ON DESECRATION: ANDRÉS SERRANO, PISS CHRIST

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

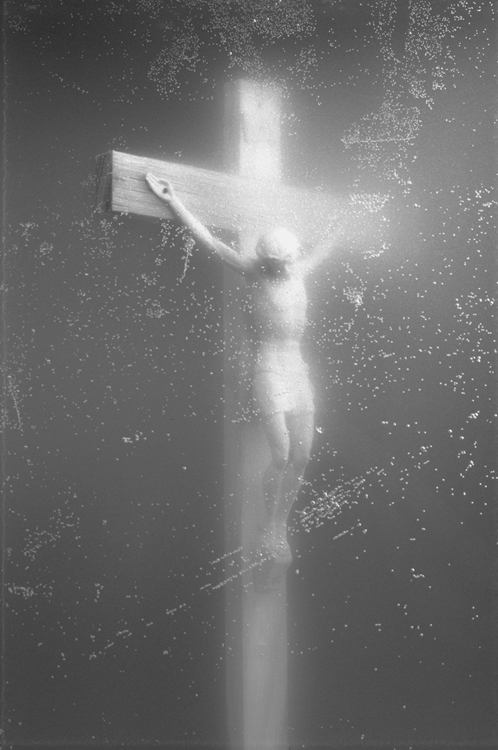

For the last couple of years, cultural critic Ilan Stavans and analytic philosopher Jorge J. E. Gracia have been engaged in a series of dialogues on aesthetics, ethnicity, and power. The result is the book Thirteen Ways of Looking at Latino Art, to be published by Duke University Press in February 2014. Each of their discussions rotates around a different canonical work of art, from photographs to graffiti, from paintings to lithographs, by figures such as the brothers Einar and Jamex de la Torre, Jean-Michel Basquiat, José Bedia, Martín Ramírez, and Mariana Yampolsky. The following excerpt considers Andrés Serrano’s controversial photograph Piss Christ, which was at the heart of a furious debate in 1987 on the United States government’s funding of works of art.

Jorge J. E. Gracia: Serrano’s Piss Christ is perhaps one of the most controversial pieces of art that have been produced in recent times, and for reasons that are quite different from the reasons that other works of art have proved controversial in the past. Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) was controversial because it revolutionized the art of the early twentieth century. A representation of a wild assemblage of women, with faces that emulated African masks and painted in the style that later developed into Cubism, engaged in some primitive rite, was more than the art world at the time could take, used as it was to the relatively harmless canvases of the Impressionists, dealing frequently with landscapes and flowers. It created an uproar and changed forever the course of painting in particular and art in general. One can easily speak of art before and after this work. And then we have the scandal caused by the pictures by Mapplethorpe. His explicitly sexual nudes, documenting ideas that the bourgeoisie hardly dared to dream, were again too much for the art world to absorb quickly. It took considerable digestion, aided by plenty of antacid medication, to get the art community to accept them—the general public is still hostile. But the case with the Serrano was different.

Not that Serrano did not innovate in the purely artistic dimension in his work. He specializes in humors, liquids, secretions, and the like, and Piss Christ follows this original line. But in it he went beyond formality and technique to presents us with something that challenges some of the most deeply rooted beliefs of the Western community. Or does he? Perhaps, in spite of all the noise that his work sparked, he did not say anything that posed the challenge those who protested against it accused it of doing. Perhaps the message of the work is in perfect accordance with those beliefs that he has been accused of undermining. Either way, whether it does or does not, the doubt remains, and that in itself challenges the observer.

The charge is that Serrano did not show proper respect for Christ, the Son of God. He committed a sacrilege, a desecration. That is what some members of the Christian community, particularly members of the clergy, accused him of doing. But one could easily argue that the lack of respect in Piss Christ is not for the divinity, but for the Christian faith. In one way he is regarded as having sinned against God, in the other against Christianity. In either case, the claim is that he went too far. Taking a picture of a crucifix immersed in urine and exhibiting it as a piece of art indicates a complete disregard both for Christ and for those who believe in him. Even in a society where freedom of expression is accepted, this is intolerable, and surely not prudent. Some argue that it should not be tolerated. What makes the act worse is that the work was shown publicly and that this was made possible through a subsidy from public funds, funds derived from taxes paid by the very religious people whose beliefs the work allegedly mocks and insults.

Ilan Stavans: Have you ever pissed on a crucifix, Jorge?

Gracia: I’m sure I’ve done it, although I don’t remember. After all, I come from Cuba and my family was nominally Catholic when I was born. I was baptized and there were crucifixes everywhere. I do not have photos of myself with a crucifix hanging from my neck when I was a baby, but I am sure I had one at some point, and I am also sure that I pissed and the crucifix got part of it. But I guess that does not count, does it? That’s not what you mean. You are asking me whether I, with full intent and as an adult, have ever pissed on a crucifix, or perhaps even whether I have considered doing it.

This is a very serious question that raises the matter of whether Serrano’s piece is sacrilegious, and thus whether the scandal that it caused was justified. For those who hold that pissing on a crucifix is a sacrilege, a major sin, there has to be an intention, and I could not have any intention to piss on the crucifix when I was a baby. But does Serrano’s painting have to be interpreted as pissing on Christ or on the faith and thus as committing a sacrilege?

I think we need to break down what we are talking about in various ways. For one, it is important to pinpoint the identity of the pisser. Is the pisser a Christian, and if a Christian, is the person in question Catholic or Protestant? Or is he or she a non-Christian—a Muslim, a Jew, a Confucian, a Hindu? Apart from this we need to think also about motive. Why would someone piss on a crucifix? Because of personal animosity toward Christianity in general or toward Catholic Christianity in particular? Resentment against the excesses and abuses carried out in the last two thousand years by Catholics against other Christians, and by Christians against other religions? Still further we need to ask what we are talking about when you say “pissing.” For, Ilan, although you have focused on pissing, what we have in Serrano’s work is not pissing at all. Pissing is an act that involves excretion. It is comparable to defecating, although since we are using “pissing” perhaps we should not have any qualms about saying “shitting.” In both instances we are getting rid of refuse from our body.

The act of pissing has important connotations that have to do with power. More in the case of men, whose act is a kind of challenge. It involves holding your penis and pointing it outward, exhibiting the most private part of the male body, and doing it without qualms. Just showing off. Here I have something powerful, a symbol of my machismo. Let me show it to you, the proof of my virility and power as a man. Even when a small, naked child takes his little instrument, arching his back, and points it, there is something impudent about it. We need only look at the famous Manneken Pis, to get the sense of impish shamelessness. It is charming in a child, but in a grown man, it is much more than that. The act, when done in public, becomes a sign of defiance. And when the piss is directed toward someone or something, it says: “Hey, see, I do it on you because you are of the same quality as the piss. You are disposable, worthless, like piss.” To piss on someone is to humiliate him or her, to crush the ego, to put him or her in the proper place, a subservient place, a place of inferiority. It is almost like saying: “You’re shit!”

But the work by Serrano does not present us with an act of pissing! It is a crucifix immersed in piss. Indeed, the title is not Pissed Christ or Piss on Christ, or Pissed Christianity or Piss on Christianity, but Piss Christ. So the piece need not be interpreted as implying that the crucifix, Christ, or Christianity are being pissed on. The meaning of the work could be quite different. It could mean that Christ, and perhaps Christianity as a whole, is immersed in piss, which is something very different. Because then the work does not entail an insult to Christ or even Christianity, but a criticism of Christians, of the Christian community. The art work could then become a cry against those who have soiled the cross and the faith, not a soiling of the cross or the faith. But before we go any further, I’d like to know why you asked me the question you did.

Stavans: I ask the question as I wonder if I could do the same on a Torah scroll, the most sacred artifact in Judaism. The Torah, as you know, is a book. Well, not just a book but the Book of Books, meaning the Bible. What makes the Bible essential is not only its religious grounding—it purports to tell the history of the world from creation to the present—but its moral authority. The Ten Commandments are in it, not quoted once but several times. Their delivery from Mount Sinai by Moses, the religious leader of the people of Israel, the successful people who embraced monotheism at a time of military and theological strife, is presented as a cinematic scene of cosmic proportions. The Torah is written in Hebrew with portions in Aramaic. The text is supposedly written by God in a human tongue, lashon b’nei Adam. Again, would I piss on the Torah? No.

Yet I understand Serrano’s drive. It’s a drive defined by anger. Anger at religion for curtailing human freedom. Anger at what the Catholic Church has turned the crucifix into—an object of oppression. For me the Torah isn’t an object of oppression. I know for sure that orthodoxy in Judaism is about extremes. The ultra-orthodox are against abortion, reduce women to little more than caretakers, and resist modernity as a distraction from the ways dictated by God. They reject scientific, technological, and in general social progress. But a large portion of Jews today have pushed aside the oppressiveness of religions by endorsing a secular view of the world. That break occurred during the Enlightenment, as the French Encyclopedists like Robespierre, Diderot, and others were reassessing human knowledge beyond the confines of the church and as the fighters in the French Revolution of 1789 sought to establish an anti-monarchic, republican system of government. Secularism is not the end of religion, it is simply another modality, even if that modality is categorically denied by the ultra-orthodox, who believe they alone are the keepers of the flame.

Again, secularism isn’t antireligious. Personally, the topic of God is central to my worldview. I’m a weak believer, although I’m not an unbeliever. I’m a rationalist who champions the mind as the map and tool for everything. Faith comes second, but it has a role. What is the function of art in a secular society? To help us define ourselves. To test the waters. Someone like Andrés Serrano is important. But so is the reaction against it. They are part of the same coin. It’s that coin, with its two sides, that interests me.

Gracia: I follow you, but I’d want to distinguish between two works of art: one is the one we have in front of us and the other is a photograph of Serrano pissing on a crucifix. It would be difficult to interpret the last one in a way that wouldn’t be insulting to the Christian faith, or as has been said, a desecration. But the Serrano that we have could very well be interpreted as an indictment of the present state of Christianity, and not even, as you seem to suggest, an indictment of Christianity as a whole, but of Catholic Christianity. Serrano is a Latino and Latino society is predominantly Catholic. I have no idea whether Serrano is a believer or not, and I don’t think it matters either way, for we are not talking about Serrano, but about Piss Christ. What matters is that the context of the work is Catholic. The use of the crucifix with the image of Christ on it makes this clear, because most Protestants are iconoclasts, they do not accept images, a doctrine they share with Judaism and Islam. It is primarily Catholic Christians, and particularly Roman and Orthodox Catholics, who accept images in religious rituals. Catholics kneel in front of images and pray to them. In Catholic theology this is supposed to mean that they are praying to the realities that the images represent, not to the images themselves—that’s how they circumvent the charge of idolatry. Yet, Protestants generally regard what Catholics do with images as idolatry and abhor the practice of adoring and praying to images.

Now, if you are a Catholic and you are concerned about the present state of the Catholic hierarchy—the endless scandals about pederasty, the hierarchy’s alliance and support of cruel dictators in places like Argentina and Chile for example, the banking scandals in the Vatican, and other excesses—the Serrano could become an extraordinarily pious work of art. Its meaning becomes a criticism of the Catholic hierarchy for engaging in, and the Catholic community as a whole for silently condoning, corrupt and anti-Christian behavior. The work turns into a criticism from within, an instrument of the faith, very much in the vein in which Christ behaved towards Pharisees in the Gospels, his cleaning of the Temple and his insults against their greed and disrespect for holy ground. Instead of being sacrilegious, the work turns into a work of piety, a defense of a true Christian faith, unsoiled by the accretions of corruption. But if you are not Catholic, then your criticism, although perhaps valid, might be hostile not just to the present condition of the Catholic community and its hierarchy, but to the Christian community and the very faith. This brings me to the point of asking whether you have pissed on a crucifix, and what doing so would have meant in your case.

Stavans: I haven’t pissed on a crucifix, nor would I. But I have burned a Bible. And not only a Bible but several other major works belonging to the Western canon. Why, you may ask. My answers are manifold. In my memoir On Borrowed Words (2001), I talk about burning Borges’s book in my backyard. This doesn’t have much to do with religion. Or perhaps it does, if one considers parricide an aspect of religion. When I was a young writer, I sought two paths: my freedom as a creator and the absolute, uncompromising knowledge of the writers I admired. Borges was one of them. I had a solid personal library that included every single book of his, sometimes in first editions. I also had some signed copies, original copies of Sur, the journal in which he published many of his essays and stories, and so on. One day, as I was trying to find my own voice, I grew frustrated. The frustration came from the realization that I admired Borges too much. A while back you talked about Socrates. Borges was my personal Socrates. Not only did I know everything there was to know about him, I also dreamed with him. As a result, he controlled me. My writing was an extension of his. So, unhappy with myself—and with him—one day I decided it was time to be born. By this I mean to become myself. The only way I could do it was to exorcize my demons. I did the exorcism like the Holy Office of the Inquisition did: using fire. I profoundly regret the incident. And yet, it set me free. From then on, my relationship with Borges was less tyrannical.

My burning of the Bible is an altogether different story. It has to do with exploring the limits of censorship and the tricks censors employ. You see, we get worked up by the burning of important books. Kristallnacht was a ritualistic act: the destruction of Jewish books by the Nazis. Such destructions are as old as the book as a conveyer of information. As you know, the same emperor who built the Chinese Wall also destroyed all the books in the kingdom. His objective was to start time again, with him at the center, while separating his kingdom from the rest of humankind. In Don Quixote there’s a scene in which books are burned. In Elias Canetti’s Auto-da-fe a similar scene is included. And, of course, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. Anyway, burning books is bad, right? Especially burning canonical books. Yet we’re always getting rid of books. That’s because our culture produces all sorts of replaceable items and books are part of this evanescent material. So why do we get mad if the Bible is burnt but not if the Bible is thrown away? As an experiment, a few years ago I decided to burn a bunch of extra copies of the Bible that had been sitting in my personal library for a long time. I could have donated them to a local library, which is something I always do with surplus books. But I wanted to burn them precisely because the act is supposedly forbidden. And do you know what happened? Nothing. That’s right: nothing happened. Maybe because the Bible means much to me—it is a book I constantly reread, and about which I’ve written much, including the book With All Thine Heart (2010)—the act was ridiculous. Because the burning of books isn’t what gets us angry. It’s the hatred that prompts that burning. Hate is what burns books, not fire. I didn’t hate the Bibles I burned. I simply burned them as if they were disposable trash.

Now I ask myself: how about pissing on the Bible? My answer is: sure. I don’t see any problem with that act either, for the exact reason I’ve just given to you. Pissing is a natural act. We do it all the time. It is considered immoral by some to pee on a sacred object. But not for me. Pissing isn’t immoral and, thus, pissing on the Bible would be fine. And yet, I wonder: what if someone took a photograph of me in the act of peeing on the Bible? My response would be: so be it. Still, my act of peeing on the Bible would now be a public performance, meaning it would have larger implications than a simple anatomical act. I can see myself causing an uproar, needing to explain my action, and so on. Would that stop me? No, it would not. On the other hand, I would not pee on the Bible specifically so that my photograph would be taken while the act is performed. That, in my view, would be reprehensible. Why? Because I wouldn’t be peeing on the Bible; instead, I would be performing in front of a camera. And if I’m performing, then I must be conscious of the acts I engage in because they carry larger implications.

I can empathize with Serrano for peeing on a crucifix if his sense was that the Church was so oppressive that it needed to be criticized. His critique is valid, although it crosses the line into amorality. In turn, let me ask: why is it controversial for Muslims to see representations of Mohamet in cartoons? The answer is that they feel their God is being desecrated. Are they right? Well, they are. But just as I can pee on the Bible and Serrano can pee on the crucifix, with implications of both acts reaching far beyond us, Muslims need to recognize that a pluralistic world, one in which democracy is part of the equation, allows for dissent. And dissent often takes a nasty turn. This cannot be an excuse for violence. The only acceptable response is dialogue.

Gracia: You bring up another dimension of the topic that is also well illustrated by the Serrano. This is the destruction of objects—in your case, books, the Bible; in the case of Serrano’s work, its destruction by a mob in Avignon, where it was being exhibited. By the way, the destruction of art works is not unusual. We have the case of the Taliban destroying old carvings and statues in Afghanistan in their zeal to adhere to an uncompromising form of Islam. And we have the case of the destruction of a work by Leon Ferrari in Buenos Aires by a mob of the faithful, guided by a priest.

The law is quite clear in most of these cases. A lawsuit was brought by Ferrari in Argentinian courts and he won the case. The case of the Taliban was generally condemned by the international community. And I do not know what happened in the case of the Piss Christ. In any case, the law punishes the destruction of private property belonging to others who are not the destroyer. We destroy all kinds of things we own, as you did with the Bible, and I’ve done with photographs, personal memorabilia, papers I’ve written, and so on. And the law, of course, does not interfere. Legally, no one has the right to destroy the Piss Christ but Serrano. So those who did destroy it are guilty of an unlawful act. But the interesting question is the moral one, for the law is rather limited in its scope, and we frequently consider it right to break laws that prevent us from doing something we believe is right. The question is whether it is right for us to destroy objects that insult our beliefs and our persons when they do not belong to us. Do I have the right to destroy a caricature of me that some artist made, when I take it to be insulting and prejudicial? Perhaps, but only if it is proven that the caricature harms me in some way, and it was intended to harm me. What about religion? For Protestants and Jews, the depiction of God in some image is a sin. Idols are unacceptable, and following Moses’ example, it would seem that they are entitled, morally, to destroy them, aren’t they?

From this it follows that those who do will be rewarded in heaven for their courage in standing fast on their principles, even if they are punished by human laws for the destruction of property they do not own. Accordingly, the Taliban are to be praised, and so would be Protestants, if all of a sudden they went on a rampage, destroying images and statues in Catholic churches. After all, aren’t they behaving according to the mandates of God, as they see it? And should we punish them for acting according to their conscience?

If I follow you, you think that they ought to be punished for acting on their beliefs. And your suggestion is that they need to understand that living in a pluralistic and democratic society entails both abstaining from actions such as the ones mentioned as well as being punished for those actions when we commit them. But this reason will not sound good enough to those who are ardent believers. It certainly did not prevent the mob in Avignon from destroying the Serrano. Tolerance and democracy did not seem enough.

Stavans: They might not seem enough but that’s the only thing we have: tolerance as a value that fosters coexistence. Yes, the destruction of art is a feature in human history. This is as it should be. The same Darwinian laws that govern the animal world govern the artistic world. What survives is the result of a number of factors. Had every single artistic piece ever produced endured through time, we would not be capable of appreciating what we have. Just as forgetting is an essential component of remembering, destruction is needed for creation.

In this regard, I want to invoke one of my favorite novels, one that along with Don Quixote is, in my view, the best Hispanic civilization has ever produced: One Hundred Years of Solitude, another contingent work that defines who we are. One of the leitmotifs in García Márquez’s novel is the tension between hacer and deshacer. The characters, both male and female, create in order to destroy, and destroy in order to create. It’s an eternal cycle, as old as Penelope’s sewing in The Odyssey.

But I want to take exception with something you said, that the only person who has the right to destroy Piss Christ is Andrés Serrano, the artist who created the piece. I disagree with you wholeheartedly. Once a work of art is created, it no longer belongs to its creator. It is part of the human heritage. That is, it has no individual owner, only a collective owner. Yes, Jorge: while I believe in artists as owners of their oeuvre in economic terms (art is private property and the copyright is in the hands of the artist), I don’t believe that artists, once their work is out and about, are any longer the owners of what they produced. They were the conduit—the secretaries, if you want to use that image. They allowed the work to materialize. But that materialization, once it is part of the public domain, leaves them out of it. Their name is only a reference: Ah, Serrano, the artist who made Piss Christ! That’s the way of seeing it, and not: Ah, Serrano, the artist who owns Piss Christ!

Gracia: Now we are getting into areas in which the dialogue is becoming heated because we may disagree. So let me start where you started. You mentioned earlier that tolerance and democracy are sufficient for preventing the destruction that iconoclasts bring about. To which I responded with an argument to the effect that they are not, because tolerance and democracy are not convincing goals to those who engage in wanton destruction of art pieces that have messages with which they disagree or that they perceive to undermine their beliefs. To this you answered that “[T]hey might not seem enough but that’s the only thing we have: tolerance as a value that fosters coexistence.” I think that actually by saying this you have already gone beyond tolerance, that is, you are providing grounds for the desirability of tolerance. Tolerance becomes desirable because it is a value that fosters human existence. The reason for tolerance is not tolerance for its own sake, but because it is the key to something more basic, human existence. And indeed, this is where I wanted us to go. For human existence is certainly a value that should appeal to everyone. I say “should” because it does not actually appeal to some people, either because they are crazy or because they have been corrupted by indoctrination to such a degree that they have forgotten that existence is a prerequisite of any other good. Think of suicidal bombers, for example.

But I would like to refine the point you make by noting that the only way to convince iconoclasts is by making them see that what they do goes against their own interests. I do not think arguing with them that destruction is bad will do any good. But showing them how their destruction of what they hate can bring about the destruction of what they love, including their own lives, I think has a chance of being persuasive. And the point you make about Darwinism emphasizes it. The survival of the fittest is the law of nature and so it also rules humans and the artifacts we create. This is why showing that certain behavior is against our basic drive to live is the best way to convince us to change it.

So perhaps our disagreement did not turn out to be a disagreement after all. In fact that also goes for the other disagreement that you mentioned, namely, that the artist is the owner of a piece of art and, therefore, the only one who has the right to destroy it. The reason I believe there is no disagreement is that you grant that “economically” the artist is the owner of the piece and therefore has the right to destroy it. After all, I followed my remarks by saying that the interesting point is the moral one, not the one ruled by law. By law, only the owner of something has the right to destroy it, be it art or something else, as long as the artist has not sold it, that is, passed on the right of possession to someone else. When artists sell their works, they lose the right to them. To repeat, though, the interesting question concerns the moral issue: Who has the moral right to destroy an art piece, regardless of who owns it?

You seem to suggest it is the “real” owner—what I would call the moral owner—of a work of art, to which you add that it is a collective, although you do not specify the collective in question. And you do not for a reason, for humankind is both a collective and composed of many collectives. The overall collective is the human race. But this would not solve the problem of the right to destroy certain pieces of art insofar as the human race as a whole does not agree with the destruction of particular pieces of art, as the outcry against the Taliban showed. Then it must be particular collectives, but which? A nation, an ethnic group, males, females, members of a religious group, transsexuals, those who value the piece, those who understand it? What if the piece of art was created and has never been shown? Where is the collective then? Maybe only the author knows of the piece’s existence. Another possibility favored by idealists, romantics, and some of the religious is that the real owner is a kind of divinity, but this is surely not acceptable. In short, I am afraid I have more questions than answers. As Socrates would say, I have reached a state of perplexity. He claimed that to be the beginning of wisdom, but at the moment I feel as if I knew only one thing, that I do not know.

Stavans: I, instead, do know. I’m thrilled that you’ve invoked—and done so eloquently—the concept of moral owner of art. In my view, all of us might be morally connected and morally reflected in the work of art, yet none of us has the moral right to destroy it, no matter how offensive that art might be. The moral argument collapses when the legal question is put forth: only the artist has the right to destroy his work. Not even a collector who has bought it has that right. For even though the acquisition of the work has made it pass from the artist to the collector, the artist remains responsible for it. A collector of Serrano’s Piss Christ might have bought it because she loves the piece. Or she might have bought it because she hates it and wants to keep it away from other people’s eyes. At any rate, it would be false to suggest that because that collector owns it, the ideas represented in the work are now hers. They are solely the artist’s. So what happens when the artist dies? No one is entitled to destroy the work. It belongs to everybody. Its durability is sealed in the human conscience.

Gracia: I think you have in mind the idea, and not the artifact. It is this idea that is, or should be, beyond particular ownership. But this opens the door to another labyrinth, surely without end. Let’s leave entering it for another time.