Power Lunches in the Eastern Roman Empire

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

A lecture delivered on April 4, 2003, on the occasion of Professor Alcock being named the John H. D'Arms Collegiate Professor of Classical Archaeology and Classics at the University of Michigan

You might be wondering about my title. Even in this depressed economy, you can all still envision the spectacle of a "power lunch": that scene of extravagant eating, drinking, and even more extravagant billing, of collusion, coercion, and power plays around the table. Meanwhile, if you put the notion of "food" anywhere near the concept of "the Roman empire," an equally immediate, and still more fantastic image springs to mind: of wild parties, unimaginable meals, of excess beyond belief.

Both these phenomena are appropriately invoked in a lecture intended to do honor to John D'Arms. Let's face it, John was not uninterested in power and its operation; he was a worldly guy. But, much more importantly, he was a long-term student of asymmetrical human relationships, a student of interaction (easily evolved or painfully enforced) between individuals of different status in the Roman world. Just as significantly, he became in his later career a central figure in ancient food research, helping it mature into the increasingly sophisticated subdiscipline of classical studies it is today. If "Roman food" was once all about the "ooh ahh" factor (flamingo tongues, vomiting, and, of course, the inevitable orgies), John saw far beyond. Mind you, he could tell an outrageous and salacious "bad food" anecdote with the best of them (I've seen him do it!). But he also pushed continually for more rigorous analyses of Roman dining practices—the commensal relationships forged, the hostilities created, what currents lay beneath the deceptive surface of our sources.

In some of John's later writings, a new theme began, I think, to emerge. Our best evidence for Roman foodways, both textual and archaeological, comes from the heartland of empire, from Italy. Our sources, of varying date, have frequently been collapsed together to present a synchronic picture: to represent the Roman dinner party (the convivium); to assert this is "how the Romans ate." As John would say, "this will not do"; and he evinced increasing curiosity about variation in food consumption across the Roman empire. In one of the last things he wrote, John was skeptical of any "kind of seamless coherence in Roman elite constructions of culinary reality"; he deplored "any belief in an unvarying consistency in upper-class dining protocols, rituals and representations"—especially over a span of several centuries, and across a vast empire.

When I read that, I recognized a challenge—and one I admit to having heard before. One of the things that John and I had in common (apart from finding life partners among those CNN terms "the Brits," and an often despairing fondness for the Michigan football team) was an interest in ancient food. I have taught an undergraduate course here at Michigan on the subject, and I have organized a couple of related student exhibits at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. But I never saw myself as a "food scholar," as someone actively researching in this area. And that provoked John, who would stare down at me from what always seemed a very great height, and tell me I was ridiculous. So today, a little late, I want to pick up in at least one place where John left off, and take up this issue of possible alteration and variation. Today, I ask the question—how did eating change with the arrival of Rome in the eastern Mediterranean? To put it another (more sexy) way, did empire influence diet?

Before proceeding—I imagine few people still need educating on why food is "good to think." It should not be news that food is on the academic march. Food, feasts, calories, consumption, cuisine, dining, disorders, drinking, gastronomy, gastro-anomie: all these are developing angles of attack in many fields, all increasingly recognized as offering a good entrée into the study of contemporary and past cultures. Sidney Mintz, for one, put food right up there, along with sex, as "a remarkable arena in which to watch how the human species invests a basic activity with social meaning." And once you get stuck in the mindset, it becomes hard to think "outside" or "around" food: it invests, and creates, our social distinctions, our gender differentiations, our political alliances, our religious affiliations, our constructions of self and other. You are what you eat; you are who you eat with; you are how you eat: cliché city, yes—but these are compelling and valid clichés, and clichés to which we shall return.

Less readily familiar perhaps is my target of attention—the world of the eastern empire, specifically the linguistically and culturally Greek (or largely Greek) provinces of the eastern Mediterranean. I am talking about modern Greece (the province of Achaia, with major cities at Athens and Corinth), Turkey (the provinces of Asia, Bithynia, and Galatia among others; marked by some supersized cities such as Ephesus and Pergamon), modern Syria/Lebanon (Roman Syria, with major centers such as Antioch). I won't bore you with the messy political and military imbroglios of annexation, but let us just say that the region is, by and large, in Roman hands following the battle of Actium (31 bc). Actium, of course, is notorious for being the final defeat of the decadent, food-abusing eastern forces of Antony and Cleopatra by the moral, virtuous west of Augustus, an emperor forever famed not least for his trim figure and his responsible, if boring, diet. And the rest, as they say, is history—or at least kicks off the centuries of the pax Romana, centuries when "the glory that was Greece" passed under "the grandeur that was Rome." Less poetically, my present focus, by and large, rests on the first three centuries ad.

Of one thing we can be sure—people continued to eat with the coming of empire. We can also assume that the usual Mediterranean triad of foodstuffs—the olive, the vine, and cereals—continued to provide the bulk of calories to the bulk of this eastern population. And finally, we can recognize that—compared with some empires—the Romans did not actively employ food and food choices as an imperial stratagem. No force-feeding of forbidden things to subjects (as the British are said to have done in India), no new crops imported and insisted upon (as with large-scale cattle raising in the New World, or the arrival of the kiwi fruit in Greece under the European Union); no McDonald's. But within those rough parameters, there remain a thousand questions we could ask about dietary change in the eastern empire. My motif today of "power lunches" allows the richest mix of data (archaeological and textual), and sticking with the elite echoes John's principal scholarly concern: his interest in reconstructing the social world of the Roman upper classes.

In fact, let me orient my discussion this afternoon around a figure brought vividly to life by John in his book Commerce and Social Standing in Ancient Rome. This is a fellow called T. Flavius Damianus, who lived in the large and affluent city of Ephesus in the mid-second century ad (Figure 1). Damianus was, we are told, a "most illustrious" sophist—sophists were teachers, public performers of rhetorical addresses; they were celebrities known far and wide, even to the emperors themselves. Sophists were VIPs, and Damianus was one of them. He came of an old Ephesian family; achieved Roman citizenship; he married well; his children entered or married into the consular class. He did good: supported the poor, delivered speeches for free, spent on public buildings. And he was, not surprisingly, stinking rich, with income drawn on everything from personal harbor facilities to fruit trees.

Now I have to make a confession. I can't really talk about "power lunches" because lunch was never, ever the big meal in the ancient world. But what we can do, using Damianus as a representative figure, is to ask some very basic questions about elite eating, specifically elite private dining, in the early empire. Three questions: What would Damianus eat? With whom would Damianus eat? And how, in what setting, would Damianus eat? And how do these reflect, or react, to the fact of empire?

In order for these questions (and even more, their answers) to make sense and have meaning, we should take a few minutes to put Damianus and his dining in context, to think a bit more generally about just how the group he represents reacted to imperial domination. On one level, we see such elite individuals going along and getting along in the new Roman system—as Damianus did, becoming a Roman citizen, watching his children join the imperial infrastructure, bearing administrative burdens to keep his city in good order (and good odor!) within the empire. This is all very typical behavior for a man of his place and status, across all provinces. From this angle, the cooptation of Greek elites within the Roman empire appears a relatively smooth and consensual project.

But that tidy outline offers only half a picture. The Greek/Roman-Roman/Greek relationship also contained some deep ambivalences and fissures, running both ways. Certainly the Roman side acknowledged (for better or worse) its own "Hellenization." Roman authorities were, for the most part, philhellenic in orientation—but their respect was rooted principally in an admiration for the Greek past, the classical past of a pre-conquest age. Attitudes toward contemporary Greeks were more mixed; the Graeculi (little Greekies) of then present-day "Old Greece" (rather like Donald Rumsfeld's "Old Europe") were perceived as a people in the twilight of their days—definitely, irretrievably subordinate.

Coming from the other side, the Greeks too made much of their history. Sophists like Damianus would deliver their spectacular tour-de-force declamations, to large and wildly enthusiastic crowds, not on aspects of the here-and-now, but on topics such as fathers of the Marathon dead praising their sons, how to fight Peloponnesian War battles, and so on: in fact, events, episodes, debates of some five centuries before. This "classicism" or this nostalgia, is a pronounced, almost overwhelming aspect of elite cultural logic in the imperial east. It has also been long misunderstood, taken either as vaguely escapist (oh, for the good old days when we built the Parthenon) or—worse—as sycophantic (Romans lap this kind of stuff up. . .). The relative scholarly neglect of the Greeks under Roman rule stems, to an inexcusable degree, from this perceived "embarrassment"—the Greeks were no longer what once they had been.

I've spent some time debunking that distaste (as has a growing wave of scholarship on various aspects of Greek imperial culture). What emerges to replace it is recognition of a persistent, if far from monolithic, streak of "we are different," we are Greek and you are not: an emphasis on separate identity that emerges most effectively in that emphasis on their particular past, on a past unique to them. Far from second childhood or sucking-up, this turn to the past increasingly appears an element in active dialogue with imperial domination; nostalgia isn't weak here, but rather a strategy of self-assertion and a marker of cultural distance.

Enough background. My point is that, far from a straightforward, unproblematic cooptation, this particular contact zone emerges as messy and volatile, with lots of chew to it, and lashings of good post-colonial angst. And this is where I want to insert food.

What would Damianus eat?

It is a good bet that a member of the eastern elite would draw on an extensive range of foodstuffs, of luxuries and delicacies, under the early empire. Certainly we see this in the heartland of Italy, where the acquisition, display, and consumption of rare goodies became a claim to status and influence. Out of numerous anecdotes, perhaps the most famous is that of the emperor Vitellius, a serious piggo. Vitellius had a massive silver dish filled with foods brought from all over the empire (including the famous flamingo tongues) and—putting the world on a plate—he ate the whole thing: consumption as an edible metaphor of power.

This central, vacuum-like appetite for extraordinary commodities had very direct consequences in the east, which became heavily involved in the supply and conveyance of luxuries. A variety of ancient authors attest to this; we can also glimpse it, indirectly, through archaeological evidence, such as the circulation of amphoras, large ceramic storage jars. Sources report the eastern production of highly desirable delicacies such as liquorice (best from Cilicia), Asiatic peaches, Syrian nuts, Attic honey, Cretan wine. Note the toponyms here: not any old liquorice will do! Geographical origin was clearly key to taste (one wonders about Damianus's Ephesian fruit trees). Some New York Times food section-type judgments were made here: a Greek doctor of the age, Galen, can comment in passing that the best plums are from Damascus in Syria, for second best, try Spain. Eastern cities were also imbricated in the trade networks that extended between China, India, and Rome, routes along which luxuries such as silk and pepper flowed (seen, for example, in the discovery—from a site along the Red Sea coast—of a storage jar containing 7.5 kg of black peppercorns: the equivalent of about 140 of those little McCormick spice jars we buy).

Now the imperial capital of Rome is the point, the end point, the terminus of this global trading activity. But the cities, and the civic elites, of the east unquestionably formed links along this chain. One dramatic, if ironic, testament to the riches then available in the great eastern cities comes from the Book of Revelation, chapter 18, in a prophecy of a wanton city's destruction (a wanton city possibly modeled, incidentally, on Damianus's home town of Ephesus). To paraphrase the ranting, the merchants of the world will weep and mourn because the city will no longer consume "cargoes of gold and silver, jewels and pearls, cloths of purple and scarlet, cinnamon and spice, incense, perfumes and frankincense; wine, oil, flour and wheat, sheep and cattle, horses, chariots, slaves, and the souls of men. . . ."

It can safely be assumed that a wider range of foodstuffs, a more expansive cuisine, would be available in the world of Damianus, and that such differentiation served—as it did in Rome—to separate elite taste from that of the broader population. What is piquant, however, is the relative silence about such delectables in much of the Greek literature of the period. Take Plutarch—a well-networked Greek notable, priest at Delphi, Roman citizen. Plutarch wrote several books of Quaestiones Convivales (or Table Talk as it is usually translated), a series of dialogues presenting issues suitable for dining conversation and the forging of commensality. One of the more striking things about this work is the lack of interest in what was actually on the table. The odd wild boar or interesting fish might be briefly admired, but the meat lies in what follows—the conversation, the fellowship. In this Plutarch follows one of his principal models, Plato's Symposium, which (as Plutarch testily points out) is hardly first and foremost about stuffing your face. Now texts such as these, of course, are a controlled sphere of representation which shapes, but does not directly illustrate reality. It is unlikely in the extreme that Damianus and his ilk (Plutarch and his friends) were not partaking of a more elegant, opulent cuisine, not using food as a status marker, as a sign of wealth and distinction. But literary treatments suggest something of a cultural ambiguity about this culinary expansion and refinement: a hesitation perhaps in part reflecting past traditions, perhaps in part rejecting the notion that the Greeks too "eat the world."

Next question: with whom would Damianus eat?

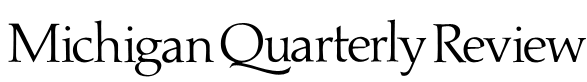

Reading Table Talk and other texts of the period, a far-flung elite community of dining promptly emerges. If you were a member, no worries! Visit a city, hit a major religious festival, go to a spa: someone will invite you to dinner—in the full expectation you stump up when what goes around, comes around (Figure 2). This club clearly extended to Italy, Rome, and beyond; it embraced Greeks (some of whom possessed Roman citizenship) and Roman citizens. Plutarch's dialogues, written in the early second century ad, present scenes of calm and mutually respectful interaction. Yet there are other stories, especially from the earlier years of contact. For example, the elder Seneca recounts a wince-making story of Cicero's son, Marcus (we are now talking of the late first century bc). Attending a dinner party as governor of Asia, Marcus got plastered, and kept asking and forgetting (as one does) the name of the person at the end of the table (as it turns out, a notable sophist from Smyrna). An attendant slave kept whispering the name, to no avail—until in desperation, he told Marcus "that's the man who criticized your father." That sank in, and the sophist was whipped—apparently while still at table.

We can hope that was not the norm, but there must have been an increasing presence of foreigners at Greek tables, and this need not have been instantly easy—anthropological studies of foodways warn that bad things can happen when different modes of power eating clash. One major disjuncture between Greek and Roman dining is similarly revealed through a misunderstanding: in this case about the gender of just who's coming to dinner. In one of Cicero's Verrine orations, we are told that Verres and his posse are invited to the house of a prominent citizen of the Greek city of Lampsacus, in northwest Asia Minor. The party goes well, so after a bit they decide to drink "in the Greek fashion." It is not exactly clear what this means, but it probably ratchets up the booze level (the big drinking cups come out). Eventually the Romans ask for the daughter of the house to come in, but her father says no ("it is not the custom of the Greeks that women should recline at the convivium of men"). The matter ends in a brawl, a dead Roman, and the ultimate execution of the Greek host and his son.

The disagreement here revolves, at least overtly, around a frequently cross-culturally vexed issue—the presence of respectable women at table. In pre-Roman Greece, this appears to be a fixed and final no-no (unless the guests were family). Only "bad girls"attended the classical symposium. The Roman situation is not entirely clear, but it is usually accepted that—by the early empire—such women could, without prejudice, attend and even recline at Roman dinner parties, at convivia. So what about the Roman east? It is certainly apparent that the role and representation of citizen women was altering within the framework of empire. Women now served as public benefactors; their names appear in inscriptions; statues are erected in their honor; Damianus dedicates a building in his wife's name (and then a bigger one in his own!). Provincial women of the upper classes enacted far more active, public roles, though it is equally clear they are recognized principally as the female elements (the wives, the mothers) in the male-led elite community, honored not least as marriage partners to weave and bind that community together.

So—by the second century ad—would Damianus's well-born wife eat with him, in company drawn from outside her immediate family? Intriguingly enough, the answer remains opaque. A new colleague here at Michigan, Lisa Nevett, has recently examined Roman-period houses in Greece; she argues that a lot of the uptightness of classical housing (which made a fetish of hiding women away) began, at this time, to loosen. I won't go into details, but the change is a matter of greater visibility into the house, and of more shared use of an increasingly decorative internal space. While the data base remains lamentably poor, it nonetheless begins to point toward significant change in the organization of households under the empire. But this still does not directly speak to dining. As for literary representations, if Plutarch (for one) doesn't forbid his wife to know his friends, neither does he systematically write her presence into the ideal gatherings of the Table Talk, his version of what dining is for, and how it should work. How far this hesitation and reluctance—this adherence to a past ideal—was genuinely operative is difficult to know. Yet these texts reveal (again) a less than direct, or untrammelled, buying in to Roman modes and mores.

And finally—how, in what setting, would Damianus dine?

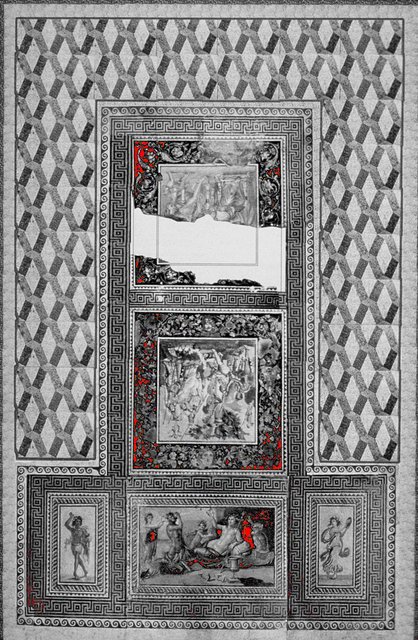

Quite likely in something like what is reproduced in Figure 3, a reconstruction (from a recent excellent museum exhibit) of the dining room of the "Atrium House" at Antioch. One must imagine diners lying on couches around the three sides of this open-ended U, with mosaics in the middle (where a table would be placed) and in front. Views would extend out into a nice courtyard: perhaps to a garden, to statues, often to water features such as fountains.

The thing is—as a comparison with Figure 2 reveals—this is a very Roman-looking dining room or what we call a triclinium, after the three klinai, the three couches for reclining (a habit, just to complicate things, originally borrowed from the east). Figure 2 also depicts slaves fetching and carrying (and one would need slaves, this is not a set-up designed for leaping up to check the roast). I won't deal with previous styles of the Greek dining room—the classical andron, the Hellenistic oecus—but (apart from the shared element of reclining), neither looks like this. Tricilinia of this form appear all over the eastern provinces, as elsewhere in the empire, at least from the second century ad onwards (what happens in the decades before that remains very unclear). And students of this kind of thing have accepted, without much debate, that what we see here reflects a simple adoption of the Roman mode of dining in the east.

There is more to the dining space than its shape, however. It is very clear that in Italy, in Rome, certain protocols accompanied the form, not least a very strong hierarchy to the experience. This is a subject on which John D'Arms wrote with sensitivity and power—his article on the vulnerable role of slaves at the Roman convivium is one of the few things I've seen reduce Michigan undergraduates to gulps. A key to this hierarchy is the seating plan, with a very clear place of honor next to the host—thus creating a kind of "power corner" privileged with the best views over and out of the room. Every other place at table was graded lower in status, increasingly below the salt. Games of honor and humiliation were played out in conversation as well (with some people not spoken to, nor welcome to speak—the junior faculty phenomenon!); some were visibly given worse food, or less wine, than others. Lying on a couch huddled next to a neighbor, such inequities would be hard to miss—no one ever said the Romans were subtle! All in all, a convivium could be (for some) a pleasant, convivial occasion; for others, the dinner party from hell. In essence, this is all about dinner as hierarchy, as rule making, dinner as creating social alliance and distance, dinner as a diacritical feast.

How far does such behavior accompany the triclinium form to the east? The "place of honor" certainly seems to have been adopted at least in some contexts. We see this in the careful organization of views from power corners; a defined best place to lie and look emerges in some examples of eastern triclinia. And Plutarch in Table Talk makes it very clear that the Roman place of honor (which is different from its Greek classical predecessor) was well in use in his day (indeed he provides just about our best discussion of the phenomenon). Another dialogue in Table Talk raises the question whether or not one should always assign seating at dinner. This particular debate was set off by an unfortunate episode: Plutarch recounts that a foreigner (a xenos) showed up at one of his parties, saw no suitable place saved for him, and stormed noisily off. Some in the dialogue laughed it off, others were clearly more anxious: fuss can lead to public trouble. The discussion almost immediately proceeds into admiration of a man who really knew how to throw a party, a man who could "organize infantry divisions to be as terrifying and dinner parties to be as agreeable as possible." This man was Aemilius Paullus, a Roman general who once celebrated a triumph for victories over Greeks and who erected a massive victory monument at the panhellenic sanctuary of Delphi. Military analogies, which recur throughout the Table Talk, quietly suggest that "dining in good order" was something Roman guests, and rulers, expected to happen.

That's a slightly paranoid view of the dining change (though sometimes there is nothing wrong with paranoia). I can offer another, not mutually exclusive explanation for this general development. My suspicion is that dinner was simply too essential an arena for the Greek elite either to dodge or to do its own thing in too radical a fashion. In imperial society, dinners served as a central way to meet and deal with peers (Roman and Greek) in an invite-only space, with a shared sense of status membership, of elite rules and understanding, of defined social competition. And this wasn't only useful at home. Proper understanding of the rules of the triclinium provided you with a behavior set with which you could travel the length of the empire and never put a foot wrong. In an imperial world where St. Paul, Pausanias, and the emperor Hadrian are only three of the more famous travelers, such shared understanding would be no minor desire. A very funny piece by the second- century Greek author Lucian illustrates the perils of the socially naive in such a world. His On Salaried Posts tells of a Greek philosopher who hopes for a position in a Roman household (to give the place some culture); he is invited to dinner, given a place of honor, but is clueless about how to act—the "what do you do with the cherry pits at an Oxford college high table" kind of story, and it ends in tears.

Lucian's philosopher may have been a loser, but Damianus and his peers were not. Their adoption of triclinia, I would argue, contributes to something we see developing more generally in the early Roman empire—and that is the creation and increasing definition of a supra-local, pan-imperial elite, a web of connections very separate from hoi polloi. This is what we see in the composition of Plutarch's dinner parties, in the intermarriages of elite families, in the fact that Damianus and his cohort—if not necessarily his wife and daughters—would eat in this new imperial format. A simple point to underline here is that dining practices worked to perform and to establish social alignments and divisions very different from accepted pre-imperial norms. Dining was not epiphenomenal, but a force for change in the Roman east.

Time, however, to drop the other shoe. So far this pattern of adoption fits the "smooth cooptation" model of provincial elites. What about those fundamental tensions in the Greek/Roman relationship? What about the hesitancy seen in the embrace of luxury foods and women at table? Was this new ritual of dinner truly swallowed by the Greeks hook, line, and sinker? We can, I think, see some hints of a different spin to these occasions, hints which suggest that—while Greek elites do indeed eat differently from before—they do it, to a degree, on their own terms.

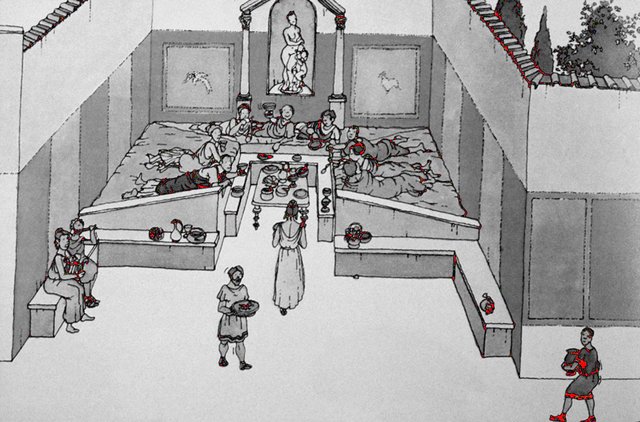

The only thing I have time to get into briefly is their decorative choices: the images selected to adorn these spaces, to stimulate the thoughts, conversations, and memories of those invited to dine. Elsewhere in the empire—Italy, North Africa, France, Spain—dining rooms were frequently decorated with scenes of civic spectacles, especially of the games, the arena. Gladiators, or more frequently animal fights, animals eating people, all in the comfort of your own dining room. Such images (which are still jaw-dropping, thank heavens, to us) laid claim to political authority and community standing: the host is revealed as the admirable and desirable kind of person who paid for such games, and who advertised that fact in his triclinium's "tournament of value."

We find some of these motifs in the east (including a gruesome favorite, from Cyprus, where a leopard walks away from a wild ass—with the ass's head in its mouth). But we find them much less frequently than elsewhere and never (as far as I know, anyway), never specifically in a triclinium setting. What we seem to find instead is a preference for scenes of local mythic interest and for themes of philosophy and sophrosyne (self-control). We can examine this through one remarkable example: the reunited floor mosaic ensemble of the triclinium, again from the Atrium House at Antioch (Figure 4; one part of the floor is in Paris, the other in Worcester, Massachusetts). Couches, again, would fill the U marked by the geometric pattern. As one entered, you would first see Herakles and Dionysus having a drinking contest (with the mortal getting the worse of it). Next came a Judgement of Paris, an event believed to have happened nearby (thus constituting a major civic claim to fame), followed by a (partially missing) representation of Aphrodite and her boyfriend Adonis—another local hero. This emphasis on pushing local myths and the local past is obviously akin to what we noted earlier about Greek nostalgia and its possible uses. And these myths also address themes common to the Greek literature of the period: themes of honor, the limits of mortality, the choice between pleasure and virtue (seen here in bad, warning examples: Herakles passes out; Adonis disobeys his divine mistress and perishes; Paris, judging the goddesses, starts a very big war).

In other words, the motifs selected here address a set of themes that were not necessarily designed to travel everywhere, but that chart an alternative, more specifically Greek, channel of self-definition and mutual validation. These mosaics (and others like them) suggest that the dining experience in the Greek east, and of an individual like Damianus, would be no straightforward, effortless copycat of Rome.

To sum up: posing these questions about Damianus and his eating habits has revealed significant changes in dining practices in the eastern Roman empire: in what was consumed, in what company, and just precisely how. Yet these changes seem far from a "falling in line" or a slavish adoption; rather they appear a dialogue and a negotiation—there are points of resistance and outright anxiety. In this sense, power lunches in the Roman east reveal a great deal about elite power, and vulnerability, in this particular part of the empire, about particular reactions and conclusions about what to do, how to eat. Clearly, we are right to reject any conviction that there was a single "Roman" way to dine.

Beyond that observation, I would add that I have always been struck by how past scholarship has tended to deal with the Greeks under Roman rule. I've already alluded to the parallel dismissal of "Old Europe" in rivalry with a robust superpower; the Greek/Roman nexus has also been taken as echoing the "special relationship" of the United States and the United Kingdom (the tangled emotions of a brash military power and its cultured predecessor). I get the same frisson from tainted praise such as "a talented people with a great civilization" (a recent George W. Bush verdict on the people of Iraq). It is very easy, as we know, to distance and stereotype a people less powerful than yourself, to lose sight of their struggles about how far to comply, and where to make a stand. Food, as John D'Arms well knew, offers a potent means of access to these decisions, and an intimate barometer of change. His recognition, that "food fights" were consequential, is consequential—his work continues to extend a challenge that all of us should heed.