THE SUMMER OF 1938

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In July 1938 my father had a brilliant idea. He would send me, his fourteen-year-old only son, to spend at least part of what most likely would be a very hot and unpleasant summer in Vienna visiting my mother’s brother Victor in Berlin instead. Four months earlier Hitler had marched into Austria, and the immediate, helter-skelter application of all laws and regulations designed to excise Jews from society had created chaos among the Jews in Vienna. Public harassment of individual Jews on the streets was a common occurrence and could range from attacks from wildly physically abusive passersby to cleaning the sidewalk with a toothbrush. All Jewish students of high-school age had attended their last school day at the end of the spring semester in June and were henceforth barred from any further formal education. Teenagers like me were now at a loss for how to spend their time, other than staying at home to avoid any confrontations. Obviously we weren’t going to do that, and we flocked to the public parks where we would congregate until either the local HJ (Hitler Youth) group or some other public-spirited, freshly baked German citizens demanded our departure. We did not always follow their commands and scuffles were not infrequent. I had come home once or twice with a bloody nose or black eye that caused some awkward discussions with my parents. Once I was also caught in a small fracas at a local Konditorei where we met on rainy days. I can’t remember the particulars, but when some of my friends beat a strategic retreat I was among the last ones to slip through the exit, a large glass door, that closed with a mighty crash behind me, shattering glass all over the sidewalk. I stopped and turned around to look, and that was when the owner grabbed me while his wife called the police. Others must have called even earlier because the police were there in minutes, and before I knew it a detective was interrogating me on the street. That was when I first realized it wasn’t always about Jews and Nazis: taking notice of my youth and the impossibility of my having deliberately smashed the glass door, as claimed by the owner, he put me in a police car, told the driver to take me home, and warned me that if I got involved in something like this again, it wouldn’t go as easy on me. When I got home rather late for supper, pale and obviously shaken, father conceived his plan to put me out of harm’s way with his brother-in-law in Berlin.

Vienna was rife with all kinds of rumors at that time, relating mainly to opportunities for emigration or what might happen if Jews had to remain in Germany. At a conference hastily scheduled in Evian, France, no government—including the U.S.—had been willing to open its borders to any Jewish refugees from Germany. My father’s only hope lay in contacting some distant relatives in America for possible emigration there. That would take time, requiring among other things the petitioning of all kinds of German authorities for the documents necessary to permit emigration, and worst of all the queuing up at the U.S. Consulate to register for a quota number. In July 1938 thousands were intent on doing just that, and one could expect days of standing in line. My parents knew that they would be out of the house for most of the day and that supervision over my activities would range from scant to nonexistent. A phone call to Victor cleared the way for my visit that very evening. The two brothers-in-law were very close and had a great liking for each other. Victor also had only one child, a daughter, Hannah, who was four years older than I was and whom I adored. Her mother, my aunt Hedi, was approximately my mother’s age (thirty-nine or forty), a lot of fun, and very permissive. And so it happened that one of the most glorious summers of my childhood was spent as a fourteen year old in the capital of Nazism, Berlin. The idea of visiting there excited me no end since, from my point of view, Vienna had always been rather provincial compared with the great metropolis to the north, especially now when Austria had truly been demoted to the rank of a province and renamed “Ostmark.”

Victor and his wife Hedi (short for Hedwig) had moved to Berlin during the 1920s. Victor opened up a jewelry store with very modern designs originated by Viennese artisans (Wiener Werkstatt) which were very popular at the time. His business prospered—he even opened a second store in Hamburg—and Hitler’s coming to power in 1933 had no adverse economic or financial consequences for Victor’s business. On the contrary, on the occasion of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin Victor enthused about his business experiencing a “second Christmas.” Responsibility for this odd development lay with Victor’s citizenship, which remained Austrian, marking him as a foreigner who brought in hard currency and therefore untouchable. Thus, though socially and culturally the life of the Schab family in Berlin was as circumscribed as that of other Jewish families at the time, the success of the business permitted Victor a fairly lavish lifestyle. The family lived in a luxurious apartment house in the very leafy part of Grunewald, drove a BMW coupe, and still enjoyed the services of an “Aryan” maid, unmolested by prying, anti-Semitic neighbors or the watchful eye of the local NS party cell. Reichskristallnacht was still several months away, and even the annexation of Austria earlier in the year had not appreciably changed the lifestyle of this family.

Thus it happened that after an uneventful overnight train trip in a sleeping compartment which I shared with an elderly couple and a single gentleman, I arrived one morning in July at the Anhalter Bahnhof, then Berlin’s largest and most famous railroad terminal. Uncle Victor was waiting for me on the platform but his joyful, laughing face froze when he saw me alight from the train with—an SS officer! It was the single gentleman who, prior to our arrival, had shed his civilian clothes for the uniform, which in no way however changed his demeanor toward the elderly couple or me. He had questioned me the night before about where I was going, and I had answered truthfully that I was about to visit my uncle in Berlin. That had been the extent of our conversation. When he saw my uncle greet me he wished me good luck and raised his hand in a very perfunctory Heil Hitler. My uncle didn’t say a word until we were in his car and on our way home, and even then he just wanted to know whether the SS man had asked me for my name or his address. When I answered in the negative he shook his head and shrugged his shoulders. That I remember this incident at all is due to the fact that later, at dinner with the family, he related this encounter, which was greeted with raucous laughter by my cousin Hannah and her fiancé, Emil.

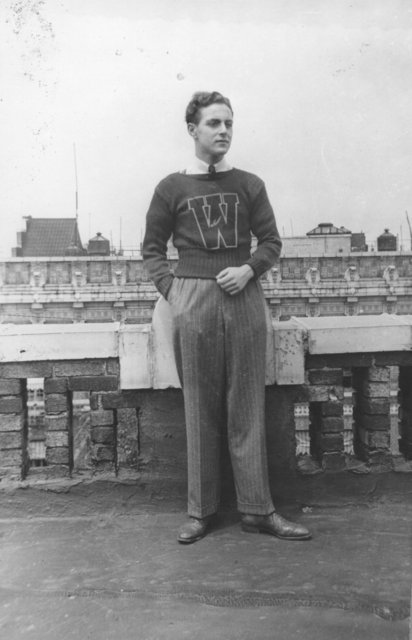

In Berlin, at least at that time, outright provocation of Jews on public streets was no longer common. Both Nazis and Jews assumed that emigration would soon take care of most of the German-Jewish population, which in the process would be “legally” relieved of its property and financial holdings. Hannah and Emil were both active in a Zionist youth organization, and I understood they expected eventually to settle in Palestine. Both were outdoor types, loved hiking, camping, and biking, and generally affected a simpler lifestyle than their parents; Emil also came from an extremely wealthy, German-Jewish family, one closely related to the Mosse/Ullstein publishing empires. Both Hannah, 18, and Emil, 21, dressed only in denim walking shorts with similar, rather shabby bluish blouses and hiking shoes, an outfit they always referred to as their “Kluft,” a term that emphasized its ordinariness. They were rarely home, always off to some meeting or organizing event, but never failed to invite me to come along or otherwise treated me as an equal, engaging me in conversation about recent events in Vienna, movies, or other topics that interested us. I in turn pumped them about Berlin, the city which to me at the time appeared as the center of the world and which, as a fourteen year old, I was fully prepared to explore whenever the occasion presented itself. There was no lack of opportunity, for Aunt Hedi had no intention of acting as my mother surrogate. So when I took off on my excursions through the city she always outlined the shortest routes by public transportation, instructed the maid to make me a sandwich to take along, and was always happy to see me again later. As long as I appeared in time for dinner and went to bed at a reasonable time, I could have the day to myself. I made the fullest use of my freedom. I should probably mention that in principle that was not too unusual in those days, when teenagers were not expected to be chauffeured by their parents to their various destinations. Ever since I had turned twelve I had walked or ridden the trams all over Vienna without any supervision—and so had most children of my generation; it was a different time.

Dressed in my lederhosen, with a matching green loden jacket adorned with very decorative silver buttons, capped by a Tyrolean hat with a small feather (definitely not a “Kluft”!) I crisscrossed Berlin at will on buses, trams, and metro lines. This neat, well-behaved, and rather cute young boy, so obviously an Austrian visitor, was never asked why he was not in the uniform of the HJ, as might have inevitably happened in the Vienna of ’38. Unlike in Vienna, the street picture in Berlin was devoid of uniforms; neither the mustard brown shirts of the Party nor the military gray-green were much in evidence. In fact the only men in party uniforms I recall were those with swastika-covered metal boxes soliciting passersby for aid to the poor during the cold season (Winter Hilfe). When I had to ask for directions—to a museum, a U-Bahn (metro) station, et cetera, people were always friendly and pointed me on my way. It never occurred to me that I could be in any danger. I have no idea how I would have reacted in answer to a question of whether I was Jewish or what the consequences might have been for me had I replied affirmatively. Thank God that never happened. Also, my situation was really not as unthinkable as it sounds today. By the time of that summer the regime had been in power for five years—during which the ’36 Olympics had been a huge success—and its concern with keeping publicly alive a smoldering anti-Semitism was no longer as pressing as it had been earlier. By now the laws and institutions were in place to excise the Jewish part of the population from German society. The public paranoia that had gripped the general population in Vienna after the Anschluss was noticeably absent in Berlin. I might add here that, again unlike in Vienna, Berlin Jews for some time had already enjoyed the experience of the Jüdischer Kulturbund, which provided theater, cabarets, and other entertainment of an exceptionally high quality for Jews who had been prohibited from attending regular performances in the city. All this of course, proved to be merely temporary, ending catastrophically with the Reichskristallnacht; I was merely the unsuspecting beneficiary of this short-lived situation.

It was indeed a crazy summer for me as I explored the capital of Greater Germany. Well-read youngster and admirer of Erich Kästner that I was, to me the city spoke primarily of his best-known work, Emil and the Detectives. This almost epic story centered on a group of smart and spunky young boys and a girl who set out to catch a thief, with the help of the friendly police and to the applause of eager neighbors and dependable friends. In the course of that effort they covered a sizeable part of the city, whose street names, landmarks, and districts were soon as familiar to me as were those of my own hometown of Vienna. I knew my way around the area of Nollendorfer Platz, Tauentzienstraße and Joachimsthalerstraße, the Tiergarten district, et cetera, just from reading that book. But I also ventured into the less appealing parts of Berlin, such as the working-class districts of Gesundbrunnen and the “Rote” (Red) Wedding, so called because its inhabitants voted, prior to Hitler, almost solidly for the Socialist and Communist parties. That information I had gleaned from some of the modern, very adult novels—including those by Kästner—I found and read in my uncle’s library.

My travels included visits to the Funkturm, the recently erected radio tower that, in my estimation, equaled the Eiffel Tower, which I had never seen. The exhibition grounds adjoining the tower were at that time featuring the latest achievements in wireless broadcasting technology, and I was able to watch early TV shows broadcast from one building to another. The receivers were fitted out with mirrors that reflected correctly whatever entered the screen upside down. I was very impressed and so were undoubtedly the other visitors, since this was the most crowded exhibit. In my excursions one late afternoon I found myself in front of an impressively illuminated building where a large crowd was awaiting the appearance of Hitler on a small balcony that jutted out not far above the crowd. This particular occasion was the visit of the Prince Regent (Reichsverweser) of Hungary, Admiral Horthy, and the first head of state to honor the Führer with a visit following the internationally condemned Anschluss earlier that year. I was on the edge of the waiting crowd, having arrived rather late, and within minutes was able to get a good look at Hitler and his guest. Interestingly, Hitler wore white tie and tails, in contrast to Horthy, who was resplendent in his naval uniform (as the temporary head of government until the reestablishment of the kingdom, he naturally assumed that there would also be a navy again). The crowd cheered, the two important political figures waved to the crowd—no raised arm salute by Hitler—the crowd waved back with only a few arms raised in response. I was so nonplussed at actually seeing Hitler in the flesh that I most assuredly did not raise my arm—and I guess because I was small this absence of gesture went unnoticed. Fortunately the two heads of state did not linger long; they were preparing to attend the opera (Wagner, I presume!) as I learned from the conversations of the rapidly dispersing crowd around me. This accounted for the evening-dress splendor of Hitler. When I regaled my uncle and aunt that evening with this latest experience, they cautioned me to be more careful in the future with my wanderings but otherwise did not express any great surprise or fears for my person. One day I even went to see a movie in the resplendent Gloria Palast, where a small Zeppelin hovered above the spectators during intermission spraying a delightful aroma throughout the theatre. Sometimes during the day when I was in the neighborhood and felt tired or hungry I would drop by my uncle’s store, Die Wiener Industriewaren Centrale (WIC), located conveniently almost in the center of the city’s fashionable business district on the Tauentzienstraße within sight of the Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche, a site that after World War II became famous as a landmark commemorating the city’s bombardments by the Allies. As a matter of fact, Victor’s jewelry store was still doing good business even though technically he was no longer a foreigner who could count on the protection offered by his Austrian passport. Then Uncle Victor would treat me to a quick bite at Aschinger’s, a buffet-type eatery that I loved for its many varied selections—similar to Horn & Hardart which, many years later also became my favorite fast food place in New York. Thus invigorated I set out again on my perambulating adventures—always taking care to be home at the Grunewald residence, not far from the tram terminal Hundekehle, in time for dinner, usually quite lavishly prepared and served by the “Aryan” maid.

There were other pleasant recollections of this summer in Berlin. I went bicycling or swimming in the Grunewald lakes with Hannah. We visited friends of the family, who still resided in impressive mansions on or near the Wannsee, where maids in white aprons and black blouses served Kaffee und Kuchen or what we in Vienna called, inexplicably, Jause. Conversations turned inevitably toward the situation in Austria, the opportunities for emigration for younger people such as my cousins and their friends, usually mentioned in a tone of resignation implying that the older generation would have to stick it out until this regime would unavoidably collapse. I don’t recall any great nervousness about developments in Berlin in the immediate future. In any case where was one supposed to go, unless one had financial security in another country, preferably England or France? And that was hard to come by, since the price of emigration meant giving up under duress most of one’s holdings, here or abroad, to the Nazi government. The unwillingness of other countries to accept destitute Jewish refugees had been made abundantly clear at the just-completed Evian Conference. America’s stringent immigration laws made any hope for a quick exit to that country equally improbable; besides, few German Jews had relatives in the States—that was a privilege reserved chiefly for those whose origin in Eastern Europe, Galicia, et cetera, was of more recent date. It was this latter fact that enabled my family eventually to make it to America by sheer luck.

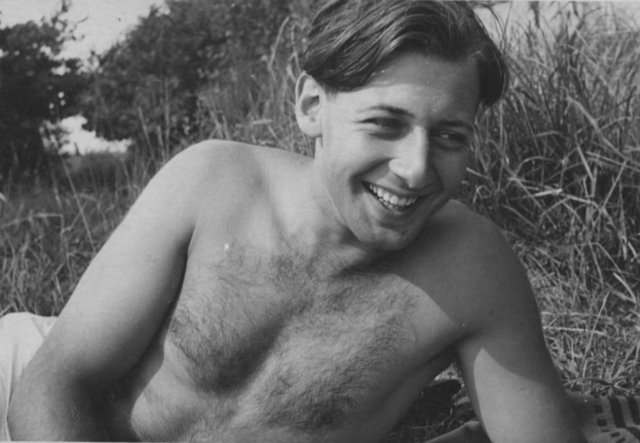

Under these circumstances it was therefore not at all surprising that Hannah and Emil—whom everyone called “Mümmel,” a holdover from his toddler years when he could not yet pronounce his full name—decided to go camping along the Baltic coast, near the town of Rostock. A friend, Achim Gruenwald, who owned a car, an Opel, would provide transportation. Since this sounded pretty exciting to me, I asked whether I could join them. Both Victor and Hedi appeared quite amenable to this suggestion—after all it would relieve them for a time of some immediate responsibility for me—and they approved laughingly, calling me a chaperone for Hannah. Mümmel and Hannah also welcomed my presence, and so off we went one morning on a carefree trip to the Baltic coast. For me the trip offered two “firsts”: a long trip in an automobile and seeing a real ocean, a quite exotic sight for a boy raised in an inland country. Nobody cautioned us to avoid Nazis or behave inconspicuously, or in any way pretend to be something we were not, i.e., “Aryan” Germans.

Our destination turned out to be a sand dune separated by only a few steps from the ocean. We just barely found an ideal spot for pitching our tent. This obviously quite popular camping place was already crowded with colorful tents and lots of young people busily enjoying the surf, shouting, dancing, singing, and otherwise having a good time. Not a brown uniform or swastika Wimple (pennant) in sight. Not that we were looking around to make sure there weren’t any—that never occurred to us as we headed for the first vacant spot in sight. Neither did we look around to check who our neighbors were. I was in seventh heaven; this was real camping as I had always dreamed about, in a tent that we all shared and with a little oven Mümmel had carved out of a two-gallon metal container that we fed with wood and some small pieces of coke. We had brought supplies, and what we didn’t have we bought at a small store in the village nearby. Happiest of all, I could indulge in my newly acquired “adult” habit of smoking a pipe! We swam, we played, we sang around our campfire, and we made friends with several of our tent neighbors. One of those was a very attractive young single mother with a small baby, who had become smitten with our Opel-driving friend. Achim returned the feeling and, as I learned much later, kept on seeing this young woman in Berlin. Though they did break up eventually, the Nüremberg Laws prohibiting contact between the sexes of different “races” apparently did not deter them from starting the relationship. We spent about ten days in that campers’ paradise, blessed most of the time with good, warm, sunny weather, a condition not met with very often on that northern coastline. On the next to the last day of our sojourn there, a very jovial-looking local policeman made the rounds of the tents, chiefly to make sure that certain safety precautions relating mainly to clean-ups would be observed. He stuck his head into our tent where we were already preparing for our departure the next day. As I recall we exchanged a few perfunctory remarks and he was just about to turn away when he said in a rather bored manner: “Of course, you’re not Jewish, are you?” When Mümmel answered in the affirmative, the policeman seemed to be as ill at ease as we were. Without changing his manner, he then suggested that we should go to the local police station in the village the next day where we could register. With a weak salute (no Heil Hitler) he then continued on his round. For a while we discussed this incident and then decided not to register but simply be on our way the following day as we had planned.

This camping trip to the Baltic would become a defining moment in the relationship with my two cousins. On my seventieth birthday I received from them for the first time some excellent photos of this trip, with a sweet letter from Emil (nobody called him Mümmel any longer) evoking those halcyon days. Even more recently I have learned of a postscript to this trip. This was related to me by Emil, then 84, in a letter to me dated September 6, 2003. The passage deserves to be quoted here in full:

. . . The glorious time we 4 had at the Baltic Sea—especially glorious for Hannah and me when we disappeared in the dunes just the two of us—did have a sequel from the visit by the policeman. Some time in August I think, shortly after you had left, Achim, Hannah and I were ordered to appear for an interview at the Gestapo headquarters on Alexander Platz. It was frightening when the gates clanged shut after entering. We were interviewed, at times roughly, but nobody ever touched us, about what we were doing there at the Baltic. They implied that they believed it to have been a secret meeting of youth groups or something like that. Yet nothing happened to us. . . . we had to wait in an ante-room and were called singly into the interview room several times. At a later stage while we waited again, the woman secretary-stenographer came out and as she passed us I approached her asking whether we had a chance to be out by a certain time, as my brother was leaving that day for Australia. She did not answer and walked on— there were other people sitting there—but after a while she came through again, and as she went past us without stopping, she said out of the side of her mouth: “You’ll be out in plenty of time.” Turned out to be true. Interesting, isn’t it . . .”

Today I recall only that on the day of my return trip to Vienna—it must have been late September—the news vendors on the railroad platform kept shouting something about an agreement reached, or about to be reached, in Munich. I most probably bought a paper in order to have something to read on the long night trip to Vienna, but I certainly did not grasp the significance of that event. For that I had to wait until I entered college in America.

This quasi-normal, semi-insulated existence of German Jews ended with the assassination in Paris of a German Foreign Service official, von Rath, by a desperate young Jewish student named Herschel Grynszpan on November 7, 1938. It was followed almost immediately by a centrally directed and manipulated uprising of chiefly Nazi-related organizations that ended in the violent destruction of nearly all synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses in Greater Germany. This event entered history as Reichskristallnacht, “Night of Broken Glass.” Victor’s store, the Wiener Industriewaren Centrale, also was demolished on that night.

Now even Victor Schab realized that he and his family would have to abandon their home in Berlin before they, too, fell victim to whatever future Nazi terror was awaiting them. Hannah and Emil hurriedly got married and, after a short honeymoon trip to Vienna to meet the Viennese members of the family, returned to Berlin. Emil almost immediately flew to Palestine, there to wait for Hannah. They had applied for an Australian immigration entrance visa but Hannah’s visa had been held up by the Australian authorities, who had voiced some suspicions regarding her sudden marriage to Emil. After a tense wait of several weeks Hannah obtained her visa and joined her husband in Palestine. Together they flew to Sydney, where they met Emil’s brother and began their new life “down under.” Hannah was already pregnant, and almost exactly nine months later she gave birth to their son Nick, the first member of our family born abroad. We did not meet again until thirty-odd years later.

Victor and Hedi on the other hand had absolutely no chance to emigrate anywhere overseas at the beginning of 1939. Since his brother Willy was the only one who could provide him with the necessary guarantees for the issuance of an American visa, he had to wait for Willy to arrive in the U.S., which would not occur until, at best, much later that year. Furthermore, Victor’s registration in late 1938 at the U.S. consulate for a place on the quota list might not permit his entry until at least two or three years later. His decision to move quickly to Riga, Latvia, was motivated by two further considerations. He would be able to take along considerable German currency to that country without arousing the suspicion of the authorities, and he was helped in this undertaking by his longtime secretary and store manager, a very attractive woman “in her best years,” as they used to say in those days, who was a citizen of Latvia. A very efficient business manager, she had for many years also been in a liaison with her boss. She was Jewish and lived with her parents, who were friends of the Schab family. I had met both her and her parents during my visit at Victor’s home. Hannah seemed to know about the relationship, and Hedi almost certainly did and, according to Hannah, brought it up occasionally during altercations with Victor. The woman’s father was arrested on Kristallnacht and sent to Dachau, where he died allegedly of a heart attack—the body was shipped back to his family in a closed coffin which they were prohibited from opening. Soon afterwards Victor and Hedi, together with the woman and her mother, departed for Riga.

My return to Vienna did not cause any great excitement among my family, nor were my friends particularly interested in my stories about the capital of Nazi Germany. Everyone’s concern in that early fall was over the opportunities for emigration, which were slim, indeed. My parents had, in the meantime, received the necessary guarantees from my father’s relatives in New York, and all we had to do now was to wait patiently for our notification by the U.S. Consulate.

Suggestions that we should just pick up and leave for some other, any other, country in Europe were firmly rejected by my father. He insisted that the takeover of the remaining European countries by Hitler by whatever means was merely a matter of time and the only place that made any sense was America, end of discussion. Kristallnacht, which we survived relatively unscathed, only reinforced his determination. Personally I continued my rather carefree existence, though the circle of my friends and the places we could meet shrank perceptibly. I took advantage of several adult education courses offered by the Viennese Jewish Community organization, which were designed to impart to prospective immigrants salable skills once they started a new life in another country. Thus in quick succession I enrolled in a course on fashion designing, followed by plumbing and another one in shoemaking, and with the arrival of spring I turned to gardening. Each one of these courses provided me with a certificate of successful conclusion, though I doubt that I could ever have qualified as even an apprentice in these trades. Quite a number of my contemporaries were sent to England by their parents on the so-called Kindertransporte that were now leaving at regular intervals. A very few whose parents had registered early in April or May 1938 actually departed for America. The rest of us began meeting in each other’s flats until, in the spring of ’39, we were all gradually evicted from our original residences in order to make room for deserving Nazi Party stalwarts. My mother and I moved into a room in an apartment that we shared with several other families, and my father moved in with his sister. Supervision over my activities outside the “home” became less and less stringent. For a couple of months I became the English tutor of a boy, Hans Nagler, who still lived with his mother in a luxurious home in one of the classier suburbs of the city. He was scheduled to leave on one of the Kindertransports. Since I had started learning English from kindergarten up, I was quite conversant, and I assume the boy profited from my teachings once he arrived in England.

A very young maid who was not averse to engaging in some petting with the tutor while little Hans did his written exercises was still serving the household. That idyllic interlude came to an end when a local Nazi bigwig finally entered his claim to the house and the Nagler family was unceremoniously booted out. I lost my job, Hans left for England, but his mother (there was no husband) had to remain behind.

By that time the summer of ’39 had arrived, and for the Jewish boys and girls still in Vienna it lay ahead as a threatening void, with nothing to do and nowhere to go for entertainment. The beautiful municipal swimming pools, built during the early thirties and once the pride of the Social Democratic administrations of the City of Vienna, were now off-limits for Jews. But just before the summer heat became too oppressive, someone in the Nazi government of the city began to express fear that without some open-air places for swimming and sunbathing for the cooped-up Jews, the city might be courting some kind of epidemic. A rather large pool and sport area outside the heavily built-up areas of the city was reserved for the Jews’ exclusive use. It was located in the suburban area of Baumgarten and could be easily reached by metro. We were at first reluctant to make use of that privilege, fearing that we would be sitting targets for raids by the local Nazi district groups. But the Jewish Community Organization sent out letters taking credit for this new arrangement and assuring its members that the local security police would protect them. That turned out to be true, and most of us spent June, July, and part of August happily cavorting in the Baumgartner Bad. There were also some parks in the inner city still heavily frequented by foreign tourists where we could mingle safely without much fear of confrontations. Occasionally we would meet in a loftlike apartment of one of the boys, whose father, a lawyer, had been arrested earlier and was serving time (“real time”) in one of the city prisons. His mother left the house early and did not always return the same day. There we danced to records on a gramophone—our favorite was “Bei Mir Bist Du Schön,” which, incongruously, was then sweeping Europe—played cards, drank some wine, and sought other pleasures with the girls in our crowd.

Two memories stand out from those summer months. One of the boys told us of a Jewish prostitute who could no longer ply her trade on the street without the required health permits. It was issued now only to “Aryan” whores by the city, and therefore she was willing to receive clients at her home; her eagerness was also fueled by the need to obtain passage money for eventual emigration to America. Some of us took advantage of this opportunity to enlarge our experiences and, as I recall, none of us was the worse for engaging in that kind of “short-term” relationship. Viennese youth, Jewish or not, was well acquainted with the means available for protection against STDs. The second memory that has stayed with me was the arrival in our circle of two boys, closer to seventeen than my fifteen, who bragged openly that they were making good money satisfying the sexual needs of foreign tourists, chiefly Turks and Arabs. They would spend their days with us, playing and sleeping—they said they had no homes to go to—and in the evening both of them, slightly rouged, would hit the bars on Kärntnerstraße and the narrow alleys off the Graben, the crowded area adjacent to the cathedral where nightlife catered to all tastes. Sometimes they’d tell us in great detail of their experiences and always insisted that the boy in whose home we met would take his share of their profits; for the rest of us they’d bring American whiskey and other edible delicacies from the places they had visited.

This obviously dissolute lifestyle came to an end for all of us with the announcement of the Hitler-Stalin Pact early in August, and the closing of the Baumgartenbad. Our friend whose loft had become such a convenient meeting place for our pleasure-hungry crowd departed for the Far East on a Shanghai visa, one of the very few means available to circumvent the immigration barriers erected by nearly all countries and leave Germany for a highly uncertain future. The visa cost ten U.S. dollars, and with it one could book passage for Shanghai and obtain the necessary transit visas. Before I had time to adjust to the new situation, Hitler declared war on Poland, and the French and British returned the favor. That event too is indelibly etched in my memory because on that same day also arrived the notice from the U.S. Consulate asking my parents and me to present ourselves for the medical examination required prior to the issuance of the immigration visa. That date was set for October 10, and there ensued an incredible four weeks of packing, obtaining documents, scrounging around for money to cover our passage via Italy to New York, and saying goodbye to relatives staying behind. We were able to secure passage on the Saturnia, an Italian line cruise ship that would leave Trieste on November 2 and arrive in New York on the seventeenth of that month. We thought the only risk would be that Mussolini might join his Axis partner, thereby closing the Italian ports as well. Lucky for us and many others he didn’t at that time. But another obstacle loomed when a few days prior to our departure an official communication from the Viennese Jewish Community Organization ordered us to meet with others at the North Railroad Terminal on October 30, bringing not more than one suitcase, for resettlement in Poland. Adolf Eichmann had arrived in Vienna and was taking charge of the lagging Jewish emigration. Father immediately went to the offices of the Jewish Community Organization, and only because he could show them the U.S. visa in our passports were we relieved from having to follow the new orders. We left as scheduled on October 30 for Trieste, leaving behind two grandmothers, two aunts—sisters of my father and mother—and the husband of one. All but one perished in the camps—my father’s mother fortunately died of a natural death a few days before Pearl Harbor, but it wasn’t until 1946 that we learned of the fate of all five of them. Victor and Hedi Schab, together with their friends, were murdered in the massacres of Jews that followed the German invasion of Russia in June 1941. Hannah and Emil raised three children and were able to enjoy six grandchildren. Little Hans Nagler’s mother was able to correspond with her son by means of my father in New York until Germany declared war on the U.S. Her fate too, remains unknown. As for me, I was lucky enough to reach New York only a few days before Thanksgiving Day 1939, which thanks to FDR had been moved forward a week in order to extend the Christmas shopping period. I entered high school immediately after that holiday and embarked with enthusiasm on that to me most satisfying task of becoming an “all-American” boy. Whether I achieved that is for others to say.