WHAT WENT ON?: THE (PRE-)HISTORY OF MOTOWN’S POLITICS AT 45 RPM

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

On October 23, 1961, Motown Records released the single “Greetings (This Is Uncle Sam)” performed by the Valadiers, an all-white, Detroit-based doo-wop group. The slow ballad traded ironically upon Army recruiting slogans as well as love song clichés to tell the story of a young man drafted to fight in the initial US build-up of the Vietnam War. The lyric notes the sacrifice of young men leaving their girls and families behind to fight overseas. The narrator, sung by lead Stuart Avig, says goodbye to his baby and begs Uncle Sam “please don’t take me away,” while the accompanying doo-wop syllables are replaced by background voices repeatedly intoning “Hup, two, three, four.” As the reluctant draftee croons “I don’t wanna go,” a drill sergeant, enacted by bass baritone Jerry Light, barks belittling statements over the final choruses: “Come on boy, we’re gonna make a man outta you,” “What’d ya mean you never heard of K.P?,” “There’s the right way and a wrong way and there’s my way,” and “Your mama’s a long way off, boy. Stop your crying.”[1]

“Greetings” appeared nearly a decade before Motown allowed Marvin Gaye’s protest anthem “What’s Going On” to hit the airwaves on January 20, 1971.[2] This is surprising, given the usual tale of Motown’s politics as popularly reiterated in books, magazines, and liner notes—a story that dramatically locates Motown’s political breakthrough in Gaye’s 1971 artistic triumph. This oft-told tale explains how the company, in a turbulent 1960s political environment that included a war abroad in Vietnam and a war at home in the quest for civil rights, carefully avoided entanglements, lyrical or otherwise, with such controversies to protect its business interests. This self-imposed political silence supposedly reigned until Gaye won the artistic freedom to release “What’s Going On,” a symphonic soul masterpiece addressing a range of social issues from war and civil rights to poverty, drug use, and the environment. Gerald Posner’s book Motown: Music, Money, Sex, and Power offers an especially detailed version of the tale in which Gaye fights corporate censorship and phones Gordy to say “I’m angry . . . I have to protest,” to which Gordy explains that griping musically about Vietnam and police brutality is “taking things too far.” As sole owner of the company, Gordy tells Gaye that he should “stick to what works”—meaning the sexually tinged pop crooning that had won Marvin legions of female fans and earned Motown strong sales with hits such as 1968’s “Heard It through the Grapevine” and 1967’s “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” a duet with Tammi Terrell.[3] Biographer David Ritz similarly reports that Gaye put his career on the line to get “What’s Going On” released, quoting Gaye saying: “They [Motown] didn’t like it, didn’t understand it, and didn’t trust it. . . . . For months they wouldn’t release it. My attitude had to be firm. Basically I said, ‘Put it out or I’ll never record for you again.’ That was my ace in the hole, and I had to play it.”[4]

Certainly scholars have complicated this myth, observing that Gaye’s masterpiece followed on the heels of such politically charged hit singles as the Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion” (May 7, 1970) and Edwin Starr’s “War” (June 9, 1970), which paved the way for Gaye’s effort. Following Gordy’s method, both hits inspired follow-up releases: the Temps’ “Ungena Za Ulimwengu (Unite the World)” (September 15, 1970) and Starr’s “Stop the War Now” (November 18, 1970). To this list of previous politically edged Motown releases must be added “I Should Be Proud” (February 12, 1970) by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, which tells the story of a woman who has been informed that her lover had been killed in Vietnam, as well as the civil rights anthems “Message from a Blackman” (February 12, 1970) by the Spinners, “Come on People” (April 10, 1970) by the Rustix, and “Young, Gifted and Black” (July 23, 1970); three of these releases even predate “Ball of Confusion.” Stretching back into 1969, one would need to add Smokey Robinson’s cover of Dion’s Top 5 hit, “Abraham, Martin, and John” (June 11, 1969), which mourned America’s assassinated civil rights leaders, as well as “Friendship Train” (October 6, 1969), recorded by Gladys Knight and the Pips, which envisions an interracial community.[5]

Suzanne Smith’s 1999 book, Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit, challenges a range of Motown myths in her critique of the company’s conflicted relationship to the city of Detroit.[6] Smith pushes Motown’s involvement with politics back to at least 1963 in her analysis of the company’s release of its first spoken word album—Martin Luther King’s speech for the Detroit Freedom March.[7] Smith further identifies other issue songs in the Motown catalog that predate “What’s Going On.” In June 1966, for example, Motown released Stevie Wonder’s cover of Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and a complete album exploring the urban crisis, Wonder’s Down to Earth, appeared in the same year. Two years later, Gordy’s need for a hit for the Supremes helped create “Love Child,” a message song that warns of premarital sex, unplanned pregnancy, and unwed motherhood. As Smith writes: “With ‘Love Child’, Motown Records transformed one of the central policy concerns of America’s War on Poverty—inner-city unwed mothers—into a profitable musical product.”[8] Yet even these releases offered some protection to the company—Dylan’s original offered “cover” for Wonder’s protest as simply the repetition of a white artist’s expression, and the Supremes’ hit single amounted to intraracial paternalism—a black company aspiring to white values critiquing inner-city black behavior.

A survey of Motown’s discography concerning the Vietnam War, however, pushes the company’s musical politics back even further and challenges the myth that politics was a commercial disadvantage. On the contrary, politics sold records. Motown’s turn to so-called message songs reaches back at least to 1961 and the Valadiers’ “Greetings” and includes dozens of additional songs, many recently made available by Harry Weinger and Motown Universal’s editions of The Complete Motown Singles, in eleven volumes and more than sixty compact discs. This Vietnam-related repertory paints a different picture of early Motown, one a bit less calculating in its racial politics and a little more desperate to score hits, regardless of their content. What in retrospect appears a premeditated and comprehensive strategy may, in fact, be more a result of commercial trial-and-error experiments. Rather than an avoidance of any political association, Motown used the strong feelings connected to real social issues to sell records, to break in lesser-known artists, and to take advantage of another record company’s success. Motown mitigated the risk of transgressing sensitive topics in at least three ways: by using humor, first introducing them in songs by white artists, and embedding controversy within love songs that softened and individualized any critique.

That Motown releases intersected real-life social themes should not be surprising. Motown founder Berry Gordy’s songwriting philosophy includes the proviso that “[a] song should be honest and have a good concept. The performance is important but the song’s got to be sayin’ something.”[9] Thus Gordy links meaning to commercial potential. Certainly Gordy used other tactics, such as answer songs and writing against the grain of cliché, but what helped make songs like “Money” and “Shop Around” successful was their connection to the listener’s day-to-day experience through this emphasis on meaning. Given such a philosophy, one would expect that the real world and its politics would necessarily infiltrate Gordy’s songwriting. “Greetings” is just such a case. In essence, it is the tale of a young man who receives a draft notice, just as Gordy himself had. Although written by the Valadiers and produced by Motown’s Robert Bateman and Brian Holland, the song parallels Gordy’s own experience in the Korean War. In his autobiography, Gordy writes of receiving a letter from the government: “It started with ‘Greetings’ and ended with ‘Please report to Fort Custer.’ I had been drafted.”[10] According to lead singer Avig, Gordy had asked the Valadiers to write a song that connected with contemporary events, but neither suggested nor objected to the political subtext of the result.[11] The Valadiers, who were just graduating from high school when they signed to Motown, wrote out of their own experience and concerns about the military draft.[12]

Affirming Gordy’s “sayin’ something” philosophy, “Greetings” reached number eighty-nine on the pop chart—a significant accomplishment for the fledgling independent company. Hoping to capitalize on the Valadiers’ success, Motown soon released a follow-up, “Please Mr. Kennedy (I Don’t Wanna Go),” by Motown’s first white solo singer—Mickey Woods.[13] After a military style roll-off, Woods sings the tale of a boy begging to delay his service in order to marry his sweetheart, “Peggy Sue,” lest she fall for someone else while he is away—as the chorus explains, “I don’t wanna go, don’t make me go, ’til she says I do.” Written by Gordy with his sister Loucye, the song features a would-be soldier who claims to “love his country” and “will fight to the very end.”[14] The Valadiers provide backing vocals. Unfortunately, Gordy’s autobiography is silent on his personal feelings about the Vietnam War, yet Motown’s two draft-related songs from 1961 reveal that, if nothing else, he sensed financial opportunity in a potential audience worried about the draft.

It seems strategic that these initial Motown critiques of the draft were recorded by white artists, thus circumnavigating any anger that might be provoked by associating black voices with sounds of social protest. However, in December of that same year, Motown recorded “Your Heart Belongs to Me” on the Supremes, featuring the voice of Diana Ross on lead. Over a rolling Caribbean groove produced by Smokey Robinson and featuring bongos (musical details that further suggest the African diaspora), Ross sings: Lover of mine gone to a faraway land / serving your country on some faraway sand / If you should get lonely / remember that your heart belongs to me. Far from inciting backlash, the song propelled the Supremes’ career, becoming their first single to break into the Top 100 (peaking at Pop number ninety-five in 1962).[15] Again there was little risk of provoking anger as the lyric affirmed the devotion of its protagonist to her patriotic soldier; no hint of concern for his safety surfaces, only a call for him to be faithful.

Recorded by another black artist, Marvin Gaye, “Soldier’s Plea” (April 23, 1962) told a similar story from the perspective of a male soldier: “While I’m away darling I hope you’ll think of me / Remember I’m over here fighting to keep us free. / Just be my little girl and always be true, / and I’ll be a faithful soldier boy to you.” A backing snare drum offers the clichéd military roll-off to begin the song and adds a staccato marching pulse behind the entire song. Gaye himself had served in the US Air Force for a single unhappy year before being discharged.[16] Sometimes referred to as an answer song to “Your Heart Belongs to Me,” Gaye’s “Plea” is more accurately connected to “Soldier Boy,” the Shirelles’ number one hit on the Billboard Hot 100 at the time of Gaye’s release. Similar to the Supremes’ single, the Shirelles’ midtempo ballad offers a promise of faithfulness from a girl to her soldier love: “Soldier Boy, / Oh my little Soldier Boy, / I’ll be true to you. / You were my first love, / And you’ll be my last love.” Musical details link the Shirelles’ song closely with Gaye’s answer: both share the “soldier boy” lyric as well as an extended instrumental solo accompanied by Hammond organ. Within the context of a love song, the Vietnam topos is personalized; the lyrics call not for protest but for faithfulness to love and country.

International relations outside of the Vietnam conflict also appeared in Motown’s catalog. Texans Adrian McClish and Reuben Noel were white Korean War veterans who signed with Motown as the Chuck-a-Lucks and released “Sugar Cane Curtain” in February 1963. Although its title is more typically a reference to the hostile relationship between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the song instead attacks Fidel Castro and the 1959 Cuban Revolution, which brought the “bearded ones” (as the lyrics refer to Castro and his followers) to power. Cuba was still very much a contemporary concern in the early sixties because of the Cuban Missile Crisis (October–December 1962). The bongo crack-and-roll accompanied by flamenco guitar stylings and a lilting bolero feel evoke a Cuban soundscape within a mishmash of Latin and Tex-Mex musical references.

Similarly, Motown’s March 1963 comedy release “The Interview” by Bert “Jack” Haney and Bruce “Nikiter” Armstrong, performing in the guise of John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev, was Gordy’s attempt to capitalize on so-called break-in records in which snippets of popular songs were spliced into a topical comic routine.[17] The unexpected 1956 success of “The Flying Saucer” by Bill Buchanan and Dickie Goodman, which hit number three on Billboard’s charts, inspired similar novelties, which often took on an increasingly political edge. This Motown release on the Mel-o-dy label purports to be an interview of Krushchev by Kennedy in which answers break-in through distinctive lyrics sampled from popular songs:

Q: Nikiter, since the Cuban crisis just how much of the country do you think you’ll end up with?

A: This land is my land from California to the New York Island (from Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land”).

Education was another social issue which Motown found it advantageous to address. In 1963 Motown made the first of several public service announcements in support of education, telling kids “Don’t Drop Out” and releasing the single “Back to School Again” (August 23, 1963), an uptempo dance hymn to the end of summer performed by the Morrocco Muzik Makers from Dayton, Ohio.[18] Rapidfire bongo work energizes the entire song, while saxes recall the Makers rhythm and blues roots. The lyrics send a positive message about returning to school: “Summer’s almost at an end. / It’s back to your pencil and pen, / Because you’re on your way, / Back to school again.” Songs and promos supporting education became a regular effort at Motown with Martha and the Vandellas’ “Back to School” promo, and later Brenda Holloway’s “Play It Cool, Stay in School” (August 1966).[19] In 1965, The Supremes had even recorded Phil Spector’s song “Things Are Changing” as part of a US federal government project—a pop music propaganda campaign “aimed at convincing American youths that employment opportunities in big business are now open to them.” Targeting African Americans in particular, the Plans for Progress initiative that spearheaded the project linked American business with the Equal Employment Opportunities Committee established by President Lyndon Johnson as a result of 1964’s Civil Rights Act. Over a rolling rock’n’roll beat clearly recorded outside Hitsville, Ross implores: “There was a time when the world was fickle and it may have been hard to succeed. But times have changed now and school and training is all you really need,” which ushers in the full trio: “It doesn’t matter who you may be, everyone’s equal with the same opportunity.”[20]

The Civil Rights Movement also presented Motown with commercial opportunities well before 1970. In September 1962, Gordy’s sister Esther Gordy Edwards, who booked the Motortown Revues and would later become vice president and CEO, contacted the Southern Christian Leadership Conference about recording Martin Luther King, Jr. Ms. Gordy, who had received her undergraduate degree from Howard University, probably knew well King’s efforts advocating civil rights, although at this time King remained both too little known and too radical a figure for Motown’s racially integrated target audience. After King’s June 1963 speech for the Detroit Freedom March, Berry Gordy himself became a supporter. As he writes in his autobiography: “Dr. King spoke of how no good could come from hatred or violence. He told me we were all victims. I was a victim and he was a victim, but white people were victims, too, when they allowed their hatred to propel them to act in the ways that some did. He understood it was coming from ignorance, fear and insecurity so he didn’t hate them.”[21]

Such a message supported Motown’s integrated music strategy, and the company released a commemorative gatefold LP of the Detroit speech titled The Great March to Freedom.[22] Gordy’s interest in the album appears to be both personal and sincere; he went so far as to travel personally to a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) benefit in Atlanta in August 1963 to present a personal copy of the album to King. Although Gordy himself does not appear in photos on the album cover, the fact that the company released the album not on Tamla or Motown, but on the label that carried the owner’s personal moniker, “Gordy,” speaks to his commitment to the project. He is also identified on the album label as the album’s producer. The Gordy label was not an attempt to hide Motown’s involvement. The “Motown Record Corp.” is explicitly identified on both the album label and its cover as the corporate umbrella of Gordy’s label. Yet Gordy’s interest was as much financial as political. The release of King’s Detroit speech—which included his soon to be famous “I Have a Dream” oration, anticipated King’s appearance as part of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. By officially releasing King’s album (Gordy 906) on the same day as his appearance in Washington, Motown took maximum commercial advantage of the national publicity accompanying the Washington protest. This strategy succeeded. King’s Detroit speech was only the fourth album released on the Gordy label, but was the first to break into the US album charts, peaking at number 141.[23]

King himself introduced Gordy to gospel singer Liz Lands, who performed alongside such singers as Mahalia Jackson at SCLC events.[24] Shortly after King’s speech in Washington, Motown recorded Lands performing the civil rights anthems “We Shall Overcome” and “Trouble in This Land” at Detroit’s Graystone Ballroom. These were scheduled for release on the Divinity label but never appeared. However, after permissions for King’s Washington speech had cleared, Motown released a second spoken-word album titled The Great March on Washington. In addition to speeches by King, Whitney M. Young, A. Philip Randolph, Walter Reuther, and Roy Wilkins, Liz Land’s Detroit recording of “We Shall Overcome” appears, presumably to evoke the singing of the same song by the crowd at the Washington Mall. A 45 single release with the climax of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and Land’s “We Shall Overcome” was also scheduled for release but was shelved. It finally appeared on April 8, 1968, only four days after Martin Luther King’s death, as both a celebration of King’s legacy and a savvy commercial product. Gordy attended King’s funeral, contributing Motown talent to a benefit concert for the Poor People’s March to Freedom held shortly after King’s death; Gordy, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight, and the Temptations also joined the start of the march, alongside other black artists including Sidney Poitier and Sammy Davis, Jr.[25] Later that year, Motown released yet a third LP of King’s speeches, including the sermon “I’ve Been to the Mountain” delivered the night before he died. This release includes a picture of King’s funeral procession.[26]

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy also had a profound effect on Gordy and Motown. Although most biographies suggest that Gordy had few political interests and focused on hit records above all else, he was an admirer of John F. Kennedy, writing in his autobiography:

I was deeply saddened by the death of John Kennedy. I believed him to be an honest man and a good man. I believed him to be a great President who had embraced and created hope for black people in a way that had not been felt in modern times. A feeling of loss and shock hung over everything in those months of late 1963 and early ’64.[27]

In remembrance, Gordy named a son, born in March 1964, Kennedy William Gordy. Motown’s Studio A also responded to Kennedy’s assassination, releasing a single written by Gordy titled “May What He Lived for Live.” This gospel-infused ballad features Hammond B-3 organ with Land’s soaring vocals backed by a full choir and brass colorings.[28]

Remarkably, Gordy sent his promoter, Al Abrams, to Atlantic City the following year to distribute two thousand free copies of Motown’s JFK tribute to delegates at the Democratic National Convention. According to Abrams, Motown was looking for a hit, and fears that Mary Wells would leave the company were coming to fruition. Abrams, a young political junkie, hoped that attendant publicity about the stunt would drive sales, but he also simply wanted to attend the convention himself. Abrams wrote to John Bailey, chairman of the Democratic Party, and made arrangements with his assistant—an aspiring politician named Joe Lieberman (and later the 2000 Democratic nominee for vice president)—to distribute the 45s, soon thereafter delivering a personally addressed copy of the single to every delegate’s hotel. Motown received letters of appreciation from such figures as Harry Truman and Robert F. Kennedy.[29] Yet Gordy, despite his willingness to celebrate Kennedy’s legacy so openly, remained concerned about political repercussions. After the convention Abrams hung a Johnson-Humphrey campaign poster on the wall of his Motown office; noticing the poster one day, Gordy told Abrams to take it down, just in case a distributor visiting the company might disagree with his political views.[30]

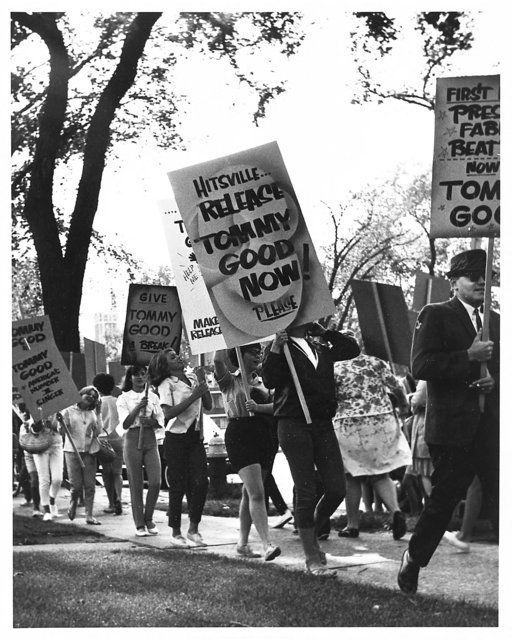

That same summer, Motown was again taking a political risk in search of much-needed publicity. Abrams had earned his job, the first salaried position at the company, through unabashed action. In 1964, he again proposed an audacious stunt—“The March on Hitsville”— trading upon the previous year’s civil rights marches in Detroit and Washington. The summer of 1964 presented a particularly difficult news market with both Detroit papers—the Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press—out on strike; further, Motown had yet to discover a means of successfully promoting its white artists. Abrams’s idea was to bus white suburban kids to Motown’s Hitsville headquarters to stage a mass protest and demand the release of a debut album by Tommy Good, a white, Detroit-born soul singer. Flyers supposedly posted by the Tommy Good Fan Club, but actually posted by Abrams, helped draw protesters to the event. With Good hiding in Abrams’s third-floor office at Motown’s Hitsville headquarters in Detroit, buses arrived and white youth began picketing outside Motown’s offices, carrying signs such as “Hitsville . . . Release Tommy Good Now! Please” and “Give Tommy Good a Break!” According to Abrams’s press release, which was printed almost verbatim in the next issue of Detroit’s Emergency Press paper:

The march caught everyone at the Company completely off guard and succeeded in tying up rush hour traffic over a busy eight block area. There were two minor accidents as homeward bound motorists stopped to look at the unusual spectacle. Said Mr. Gordy of the demonstration, “Reaction like this by a singer’s fans prior to his record release is unprecedented. We expect to have a record out on Tommy Good in the very near future.”

Tommy Good, who still resides in Michigan, explained that he was soon introduced to the crowd and a PA system conveniently appeared, allowing him to perform “Baby I Miss You,” which would indeed become his first Motown single just a few days later.[31]

According to Abrams, Gordy had approved the March on Hitsville stunt, while Esther Gordy opposed it. Berry gave Abrams the go-ahead with the proviso that if the stunt failed, Abrams would be fired. Accordingly, Abrams seems to have wisely downplayed the reverse discrimination angle in both the stunt’s signage and the resulting press release (adding please to a protest sign discourages militancy!). Presumably, the racial politics of the accompanying newspaper photos spoke for themselves.

Abrams frequently leveraged politics for publicity. Before hits were common at Motown, he posed company artists with celebrities, including politicians, as a way to get the singers’ images in front of the public. One example, among many, is a 1965 photo from the Michigan State Fair that shows then-Michigan governor George Romney (father of recent presidential candidate Mitt Romney) posing with the Supremes. That Governor Romney signed this copy for Abrams suggests that such Motown publicity opportunities were seen as positive by white politicians as well. In September 1964, Abrams even went so far as to have Motown extend a speculative recording contract to Luci Baines Johnson, daughter of President Lyndon Johnson, to “record the song of her choice—with proceeds . . . to be donated to the Democratic National Campaign Fund.” Ms. Johnson politely declined the offer.[32] According to Abrams, he knew that Gordy would be against the idea, so he mailed the offer and press release detailing it before Gordy could respond. By the time Gordy’s refusal arrived, Abrams already had received a polite refusal from Liz Carpenter, press secretary for Lady Bird Johnson. Abrams then sent out a second press release announcing that the contract offer had been declined, doubling Motown’s PR boost from the stunt.[33]

By 1966, the conflict in Vietnam had escalated, and anxiety about the draft returned. Sensing renewed opportunity, Motown released a remake of its 1961 draft song “Greetings,” now sung by the Monitors, a black soul group, although it had initially been assigned to the Isley Brothers. The vocal arrangement remains in doo-wop style, even though more recent developments in soul stylings generally and Motown’s signature sound in particular had given doo wop a dated, distinctly 1950s ring. Released as V.I.P. 25032, the single reached number twenty-one on Billboard’s R&B chart and number 100 in its Pop Chart. As lead singer Richard Street explained, “It was our biggest record, because the Vietnam War jumped off. The soldiers and the guys who got drafted loved that song because they did not want to go over there and fight. When we’d sing that in a nightclub, they would just stand up and applaud forever. We went all over the world with that one song.”[34]

However, yet another Vietnam song seems to have preceded this reissue. Singer Martha Reeves had deep personal feelings about the Vietnam War, as her brother Melvin died as a result of his service there.[35] Reeves’s 1964 recording of “Jimmy Mack” was in part a Vietnam protest song. It is well documented that songwriter Lamont Dozier’s inspiration was the death of fellow songwriter Ronnie Mack, who had died of Hodgkin’s disease (not in Vietnam). Yet, Reeves has pointed out that Motown’s paradigmatic “handclaps” for “Jimmy Mack” were created not by hands clapping but by the singers stomping on wooden boards brought into Hitsville’s Studio A. According to Reeves, this effect was intended to evoke soldiers marching and thus offer, not a dance anthem, but a hard-edged song of antiwar protest.[36] So, Jimmy Mack is not just gone, but gone off to war—and he may not be coming back alive. Although first recorded in 1964, Reeves’s “Jimmy Mack” was not released until late 1966 as an LP-only version, and a slightly revised single hit in February 1967, heading quickly up the charts to number one R&B and number ten Pop.

The following year, Reeves sang lead on “Forget Me Not,” a song written by Sylvia Moy, whose own brother had been sent to Vietnam. “I was so upset,” Moy has said, “I wanted my brother to come home all right.” The lyrics begin: “Now we kiss goodbye; you’ll be off to war, the battle’s on I don’t wanna cry as I stand and watch your ship sail on.” While the track’s opening bugle call, played by Harmon-muted trumpets with snare accompaniment and saxophone drone, evoke a military context, the quoted tune speaks intertextually on two levels. First, the bugle tune is in fact a quotation of the Irish tune “The Girl I Left behind Me,” popularized during the American Civil War. It thus recalls both military conflict generally and, potentially, the long struggle for African American rights. Secondly, the tune’s lyrics—unsung on the track but echoing in the memories of some listeners—speak to the same tale of lovers separated by war. This theme of love threatened, intensified, or lost through separation was common at Motown during this period, suggesting that other Motown songs might have implicit or indirect war associations. Likely titles include “I Can’t Give Back the Love I Feel for You,” “The End of Our Road,” “I’ll Say Forever My Love,” and “I Promise to Wait My Love.” And Brenda Holloway’s 1967 “Til Johnny Comes” suggests it may be an answer to the Civil War’s “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.”[37] These songs have no direct military connections in sound or lyric, but tap into the affect of loss by separation. Even Motown classics, such as “Heard It through the Grapevine,” take on added meanings in the context of Vietnam: why the song’s protagonist was away and thus had to hear news of his lover’s faithlessness “through the grapevine” is never explained in the lyric, but it may have seemed obvious to many serving in Vietnam.

Maybe the most remarkable Motown message song released prior to Gaye’s anthem is “Does Your Mama Know about Me?,” recorded only a few months after Detroit’s July 1967 riots by one of Motown’s rare mixed-race ensembles—Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers (February 27, 1968).[38] The 1967 movie Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, about interracial marriage, may have encouraged Gordy to release this ballad on the same topic, but the song is based on the experiences of the group’s Chinese Canadian guitarist, Tommy Chong, and his African American wife. The song explores the issue of interracial love and the probable disapproval of family and friends: “Does your mama know about me? / Does she know just what I am? / Will she turn her back on me /Or accept me as a man? / And what about your dad, did you think of what he’ll say? / Will he be understanding / Or does he think the usual way?” Sung by a soul-tinged mixed-race Taylor, the slow, organ-infused ballad, saturated with a lush string arrangement and orchestral colorings (bells, oboe, and horns), uses the sonic codes of love songs and the sophistication of classical music to validate the integrity of the love discussed in the lyric. Taylor avoids rhythm-and-blues stylings and minimizes the grain in his voice in favor of intimate crooning with a rapid vibrato that signals mainstream sophistication. Increases in volume—into the title phrase and especially the bridge—suggest true passion. The bridge lyric is remarkable for its determination to make the socially discouraged relationship work: “We’ve got to stand tall / Can’t stumble or fall / We’ve got to be strong / For love that’s so right can’t be wrong.” Fierce, percussive exclamations on the drum set during this lyric suggest a resolve to fight for this love.

On the one-year anniversary of Detroit’s July 1967 race riot, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles (all Detroit natives) released “I Care about Detroit” as a special, local-radio-station-only public service release on the Standard Groove label. Detroit was still reeling: just three months before, King had been assassinated. (Ironically, Gordy had already all but officially moved his focus of operations to Los Angeles.) After a long spoken introduction, Smokey’s falsetto melts into the chorus: “I care about Detroit. Yes, I’m proud to call this city my hometown. It’s been good to you and me, so let’s learn to live and work in harmony. Yes, I care about Detroit.”[39]

Motown’s most aggressive civil rights anthem is all but forgotten today. “I Comma Zimba Zio (Here I Stand the Mighty One)” is a black nationalist A-side and part of Motown’s only release by Joseph McLean, a follower of Elijah Muhammad, who had changed his name to Abdullah. Attempting to evoke an African soundscape, the often musically incongruous track begins with mixed percussion and the singer intoning what are apparently Zulu cries. Switching to English, Abdullah sings “I come from the land of the Zulu . . . I’m a beautiful Zulu. . . . Fighting and dying fighing for my Africa . . . living and giving for my Africa.” Although the lyric is at times a cipher, it is nevertheless a stunning track that likely reflects Gordy’s distance from Detroit’s Studio A, both conceptually and physically. According to Raynoma Gordy Singleton’s autobiography, Abdullah had signed with Motown because it was a black company and was stunned to find a white vice president, Ralph Seltzer, in charge of operations in Detroit. Their relationship deteriorated quickly, and after a violent confrontation Abdullah returned to New York.[40]

Motown’s hardest hitting political releases were relegated to the Black Forum label founded in 1970, after race riots (primarily in 1967 and 1968) and assassinations (King, John F. and Robert Kennedy, Malcolm X) had rocked America, but still before the release of Gaye’s “What’s Going On.” Produced by Motown Vice President Junius Griffin, a celebrated journalist and former speechwriter for Martin Luther King, Jr., Black Forum LPs from the first issues proclaim their identity as a “Trademark [of the] Motown Record Corporation.” Rather than an attempt to hide the black company’s involvement, Black Forum’s record jackets proudly lay claim to Motown’s contribution to civil rights:

Black Forum is a medium for the presentation of ideas and voices of the worldwide struggle of Black people to create a new era. Black Forum also serves to provide authentic materials for use in schools and colleges and for the home study of Black history and culture. Black Forum is a permanent record of the sound of struggle and the sound of the new era.[41]

All told there were eight Black Forum LPs released between October 1970 and April 1973. These included speeches, interviews, poetry, and music by activists such as King, Black Panther Stokely Carmichael, Ossie Davis, Bill Cosby, journalist Wallace Terry, poets Langston Hughes and Margaret Danner, and musicians including Elaine Brown, Amiri Baraka, and others. Black Forum’s first release, a King speech titled “Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam,” gained attention for the label immediately by winning the Grammy for Best Spoken Word Recording.[42]

This survey of Motown’s largely forgotten 1961–70 catalog of message songs and LPs contradicts the myth that Berry Gordy’s concerns about an economic backlash silenced Motown’s voice of social consciousness. In fact, Motown released dozens of such songs in the decade before the singles “Ball of Confusion,” “War,” and “What’s Going On.” Yet, Marvin Gaye’s claim that Gordy carefully controlled and shaped Motown’s output and image is also affirmed by this survey. Motown’s political voice steered clear of controversy, taking on potent topics, but those to which its target audience—mainstream, integrated, middle-class record buyers—had previously been introduced and seemed generally in agreement about. Motown criticized the military draft in 1961 (before it had been used in the Vietnam War) and again in 1966, but only after its use had increased and public sentiment had turned against the war.

Motown also used lesser-known artists or those early in their careers to address protest topics, potentially leveraging strong social sentiment as a substitute for notoriety in hopes of driving sales and breaking a group into public awareness. As Motown groups became increasingly successful commercially, their releases avoid making obvious political statements. Thus, The Supremes sing “Lover of Mine” and Gaye records “Soldier’s Plea”—songs of love interrupted by the Vietnam war—early in their careers and at a time when other artists, such as Mary Wells, Smokey Robinson, the Marvelettes, the Miracles, and Martha and the Vandellas, were Motown’s more valuable commodities. Similarly, Martha Reeves had to stomp her Vietnam protest surreptitiously in the hit “Jimmy Mack,” unable to take on the topic directly until 1968 with “Forget Me Not.” By that time, Reeves had been eclipsed by Diana Ross, and thus the potential commercial advantage of protest outweighed any threat to the artist or company.

Love lyrics mitigated the commercial risk of social comment. Love was not only a pop lyric cliché, and thus less threatening, but it also humanized and camouflaged Motown’s political potential in a soft social critique. Songs about the draft, the Vietnam War, and even racial harmony up through 1967 are typically veiled in tales of heterosexual love and thus more likely to be received by listeners within the sphere of their own assumptions—about both love and patriotism. Such universal lyrics also broaden a song’s potential connection with listeners, and thus songs like “Does Your Mama Know about Me?” could be inflected by a range of difference outside of race: religious difference, economic difference, age, class, geography, et cetera. Taylor’s ballad thus is not necessarily a song about interracial love, especially when heard on radio removed from the context of its performers. With few exceptions (e.g., the Miracles with Claudette Rogers Robinson until 1964, and Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers), Motown vocal groups presented a homogeneous racial and gender profile that avoided calling attention to social boundaries. Further, Motown’s white artists frequently introduced potentially controversial topics—such as the draft, US relations with Cuba, or interracial love—thus insulating the company against racially slanted backlash. Humor also mitigated potential offense, helping to moderate political rhetoric, concerning Cuba, for example, for any who might object.

Finally, Motown’s political releases were commercial products. Motown took advantage of occasions of national importance, such as 1963’s March on Washington, to make money and further enhance its brand reputation among specific constituencies. Similarly, Motown’s musical eulogy to President John F. Kennedy, “May What He Lived for Live,” was distributed to thousands of politicians and thus affirmed black support for the Democratic Party and its legislative agenda that had included the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The issue is not so much what motivated Gordy’s or Motown’s interests, but that the company leveraged synergies between commerce and social change, helping to build a more integrated society by creating a market for integrated music.

Acknowledging Motown’s long history of socially potent releases reconfigures our understanding of the work of Marvin Gaye and others at the company. Motown’s political songs of the early 1970s, such as “War,” “Ball of Confusion,” and “What’s Going On,” represent a predictable result of trends within the company and of changes in its social and thus commercial milieu that had developed over the previous decade. An especially powerful statement with percussive punches and a snarling baritone saxophone, Edwin Starr’s “War” aggressively attacks a broadly unpopular war, long after popular sentiment had turned against the conflict. Starr’s pacifist screed was released in June 1970, nearly a year after Jimi Hendrix had performed “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Woodstock. Nevertheless, writer and producer Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong first recorded “War” with the Temptations, a track released on March 7, 1970, on the album Psychedelic Shack, but never as a single. For the single, Motown management chose Starr, an artist recently acquired in the buy-out of Golden World/Ric Tic Records, to avoid further commercial risk for the Temptations.[43] Starr’s performance rocketed the track to three weeks atop of the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

Despite its legend, Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” was not a radical break for the company. Gaye built upon successful formulas in use at Motown for as long as a decade. Like “Greetings” (1961) it addresses the Vietnam War, and, in fact, draws inspiration from the war experience of a close relative—Gaye’s brother Frankie. In this regard, Gaye’s work recalls Reeves’s use of “Jimmy Mack” as well as her single “Forget Me Not,” both responses to the experiences of brothers in the war. Gaye’s sonic protest is also blunted by its breadth. While “War” attacks one specific social issue, Gaye’s song addresses not only Vietnam, but also his own troubled relationship with his family, particularly the father who would fatally shoot the singer in 1984. Gaye’s follow-up concept album, What’s Going On, released four months later, broadened the social messages further to include race relations, drug abuse, poverty, taxes, generational tension, environmental pollution, children, and religion. In this sense, the political impact of What’s Going On (both song and album), like “Ball of Confusion,” is diffuse, as the songs lack a single political focus and reflect a pervasive anxiety in America following the upheaval of the 1960s about the direction of the nation and its potential to heal. Gaye’s masterpiece is not about race, war, drugs, or the environment, but about all those things, and thus is not a sharp, single-edged offensive weapon. “What’s Going On,” is a question posed as statement. It is a moralizing sermon rather than a list of demands. Gaye’s multitracked vocals, pioneering at the time, evoke an other-worldly luxe-pop spirituality, further enhanced by the choral vocalise and lush, legato string melody. Although its commercial success may have surprised Gordy, even here “What’s Going On” was not the first, but the third Motown message track to hit number one on the pop chart, preceded by both “War” and “Love Child.”

As a black-owned company founded in an only recently desegregated and still openly racist America, Motown Records Corporation was always already political. Berry Gordy deftly managed a racially biased business climate through such strategies as hiring white employees to navigate a white-dominated distribution network, using abstract geometric illustrations on his early album covers to hide the faces, and thus the race, of his artists, and selecting a Jewish-sounding name for his publishing affiliate, Stein & Van Stock. Yet the story of Motown’s political silence has been greatly exaggerated. Gordy was a vigilant businessman, and Motown’s cultural activism was carefully controlled. Yet Motown’s activism was never far away and was both commercially viable and socially potent. For Motown, politics could sell and did, beginning as early as 1961. To the question, “What went on at Motown?”; the answer must be—a lot.

NOTES

“Greetings (This Is Uncle Sam)” disc 6, track 3 in The Complete Motown Singles Vol. 1: 1959–1961 (Motown Records, 2004), 68–69. The song was originally released as Miracle 06A on October 23, 1961. Unfortunately this track exhibits serious intonation problems that suggest failed studio manipulations. “K.P.” is military slang for “Kitchen Patrol,” or kitchen duty.

Gaye’s single appeared in advance of the album as Tamla T 54201 A (see The Complete Motown Singles [hereafter abbreviated TCMS] Vol. 11A: 1971 [Motown Records, 2008], 31–32).

Gerald Posner, Motown: Music, Money, Sex, and Power (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2005), 252–54.

David Ritz, Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984; reprint Da Capo Press, 1991), 147–48. Gaye’s quote also makes it clear that Gordy objected to Gaye’s song because of its nonstandard pop format.

Unless noted, release information is taken from the corresponding volume of TCMS.

Suzanne Smith, Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999).

Berry Gordy, To Be Loved: The Music, the Magic, the Memories of Motown (New York: Warner Books, 1994), 85.

Stuart Avig, phone interview with the author, July 25, 2010.

Stuart Avig reports that melodies and lyrics of “Greetings” were written specifically for a Motown session at Hitsville’s Studio A by the four members of the group alone. Bateman and Holland along with Ronald Dunbar share credit, according to the accompanying text of TCMS Vol. 1: 1959–1961, 68. Avig recalls positive responses to the song from friends and fans alike. Ironically, Avig and his brother were among the first soldiers to actually be drafted in 1964 (July 25, 2010 interview).

See TCMS Vol. 1: 1959–1961 disc 6, track 17, released as Tamla 54052 A in December 1961. A brief history of the song appears on p. 74.

Although it’s unlikely that Berry and Loucye knew it, the tale described in “Please Mr. Kennedy” would have effectively exempted the draftee from service, as President Kennedy had directed that married men with children would be placed at the end of any conscription list, with childless married men just above them.

Recorded in December 1961, the initial release of “Your Heart Belongs to Me” failed to move and was rereleased in a version with a heavy echo effect on Ross’s voice in May 1962. Both versions were written and produced by Smokey Robinson, but only the second release broke into the charts. (See TCMS Vol. 2: 1962, 31–32). This record was The Supremes’ last as a quartet; Barbara Martin left the group after this session to start a family.

TCMS Vol. 3: 1963, 58–59; this track should not be confused with another song with the same title by the Four Tops recorded in 1982 for the movie Grease 2.

Information about the publication of King’s recordings is found in Smith, chapter 1 as described above and Brian Ward, Just My Soul Responding: Rhythm and Blues, Black Consciousness, and Race Relations (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 272–74. Fifteen items of correspondence concerning King’s releases are held in Series 6 of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference Organizational Records in the Morehouse College Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection at the Robert W. Woodruff Library of the Atlanta University Center. These items are not yet available to researchers.

Release and chart information on Gordy 906 is from David Edwards and Mike Callahan’s online Motown discography through Both Sides Now Publications at http://www.bsnpubs.com/motown/gordy.html.

Gordy, To Be Loved, 250–251; Smith, Dancing in the Street, 215–18.

The LP is titled: . . . free at last: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Gordy 929), 1968. Each of these three albums would be reissued in the 1980s in connection with Stevie Wonder’s successful campaign to have King’s birthday declared a national holiday. Motown also released a fourth King album in 1970; see below in discussion of Motown’s Black Forum label.

Side B included an up-tempo, Caribbean-infused version of the spiritual “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,” possibly reassuring listeners that hope remained even after Kennedy’s untimely death.

Abrams thanked Lieberman for his assistance by mentioning the future politician by name in each of Motown’s resulting press releases; unfortunately, the publicity stunt occurred in the midst of Detroit newspaper strike and received limited media attention. A book by Abrams, including his complete press releases, is scheduled to be published in 2011 as Hype & Soul: Behind the Scenes at Motown by Soulvation in the UK.

Phone interview with author and Tommy Good, February 4, 2010.

From Billboard clipping in the Alan Abrams Collection, Bentley Historical Collection, University of Michigan.

TCMS Vol. 6: 1966, 26. Inexplicably, the track in this rerecorded release continues to exhibit intonation problems with the accompanying voices as well as the solo guitar going flat.

Reeves’s brother was not killed in action, but rather was wounded, eventually returning to the States addicted to painkillers, which led to his demise (Clague interview with Reeves, February 6, 2010).

Raynoma Gordy Singleton, The Untold Story: Berry, Me, and Motown (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1990), 180–82.

Quote taken from the back of Black Forum’s first release Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam” (BF451, 1970).