THE EROTIC GROTESQUE NONSENSE OF SUPERFLAT: “HAPPINESS” AS PATHOLOGY IN JAPAN TODAY

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The Mori Art Museum occupies the top five floors of the fifty-four-story Mori Tower at the center of Roppongi Hills, a mammoth steel and glass complex in central Tokyo that opened in 2003 as an integrated space for “artelligent living,” working, playing, and shopping (Figure 1). A section of the spacious museum serves as an observation deck where daily hundreds of local and international visitors survey the cluttered and chaotic city spread out 258 meters below. According to the public relations brochure, the Mori Art Museum provides a “dynamic interface between the contemporary art and culture of our times” and serves as broad a public as possible.[1] Seven hundred thousand visitors attended the first three months alone of the inaugural exhibition, “Happiness: A Survival Guide for Art and Life” (October 2003–January 2004). This exhibition serves both as catalyst and foil for my ruminations on the status of happiness and history, two popular and controversial subjects in Japan today.

Magical Timelines

Mori Yoshiko, who chairs the museum’s board (and is married to Mori Minoru, the influential developer of Roppongi Hills), describes the “Happiness” show as

a look at the many diverse ways in which artists have expressed ideas of happiness over the past two millennia. At times it has seemed like a universal human right, at others it has been an intensely personal even private moment.

Now, at a time of war and international instability, happiness and the positive ideas it expresses seem to have a particular importance.[2]

“Happiness” was given expression by 127 international artists and dozens of anonymously produced ritual objects spanning two thousand years of global history. The then-director of the museum, Briton David Elliot, rationalized the deployment of “happiness” as the starting point of an inaugural exhibition: a discussion about happiness, he suggested, is “long overdue”—two thousand years overdue.[3] Elliot and co-curator Pier Luigi Tazzi invoke a nostalgia for a (thoroughly fictional) ancient time when the world presumably was infused with happiness by declaring that the Mori Art Museum show was “part of the redrawing of a circle that has somehow been broken.”[4] The itinerary, or “survival guide” in Elliot’s words, for the show describes it as a journey across four “continents” of happiness—Arcadia, Nirvana, Desire, and Harmony—that represent and recreate an ur-terrestial bliss.

What the “Happiness” show aimed to achieve “in this time of war and instability” was not a proactive engagement with the social, psychological, economic, political circumstances of war and global instability. Rather, the curators sought to transcend the discomfort—and inconvenience—of having to think about such disturbing and traumatic subjects, especially in the oasis of conspicuous and luxurious consumption that is Roppongi Hills. Happiness, it seems, means never having to think about the unhappy subjects of war and global instability—and since war and instability have prevailed for more than two thousand years on our battered planet, happiness means not having to think about history at all.

The glibly optimistic “Happiness” project epitomizes a relentless presentism, the flattening of time and space as a wholly unironic mode of historical awareness that is pervasive in contemporary Japanese culture, most powerfully expressed in Takashi Murakami’s influential aesthetic of “superflat,” about which more below.[5] To get a handle on the dynamics of this sense of the (a)historical, it might prove most useful to think of the Mori Art Museum’s inaugural exhibition as a graphic exercise in constructing a selective (or dehistoricized) chronology. The quirky juxtaposition of nearly two hundred objects produced a novel timeline of global artifacts and events linked by their contributions to the production of “Happiness.” A digression on the magic of timelines must preface my discussion of the “Happiness” show in conjunction with the pervasive aesthetic of superflat.

Most art books and exhibitions in Japan, including the “Happiness” catalogue, include a nenpyō, literally, “year-chart.” The method of making a nenpyō involves the placement of selected events or snippets of historical data to establish, from the perspective of the present moment, a sense of their spatial contiguity and temporal continuity. The timelines appearing in postwar (that is, post-1945) art books and exhibitions more often than not skip over the period 1937–1945, when Japanese artists were recruited by the military state to create pictures that aestheticized the country’s imperialist aggressions.[6] Thus, the wartime productions of many artists, litterateurs, professionals, and intellectuals in general may easily be erased from the bibliographic entries and nenpyō that are included in postwar catalogues and books.

Nenpyō can also serve to create, almost like magic, new genealogies. One way in which timelines achieve this is through erasure. Another way is by juxtaposing things that are otherwise unrelated in time and space in order deliberately to create an illusion of their relatedness. Timelines are, in effect, anachronistic montages. Elsewhere, I have named this magical phenomenon “nenpyōlogy,” a “science” of genealogy-building that displaces, disrupts, and discourages rigorous historical analysis.[7] The magic of nenpyōlogy, that is, the creation of a pervading, dreamlike synchrony, or what I call “relentless presentism,” was given full expression in the Mori Art Museum’s inaugural exhibition.

From Overcoming the Modern to Overcoming History

The entrance to the Mori Art Museum is marked by a giant glass cone nestled against the tower. Inside, a broad spiral staircase leads visitors to a dimly lit ticket lobby from where they take a high-speed elevator to the spacious fifty-third- floor rosy sandstone atrium around which the upper and lower galleries are arranged. I began my “Happiness” journey with an escalator ride from the atrium to the upper-level gallery. On either side to welcome me and my fellow travelers was a giant color photograph of performance artist Morimura Yasumasa in drag as a flamboyantly exotic multiculti goddess.

As I toured the sprawling and eclectic “Happiness” show, it occurred to me that the exhibition was reminiscent of the attempt made in 1942 by a group of Japanese intellectuals to “overcome the modern.” The ahistorical (or dehistoricized) aspect of the show prompted me to create my own conceptual timeline by juxtaposing these two discontiguous events in order to critically analyze the status of happiness and history in Japan today. Let me explain.

In July 1942, at the highpoint of Japanese empire-building in the Pacific, a conference called “Overcoming the Modern” (kindai no chokōku) was convened by prominent scholars and social critics.[8] Japan controlled much of the Asia-Pacific region by that time and it was also at war with the United States and its allies, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In part, the “modern” to be overcome was the ongoing process, begun in the late nineteenth century, of the westernization of Japanese institutional and popular culture. The conferees included philosophers, critics, artists, novelists, and politicians who pondered whether the trajectory of Japan’s modernization could be rerouted by refuting the Euro-American capitalist paradigm. They proposed instead a nostalgia-steeped agenda that reified an autonomous, nationalist, and spiritually pristine conception of Japan’s superior cultural essence. This cultural essence, or “Japanism,” was perceived as something that existed outside of history and that, therefore, was impervious to sociohistorical transformations; it was something that was always already continuously present.

There have been many efforts over the past millennium to reify Japanese cultural essence. Historians of Japan will recall the nativist (kokugaku) movement of the eighteenth century that called for a return to the ancient spirit or essence of Japan as it allegedly existed before the introduction of Buddhism and Confucianism from China via Korea in the sixth century. Nativist ideologues conjured a purely Japanese past based on allegedly indigenous traditions as a way of overcoming the then Chinese-inflected modernity. In the eighteenth century, China was perceived as the usurper of Japanism; in the twentieth century, it was “the West.” More recently, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, some conservative ideologues, foremost among them former Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro, proclaimed that Japan was no longer a postwar country, and that the rubric “postwar” had too many associations with the Allied Occupation of Japan (1945–52). Nakasone’s inauguration of a “post-postwar Japan” was presaged by the compulsory education system: since 1945, the majority of Japanese students have not been exposed in any rigorous way to the country’s wartime history and its ramifications. Only in 1997 did the Ministry of Education[9] approve school textbooks that began to acknowledge—albeit in very watered-down terms—such acts of aggression as the Nanjing massacre, the existence of biological warfare laboratories, and state-sanctioned coerced prostitution (aka the “comfort women” system). However, this admission was short-lived. As reported in the 11 March 2007 Japan Times,

Former education minister Nakayama [Nariaki] takes pride in an achievement he and about 130 fellow members of the Liberal Democratic Party took the past decade to accomplish: getting references to Japan’s wartime sex slaves struck from most authorized history texts for junior high schools. . . . “Our campaign worked, and people outside the government also started raising their voices, creating a national trend,” said [Nakayama], the 63-year-old Lower House member from Miyazaki Prefecture, who also openly claims the 1937 Nanjing Massacre was a “pure fabrication.”[10]

Not to be overlooked as a conscious act of neonativist renewal is the so-called liberal historiography (jiyushugi shikan) of Tokyo University Professor Fujioka Nobukatsu. In the mid-1990s, Fujioka organized a revisionist movement to restore a “correct history” (seishi) of imperial Japan in textbooks. By choosing the term “liberal,” Fujioka and his supporters sought to represent their position as a breakthrough from the stale and unresolved polarities of post-postwar discourse into something fresh and new.[11] However, “liberal” here is simply short for “liberating” without the positive, progressive nuances that term conveys in English. At the core of Fujioka’s message is a view of history centered upon a lament for the loss of a “distinctive Japanese historical consciousness” (Nihon jishin no rekishi ishiki). He takes particularly strong exception to school history texts approved for use in April 1997 that add the “forcible abduction of comfort women” to accounts of the Nanjing massacre and other atrocities committed by the Japanese imperial forces.[12] As former education minister Nakayama has made clear, that exception is now a moot point, for in August 2009, Yokohama was the first large city to authorize for use in public middle schools the nationalistic textbooks produced by the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (Atarashii Rekishi Kyokasho o Tsukuru Kai), cofounded by Fujioka.[13]

If the 1942 roundtable was devoted to the quest of overcoming modernity, the Mori Art Museum’s “Happiness” show was devoted to overcoming history. In this respect, it was similar to Fujioka’s attempt to correct history. One of the most blatant revisionist aspects in the “Happiness” show was the puzzling—and troubling—inclusion of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia I & 2: Festival of the People, Festival of Beauty of 1936–37. Her cinematic homage to the Nazi cult of the idealized Aryan body was included among the Buddhist sculptures making up Arcadia, the “continent” described in the catalogue by David Elliot as “a mythical world of hope and promise that encompasses the possibility of there being a social paradise on earth.” Were the curators and the Museum’s board implying that the Nazi Lebensraum and the Buddhist nirvana were equivalent sources and sites of happiness? Apparently the history-erasing magic of the two-thousand year “Happiness” timeline was powerful enough to overcome even the overwhelmingly overdetermined association of Reifenstahl’s Olympia with nationalist and genocidal policies. And herein lies the danger of willful nostalgia and its corollary, relentless presentism: one cannot remember never to forget if what one is to remember never to forget is expunged from memory.

The notion that happiness means never having to face inconvenient truths is at the core of an increasingly visible and media-savvy new religion (shinkō shūkyō) called Happy Science (Kofuku no Kagaku), founded in 1986 by former corporate trader (and CUNY student) Okawa Ryuho, who is the sect’s CEO.[14] Okawa heads the Happiness Realization Party (Kofuku jitsugento, HRP), a political party established in May 2009 that flouts the constitutional separation of religion and state. His wife Kyoko heads the party’s public relations and advertising office and is the public face of HRP on television and in full-page advertisements in the guise of news articles. The HRP platform endorses a “liberal historiography” and what appears as a kind of state religion, similar in principle to State Shinto and the emperor worship mandated in imperial Japan. Aiming at nothing less than the displacement of the United States as the global superpower, the HRP supports the militarization of Japan in anticipation of a conflict with North Korea and China. Okawa claims to be the most recent incarnation of El Cantare, identified as a supreme god who earlier took the form of Hermes, the Buddha, and several other mythic and historical figures. Okawa boasts of his ability to channel the thoughts of Mohammed, Jesus, and even President Barack Obama.[15] Given his own ersatz genealogy, Okawa would probably approve of my pointing out the similarities between his conflation of Buddhist enlightenment and nationalism, and the juxtaposition of nirvana and Lebensraum in the “Happiness” show.

Takarazuka, Morimura, and Relentless Presentism

Another thought that occurred to me as I made my way through the “Happiness” show was how conceptually similar it was to the renowned all-female Takarazuka Revue—a living timeline, as it were. An excerpt from the Takarazuka’s public relations brochure illustrates my point here:

Foreigners visiting Japan often comment on how difficult it is to understand the Japanese. . . . [Takarazuka] affords both Japanese and foreigners an instant history of an incredibly complex artistic heritage, a window to view Japanese life, dance, music, culture and, what is perhaps most interesting of all, a playback of how the Japanese see and interpret the West. “Takarazuka” is Japan. It is a race through history, a course in theatre and a cultural experience all wrapped up in sparkling sequins and gorgeous costumes. . . . [N]owhere else is there so much to learn and see and enjoy about Japan.[16]

However, the race through history offered by Takarazuka is ahistorical: its version of a national cultural genealogy is a montage of invented and revised traditions. Takarazuka’s Japan is unsullied and uncompromised by the ugly realities and uncomfortable memories of wartime aggression.[17] The Revue is in the business of selling dreams, and with the exception of revues produced at the height of Japanese imperial war-mongering, between 1937 and 1945, the Revue stages only shows that recall a safely distant Japanese past or conjure up glitzy, fantastic visions of exotic lands across the ocean.

Founded in 1913 by Kobayashi Ichizo (1873–1957)—a leading entrepreneur, cabinet minister, and developer of Japanese-style capitalism—the Revue’s sumptuous sets continue to provide audiences with an enticing and accessible vision of capitalism and commodity culture in the guise of entertainment, pleasure, and desire. The Revue is a dramaturgical montage of different, even contradictory, images of foreign lands, exotic settings, diverse peoples, and dreamy scenarios. In the wartime period, the Takarazuka Revue was deployed as a system of cultural artifacts in the service of imperial Japan; it was an important proving ground where a composite image of modern Japan—itself a synthesis of the slogan, “eastern spirit, western technology” (wakon yōsai)—could be crafted, displayed, and naturalized. In keeping with its etymology, the revue theater represents a break from the past. With its fast-paced juxtaposition of fragmentary episodes, the montage-like revue allows for a blossoming of allegories which provide for multiple jumping-off points from which to generalize human experience, such as expressions of “happiness.”

Earlier, I noted that Morimura Yasumasa’s multiculti goddess images welcomed me and other visitors to the “Happiness” show. Morimura is a longtime, avid fan of the Takarazuka Revue. Born in 1951, he is also a product of the postwar educational system. As a young adult, his worldview was influenced more by the antiestablishment, anti-American student movement of the late 1960s than by an interrogation of Japanese militarism and imperialism. I wish to emphasize here the important influence of the Takarazuka Revue on Morimura’s performance art. His connection with the Revue tends to be overlooked by many literary and art critics, who credit him alone with ideas and practices about the mobile and shifting relationship of sex, gender, and sexuality that actually have a very long history in Japanese culture. The Revue is quite central to Morimura’s work in three major ways. One way is the uncoupling of sex (in the sense of a female or male body) from gender (femininity and masculinity).

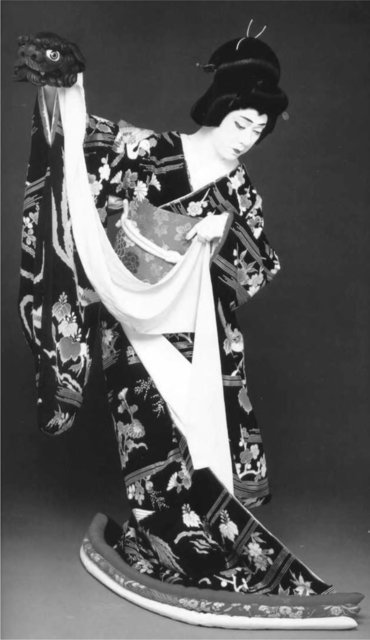

Although most reviewers of Morimura’s work focus on this aspect, it is not what I find to be the most salient feature of his work. The mobile and shifting relationship of sex and gender (and sexuality) has an ancient history in Japan—at least since the first extant mythohistorical texts of the early eighth century—and is not particularly radical or even controversial. Morimura’s model is the otokoyaku (man-role player), a female assigned to perform idealized masculinity on the Takarazuka stage. The musumeyaku (woman-role player), in contrast, is a female assigned to perform an exaggerated femininity that highlights the masculinity of the otokoyaku. The Revue is a pink and blue universe, although it has inspired a “butch-femme” lesbian subcultural style in Japan (figure 2).[18]

The Takarazuka otokoyaku is not the equivalent of the Kabuki onnagata, or femininity specialist, who, especially before the postwar period, metamorphosed (henshin) into a woman. Yoshizawa Ayame, an onnagata who established the theoretical foundation of that role in Ayamegusa (Ayame’s Miscellaneous Writings) in the early eighteenth century, conceived of the onnagata not as “a male acting in a role in which he becomes a ‘woman,’” but rather as “a male who is a ‘woman’ acting a role.” In other words, the transformation is not part of a particular role but precedes it. The onnagata was also regarded as a model of femininity for females to emulate. Otokoyaku, on the other hand, are not to become unequivocally masculine, much less a model for males to emulate (figure 3). Rather, their achievement of manliness is expressed in

terms of “putting something on the body” (mi ni tsukeru), in this case markers of masculinity.[19] Similarly, Morimura does not so much metamorphose into as inhabit the personae of glamorous women—women who themselves inhabit an ideal type, that is, a manufactured and commodified image. Whereas Morimura is similar to the kabuki onnagata in his reproduction of an exemplary feminine form, neither he nor the onnagata impersonate ordinary females.

A second way in which the Revue is central to Morimura’s work is his practice of “cross-ethnicking,” itself a mainstay of the Takarazuka theater, but one with a more controversial

history. In addition to portraying a wide range of men and women, the Takarazuka actors also embody and perform non-Japanese characters of diverse national and ethnic backgrounds. During the 1930s and 1940s, mobile corps of Revue actors performed culturally correct(ed) models of colonial subjects to be emulated by peoples in Asia under Japanese colonial rule. Just as the kabuki onnagata exemplified ideal femininity, so the Revues actors portrayed the proper, that is, Japanese, way to look and act Chinese, Korean, Indonesian, Taiwanese, and so forth. Similarly, Morimura also cross-ethnicks—as Bridgitte Bardot, Marilyn Monroe, and others (figure 4).

A third, and in my view the most disturbing, way in which Morimura’s work is related to the Takarazuka Revue recalls my earlier reference to dramaturgical montage. As illustrated by his exotic goddess impersonations flanking the entrance to the “Happiness” show, Morimura’s work is conceived and produced in the spirit of montage. He poses himself in different guises and settings. In some work he photographically splices or grafts himself into canonical paintings, thus shifting the historical referent of a given painting to the present of Morimura, whose presence flattens the contextualizing time and space of the painting. A good example of this process is his production of Takarazuka Revue’s ninetieth anniversary album, Takarazuka: The Land of Dreams. Morimura produced three images with the same title—The Power to Dream—but different subtitles. I will focus on only one of the images in order to illustrate my point about montage, nenpyology, and the simultaneous erasure and flattening of history together with the invention of a new genealogy.

The Power to Dream: Materialized into History, Erased into

History: The image is a cropped photo-reproduction of the Romanticist painter Eugène Delacroix’s large painting Liberty at the Barricades exhibited at the Paris salon in 1831. Morimura here plays with presence and absence. Delacroix’s figure of Liberty is missing from both of Morimura’s renditions. She is completely missing from the erased version, and in the materialized version (figure 5), she is replaced with the image of Morimura as Oscar, the bisexual, transgendered protagonist of The Rose of Versailles, Takarazuka’s most popular and regularly reprised revue based on the comic book by Ikeda Riyoko. Morimura puts his face on the other figures as well, transforming Delacroix’s homage to the rebellious cross-section of revolutionary French society into a narcissistically self-referential homage. He also positions Oscar—or rather, himself as Oscar—as a stand-in for the missing Liberty, who in Delacroix’s original, wears the red cap of liberty, the emblem of freed slaves. In the revue, Oscar, born as a girl but raised as a boy by her father, lives a luxurious life as a member of the aristocracy in the years before the revolution. Although “he” becomes commander of the palace guards, Oscar is a little troubled by the abject poverty of the lower classes. That said, the only kind of liberty that Oscar represents is liberty from a strict alignment of sex, gender, and sexuality: Oscar at times is masculine and partnered with a masculine male, at times masculine with a feminine female partner, and yet at other times feminine with a masculine male partner. In other words, Oscar occupies many different sexualized and gendered subject positions—liberating, perhaps, but several steps short of Liberty.

Whereas Delacroix’s painting reverberated with the righteous self-determination of the French, both of Morimura’s versions are wholly self-referential. And whereas Delacroix’s painting was displayed only a year (in the Luxembourg Gallery) before being put into storage for fear of inspiring insurrection, dozens of copies of Morimura’s version were available for sale from the outset. In fact, one part of Morimura’s website ([http://www.morimura-ya.com/shop_m/index.html]) is designed as a multistoried department store. (Note, in this connection, that the main theater of Takarazuka Revue was originally conceived as an extension of a railroad terminal department store, and Takarazuka productions showcase the dramaturgy of capitalism with their opulent sets and upmarket splendor.) And whereas, over the past century, Delacroix’s Barricades has become intermingled with personifications of the French Republic and has come to embody the authority of the French state—from 1979 until 1994, the picture appeared on the back of the hundred-franc note—Morimura’s version celebrated the ninetieth anniversary of the Land of Dreams and the ascendancy and dominance in Japan today of, in Morimura’s words, “art as entertainment.”

Morimura has inserted his body into a number of other iconic art works. One of his best-known works is Futago (Twin), his 1988 interpretation of Manet’s Olympia (1863), in which he portrays both the courtesan and her black servant. Morimura here exploits, with the aid of computer technology, photography’s ability to both deceive and duplicate (figure 6). In his observations about Morimura’s cross-dressing perfor-

mances—which he conflates with “cross-ethnicking”—British art historian Norman Bryson suggests that Morimura’s Olympia/Futago

maps the placement of Asian and African bodies in the psychogeography of a world once dominated from the West. Within that map, if the Asian male is the place of imagined phallic lack or deficit, then the black male body is the place of imaginary phallic surplus. What Morimura describes is a fantasy of the body outside Europe organized in terms of pluses and minuses. . . . As in Manet’s “Olympia,” the white figure is placed as “top” and . . . Asian and African bodies assume their preordained compliant positions.[20]

Contrary to Bryson, Morimura actually shies away from cultural critique, and his binarist impulse is also evident in his evocation of European colonial history. Disturbingly, Japanese colonialism is an absent referent. Japan was an anticolonial colonizer and does not fit into the tidy binarist schemes of East versus West, North versus South that tend to characterize critical theories of colonialism premised on a western perspective. What if Morimura had turned Olympia into a Korean comfort woman bearing his Japanese face, and rendered her servant an Imperial Army soldier also bearing his face? Now that would have been an act of embodied cultural critique. But, in the end, Morimura retains an ambivalent, facile, and wholly dehistoricized attitude toward colonial fantasy. He profits—in every sense of the word—handsomely from post-postwar presentism.

As I argued earlier, the boundaries of sex and gender that Morimura is credited with pushing had already been pushed by kabuki and the Takarazuka Revue. Cross-dressing and cross-ethnicking are hardly novel or radical, and Morimura himself stays well within the received paradigm of a Eurocentric postcolonial critique of western colonialism (as described by Bryson). Moreover, cross-dressing and cross-ethnicking reinforce the dualism of oppositionally constructed images of females and males, us and them. For cross-dressing and cross-ethnicking to truly frustrate binary thinking, the element of serious parody (as opposed to playful, self-referential entertainment) must also be mobilized to draw attention to the artifices that uphold the status quo. Androgynes and hybrids can create an illusion of symmetry and in this way conceal the asymmetry of power and its exercise.[21] Likewise, timelines can create an illusion of regularity and thus conceal irregularities and discontinuities. Furthermore, ambiguity and ambivalence can be used strategically in multiple, intersecting discourses, including art, both to contain difference and to reveal the artifice of containment. The creative tension between the containment of difference and the exposure of the artifice of containment—this is precisely what is missing in the realm of superflat where such distinctions are summarily disappeared.

Murakami and Superflat

Nothing in what Morimura has said or done suggests that he conceives of his work either as subversive or as a critical commentary on a range of controversial subjects, from colonialism to sexism. He has successfully exploited the fact that he, and his work, are symptomatic of what I have called relentless presentism, or what the influential artist Murakami Takashi calls “superflat,” the subject to which I now turn.

Murakami designed the cute (kawaii) theme characters for the Roppongi Hills complex, and his work was also featured in the “Happiness” show. Like Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons before him, Murakami emphasizes his affinity—even his identity—with commercialized, commodity-driven popular culture and its glitzy surfaces. And like Warhol and Koons, Murakami also produces his art work in a factory. He employs a staff of sixty who punch in and—this being a Japanese factory—participate in group calisthenics before painting “cute” designs in bright acrylic colors. What Andy Warhol said about himself could easily have come from Murakami’s own mouth: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol [read Murakami Takashi], just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”[22]

It comes as no surprise that Murakami, born in 1963 and a product of the postwar education system, should have developed the aesthetic of superflat. Murakami’s first use of the concept of superflat was in reference to the lack of linear perspective in pre-European-influenced painting, such as that produced by the Kano school in the premodern period. Of course, in setting Japan against Europe, Murakami here neglects to note that linear perspective was one of many representational systems in European painting even before it was explicitly theorized in the sixteenth century. Murakami extended Japanese art historian Tsuji Nobuo’s idea that formal characteristics such as the flat, shallow space and bold linear elements found in nihon-ga, or Japanese-style paintings, are also evident in contemporary art forms, such as manga (cartoons) and anime (animation films). Note too that the term nihon-ga was coined in the Meiji period (1868–1912) to distinguish (and in effect to create) a multimedia art different from European-inspired oil painting, or yōga. And it is common knowledge that even nihon-ga artists have employed linear perspective. Instead of engaging critically in the pathological aspects of superflat, Murakami chooses to implicate himself as part of the pathology of a willfully arbitrary and amnesiac dominant society, and, thereby, to release both himself and his viewers from grappling with the contradictions of Japan’s wartime experience as an anticolonial colonizer. The aesthetic of superflat, in other words, serves as a clever rubric for the willful evacuation

of historical context in Japanese culture and its substitution with “corrected” history and invented traditions.

Unlike Morimura, Murakami does not use himself as a model; rather, he creates his own characters, like DOB, into which he himself is absorbed (figure 7). (DOB is the abbreviation of a nonsensical phrase.) Murakami claims that “DOB is a self-portrait of the Japanese people. He is cute but has no meaning and understands nothing of life, sex, or reality.” Although DOB is referred to as “he” (kare), most of Murakami’s characters are also superflat in the sense that their cuteness supersedes and surpasses any and all sex and gender distinctions. One exception to this is his Hiropon series of “female” sculptures that are anything but flat, in a literal sense. The word has two meanings: it alludes to the popular term for amphetamines in the immediate postwar period, and it means “exploding (pon) hero (hiiro).” The Hiropon characters were first created in 1997 and are an exaggeration of the cute and pretty girls (bishojo) fetishized in the often pedophilic otaku, or media geek, subculture. A typical otaku is male, ranging in age from teens to middle age, infatuated with prepubescent girls and obsessively attached to sweetly erotic comic-book characters and dolls.

Ms. Ko2 (Koko) is a two-meter tall Hiropon who encircles herself with milk squeezed from her gargantuan breasts. Apparently, she was inspired in 1997 by a cartoon Murakami had seen of a woman with phallic nipples. The following year, in 1998, he created a companion piece, My Lonesome Cowboy, whose ejaculate forms a lasso (figures 8 and 9). Milk and semen, female and male, are equated and flattened out as symmetrical entities. The perversely copious body fluids of both Hiropon characters create a self-enclosed, self-contained space, with references to the gashapon toys sold in capsules especially for obsessive-compulsive collectors.[23] The sculptures have caught the fascinated fancy of Euro-American (male) collectors, who have paid six-figure prices for them. Murakami claims that his Hiropon characters are intended not to critique or parody otaku culture but to provide consumers with objects of affection in the spirit of poku, or pop otaku, as a recent show of his was titled.[24] Accordingly, whereas the earliest DOB had sharp teeth, the rotund creature now sports a benign smile.

Ero Guro Nansensu Redux

Ero guro nansensu, “erotic grotesque nonsense” in Japlish,[25] was the mass media catchphrase for the new mass culture in Tokyo that emerged in the years after the devastating 1923 earthquake. It is also an apt characterization of today’s mass-mediated popular culture and its agents. The late, brilliant historian Miriam Silverberg, who wrote extensively on early-twentieth- century mass culture, made a compelling case for broadening the meanings of this phrase. As she explains, ero could connote lasciviousness but also allude “to a variety of sensual gratifications, physical expressiveness, and the affirmation of social intimacy.” Similarly, in addition to “malformed or obscenely criminal,” guro is associated with the “social inequities” of consumer culture. And nansensu goes beyond references to foolishness and slapstick comedy to define the political, ironic humor of modernity.[26] Citing the work of literary theorist Linda Hutcheon (1995), Silverberg notes that irony “happens in the space between the said and the unsaid,” and develops in a “hierarchical setting containing the speaker of the nonsense, the audience, and the excluded—those who are the targets of the humor.”[27]

What is different about the ero guro nansensu of today, as captured by the “Happiness” show, and in the self-referential, self-contained work of Morimura and Murakami, is the utter absence of irony; it is all parody all the time without any ironic distance. There is no “space between” in a superflat world. In his 1995 article, “The Murakami Method,” arts writer Arthur Lubow observes that

the grab-bag appropriation, inexact simulation and accelerated speed that characterize [Murakami’s method] no longer appear peculiarly Japanese. They feel now. We live in an age when distinctions are arbitrary, originality is devalued, hierarchies are discredited and authenticity seems meaningless. . . . We are surrounded today by too many images to source or rank. While it would be fatuous to say that we are all Japanese now, we are surely living in Murakami’s world.[28]

If we all lived in Murakami’s world we would all resemble the toothless DOB. But Lubow has a point. I have always proclaimed to friends and colleagues that if one wanted to know what is coming down the pike, one should look at what is already happening in Japan.[29] Bad loans, survival games, iron chefs, reality shows, virtual friendships, anime avatars, humanoid robot proxies and companions, hybrid cars, posthumanity—all, if not gestated, were nurtured and enhanced in Japan. Take robots, for example. Japan accounts for over half of the world’s share of industrial and operational robots, and leads in the production of humanoid household robots designed to care for children and the expanding ranks of the elderly, to provide companionship, and to perform domestic tasks. Happiness in the form of a robot-dependent society and lifestyle by 2025 that is safe (anzen), comfort-inducing (anshin), and convenient (benri) is the aim of Innovation 25, the government’s visionary blueprint for Japanese society introduced in February 2007.[30]

Based on my interviews over the past several years with roboticists in their labs and at robot-expos, and on the ballooning literature on humanoid household (or partner) robots, I realized that humanoids are regarded by many Japanese as preferable to foreign laborers, and especially to foreign nurses and caretakers. Unlike migrant workers, robots have no cultural differences or historical (or wartime) memories to contend with. In addition to their apparently unsettling “cultural differences,” foreign workers (especially those from Asian countries formerly colonized by Japan) embody and represent memories that, even unintentionally, could agitate ordinary Japanese. As discussed earlier, dominant agents continue to perpetuate the myth of Japan as a homogeneous nation, and to cultivate a willful amnesia with respect to the history of Japanese imperialist aggression in Asia. Robots—and their world—are reassuringly superflat.

Murakami has declared in many interviews that his artwork expresses “hopelessness,” and specifically the hopelessness of post-postwar Japanese.[31] He does not, however, venture any definitions of hopelessness. In Murakami’s world at least, hopelessness has been happily profitable for the artist and his patrons, including the real estate mogul Mori Minoru. As one who is newly hopeful, thanks to a regime change in the United States, I wish to conclude on a polemical note.There is simply too much at stake in the world, for the planet, for people, especially those who command the media limelight, to indulge in the erotic, grotesque, nonsensical antics of hopelessness, detached ambivalence, arrested intellection, convenient platitudes, and perverse notions of “happiness.”

In 1942, a conference was convened in Japan to think about ways of overcoming modernity. In 2003, the “Happiness” exhibition was staged to celebrate a seamless two thousand years of global joy. Over most of the span of the intervening six decades, the government of Japan carried out an annual Opinion Survey of the National Lifestyle among ten thousand respondents that includes direct questions about their level of happiness, which is referred to obliquely as “mental satisfaction” and types of aesthetic “sensitivity.” However, according to Yoshizoe Yasuto, the president of the Japanese Statistics Council, the government remains uncertain as to how and when to apply “happiness” in policymaking.[32] Contrary to Yoshizoe’s claim, since at least 2000, “happiness” has been prioritized as a laudable pursuit by all of the main political parties in Japan. “Happiness for one, happiness for all,” is the refrain of the Liberal Democratic Party’s anthem, “Warera” (We).[33] Newly elected Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio quoted Albert Einstein in his first policy speech to the Diet in October: “We exist for other people first of all, for whose smiles and well-being our own happiness depends.”[34] And, as I noted earlier, the newest political party in Japan calls itself Happiness Realization.

My critique of the “Happiness” show and its analogs past and present focuses on their indulgence in “flat world thinking.” “Liberal” historiography, Morimura’s narcissistic usurpation of historical context, the seductive hopelessness dispensed by the Murakami factory’s cute characters, the deployment of a memory-less robot labor force, and so forth, are at once consequences and agents of the time-and-space flattening forces of relentless presentism. In closing, I am reminded here of the following allegorically apt proclamation in a website on leadership values for the future that I discovered in the course of exploring online the varieties (and critiques) of superflat: “Flat World thinkers are not necessarily interested in new perspectives. They’re interested in the comfort zone and being RIGHT! As a result, they stay stuck.”[35] Perhaps happiness means never having to say we’re stuck.

NOTES

The first incarnation of this article was as a keynote lecture for the postgender exhibition and conference at the Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art, Haifa, Israel, 8–9 December 2005. I would like to thank Celeste Brusati for her insightful comments and Ayelet Zohar for providing the initial impetus and occasion for thinking about the relationships explored here.

1. Mori 2003: 7. Originally, the Mori Art Museum was conceived as an arena of display and only in the past couple of years has it started its own collection. Roppongi Hills, including Mori Tower, was designed by the architectural firm of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates, and the museum by Gluckman Mayner Architects.

3. Elliot resigned in October 2006 at the end of his five-year tenure and was replaced by Nanjo Fumio, the deputy director and an influential independent curator.

5. A couple of definitions are necessary: my use of “history” refers to a theoretical approach to history known as “cognitive realism,” or a tacit assumption that there exists an actual historical reality beyond our senses about which we can obtain increased knowledge through assiduous research. Cognitive realism is not to be confused with “naive realism,” which assumes a past reality that is directly reflected in already available sources and narratives. Second, I use “popular” as something both favored by the people, who have some sense of agency, and as something produced for the people, who also exist as the object of technological developments and social actions. Without going into too much detail, suffice it to say that, in my view, popular culture comprises social formations that mark and sustain, for an indeterminate period, some kind of distinction among the ubiquitous elements of everyday life. What is popular then is that which has been framed and mobilized from among that which is everywhere, and has, as a result, become topically conspicuous. The question of why one ubiquitous thing and not another achieves popularity is related to who or what are the agents of the process of selection and mobilization and framing. The spectrum of agents ranges from the power bloc, the bourgeoisie, and the elite, to the working classes and the subordinated and disempowered. No single agent or agency has sole responsibility, although one may wish to claim that privilege. Popular culture thus is the result not of a homogeneous will—although it can be deployed in an attempt to create one (as in the case of a national popular culture)—but of many wills that sometimes overlap and appear to coincide and at other times are antithetical (Robertson 2001 [1998], chap. 1).

6. For extensive information on the genre of war art, see Tsuruya 2005.

7. For more information on nenpyō see Robertson (2005) and Yamaguchi (2005).

8. Harootunian 2000: 34–94; Mizuno 2009: 1–2.

9. The Ministry of Education was renamed the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in 2001.

11. McCormack 2000: 57; Gerow 2000.

13. Yokohama adopts nationalistic junior high history textbook, 2009.

14. The sect is one of the newest of the shinkō shūkyō, or newly established religions. Some were founded in the mid-nineteenth century but most—and there are hundreds—date to the period following World War II. They tend to be syncretic and millennarian, and led by charismatic (and sometimes megalomaniacal) men and women.

15. Okawa’s boasts in this regard are preposterous and even slanderous. The sect and party maintain slick websites in Japanese and English with links to Okawa’s rambling proclamations and prophecies. I am deliberately not providing their urls; readers can find them easily on Google if they wish.

17. Robertson 2001 (1998): 212.

18. Robertson 2001 (1998): 12–14.

19. Imao 1982: 147–153; Robertson 1992: 423–425.

20. Bryson 1995: 74–75; see also Morimura 1996.

21. Robertson 2001 (1998): 215.

22. Available on line at [http://www.artquotes.net/x-art-quotes-jan04.htm].

23. DiPietro 1998; Lubow 2005.

25. Japlish is the term for Japanese-English and also the Japanese pronunciation or abbreviation of English loan words.

29. Robertson 2007: 372; 2009 & forthcoming.

30. Information here and elsewhere on Innovation 25 is from [http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/innovation/index.html]. See Robertson (2007) for a more extensive analysis of Innovation 25 and for an introduction to the Japanese family of the near future.

33. Coulmas 2008. Coulmas presents Japanese synonyms for “happiness” and reviews academics’ musings on happiness and books on the subject.

35. Available online at [http://www.leader-values.com/Content/detail.asp?ContentDetailID=1025]

WORKS CITED

Bryson, Norman. 1995. Three Morimura Readings. Art + Text 52: 74–79.

Coulmas, Florian. 2008. The Quest for Happiness in Japan. Working Paper 09/1, Deutsches Institut für Japanstudien (Tokyo). Pp. 31.

DiPietro, Monty. 1999. Takashi Murakami at the Parco Gallery. Available online at: [http://www.assemblylanguage.com/reviews/Murakamii.html].

DiPietro, Monty. 1998. Takashi Murakami at the Tomio Koyama Gallery.

Available online at: [http://www.assemblylanguage.com/reviews/Murakami.html].

Elliot, David. 2003. “Why Happiness? A Survival Guide.” In Happiness: A Survival Guide For Art and Life. Eds. David Elliott and Pier Luigi Tazzi, pp. 9–22. Tokyo: Tankosha.

Gerow, Aaron. 2000. Consuming Asia, Consuming Japan: The New Neonationalistic Revisionism in Japan. In Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany, and the United States. Eds. Laura Hein and Mark Selden, pp. 74–95. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Harootunian, Harry. 2000. Overcome by Modernity: History, Culture, and Community in Interwar Japan. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Hongo, Jun and Alex Martin. 2009. Rhetorical Hatoyama Opens Diet. Japan Times, 27 October.

[http://www.artquotes.net/x-art-quotes-jan04.htm].

[http://www.leader-values.com/Content/detail.asp?ContentDetailID=1025].

Imao Tetsuya. 1982. Henshin no shisô (The idea of metamorphosis). Tokyo: Hôsei Daigaku.

Lee, Simon. 2003. Liberty Leading the People (1830). Painting by Eugène

Delacroix. Available on line at: [http://www.routledge-ny.com/ref/romanticera/liberty.pdf].

Lubow, Arthur. 2005. The Murakami Method. Available on line at:

[http://www.howardwfrench.com/archives/2005/04/04/the_murakami_method/].

Mackie, Vera. 2004. “Understanding through the Body”: The Masquerade of Mishima Yukio and Morimura Yasumasa. Available online at:

[http://www.cccs.uq.edu.au/index.html?page=16868&pid=0].

McCormack, Gavan. 2000. The Japanese Movement to “Correct” History. In Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany, and the United States. Eds. Laura Hein and Mark Selden, pp. 53–73. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Mizuno, Hiromi. 2009. Science for the Empire. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Mori, Yoshiko and David Elliott. 2003. “Forward.” In Happiness: A Survival Guide For Art and Life. Eds. David Elliott and Pier Luigi Tazzi, p. 7. Tokyo: Tankosha.

Morimura Yasumasa. 1996. Morimura Yasumasa, The Sickness unto Beauty: Self-portrait as Actress. Yokohama: Yokohama Bijutsukan.

Robertson, Jennifer. 1992. The Politics of Androgyny in Japan: Sexuality and Subversion in the Theater and Beyond. American Ethnologist 19(3): 419–42.

Robertson, Jennifer. 1997. Empire of Nostalgia: Rethinking ‘Internationalization’ in Japan Today. Theory, Culture and Society 14(4): 97–122.

Robertson, Jennifer. 2001 (1998). Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular Culture in Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Robertson, Jennifer. 2009. Gendering Robots: Posthuman Sexism in Japan.

MIT Comparative Media Studies Podcast 6 March. http://multimedia.boston.com/m/21960537/podcast_gendering_robots_posthuman_sexism_in_japan.htm?pageid=13457.

Robertson, Jennifer. Forthcoming. Gendering Humanoid Robots: Robo-sexism in Japan Body and Society.

Silverberg, Miriam. 2006. Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Takarazuka Kagekidan. 1989. Takarazuka.

Takarazuka Kagekidan. 2003. Takarazuka: The Land of Dreams.

Tsuruya, Mayu. 2005. “Sensô sakusen kirokuga (war campaign documentary painting): Japan’s National Imagery of the ‘Holy War,’ 1937–1945.” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of History of Art and Architecture, University of Pittsburgh.

Wakasa, Mako. 2000. Takashi Murakami: Interview. Journal of Contemporary Art. [http://www.jca-online.com/murakami.html]

Yamaguchi, Tomomi. 2004. Feminism Fractured: An Ethnography of the Dissolution and the Textual Reinvention of a Japanese Feminist Group. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan.

Yokohama Adopts Nationalistic Junior High History Textbook. 2009. Japan

Times, 5 August. Available on line at [http://search.japantimes.co.jp/print/nn20090805a2.html].

Yoshida Reiji. 2007. Sex Slave History Erased from Texts; ’93 Apology Next? Japan Times 11 March.

Yoshizoe, Yasuto. 2007. Japanese Statistics and Happiness Measurement.

Second OECD World Forum on Statistics, Knowledge and Policy, Istan-

bul. Available on line at [http://www2.dpt.gov.tr/oecd_ing/dolmabahce_b/27June2007/14.30-16.00/5Yoshizoe_Happiness.pdf].