RETHINKING BONNARD: THE NUDE AT HER TOILETTE

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Can we say Reflection in the Mirror (Effet de glace) is prototypical? Completed in 1909, the painting is an early version of a theme—the female nude at her toilette—that captivated this artist’s attention, a fire he’s drawn to, throughout his career. But what makes this particular example appear identifiable as a bona fide Bonnard can’t be the subject matter per se, because Degas, Renoir, and Picasso, to name a few, have also shown a fondness for exploring artistic possibilities that focus on a young woman, nude or partially robed, performing one of the intimate, ancient rituals of bathing, toweling off, combing one’s hair, and dressing. (Most such painters were male, but we don’t want to forget Mary Cassatt.) No, it isn’t the subject matter and the hint of a narrative starting to unfold—the lithe brunette bending forward at the waist, her high breasts pulled free by gravity, the metal washtub waiting for her to step into the water, a hairbrush waiting on the shelf, the pot of tea and tea cups on a tray resting on the floor in the background that distinguishes Reflection in the Mirror; it is more the way the scene is painted—what colors are used, how the colors have been arranged, and how individual strokes of paint are formed. In these formal qualities, we can see at a glance: yes, the painting is prototypical of Pierre Bonnard. French painter. 1867–1947.

The scene depicted in Reflection in the Mirror is simultaneously intimate and immense. If you recall what Gaston Bachelard philosophized about in his seminal volume The Poetics of Space, you’ll recognize that Bonnard reached the same conclusions artistically in this painting a few decades earlier: small physical spaces (a bathroom, the top of a shelf, the underside of an empty chair) can open cavernous emotional realms in the imagination. Here, Bonnard’s picture (not all paintings are pictures, but Bonnard’s always are) pairs the theme of the bathing nude with another of Bonnard’s favorite motifs: a view in a mirror. In this case, the reflection dominates the composition, only a sliver of a shelf and narrow glimpse of surrounding wall appear at the outer edges; Bonnard has painted these in neutral tones of yellowish greens, pale pinks, and paler oranges. This is an early Bonnard, and so the luminous patches of color are circumscribed: the warmth of the figure’s skin, the orange-gold patterned floor, and, most vivid of all, the light cobalt blues that animate the tea cups, the floor of the wash basin, and, especially, a thin blue arc that curls around a curious yellow shape—a wash cloth? While photographs frequently contain portions of forms that can’t be confidently recognized, not so with paintings. Bonnard is rare in his wish to show a world that contains forms not fully formed. Even with the forms that are readily nameable, there are no hard edges; the forms are a bit unsettled. Mass is energy, energy mass; light pulses. Colors are energized. Paint strokes nestle together, shapes begin to dissolve (or, is it: shapes have not yet congealed fully?). We see the world as feathery, slightly blurred. What provides such a look? Peripheral vision—the expansive imagery that stretches away from the center of foveal vision—looks like this. Also, the vision of mild myopia; Bonnard wore wire-rimmed spectacles—do we hypothesize that this is how the world appeared to him when he took his glasses off? Also, the vision at a great distance appears slightly out of focus. Bonnard concocts a paradox: now we are free to focus on the peripheral view; now we face closely the view from afar.

A curious effect: the power of colors to shift identities exists in inverse proportion to the differences in the colors themselves. A choice of colors distinct in hue, saturation, and/or value (three fundamental properties of color in paints) may appear dramatic—compare pale yellow to dark blue. However, the eye perceives this contrast easily and consistently. Bonnard’s compositions are often characterized by color choices similar in some gradient: pale yellow next to pale orange, for instance. Now the value, saturation, and hue of juxtaposed colors are so close that the eye (and the mind behind the eye) can’t pin them down with certainty. The smallest modulation and the yellows appear lighter here and darker there, next to the orange.

Color is always perceived relative to and influenced by the colors in proximity. Subtle, neutral colors (off whites, pale violet, grayish tints, and so on) are easily unsettled. Art students are familiar with these dynamic properties of color through well-known and widely adapted color exploration projects designed by Josef Albers. But before Albers codified the possibilities as studio exercises (make two different colors look like one; make one color look like two colors; create luminosity; and so forth) Bonnard offers us a world—a canon of paintings—bedazzled by an aesthetic vision built on these effects.

Painting that warrants sustained interest requires memorable and emotionally resonant visual form; a great painting achieves a profound linkage of style, technique, and theme. The great painting sings. Greatness also requires the active involvement of the viewer. The viewer joins the painting to participate in the process of performing meaningfulness. This may seem counterintuitive. One may be tempted to equate power in artistic effect as stemming directly and in proportion to the artist’s success in calling all the shots, in controlling fully the effect (the meaning) of each and every square inch of the canvas. In this view, the most praiseworthy painter would be the one who picks up the painting and knocks the viewer over the head. How’s that for controlling the effect! What strategies did Bonnard bring to bear to create an active relationship between the viewer and the artwork? Bonnard’s exploration of the plastic element of color creates a condition in which the viewer is inspired—and put into a position—to conduct her exploration of color, an exploration which occurs first while looking at one (or more) of Bonnard’s paintings, and, secondly, while continuing the process of looking at the world. The subtlety of Bonnard’s chromatic concoctions—central to each painting’s composition—creates a relationship with the viewer: the viewer actively explores the changeability of color, sensing that color is forever about context. Color is central to the composition, and the quality of color in perpetual flux is central to the theme: time and space flow endlessly, ceaselessly . . . even in an image of a nude at her bath, the front surface of a painting that is, in fact, static, whose rectangular composition never changes. Or does it?

As other scholars have noted, Bonnard’s approach to painting is panoramic. Even in a small interior, he shows us the view of someone who looks around; the painting offers more than the (classic) view in one single, fixed direction. The view in looking at a Bonnard is immersive: the viewer is embraced, surrounded by the scene. One looks in different directions, much as one would scan a real room upon entering through a doorway. Scanning around, of course, makes the relationship of viewer to artwork increasingly interactive (Remember? That’s the criterion I’ve put forth for what makes a great painting.) But this fact—that one scans around a Bonnard painting—is something of a paradox. Like Edgar Degas of the preceding generation, Bonnard was a French painter who was enamored with taking photographs and using them as sources inspiring his own compositions. A standard photo is the antithesis of scanning. It is a fixed view, in one direction. So, it is a puzzle how Bonnard can look to a photograph as an initial source for composing a painting that is panoramic. In the snapshot photo, taken by Bonnard in approximately 1908, the model stoops nude in a metal washbasin; she is bathing: the scene is entirely out in space, in depth. In the oil painting, created eight years later, circa 1916—Nu au tub—space has become a plastic, flexible element. The dimensions extend outward, down, and back—from side to side, from front to rear—so that the scene puts its arms around the viewer, giving the viewer a hug, so to speak. And, at the same time, the viewer is pulled forward, into the scene. The view is looking down into the tub, down at the head and shoulders of the nude female. Only forms in the distance, like the far wall, are upright, in deep space, where, according to Bonnard, “the view of distance is flat.”

Bonnard allows (no: it’s stronger than that: he makes it happen) that the picture unfolds slowly. Like walking into a room for the first time (or after a long absence), the viewer coming upon a painting by Bonnard takes in the scene, over time. It doesn’t happen in a single instant; there is a small temporal passage in which the process of looking around takes place. Viewing a painting by Bonnard, our eyes light upon various focal points one after another, and, then, gradually, we slowly build up an awareness of the whole, we slowly can hold the plenitude of visuality. In an exhibition, pausing before Reflection in the Mirror, for instance, I glance first at the vivid blue in the lower center of the composition, then my eye is attracted up to the tilted face of the figure, then I scan down the expanse of her body, then my eyes leap—over to the white shape (a curtain?) on the right, then back across the entire composition to the hairbrush on a shelf at the lower left. Now I am catching sight of the delicate manner in which the artist has painted in small white strokes the individual letters of his name B o n n a r d just above the mirror. Seeing is looking in various directions, and seeing is remembering what one looked at earlier. French poet Paul Valéry observed: “To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees.” (And paraphrasing Valéry, Lawrence Weschler titled his perceptive analysis of contemporary American artist Robert Irwin: Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees.) Our observation that seeing is remembering—as the viewer constructs a holistic understanding of the view, which cannot be perceived as a single gestalt—doesn’t contradict this; it only enhances the statement with another insight. I have no doubt that another viewer approaches the painting in a modified manner, so that the composition unfolds in a different sequence of directed glances; just as my own approach to seeing Reflection in the Mirror will be altered the next time I look into its surface.

Peripheral vision plays an important role in this process, just as it does in scanning a scene in real life. In creating a 1931 version of the pairing of the two beloved themes of bathing and reflecting—Toilette (also entitled Nude at the Mirror)—Bonnard means for us to notice some details and aspects of the image slowly, lovingly, so that it is only after some time that we find ourselves thinking, yes, there’s some orbs of fruit in the mirror on the left: I wonder why I didn’t notice those before? And, now that I look closely I see those pieces of fruit are reflections of the actual fruit balanced on the table, off to the right . . . These details register first through one’s sideways glances, and then you give them your fuller attention as you turn and focus your eyes and attention in a certain direction.

What of the painting itself? Did Bonnard the artist glance at each of his paintings-in-progress from an angle? As an artist whose aesthetic vision promotes the periphery, would Bonnard have chanced to look at his own art from a similar vantage point? And how much control has he exercised in creating the painting: did he mean for us to move along its length as we study its various aspects, sometimes moving position and sometimes standing still but moving our head, even tilting it? I want to argue that the answer must be, decisively, yes! And, doing so—if we move around the painting as a physical surface (like a planar object), and move our heads and look in different directions: what then? How does the painting appear now, how does it function?

Curiously, paintings in our own era, in which the view of the artwork illustrated in a book or on a computer screen provides a convenient and habitual manner of viewing a painting squarely, the artist in his studio, and the viewer in the museum or gallery, or the person chancing upon a painting hung on a wall in a home—in all these cases the painting is seen, almost without exception, first from an angle. The approach to a painting is most often coming at it sideways. We see it perhaps out of the corner of one’s eye, while one’s vision is trained initially elsewhere.

Painting is vital if and only if each successive generation refreshes the strategies available for a viewer’s interactivity as central to the process of giving and receiving meaning. Our involvement with paintings from previous eras gains new vitality as our approach to contemporary paintings shows us new ways back into the past. And vice versa. A feedback loop must be maintained for any art form to stay relevant to the culture. In the case of Bonnard, we want to unravel how he saw his own paintings—how he meant for his paintings to be seen. And, second, we want to gain knowledge of how now, at this point in cultural history, we can look at his paintings. Looking at isn’t the best way of expressing this process, it would be better to say looking with his paintings: each painting functions like a pair of eyeglasses with its own unique prescription.

Bonnard constructed his paintings to emphasize those qualities—that they are panoramic, that they were created based on a changing line of sight, that they bring the viewer into their midst, that they were imagined in terms of a moving position, that they place a premium on a plastic conception of space. Some examples: The Terrace at Vernon (La Terrasse de Vernon) (c. 1928) is a gorgeous huge oil on canvas, over eight feet in height and ten feet in length. It isn’t natural, and Bonnard certainly didn’t plan that a viewer would walk up to such a painting with her eyes closed, and then open them and remain standing, frozen in just one position, at a place perpendicular with the middle of the painting, and look at the entire painting along one consistent line of sight. No, the viewer moves along the painting, scanning its surface, and looking intensely at those portions of the painting that are close at hand. In this process, the perspective extending into space along the porch on the left side is seen as if that extended straight out from the viewer. Moving to the right, along the width of the painting, other aspects take precedence, and our view aligns successively with them. If we stand in front of the far right side of the painting, that portion of the image is square to our looking, whereas the porch in depth on the left is now viewed at an oblique angle. Bonnard surely meant for this changing perspective to occur; and, doing so, the painting seeks and rewards our increased interactivity, both physically and mentally. Our perception alters, and so does our conception of the painting’s sense of space. Just as the viewer takes in the scene over time, the scene takes in the viewer over time.

What happens to the process of looking in the case of one of Bonnard’s mid- or small-size easel paintings, such as Reflection in the Mirror (just a shade under three feet wide)? When I stand comfortably in the approximate middle of the painting’s width, at a distance of ten feet, I can take in the entire composition in the center of my (foveal) vision. This is equivalent to how an ordinary 35-mm camera would capture an image of the picture, and this is how the painting looks in an illustration in a catalogue of Bonnard’s art, with the book held open at arm’s length. But, just as in the case of the mural-sized painting La Terrasse de Vernon, standing in one position with one’s eyes locked in one direction only is not the way Bonnard conceived and created the painting; it is not the way he meant for the painting to be seen; and it is certainly not the way we now should look at the painting. It is one way to look at Reflection in the Mirror, but this should not exhaust our ways of looking. Among our ways of exploring the visuality offered by the painting should be standing at different positions, looking at different aspects of the painting in detail, of turning one’s head, or seeing the painting squarely and also allowing it to take shape in one’s peripheral vision. And, last but not least, one needs to look, if one is to see the painting in its entirety, from a variety of positions: up close and far away, dead center (squarely), from the left, and from the right.

Of these positions, it is most significant for us to dwell at some length on the two angled views. It is a historical fact that over the course of the history of paintings there has been a shift. I generalize here, but the basic concepts are key: early in its history, painting (like sculpture) was seen from many positions. Then, slowly, for several reasons, painting became an art form that focused increasingly on the rectangular format, and, then, the process of looking at rectangular paintings focused increasingly on viewing them squarely (with the line of sight perpendicular to the picture plane). It was during this change that the concept of anamorphosis became popular, something of a parlor trick to entertain viewers. Painters and their viewing audience recognized that the view from a slant collapsed the horizontal dimension of forms painted on the surface: moving increasingly to a more angular view, the picture on a surface appears increasingly scrunched. The development of anamorphic imagery took advantage of this—hiding in the squared representation an image that would only gain its complete normal shape when viewed at an extreme angle. The most famous example in art history must be the unsettling anamorphic image of a skull, inserted as a secret in Hans Holbein’s portrait (1533) known as The Ambassadors. While the development and then wide deployment of linear perspective played a large role in this shift, other factors—the development of easel painting, the premium on portability, the development of photography, the development of printed illustrations, the development of the white gallery aesthetic—all exerted varying influences. Again, I simplify, but from the middle of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century, the only way to look properly at an easel painting (and the vast majority of paintings then were easel paintings), to appreciate it aesthetically, was dead on. Within this paradigm, the shape of the painting is, must be, a perfect rectangle. I call a rectangle perfect when the view of the rectangle, on the retina, presents both pairs of opposing sides of equal length, and all angles are right angles. This is not a rectangle seen from an acute angle: what, in geometry, is identified as an isosceles trapezoid. While the history of the viewer’s physical position in relationship to a painting is complex—and any change in the physical relationship signifies a concomitant change in the cognitive relationship—what I want to clarify here is simply: painting as an art form started as non-rectangular and viewed from any angle; we passed through various stages in which the predominant paradigm gradually favored rectangularity and, more slowly, the square-on view; now we are passing into a new paradigm in which painting is, again, frequently non-rectangular and viewed from any angle. Recent artists who exemplify this latest shift include Jonathan Borofsky, Elizabeth Murray, and Jessica Stockholder.

Seen fully, how does Reflection in the Mirror appear? It is significant that the image in the painting becomes flexible, space is plastic, malleable, by the action of the viewer in moving around and looking at the painting from a variety of changing positions. For instance, when looked at from the right side, the primary view is into the room reflected within the mirror. The viewer conceives of himself (or herself) off to the right side, looking into the mirror at a sharp angle, and, through this view, the bending figure of the nude can be glimpsed.

Now, when I change my position, crossing to the left side, and look at the painting, the view is quite different. While the painting itself is not three-dimensional (other than as a shallow object, the depth of the painting’s stretcher and frame); the visual dynamics in concert with the movement of the viewer’s looking becomes plastic, becomes a metaphor for three-dimensionality. The view from the left creates the illusion that I now look straight into the mirror itself. I am looking at the mirror directly, square on. My own invisibility is clearly apparent. From this angle, the physics at play is altered: I should be seen somewhere in the mirror; I should be there, in the mirror, close to the bending female. The intimacy of the scene has been ratcheted up now to a fever pitch.

It is surprising, and the effect is subtle at times, but to the sensitive viewer—and surely there was no more sensitive viewer of a Bonnard painting than Bonnard himself—one of his paintings calls for, and rewards the active involvement of, the viewer in the exploration of the spatial arrangement of the picture. This spatial arrangement changes as the viewer changes position. Such a painting is not at all like a page of prose: the meaningfulness of the prose, the arrangement of the words (like the words on this page), do not change one iota of grammatical, semantic meaning as I read the page from straight on, from the left, and slightly from the right. Such a changeable verbal art would take the writing into the domain of concrete poetry.

At the height of his powers during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, Bonnard’s distinctive artistic vision was shaped in response to the pressures of his psyche and by his understanding and response to the world. An extended exploration of his art reveals his achievement as one of the supreme modernist painters, a worthy rival to Matisse and Picasso. While his gifts were more limited in range than those of the other giants of painting at work in France during the same era, Bonnard possessed the genius to explore with almost infinite patience the same subject matter that was always close at hand (views of the interior of his home, his wife, his garden, himself). The results were incandescent. The results are incandescent.

You can see for yourself: Nude in the Bath (Nu dans le bain) (1936) is a glorious painting. The standard art historical analysis points out the obvious facts: Bonnard has, yet again, made a variation on the theme of the nude female at her toilette. This time she is enclosed: she is enclosed by the walls of the bathroom, she is enclosed by the walls of the tub, she is enclosed by the water in which she is submerged up to her neck, and she is enclosed psychologically—and yet, she is utterly, undeniably, splendidly free. The woman appears both lost and found in her own thoughts. Like the room and like the water, light physically, metaphorically, and, yes, spiritually passes through her. There is a transfusion happening. The woman and the bath are as much windowpanes as the golden glowing grid of glass in the upper left corner of the composition. The entire image, and each form within it, appears translucent, luminous, and permeable.

The painting itself is an apparition. Like all powerful apparitions, it is anchored partially in the past. Sasha Newman, a curator who helped organize the splendid traveling retrospective exhibition of Bonnard’s work in the mid-1980s, had this to say: “The woman is enclosed, as if in a shell or a womb. She floats in the water that surrounds her, in the manner of a Monet water lily or a drowning Ophelia. She is not of this world, nor a part of the continuum of time as we know it. Neither dead nor alive, she exists in her self-enclosed realm. . . .” I want to extend Newman’s analysis in several directions: metaphorically, metaphysically, and mathematically. Bonnard’s exploration of the plastic elements of space and time gives shape to each of these levels of interconnected meaning.

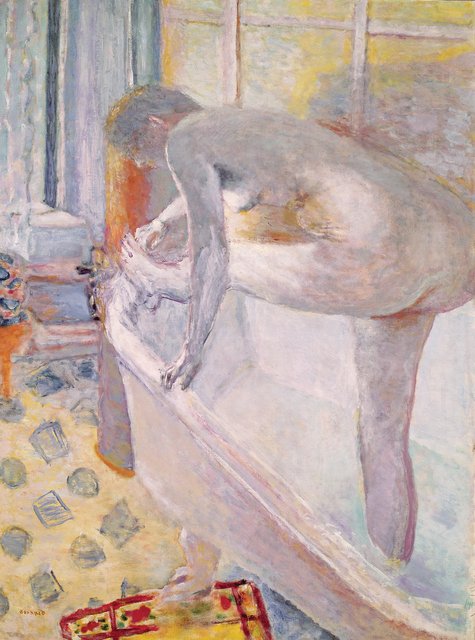

The woman is enclosed, in a bathtub, as if in a shell or a womb or, I would add, a casket or a tomb. One of the more idiosyncratic aspects of Bonnard’s art—and like any idiosyncrasy, it can be a portal to an insight into what makes him him—is his inspired envisioning of the undeniably eccentric, at times difficult, Marthe. Marthe de Méligny (her given name was Maria Boursin) was Bonnard’s lifelong companion, his primary female model, and his perennial muse. They lived together starting in 1893; in 1925 they married. The hours she spent at her daily bathroom rituals are legendary. While she (must have) aged over the decades, Bonnard continued to paint her, again and again, in her youthful beauty. By the end, she appears in nearly four hundred of his canvases. That is Marthe arched over, one leg raised, standing in the tub in the great painting Pink Nude in the Bathtub (Nu rose à la baignoire) (c. 1924). (Note: a wonderful essay could explore the relationship of the composition in this Bonnard to similar compositions in Caravaggio’s Narcissus (1598/1601) and the contemporaneous David with the Head of Goliath.) Marthe surfaces again a year later in Nude in the Bathtub (Nu dans la baignoire)—on the painting’s surface her legs are vertical, straight as partially opened scissors; as she lies in her bathtub, a male figure in a bathrobe (a portrayal of Bonnard by Bonnard) partially enters the scene at the upper left.

In addition to creating paintings in which his wife Marthe served directly as the model, Bonnard made numerous other paintings in which the memory of Marthe, perhaps with another female as his real-time model, serve as the inspiration. Nude in the Bath (Nu dans le bain), painted in 1936, is such an image. The female in the water is youthful—an image, like a memory, in which Marthe has not aged. We must remember: Bonnard and Marthe have been a couple at this point for forty years.

If we look at this painting from an active process, a startling transformation occurs. Viewed straight on (in the classic, squared up position), our perception emphasizes that we are looking down into the tub, which extends horizontally in both directions. If we move to the left to look, the emphasis is on the nude as an other: we are cast in the role of staring at her legs and torso; the bluish-purple sequence of wall tiles immediately to the left of center are now a dominant feature of the painting’s composition. If we move over to the right and look at the painting, we now take the vantage point of the nude herself. We look along her line of sight, down the length of her body, and then directly into the gold window that is located—in this position—past her delicate, crossed pink feet. The entire painting is foreshortened slightly, to such a degree that the soft dark thatch of her sex now appears in the exact center of the composition. The conception of the painting is non-Euclidean: space and time in the bathroom, within the bath itself, are curved, as curved as the nude herself.

A painting by Bonnard entices the viewer: to circle it, back and forth, to look this way and that, to stand over here and then over there, to move closer, so that ultimately the viewer is encircled by the painting, and, doing so, to see and be in the world as Bonnard saw and existed in his world. Can we be sure that Bonnard meant for us to know flexible modes of viewing his paintings? The evidence is in the paintings: for example, there is the small anomaly of the chair back in Corner of the Table, from 1935. In the upper right corner of this small, charming painting, showing a still life arrangement of bowls of food on a table, a chair is shown at a peculiarly steep pitch. The horizontal slats of the chair are nearly vertical. Bonnard gives us the view of a painter who is looking at his world from different angles, different positions. More powerful evidence, I think, can be found in two paintings that are other explorations of the theme of the female nude at her bath. Both Large Nude in the Bathtub (1924) and Leaving the Bath (c. 1926–1930) are dominated by solitary bathers standing in a tub; in each composition, the nude has one leg raised, her back is bent forward, and the body cuts back into space, at an angle away from the picture plane.

Large Nude in the Bathtub (or, as Bonnard would say: Grand nu à la baignoire) is a marvel of luminous color (see page 482). The entire surface of the painting pairs various tints and tones of pale cool lavenders played off against cool bluish whites and warm, unsaturated yellows and yellow-oranges. In a few carefully chosen areas the warms become deeply saturated—in a patch along the wall, on the floor, a streak along the nude’s spine, and in an arc that lines the underside of her uplifted leg and derriere. For me, the anamorphic dynamics at work in this painting are beyond question: when I view the painting square on, the torso “reads” as somewhat flat to the picture plane and slightly elongated. (In the case of Leaving the Bath, this elongation is more pronounced, so that the square-on view looks somewhat strange, concocted, and idiosyncratic.) When I move to the right and view the painting, the illusion of the figure’s mass slanting into three-dimensional space is far more powerful, and, of course, actual. The painting is truly three-dimensional: the figure’s derrière looms large near to me; her delicate uplifted foot is deeper in real space and deeper in the fictive space of the painting. As a viewer, I look at the scene from a position directly behind the figure; as if I stood at the back of the tub and stared over the figure’s shoulders roughly (delicately?) along the line of the spine. The dimensions of the figure are reduced in the horizontal dimension (because the painting is now seen at an angle): and this anamorphic view corrects the figure’s proportions. When I move to the left, the figure’s proportions are again diminished slightly in the horizontal axis by the anamorphic process, and again the proportions are corrected. Now I am looking at the figure from the side, as if I were standing farther to the left of the tub. From this vantage point, a wonderful, perplexing, paradoxical optical illusion appears: the figure’s uplifted foot is, in the fictive space of the painting, farther from me than her (beautiful) bum; but in the world of reality her foot is close and her rounded rear is farther away. Near is far. Far is near. Reality and the fictive world of the painting meld closer and disjoin simultaneously. Of his art, Bonnard stated: “There is a formula, which fits painting perfectly: many little lies create a great truth.”

Let’s repeat what we have learned: A great painting involves the viewer’s interactivity in the production of meaning. Cubism—building on the example of Cézanne—explored the depiction in painting of a flattened representation of changed views of a subject. This essay would add to the discussion: Bonnard allows us to explore the depiction in painting of a flattened representation of changing views of a changing subject. Doing so, Bonnard gives us a new view of themes as ancient as myth: the nude female at her toilette; the view in a mirror; the intimacy of space and time. Bonnard started laying in the first strokes of color in 1941 for what became his final great version, the five-foot wide: Nude in Bath and Small Dog (Nu dans le bain au petit chien). Marthe died in 1942. The painting was completed in 1946. Bonnard passed away in 1947. My favorite aspect of this painting, now in the permanent collection of the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, is the fact of the dark, glowing, reddish shape of the basset hound on the small perfect rectangle of pale pinks, yellows, and whites. The square-on orientation of the small rug and the dog resting on the rug anchors this element within the composition in space. As the viewer moves around, looking at the painting (from the right, from the left, from the center), the entire composition appears in flux, except for the dog on the small rug. The perfect vertical and horizontal edges remain steady. And the dog’s eyes follow our movements, she (I sense the dog is female, but perhaps I’m mistaken) stares directly out at the viewer; or, no, the dog’s eyes are dark, as if the animal stared at a mystery beyond a view into our everyday reality. The dog appears identical in breed, coloring, shape, size, even to the pose it takes on the small towel, as the obviously beloved pet who anchors the image in the mirror in Dressing Table and Mirror (La toilette au bouquet rouge et jaune) from c. 1913. There’s Marthe, again: camouflaged in the deepest recess, the frame of the mirror slicing off her head, or, alternatively, our view of her head. Separated by three decades, the paintings merge: each is another variation on the theme of the intimacy of la toilette, the profound visual attraction of luminosity, the symbolic (spiritual) significance of silence, and the endless poignancy of denying death—by doing what one can to stop the flow of time: by painting.