerung: the small parade ground where a visibly decrepit Führer is shown in a famous photograph giving a boy hero of the Volkssturm a fatherly pinch on the cheek, the rubble-strewn dooryard where another shows him allegedly taking his last mortal glimpse of the outside world, the nearby shell crater where the Russians discovered the decomposing, partially incinerated bodies of the newly married Herr and Frau Hitler. Along with a piece of skull and some dental bridgework in a Moscow forensic lab and some leftover ash and bone scattered under an old Soviet truck park in Magdeburg, this patch of asphalt and concrete in Berlin is as much of Hitler’s tomb as we will have. Though no one can say how the historical marker came to be there, it is acknowledged to be of private installation. It is said residents of the housing complex are extremely desirous that it be removed.

For a historical person such as me, an American born in the waning days of World War II, it remains a place of dreadful fascination. Now in my late sixties, I have grown up on images of good-guy Americans fighting Hollywood-movie Nazis and brave, freedom-loving, postwar West Germans striving against their totalitarian East German Communist counterparts. In my young adulthood, I myself served my nation in combat as a military officer in Vietnam, a war of dubious moral and political legality frequently described as genocidal; in my later life and career I have written a great deal about war and its cultural representations, of the degree to which leaders devise military myth to clothe their designs of aggression with false vestments of just ideological or geopolitical purpose—and not least of the degree to which war continues to be a vehicle of political and religious extermination. Most recently, I have witnessed my nation invade Afghanistan and Iraq—two overlapping conflicts that together constitute the longest war in American history. In Afghanistan the objectives have shifted from the post-9/11 hunt for Al Qaeda to an increasingly futile counter-guerrilla struggle against an Islamic insurgency; the conflict in Iraq, albeit resulting in the overthrow of the dictator Saddam Hussein, has been largely regarded from the outset by many observers both here and abroad as an act of unilateral aggression. It may be remembered that this is the crime for which, at Nuremberg, we hanged many of the prominent Nazis remaining alive after the German defeat.

For all these reasons and more, this is one of the main places, I have to admit, that I have come to Berlin to see. Call it a cultural or literary conceit, but it is there. To me this German parking lot, early in the twenty-first century, still represents somehow the epicenter of evil in a whole vast epoch of mass killing. Yes, I have used the word, for I can think of no other. And, yes, I know the mathematics of totalitarian murder, how one can bludgeon an audience with comparative numbers. Stalin killed more, probably twenty million, mostly his own people. The other great name frequently invoked in the horror sweepstakes is Mao Zedong. For sheer recent viciousness, we must surely honor Pol Pot and Saddam Hussein. The American War in Vietnam alone probably killed between two and four million Vietnamese. Ho Chi Minh himself is frequently accounted as having let two million starve during the 1945 Red River rice famine. Before that, in the West, the Atlantic World of slavery and concomitant extermination of native peoples claimed literally uncounted tens of millions, at best approximation ten to twelve million deaths for African slavery and possibly twenty million or more for original Americans. The Holocaust, as is well known, is usually reckoned to have taken six million lives, and World War II around sixty million. The German distinction, with a cruelty unmatched save by perhaps the Japanese in China, lies in the mass killings of largely defenseless victims, undertaken with the most calculated and purposeful malice. Of German Holocaust victims alone, one half remain nameless and forever unaccounted for, having simply vanished into the horror and the flames. This is to say that the real distinguishing feature of the Hitler regime, conferring upon the German people the notoriety of having committed the greatest crime in history, is the degree to which it committed an advanced modern nation to the belief, espoused by its supreme leader, that a certain kind of fellow person—a single individual human being or millions of such individual human beings—had no right to exist on earth: that the lives of certain human beings could be conceived of as accounting for nothing; and of the further degree that, to this end, it committed itself to the industrialized mass murder of the innocent and defenseless. This is monstrous. But it was itself done by persons—by human beings. On that account, I have somehow found it necessary to come to the place where the leading perpetrator in that crime—a real, living, person named Adolf Hitler, with whom I actually drew breath on this planet for at least six months in 1944–1945—met his own death.

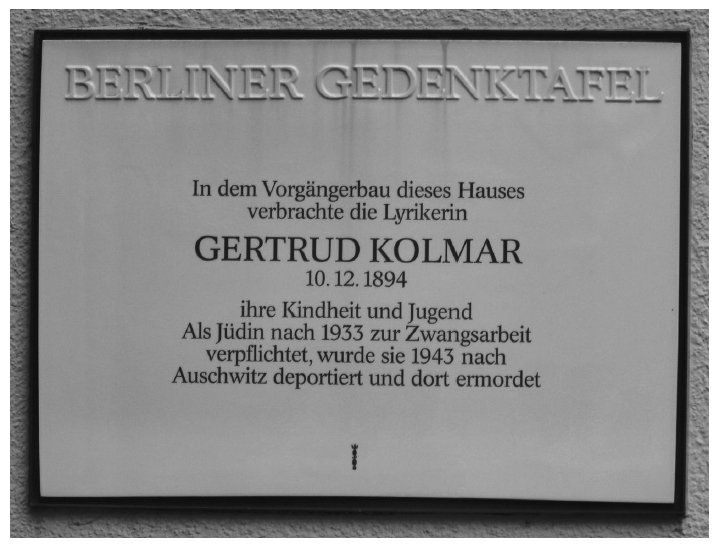

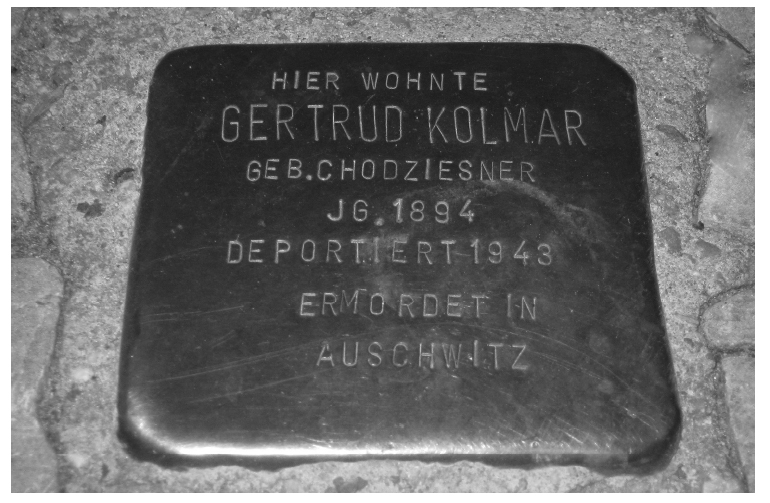

Meanwhile, at this exact place, here in the same quiet, leafy section of the part of Berlin called Mitte, within sight of the Tiergarten, the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, the Pariser Platz, the old Hotel Adlon, I find that art, history, and memory have also been intersecting to create their own strange, haunted cartographies. To be specific, this is what one finds as one now gets to the place in question by walking a short block west from the Wilhelmplatz, the site where Hitler and his minions enjoyed countless rallies, parades, and demonstrations, on a street called An dem Kolonnade; or in the alternative, by walking roughly the same distance east from the Tiergarten on an old Wilhelmine avenue of missions and embassies called In den Ministergärten. The name to remember from the map—the place where all the vectors meet—is the Gertrud-Kolmar-Straße. And so, it turns out, does this cartographic fact become an unexpected new opening to history and memory in the fullest sense. For it is just here, of all places, that one now encounters a name recalling the tale of a life almost breathtaking in its sorrowful juxtaposition of the beauty of art and the obscene ugliness of Nazi cruelty.

The twentieth-century German poet Gertrud Kolmar now merits a few entries in English-language biographical guides. The basic facts of her life history are these. She was born in 1894 in Berlin. In 1943 she was murdered at Auschwitz. Her literary remains include around 450 poems, two short novels, a few short stories, some plays, and a body of letters. As becomes vividly apparent to anyone who studies her, in the slightly less than five decades she spent on earth, Gertrud Kathe Kolmar fashioned an existence intensely and bravely her own both in life and art. Born into an assimilated middle-class German Jewish family, she grew up in Berlin’s affluent Charlottenburg quarter and was educated in a series of private schools. In the years afterward, she worked variously as a teacher, governess, interpreter (Russian, English, French) and as an assistant to her father, an eminent criminal lawyer and jurist. Her places of residence besides Berlin included Leipzig, Hamburg, Paris, and Dijon. Beginning to publish poetry, she changed her last name from Chodziesner, based on the Polish name of the town in the eastern region of Posen, where her family originated, to Kolmar, its German equivalent.

At least once she seems to have experienced intense romantic love, with a military officer by whom she became pregnant. This relationship reached an abrupt terminus when she was forced by her family to undergo an abortion. Throughout her ensuing adult life and career, she remained unmarried, with a markedly inward turn of consciousness and vision. As a Jew, she found her life from 1933 onward essentially dictated by Nazi persecutions. With her father, whom she had returned to Berlin to care for after her mother’s death, she was forced to move into a crowded apartment shared with other dispossessed Jews and was conscripted for labor in a factory doing war work. In 1942, her father was transported to Theresienstadt. Nothing further is known of him. In early 1943, Gertrud Kolmar herself was arrested in an SS factory sweep and sent to Auschwitz, where she was gassed and incinerated.

Her body of literary production between 1917, the date of her first book, entitled Gedichte, and 1943, the year of her death, turns out to have been substantial. As a poet, she produced several more increasingly accomplished volumes, often with major subsections and thematic arrangements composed in articulated cycles. A selection of the poems was published in English in 1975. The two short novels and a collection of letters are now available as well. The plays were published in German in 2005. In Germany itself, the poetry has become the major focus of reading and revival, with publication of a handsome, three-volume 2003 German edition, including notes and commentary by the late Regina Nortemann.

In some sense, then, out of the literary archive, history and memory now also write their own archaeologies. A Gertrud Kolmar rediscovery seems to have accrued the large energy of posthumous publishing and cultural recognition. Out of the silence of death, not unlike the American Emily Dickinson, or, perhaps in an equally relevant analogy, Sylvia Plath, we see the scrupulous edition and publication of the primary texts. Meanwhile, in the closer contexts of twentieth-century German literature and the visual arts, an emergent body of critical discussion may now begin to locate her in relation to the experimentalist work of contemporary Jewish women poets of the era such as Else Lasker Schuler and Nelly Sachs, as well as in her frequent imagistic voyagings onto the landscapes of modernist nightmare familiar in the work of German expressionist painters, illustrators, and sculptors, including Otto Dix, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckmann, and Käthe Kollwitz.

In all this, one would like to find at least some small redemptory message—something, perhaps, about the triumph of art over brutality and barbarism. In the present case, the word to remember is “beware.” Beware, that is, and be prepared to look down into an abyss of sorrow from which one may not find it possible to turn away. Here, amidst the mass infliction of endless terror and pain on millions, we come upon the astonishing experiential and artistic record of one such person, living fully in history: a woman, a Jew, a deeply assimilated and acculturated German, an artist-intellectual steeped in the vivid experimentalisms of German art between the wars, above all, a poet. And what one finds, on all such accounts, is a chronicle of such unspeakable sadness that it can barely be read, let alone written about.

At present, Kolmar is visible to English-language readers through a handful of her later poems—all firmly mature in experiential vision and highly ambitious and accomplished in their aesthetic virtuosity. Two of them are reproduced here and briefly discussed: “Die Dichterin” / “The Female Poet”; and “Aus dem Dunkel” / “Out of the Darkness.”

Here, in the original German at least, from the first word onward in Gertrud Kolmar we frequently encounter a studied forthrightness of address which we must take care not to lose in translation. In English, the poem’s commonly rendered title is “The Female Poet.” Given no doubt in deference to traditional gendered literary nomenclature, the precise term of linguistic and historical accuracy would probably be more like “poetess,” a word no longer used in England and America, but in the German equivalent invoking the writer’s own sharp awareness of the relationship between gender and poetic authority. In German, Dichter is “poet” or, more generally, “author,” as opposed to “writer.” “Dichterin” gives the word a female ending but remains one word. Accordingly, for Kolmar, the word itself poses the relation of authorship and authority as the first in a complex set of figures of identity—in ways highly reminiscent of her American counterpart, Emily Dickinson—through a series of what might be called literary impersonations. These begin with the opening lines. “You hold me now completely in your hands. / My heart beats like a frightened little bird’s / Against your palm.” The image is that of a fragile wild creature. Yet the translator who goes too far with the ruse, as in the parallel text given here, may be taken in. The German diminutive “eines kleinen Vogels” in the lines, one grants, means “little bird.” But the German adjective for “frightened” exists nowhere in the original. “Schlägt” can of course be translated as “beats” as in the case of a beating heart. But it can also be taken to mean “strikes” or “thuds.” There follows then the fierce admonition by the speaker, on any account, not to confuse personality with poetry. “Take heed!” she writes. “You do not think / A person lives within the page you thumb. . . . Some binding thread and glue, and thus is dumb, / And cannot touch you (though the gaze be great / That seeks you from the printed marks inside), / And is an object with an object’s fate.” The message in this figure of the autonomous text is that one must read carefully the work of a poet one presumes to hold in the palm of one’s hand. Who holds this book, she seems to say in echo of Walt Whitman, holds a person.

The poem now shifts tones again, becoming from this point onward vividly erotic. The text is openly female, “veiled like a bride, / Adorned with gems, made ready to be loved, / Who asks you bashfully to change your mind, / To wake yourself, and feel, and to be moved.” Here, in luxuriant echo of the ancient Hebrew songs, the poem becomes a seduction, a text of a woman alluringly begarbed, bejeweled, desirous of the great moment of union. Yet in a final turn, this figure too yields to a hard understanding of the likely resistances that await the speaker as both a woman and a poet. At the end, she seems to tremble not so much in the idea of consummation itself as in the knowledge that any such moment is always, at least in a woman’s world of “you” or “you and I,” never fully to be. Men, she has admitted earlier, half in flattery, half in rue, are always “cleverer” in their own world of “truth and lie.” In such a world, “This book,” she goes on, for all its adornments, “is but a girl’s dress in rhyme, / Which can be rich and red, or poor and pale, / Which may be wrinkled, but with gentle hands, / And only may be torn by loving nails.” She concludes: “I call then with a thin, ethereal cry. / You hear me speak. But do you hear me feel?” The forlorn figure, at once the woman and the poet, stands alone at the end, with one last appeal to relationship registered in a cry of pain and separation.

As a complex work of evolving identity and voice, “Die Dichterin” thus reveals itself as the achievement of a poetics born from the woman’s deepest resources of experience, an erotics of writing in the fullest sense. Indeed, as noted by Kolmar’s English translator, Henry A. Smith, throughout her work, there is “an unprecedented frankness and intensity in her portrayal of female sexuality,” coming close at times, in the phrasing of the poet Karl Krolow, to a kind of “maenadic madness.” Yet here, as so often in Kolmar’s poetry, her attempt to move the struggle for personhood beyond desire toward full relationship, becomes at the end agonizingly foreclosed by the male signifier. Again, the English, even in respectful translation, cannot do it justice. In the latter’s emphasis on the reiterated “you” and “you and I,” the final lines wind up sounding new-age sentimental, a kind of proto-pop feminist “men are from Mars, women are from Venus.” The German grammar is far more complex and suggestive in its sexual politics, particularly at the conclusion, given above as “You hear me speak. / But do you hear me feel?” The German original reads instead,“Du hörst, was spricht. / Vernimmst du auch, was fühlt.“ “You hear what is said,” concludes the poet. “But do you comprehend what is felt.” The agency of the German syntax is transferred to the male “you.” The speaker is reduced to the operation of the grammatically reflexive verbs—“is spoken”; “is felt.” “Die Dichterin” is a poem that begins and ends with the poignant crossing of idiom both deeply personal and, in the fullest sense, political.

The second selection here, “Aus dem Dunkel” / ”Out of the Darkness,” may be seen as a similar attempt to transmute an almost unbearable intensity of felt experience into forms of personal and cultural statement. Again, the central figure is the woman, the Jew, the poet, a figure of female desire cruelly estranged from the private domain of domestic life; meanwhile, in her larger vision of the social world, as with her counterparts in fiction, drama, and the visual arts, she now becomes simultaneously the solitary, outcast wanderer afoot in a world of history increasingly surreal, hallucinatory, phantasmagoric.

Indeed, “Aus dem Dunkel” may be said to reveal the further poetic extension of Kolmar’s deeply personalized figures of women’s experience into those of a fully achieved modernist masterwork—recently the subject, it turns out, of a cantata for chamber orchestra and voices by English composer Patrick Marshall. Here the poem dates from 1937, appearing as part of a cycle entitled “Welten / Worlds,” within a final 1938 book, Die Frau und die Tiere, / The Woman and the Beasts—itself, as if in grim prediction of the author’s fate, with all copies of the text summarily destroyed upon issue as the production of a Jewish author by a Jewish publishing house. In it we see the poet notably abandoning conventional poetic diction, rhyme, meter, and stanza form. Apace, we follow yet another bold yet dark journey of a woman through the world, beginning in personal figures of desire and loss and concluding in dark, claustral images of isolation, fearful wandering, omnipresent menace, and final entombment.

As is often the case in Kolmar’s works, the poet begins with a complex image of woman in conflicted relation to motherhood—in this case at once in the “unachieved” image that often so forcefully inhabits the poems, but here also physically embodied. “Out of darkness I come,” she writes, “a woman.” “I carry a child,” she goes on, “and have forgotten whose it is.” The expression is notably ambiguous. A pregnant woman is said to carry a child, in this case possibly illegitimate. A mother wandering through the world carries her child. Whatever the questions of paternity or maternity—licit or illicit—the role of woman’s sexuality here again defines her outcast state. The world she wanders is that of the homeless, the haunted, the hunted. The poem has become a living prophecy of the destruction that will be wrought by the war. The poet becomes the refugee, the displaced person, the faceless seeker after the final refuge or release that perhaps only death may bring.

“Unreal city,” said Eliot. So, writes Kolmar of the figure of woman in the poem, who is now completely and fully the poet afoot on the landscape of modernist nightmare. “I crossed the empty marketplace. / Leaves swam in puddles where the moon was shining. / Emaciated, greedy dogs sniffed garbage on the stones. / Fruits rotted squashed; / An old man dressed in rags still bowed his poor, tormented strings / And raised his thin, discordant, mournful voice / Unheard.

Now the eyelike windows of the unapproachable centers of power look out on the void: “Before the palace of the mighty I stood still, / And when I trod upon the lowest step / The flesh-red porphyry burst cracking underneath my sole.—”

Kolmar’s vision has become the very image of the Waste-Land. As with Eliot and his own focal figure, the blind prophet Tiresias, she writes, “Now, far away, the river whispers to its banks. // And now I stumble forward on the stony, stubborn path. / Jumbled rocks and thistles wound my groping hands.” And there, at the end, materializes the destination she has somehow known will be hers all along. “A cave awaits,” she says, and “inside its deepest crack the bronze-green, nameless raven.” She enters, she says, and drowses, attending “to the silent, growing word my child speaks.” At the end, she finds sleep, “my brow turned eastward, / Until sunrise.” We can no longer be sure about any of this. The cave has become a dim, barren womb of earth. The oracle has become the garish bird of night. The child may be a ghost presence, an imagining, perhaps even a delusion. So the dawn may be a false dawn, or just another dawn, or no dawn at all. Again, the conclusion, in the German original, seems to make such multiple suggestions. The last line reads “Bis Sonnenaufgang”—“Until sunrise,” as the translator has it. An alternative translation, with signature Kolmar directness, might read “Toward the sunrise.” The sun may make its rising; but for the poet, the sleep may be at last the silent sleep of the eternal tomb.

Here one may speak of Kolmar’s fully realized genius in transmuting personal pain into a fully rendered vision of the modernist apocalypse. Even down to the German title, as before, the voice is that of a poet most suggestive precisely in her disconcerting plainness and immediacy. “Aus dem Dunkeln,” the title reads. “Out of the Dark.” Not, as the translator would have it, “Out of the Darkness.” That would be Dunkelheit. Out of the Dark: the concreteness of the phrasing is the key. Darkness is a mood, a condition. Dark is a thing, a permanence. To the end Kolmar was willing to look the thing itself in the eye. And she did so in poems like this numbering in the hundreds—love poems, death poems, nature poems, animal poems, historical poems, an entire cycle of seventy-five alone entitled Weibliches Bildnis / Image of Woman—not to mention the novels and short stories, the plays, the letters, a few of the last, it should be noted, heartbreakingly addressed to her cousin, the writer Walter Benjamin, himself in the last stages of being hunted down abroad by the Nazis, hounded into suicide.

With texts as with people, we frequently do history by the numbers. According to the numbers, in English alone there exist more than forty biographies of Adolf Hitler. According to the Times Literary Supplement, in the last publishing year there appeared nearly four hundred titles on one aspect or another of the Nazi era. There exist no full-length life histories of Gertrud Kolmar. What do exist, of course, fortunately for us, beyond the mere two examples given above, are the texts—with hundreds upon hundreds of others every bit as rich and arresting in their strange beauty of sorrow and loss. They are the record of a poetic life fully lived, a body of work in the fullest sense, in which a human person speaks with an utter intensity of the whole felt multitudinousness of experience. At the end, this fullness of being even seemed to include the calm embrace of her impending arrest and murder. A final letter is almost unbearable in its quiet bravery. “So I will step beneath my fate,” she wrote, “be it high as a tower, be it black and oppressive as a cloud. Even though I do not know what it will be: I have accepted it in advance, I have given myself up to it, and know that it will not crush me, will not find me too small. . . . And I will bear it without complaining and somehow find that it belongs to me and that I was born and have grown to endure it and somehow to outlive it.”

How could this happen, one asks, echoing the question that so many have asked now so often over so many years. How could it be that an allegedly civilized people—the people of Bach, Schiller, Goethe, and Beethoven—could do the things they did to such a person as Gertrud Kolmar, and then add to that all the other millions, so many of them possessed, if not with her gift of poetry, at least with an equal avidity for experience, a capacity for love, at the end perhaps a wondrous, transforming dignity?

Here, for me at least, the writing just makes it worse, the record of this life that counted for so much in the world. Where was she the day they came to get her for the last time? The factory where she was a slave laborer? The filthy, crowded, noisome flat in the Jewish holding block housing from which they had already taken her father to Theresienstadt? The roundup squad—were they Gestapo, SS, SD, Kripos, some kind of officious little auxiliaries in their snazzy little uniforms? Where was she herded aboard the train? The Grünewald? The Anhalter? In the boxcars, was it cold that early spring? Was she hungry? On the platform at Auschwitz, was she part of the selections, labor to the left, immediate execution to the right? What were the last moments like for this beautiful woman, this poet, this so completely vibrant and aware person, in the chambers, amidst all the naked, jostling, panicked, screaming. What went up the chimney that day at the crematoria? A human person, a woman, a Jew, a poet, named Gertrud Kolmar.

As with W. G. Sebald in his great novel Austerlitz, one looks vainly for a single redemptory feature here of history or memory and finds only the unbearable sadness of names—of the odd individual, solitary, obscure, doomed, amidst all the millions of the relentlessly terrorized and murdered. To be sure, one honors the manifest courage of Gertrud Kolmar’s human resoluteness in the face of annihilation. And so, in tracing the long passage toward death of one such human individual, one life out of the millions and tens of millions, one may at least speculate, as posited by recent historians such as Richard Overy, Andrew Ward, and others, that the Nazi regime finally reaped the reward of the utter human smallness and cruelty that repeatedly channeled their thoughts and energies—to the diversion of attention from the desperate military war effort—into manic score-keeping and account settling with already helpless individuals and target populations: the millions in the occupied territories, the Jews, the Slavs, the Gypsies; Eastern Europeans, Poles, Czechs, Russians, Ukrainians; intellectuals, clergy, educators, members of the professional classes; in Western Europe, the Jews of the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, France. As late as 1945, with German armies collapsing everywhere, immense effort was devoted to the Jews of Hungary. And then there was the madness at the end, the attempts to march the prisoners into the Reich, on the bizarre notion that it might be possible to destroy evidence of the existence of the camps.

Or, on a larger strategic note, one might adduce as just reward for obsessive Jew-hatred from the first years forward of the Nazi regime—again fatally compromising the war effort from start to finish—the truly idiotic persecution of Europe’s most brilliant mathematic, scientific, and engineering minds, nearly all of whom chose exile, and eventual work for the allies in nuclear physics. As with their cohorts in “degenerate art,” removed from their jobs and hounded out of Germany in the thirties under the bizarre concept of “Jewish science,” it was they—the theoretical physicists and engineers beginning with Einstein and including Otto Frisch, Leo Szilard, and others—who made certain that their persecutors did not arrive first at the nuclear technology that in their hands might have put the entire globe in thrall for a new dark age.

Likewise, in a multitude of instances, one finds a diversion of enormous energies away from the German war effort and into bizarre preoccupation with particular political individuals. There is the case of Georg Elser, a solitary, humble Swabian workman who had barely missed assassinating Hitler with a bomb during the annual Bürgerbräukeller commemoration in Munich in 1939 and kept alive as a “special prisoner,” being deemed of possible propaganda value as a purported British agent. In February 1945, with the Reich crashing down on itself, somebody in the Nazi inner circle remembered Elser, the latter having now been imprisoned for the entirety of the war, simultaneously deciding that he was no longer useful to the hoary English plot scenario. It was either Hitler or Himmler. An order was passed to Heinrich Müller, head of the Gestapo, who passed it to one Eduard Weiter, Kommandant of Dachau, who gave it to an SS sergeant, who carried it out. Elser was killed with a bullet to the back of the head. We can likewise trace specific execution orders passed painstakingly down through the chain of command as late as April and May of 1945 of such high-prestige political prisoners as the theologian Dietrich Bonhoffer and the jurist Hans Von Dohyáni, both active members of the Nazi resistance, albeit arrested a full two years earlier in large part because of an interservice rivalry between the SS and Abwehr. Both survived the vast waves of prosecutions and savage reprisals for various Hitler assassination plots, only to be murdered three weeks before the end of the war, the former humiliatingly stripped of his clothing, and the latter on Hitler’s personal order hanged with piano wire.

In just so painstaking and obsessive a way was charted out the fate of Gertrud Kolmar amidst her fellow German Jews. Here too one begins with simple facts and figures. In 1933, in the year in which the Nazis at first opportunity turned to open persecution and terror against the nation’s Jewish citizens, among its most manifestly assimilated and acculturated, in total the Jewish population constituted eight-tenths of one percent of the population of Germany. That notwithstanding, in city after city, headline-grabbing outbreaks of antisemitic violence were engineered. As to Berlin, the city had always been a cosmopolitan center of general Jewish participation in culture, as well as achievement in business and the professions. Ironically, for Kolmar and others, it now attracted Jews fleeing from more severe forms of antisemitism practiced in smaller cities. Accordingly, as the ill-treatments of the 1930s evolved into the increasingly severe measures of wartime and concentrated encounters in the Nazi capital, the more pronounced became the sheer niggardliness and particularity of their persecutions. First there was the required wearing of the yellow stars and the encouragement of economic boycott and public ill-treatment; eventually came the resettlements into squalid, teeming slum tenements; then, as if at the end of some precise titration of power, came the first mass roundups and transports. In Gertrud Kolmar’s case, this process came to the point where she had been taken away from her home, separated from her father, and conscripted as slave labor in a war factory.

But even then, still to be reckoned with were the particular obsessions of the local grandee—Goebbels, the Reichsminister of Information but also Gauleiter of Berlin—even amidst the effort of total war, it turns out, seething with embarrassment, consumed with his longstanding wish to present his Führer with a capital that could be declared Judenfrei. The main source of his frustration seems to have been that aims of war production stood in the way—namely the indispensability of specialized labor functions being carried out by Jews. Great arguments ensued with Reichsminister of Labor Speer over the relative effectiveness of skilled Jewish workers, with the latter claiming that the laborers in question were irreplaceable with just any other kind of slave substitute. Now doubly irate at hearing Jews praised for expertise, intelligence, reliability, and the like, Goebbels next turned to Hitler, who for the moment sided with Speer. The decision continued to trouble the Führer, however. For his part, Hitler, the transplanted Austrian-Bavarian, had never trusted Berlin, deeming it a sinkhole of political and cultural (read Communist-Jew) corruption. Eventually, after the great initial victories of the early war in the west and east, the matter arose yet again. Hitler newly consulted Sauckel, a Speer subordinate recently installed as head of forced labor programs. Sauckel, naturally eager to please in his new position, promised that he could replace Jewish workers easily. Hitler in turn told Speer he now had nothing to complain about. Reversing his earlier decision, he gave Goebbels the go-ahead for a complete Jewish elimination from the city. At length, on 27 February 1943, thus duly occurred Aktion Fabrik—Operation Factory—a final sweep of Jewish war workers, most of them rounded up at their places of slave labor, deported, exterminated. One of them, of course, was Gertrud Kolmar.

This, then, is what finally appalls about the Nazis—even beyond their enlistment of an entire, advanced western nation state in the service of a cluster of hate-ridden megalomaniacs: the sheer, insane punctiliousness of their maleficence and cruelty. Beyond their carrying out of the most savage and all-consuming campaigns of military aggression and conquest known to history, their truly great crime was the remorseless infliction of suffering and death on millions upon millions of mostly simple, peace-loving, inoffensive people in the world—people nearly all just trying to live the way most of us do: growing up, learning about ourselves and the world, eating good food, hearing music, reading, finding a mate, perhaps experiencing marriage and a family, getting a living, moving into middle age, perhaps growing older—all the while making sure that every human victim on his or her way to annihilation suffered the maximum amount of terror, humiliation, and pain.

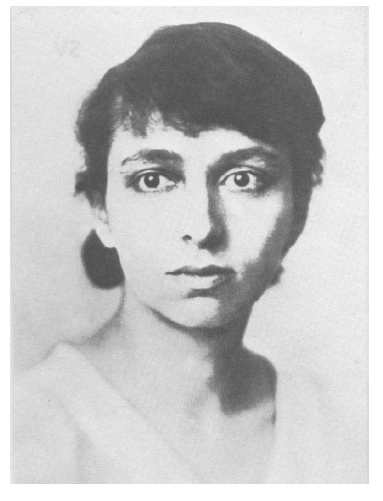

Thus the story of one of those people: Gertrud Kolmar, the poet, who died at Auschwitz in 1943 at age forty-nine. What we have left of her, of course, are the texts. And a street sign. And a small plaque at the place from which she was taken. And, perhaps most poignantly of all, as it turns out, a single photographic image. It is a picture where, somehow appropriately, the poet seems of indeterminate age. She might be in her late teenage years; she might be in her early forties. There is no question that she is a woman of great beauty and intense awareness. The face is that of an individual of immense interest, to whom the world is itself clearly a place of immense, even passionate interest. She is a person in contact with the whole teeming plenitude of existence. One can only say that, to contemplate this image of Gertrud Kolmar and to read the writings she left behind is to understand the fullness of meaning contained in the title of Amos Elon’s magnificent history of the Jews in Germany, 1743–1933. It is to understand, in Elon’s words, “The Pity of It All.”