MIDLIFE RUMINATIONS ON LOUISE BOURGEOIS

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

This spring, living in Berlin for half a year, I’ve developed a strange habit of talking to my mother-in-law in my head. This is strange not in itself—I’ve been doing it for a very long time—but because of the subject matter: I talk to her about female artists and specifically the most daring ones, the ones who deal in the abject, women such as Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois. And this makes both no sense and all the sense in the world, given that Millie has no interest in such artists and would probably find their work at best perplexing, at worst disgusting. And that is, presumably, precisely why, in my head, I insist on engaging her in conversations she has no interest in, no capacity or desire for. I have a tendency to bang on the very doors that are most definitely closed to me.

I had a distressing incest dream the other night, which I tried to banish the next morning by considering that there is always a Father who lingers within us, leaving his trace; that this is the trauma of the culture as well as that of the individual; and that I am no more perverse than any other daughter. So here I am in the museum—the Sammlung Scharf-Gerstenberg, in Berlin, a month after the great sculptor’s death—with Louise Bourgeois’s sculptures, and in my head I’m talking to myself, to my mother, and to Millie. I don’t talk to my father because Bourgeois’s work makes me think of the father as someone out of the way, or to be got out of the way if he isn’t already. After all, Destruction of the Father was the title of one of her works and has become one of the bywords associated with her—not that it’s ever that simple. The destruction always involves, for her, a corresponding reconstruction: work I have been doing for years in trying to recognize that my father is not simply Father, patriarchal representative, but also a fallible human being. This work is interrupted at moments by dreams like last night’s, but it never ceases.

For years I’ve admired the wonderful passage in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse where James, the youngest Ramsay son, realizes his father is not to blame for his own tyranny; that the tyranny, in fact, comes from elsewhere and uses his father as its instrument. It is in the third and final section of the novel, where Mr. Ramsay, who ten years before insisted the weather would be bad and dashed his six-year-old son James’s hopes of a trip to the lighthouse the next day, now insists on taking James and his youngest daughter, Cam, on the long-postponed boat ride. Both children alternate between fury at their father and near-abject love of him. The novel itself is about achieving balance between opposing feelings and elements; it deals in destruction (World War I and numerous deaths wreak havoc in Part II) and in reconstruction. Here is James, resenting his father at one moment, then realizing his father’s innocence:

He had always kept this old symbol of taking a knife and striking his father to the heart. Only now, as he grew older, and sat staring at his father in an impotent rage, it was not him, that old man reading, whom he wanted to kill, but it was the thing that descended on him—without his knowing it, perhaps tyranny, despotism, he called it—making people do what they did not want to do, cutting off their right to speak. And then the next moment, there he sat reading his book.

Turning back among the many leaves which the past had folded in him, peering into the heart of that forest he sought an image to round off his feeling in a concrete shape. Suppose that as a child he had seen a waggon crush ignorantly and innocently, someone’s foot? Suppose he had seen the foot first, in the grass, smooth and whole; then the wheel; and now the same foot, purple, crushed. But the wheel was innocent. So now, when his father came striding down the passage knocking them up early in the morning to go to the Lighthouse down it came over his foot. One sat and watched it.

James is making the most important realization any child can about his parent—and at a young age, sixteen, long before most of us have succeeded in destroying the Father in order to recreate for ourselves a human, a more reasonable and enabling, lower-case f father.

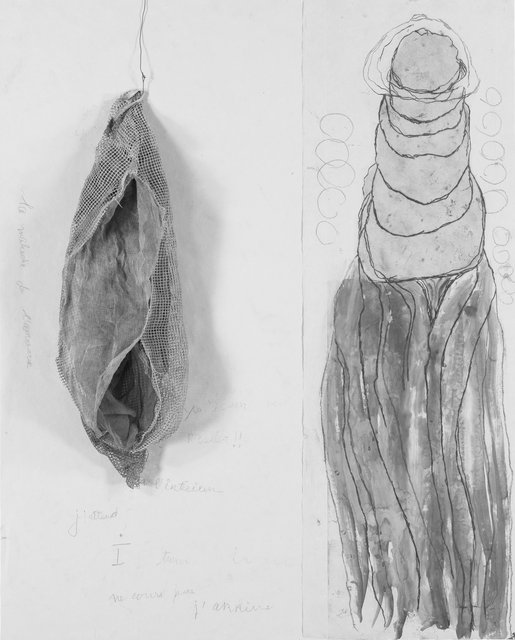

This, Louise Bourgeois does with remarkable fearlessness. She is not afraid to show her desire to take a knife, to cut, to maim, to dismember and castrate. In dismembering, she recreates. Take her remarkable, her adorable Fillette, the famous phallus she is shown, in Robert Mapplethorpe’s photo, carrying under her arm as though it were any object at all, while grinning mischievously at the age of seventy. It is so wonderfully harmless! So decidedly flesh and not symbol—or symbol of flesh-and-not-symbol! It has no power on its own, is merely this sack and this lump, wrinkled, bulgey, and uglily beautiful—just as the wheel in James Ramsay’s metaphor, indeed the wagon, has no power without the system that manufactures all the wagons of patriarchal power. The thing itself is innocent. You could push or carry it down the street like a baby—like a little girl, a “fillette.” The father’s phallus becomes the artist’s daughter.

My father-in-law died last week. I did not love him, I didn’t even like him, but I desired him nonetheless. Not his flesh, which was unattractive, but his assent, his interest, his engagement. I wanted him to be involved with me, to respond. Since he never did, I don’t miss him now that he’s gone. Instead, I am curious, among other things, about Millie, how she will cope, about whether she and I might now be friends. She has softened toward me since the death, though she may well go hard again. Still, I can now hold her, kiss her, utter endearments. Among the Bourgeoisean body parts, I thought of her, her compact little aged body, still quite flexible and spry. (Funny how “spry” is a word always used for the old. It seems to belittle even as it admires their capacity to get around.) I thought of her breasts, which had nurtured my husband, and her womb which had produced him.

Bourgeois never lets us forget where we come from, nor what we desire. More and more I’m struck by the resemblance between adult eros and the parent-child relation. There is nothing elevated about eroticism, though it can feel noble and grand, as it is represented in Romanticism—and Romanticism surely spoke a kind of truth which is not entirely obsolete. In his Diary of a Bad Year, J. M. Coetzee’s crusty elderly narrator reflects on this:

Is it too much to say that the music we call Romantic has an erotic inspiration—that it unceasingly pushes further, tries to enable the listening subject to leave the body behind, to be rapt away (as if harking to birdsong, heavensong), to become a living soul? If this is true, then the erotics of Romantic music could not be more different from the erotics of the present day. In young lovers today one detects not the faintest flicker of that old metaphysical hunger, whose code word for itself was yearning (Sehnsucht).

I hope it isn’t true, though it seems to be. Do my own students, ages eighteen to twenty-two, even listen to, say, Beethoven’s Spring Sonata—in which violin and piano yearn toward each other, sway together, ride lightly one on the other’s back, rise swooningly up through spring leaves toward heaven—and feel what I felt, and still feel now: this is eros distilled, this is the ultimate lovers’ tenderness?

I don’t think we have abandoned Romanticism altogether. Even Bourgeois’s work hasn’t done this; what it has abandoned is that aspect of Romanticism Coetzee designates as bodilessness. Instead of seeking to leave the body behind, these sculptures affirm again and again our emplacement within the body (within the behind, I’m tempted to pun), the fact that even our metaphysical longings arise from the body. (Of course, there is a difference, pace Lessing, or was it Ruskin, between sculpture and music. Nonetheless . . .) Like infants’, our yearnings come down to the breast and the bum. The older I grow, and the less I can romanticize the act of love, the more rooted it seems to me in the oldest needs and wishes. Holding: that comes from infancy. Rocking, sucking, licking; pushing, prodding, spurting and dripping; the curiosity about every body part, the desire to look at and touch even what seems vaguely repellent—all this in middle age, after many monogamous years—feels fundamental in the way all those acts were fundamental in infancy and childhood. Fundament as basis, as arse, as ultimate fact that we are earth-bound—bound to the earth and ultimately, for the earth. Romanticism at times tried to deny this but in its essence, I think, acknowledged it. The movement was inspired, after all, by love of Mother Nature, the ultimate oedipal longing.

Perhaps Bourgeois’s feminist anti-Romanticism resides in her insistence on demonstrating the damage done to our mother by our longing. Longing for her, we have too often tried to tie her down, to make her serve our needs, to render her abject in order to deny the abjection inherent in our own desire. (I have, in the past, hated myself for my desire to touch Millie, to be touched by her—and then hated her so much that I turned her into the classic evil stepmother in a fairy tale.) We have made her seamstress, guardian of fundamental bonds, and we have sewn her up, sewn her closed—sewn her vagina in some cultures, bound her feet in others—bound her down. In the sewn sculptures of her advanced old age, Bourgeois compels us to this recognition time and again. Romantic transcendence has never been an option for woman, sewn and sewer (pun intended) of men’s desires.

And so this work embraces what Simone de Beauvoir, so long ago, called woman’s immanence, and the earthiness, even filth that has been attributed to her in her immanence, her condition as sewer. But it reminds the father of his own immanence as well—this is the difference. Phallus: you are flesh, not signifier. Vulva, arse, breasts: you are flesh, contemned, demeaned, despised, and desired. Phallus, vulva: kindly speak to one another! And so they do, or try to, in works as far from Beethoven’s Spring Sonata as one could possibly imagine—and ultimately, as near to it. In the various versions of La Maladie de L’Amour, cock and cunt are juxtaposed without meeting, in a kind of endless dialogue of longing. In The Couple, a man and woman made of steel hang facing one another, only they have no faces, their bodies from the waist up are coiled about with serpentine rings that end in a knob on the head. From those rings, small arms emerge to clutch at each other. In the bronze Janus Fleuri, another hanging work, two smooth knobs emerge from sheaths; the twain cannot meet, except perhaps in the middle where they mutate into vague matter that looks like lava or feces—according to the exhibition text of the Centre Pompidou the “central almost formless element evokes the feminine slit and pubic hair.” That, too. It is a message we encounter again and again: Eros requires the acknowledgment of the abject; if you try to keep yourself smooth, clean, intact, you will never meet the Other, never know each other. “Let us love one another or die.”

I used to shout at my in-laws, if not literally then through conversational gambits and letters asking them their feelings, begging them to attend to mine, to recognize and embrace me as other than them. I enacted with them, perhaps, the inverse of the struggle with my own parents, from whom I needed greater distance and separation (never, I find, truly achievable or entirely desirable). “In-law”: a French theorist would point out immediately that our relation is dictated by the Law of the Father, by patriarchal rules and conventions and thus hardly “natural.” But then, so is that of parents and children. Just because your flesh spawned mine, I am not necessarily more subject to you than to another. “I don’t want to be an extension of my father,” I said to my therapist in our last conversation. I need to create myself separately from him and recreate him as person, not patriarch.

“I do, I undo, I redo,” was Bourgeois’ phrase—or one of them. This work of separation, and for that matter, the work of intimacy, is an endless, tripartite process. It occurs to me that to “do,” “doo-doo,” happens also to be a childhood phrase for defecation, and Freud pointed out long ago that the small child who hasn’t yet been taught to reject his feces is very proud to have produced it and delighted to use it as sculptural material. There is a further affinity, between shitting and childbearing, that may help explain, in psychoanalytic terms, masculine ambivalence toward the womb. Virginia Woolf once wrote a letter to one of her friends—it may have been Roger Fry—in which she described the coiled turds she watched accumulate beneath her in the earth closet with a kind of wonder at her own creation. This queen of aesthetes and only begrudging admirer of James Joyce was by no means immune to the fascination of what her own arse could produce. The earth closet probably helped; in our modern toilets, the turds sink down into a well before we can properly look at them. Here in Germany, however, I have developed a new intimacy with my eliminations, as this country manufactures a toilet with a ledge. If you look down, you see your crap as a sculpture on a little pedestal below you.

And then you go off to the sculpture museum.

It’s too much, all these body parts, I feel at moments in the darkened space, a former royal stable, where Bourgeois’s most sexual works sit awkwardly alongside those of the surrealist photographer Hans Bellmer. My response gives me some idea of how Millie would feel—how she does feel, indeed, when confronted with allusions to the body, emotions, or avant-garde art. Too much to grapple with. Perhaps that explains why she is dealing so well with the death of her husband of fifty-five years. To capitulate to feeling would be too much, so she chooses the other path. I envy her, a little.

At the same time: I love all this so much I can hardly contain myself; I feel mad with desire. I want to lick the pink plaster sculptures with their multiplicities of breasts, I want to squeeze the fabric female dolls. I want to kick them around like balls (footballs, that is) and take them to bed like pillows. I am in a candy shop, the candy shop of the unconscious, and I want to suck and bite and buy, to take home and hoard—although, being a person of excess, I am incapable of hoarding, I eat and drink all of what’s in front of me. No chocolate bar lasts more than a day, the rare plate resists being licked clean.

It isn’t all infantile desire, however, that these works inspire. Desire is mixed with terror, with an awareness of how often animality means vulnerability, or vulnerability mixed with power in strange ways. In the arched spaces of the stable, there are still columns with hooks and rings, where the horses would have been tethered, slightly evocative of a torture chamber. I have always been powerfully attracted to horses and sometimes think I was a mare in a former life, full of power to run and run but subject to the stallion’s wants and to the fine stroking hand of a human owner. I think I was a happy mare, not a beaten one, with a beautiful chestnut behind and a tail as thick as dark water. But even a happy animal can be destroyed and here are too many images of women reduced, hobbled, bound, and overwhelmed. The one that gets me most is the one that makes me think of my grandmother in her later years: a woman made of dark blue felt bound down on a weird black instrument that looks like a folded-up music stand but is, according to the catalog, a prosthesis of some kind. She has a tiny pinkish head with a mouth like a vulva and a fold leading down to it like buttocks; she is armless and legless but monstrously endowed with two nippleless breasts that protrude up and out to either side of her like balloons. She is woman as form and nothing else, and she is crucified. My beloved grandmother, who’d grown very large late in life, could not sit up easily when she’d lain down on her back, but nor could she lie comfortably with her torso propped up; she seemed most comfortable completely prone. Childlike, I sometimes feared it was I who’d done this to her, just as I feared as a little girl that I was the cause of my father’s dizzy spells, which he described as a “shifting in his head,” and of his frequent headaches.

We do, still, perhaps to the very end, look at bodies as children do, with fascination and terror. Looking up from below, we see the part as the whole; Bourgeois captures this in Henriette, her sculpture that consists of a prosthetic wooden leg with a minimal, nearly abstract face at the top. Our parents’ legs are pillars, and their faces peek out somewhere up above; whole sections of body can seem to be missing even as others are unnaturally enlarged. When I rode my father’s shoulders, I saw the top of his head, the tip of his nose, and his feet. We have conceived our gods similarly, at least monotheists have—perhaps our great mistake, to see the Almighty in scary fragments.

There was a certain amount of invoking of that figure, and of Jesus, sadness, and redemption, at the funeral last month. As it happens, twelve people had just been shot dead by a rampaging gunman in my husband’s hometown, so the chapel of the crematorium was in continual use. We had forty-five minutes in between, in a rather shabby, unswept space without a single graven image. I had my arm around Millie, and I held her hand. I think it is the closest I will ever be to her. Though I am a proselytizer for art and the body—I think secrets do damage, beauty is complex, and the more we speak of our mingled feelings at viewing what others make, and are, the better our social life can be—I will not convert that small, contained Englishwoman who shuns discharge. As long as she is kind to me, I will let her be. And if, perhaps, as I suspect or project, it is a relief to her to be alone at last, without the demands of a spousal ego or expectations of wifely care, I respect her for embracing independence in the last years of her life.