Whither Exodus? Movies as Midrash

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Pleading for his love, Anne Baxter attempts to sway Charlton Heston from the path of righteousness. "You stubborn, splendid, adorable fool!" she calls him. Surely, she insists, rubbing up against him in her feline Egyptian fashion, the rustic Midianite wife of Moses has nothing like such white skin, soft lips, perfumed hair. But Charlton Heston is firm. Firm of mind, that is. "There is a beauty beyond the senses, Nefertiri," he informs her. Now she turns sullen. She alone, she tells him, can convince Pharaoh to let the Hebrews go. Or, she warns, she can persuade him not to. But Charlton Heston does not budge, no femme fatale can move him. And so, Nefertiri, with her cunning wiles, hardens Yul Brynner's heart.

So goes Cecil B. De Mille's The Ten Commandments. And here is Exodus 4.21: "And the Lord said to Moses, 'When thou goest to return into Egypt, see that thou do all those wonders before Pharaoh, which I have put in thine hand: but I will harden his heart, that he shall not let the people go.'" What has happened to the Bible's insistence that it is God who hardens Pharaoh's heart all through the story of the plagues?

In Dreamworks's 1998 animated film The Prince of Egypt, the youthful prince Moses is told his true identity by his sister Miriam, after stumbling into his natal family in a back street. He haughtily rejects her eager welcoming him as the "deliverer," but as he rushes away she sings a lullaby we have heard in the first reel, and we see something stir in him. Back home in the palace, he dreams, or hallucinates, a scene of firstborn babies being thrown into the river by Egyptian soldiers, and wakes to a wall painting that shows exactly this. Soon afterward, horrified by the evils of slavery, he accidentally kills an overseer in the middle of a crowd, while trying to stop him from beating an old man. His half-brother Rameses reassures him that he won't be punished, but he is racked by guilt. Exclaiming "All I've ever known to be truth is a lie!" he runs away, into the desert.

What has happened, in this film, to the Moses of Exodus, who kills the overseer on the sly and runs away from Egypt because he realizes his crime is known? ("He looked this way and that way, and when he saw that there was no man, he slew the Egyptian and hid him in the sand . . . when he went out the second day, two men of the Hebrews strove together, and he said to him that did the wrong, Wherefore smitest thou thy brother? And he said, who made thee a prince and a judge over us? Intendest thou to kill me, as thou killdst the Egyptian?" Obviously this is not a bit of Scripture suitable to Hollywood.) What has happened to the Moses whose identity is revealed to him not by a sweet-face sister but by a burning bush?

As with screen adaptations of novels one has loved, it is easy to be shocked, shocked, at omissions and deviations in Biblical epics from the original sacred text. But suppose we think about De Mille's The Ten Commandments and Dreamworks's The Prince of Egypt in terms of a Jewish genre whose essence is sacred play with sacred text for the sake of communal need—the genre of midrash.

Describing the medieval rabbinic tradition of midrashic storytelling, the scholar Gerald Bruns argues that efforts to reconstruct "original meaning" in biblical studies necessarily fail, because Scripture is itself future-oriented. "The bible always addresses itself to the time of interpretation; one cannot understand it except by appropriating it." "Midrashic understanding," says Bruns, means that we "take the text in relation to ourselves, understanding ourselves in its light, even as our situation throws its light upon the text, allowing it to disclose itself differently, perhaps in unheard-of ways." Rabbinic midrash is full of "excessiveness . . . legendary extravagance . . . always seems to be going too far, saying what the text does not say but also what the text, taken by itself, does not seem to warrant," because it is a two-way "dialogue of text and history" in which text is always being adapted to and by a community that is ongoing in time, and which is always itself being shaped by the text. When the rabbis re-tell Scripture with "parables, sayings, puns, stories" and flights of imagination designed to fill in its gaps, reconcile its contradictions, locate its meaning in the time of the listener, it is also understood that a single text may yield multiple meanings. "There is always another interpretation," say the rabbis.

An example: All little Jewish kids who go to Hebrew school learn the story that Abraham's father, Terah, was an idol-maker, and that the young Abraham tried to convert him to monotheism. One day Abraham broke all the idols in his father's shop except one, and put a stick in that one's hand. When his angry father demanded to know who was responsible for this vandalism, and Abraham pointed to the big idol, the father angrily cried, "that cannot be! It is only wood!" Thus Abraham proved to his father that idols were not gods, and the father was converted. I have met many Jews who think this story is in the Bible. It isn't, it's just midrash. But the point is that Jews apparently need an Abraham who is already an iconoclast to be chosen by God as the first patriarch. Another example: In Genesis 18 when God and two angels visit Abraham in his tent at Mamre, the patriarch makes them a meal of a calf, and butter, and milk—but this is a scandal, it isn't kosher!—and for the rabbis it didn't matter that the laws of kashrut don't come along for hundreds of years later, so in the midrash, there's a three-hour wait between the meat and the milk. Yet another instance: when the prophetess Miriam dies during the wandering in the wilderness, the next thing that happens in the Book of Numbers is a drought. To the ordinary reader, the two events might not be connected, but for the rabbis everything in Torah is connected with everything else. God weaves a tight web, and nothing escapes. So according to midrashic tradition, God made Miriam's Well during the first week of creation, in preparation for the exodus. The well followed Miriam underground wherever she went, spouted forth wherever she stopped, and dried up when she died.

It so happens that the making of movies is an extravagantly collective activity, not unlike the authoring of scriptural texts. Here is another proposition: the Biblical interpretations of Hollywood epics are appropriate acts of appropriation that are essentially midrashic. Their intention and effect is to make the stories both awesome and morally meaningful to their audiences, to give the audiences the spiritual spin they need. So what was needed by Americans in 1956 when De Mille's The Ten Commandments with its then unheard-of cost of thirteen million dollars, its cast of 12,000 extras and 15,000 animals, and its credit list of thousands, became one of the all-time top-grossing movies ever? And what was needed by Americans in 1998 when Dreamworks made The Prince of Egypt, which was also a box-office hit and which whole congregations even today view with their children?

Two contexts are relevant. For The Ten Commandments we have to remember the period of the Cold War, the Eisenhower and Joe McCarthy fifties, with its clearcut views of good and evil and its even clearer gender roles. For The Prince of Egypt the post-Cold War zeitgeist, with its multiculturalism, moral relativism, and gender-bendings, is the key.

The two movies share some features. De Mille solemnly appears before a theater curtain at the outset of The Ten Commandments announcing the anti-Communist message of the day that this is "the story of the birth of freedom. . . . Are men the property of the State, or are they free souls under God?" The Prince of Egypt similarly begins with a scrolled text telling us that the movie is "true to the essence, values and integrity of a story that is still a cornerstone of faith for millions of people worldwide." We are instructed, in both cases, that these movies are not mere entertainment. Both involved massive research and expert assistance in producing "authenticity." The first century philosopher Philo's view of Moses as a man whose innate high principles enabled him to resist the temptations of the Pharaonic court, and the renowned archeologist James Breasted's theory that Moses and the future pharaoh Rameses grew up as brothers, govern both films. (Breasted's contribution is crucial because it makes the story a family drama, something Americans will understand.) And of course both movies are spectaculars, overflowing with Technicolor miracles—the burning bush, the plagues, the parting of the Red Sea. Both are visually awesome in depicting the monumentality of Egypt and visually sensational in depicting the cruelty of slavery. To thicken the plot a little, The Prince of Egypt is partly a visual midrash on The Ten Commandments: Dreamworks's Rameses looks quite a lot like Yul Brynner, and one of Pharaoh's High Priests looks rather like the baddie Edward G. Robinson. And both pictures might be seen as midrashically borrowing the theme of fraternal rivalry from the tales of Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau.

But the differences are as interesting as the parallels.

The Ten Commandments is a product and reflection of an era in which America's moral superiority to the Soviet Union consisted in a fusion of piety and patriotism. The piety of De Mille's Cold War version of the Old Testament has a kind of white-bread Protestant aura that lets Moses return from his burning bush experience intoning ". . . And the Word was God . . . he is not flesh but spirit . . . the light of Eternal Mind. . . . His light is in every man," rather a shift from the thoroughly tribal God in the Biblical burning bush episode, but that's the point. Everyone in the movie is white except for some exotic Ethiopian captives—and Yul Brynner's slightly Asian look, charismatic and sinister, as the sneering and evil Rameses.

And then there is the patriotism. Gilles Deleuze sees the use of history in American cinema as "deeply analogical" to American history. Historical films have the task of disclosing

Michael Wood has pointed out more specifically that American biblical spectaculars replay the American Revolution, with the oppressive ruling class identified with Britain (elder and younger Pharaohs in The Ten Commandments both have British accents), and oppressed but triumphant Israelites as the Americans. Wood is the first to have seen the final shot of Charlton Heston as a sort of Statue of Liberty. He also points out the motif of the Attractive Oppressor, a sign of American anxiety about its cultural inferiority to the Old World. To make Ancient Judaism a "prototype of the democratic state" may seem a little silly to anyone who knows anything about ancient history, but we remember that in the myth America has told about itself, from the Puritan Fathers to the present, America is the promised land, the escape from idolatry and injustice. The story of Exodus was the master narrative for the Pilgrims. Moreover, for De Mille's zealous anti-Communism, Egypt is the Evil Empire personified, atheistic as well as oppressive (the priests are charlatans). True to McCarthy Era paranoia, Edward G. Robinson's Dathan represents the Enemy Within, trying to corrupt the Israelite nation with godless materialism and licentiousness. It is Dathan who is responsible for the Golden Calf and the orgy that follows it, embodying the identification of Communism with the evils of Free Love.

Which brings us to the immense importance of sexuality and femaleness in The Ten Commandments. The heavy-handed morality of his movies is what, as all commentators agree, made it possible for De Mille to show an extravagant amount of skin, all in the cause of salvation. In The Ten Commandments we have the beefcake/ hairless upper torsos of Yul Brynner as Rameses and John Derek as Joshua, we have sexy-dancing-girl scenes performed by captured Ethiopians and Midianite maidens, we have gigglingly trivial handmaids of Pharaoh's daughter talking semi-dirty to each other, and above all, we have an orgy. "Law and orgy" is a winning formula for movie epic. What more do we need? Well, there are not one but two panting romantic subplots undreamt of in the Old Testament. The love triangle of Rameses, Moses, and Nefertiri conveniently supplies a motive for Rameses's stubbornness which exonerates God for hardening Pharaoh's heart. The woman was to blame! Then there is the gratuitous inverted triangle of Joshua, Dathan, and Lilia-the-slave-girl. One might visualize these two triangles as a Jewish star, and the sexuality of the whole movie as diluted Freud.

The primary tension in The Ten Commandments is between the hero and the anti-hero, Moses and Rameses, good guy and bad guy, played out as another psycho-pop stereotype of the 1950s, sibling rivalry, with perhaps an unresolved Oedipus complex lurking in Rameses's need to exceed his father's greatness. Four decades later, in The Prince of Egypt, this relationship looks entirely different. But it should be clear that in religious, political, and psychological terms, what we have here is precisely the dynamic described by Bruns: "midrash is a dialogue between text and history in which the task of giving an account . . . involves showing how the text still bears upon us, still speaks to us and exerts its claim upon us. . . . There is always a dialogue of text and history, in which the one is adapted to new situations and the other . . . is shaped by what the text has to say."

The animated film The Prince of Egypt, arriving in a post-Cold War, post-feminist, multi-cultural America, is a hymn to political correctness in a kinder, gentler version of ancient-Israel-as-prototype-America. Here, everybody has more or less dark skin, though Pharaoh still gets an English accent. The Semites actually look Semitic, and a few minutes into the film, following the first shots of cruel taskmasters, we hear Middle-Eastern sounding music, and the infant Moses's mother singing to her infant in Hebrew. Hebrew returns at the film's end as the Israelite nation sings "Micha Mocha" joyfully to its God. Lest the parallel of the Exodus with the liberation of American blacks be forgotten, we also hear Boyz II Men singing "I will get there" under the lengthy credits, and, at the very close, the screen provides quotes from the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Koran. Paul Robeson doing "Let My People Go" would have been too much to ask.

The treatment of women is interesting. Gone are the dancing girls and seductresses, gone is the orgy. Gone, in fact, is virtually all the heavyhanded and bosomy sexuality of the De Mille film. An obvious reason is that The Prince of Egypt is supposed to target kids—though I think something else is going on as well. And there is certainly a bid for what the Dreamworks fellows may think of as a women's lib audience. A rather graphic childbirth scene early in the film looks like a bow to Our Bodies, Ourselves, with Jochabed groaning, Miriam frightened, and the baby being delivered by his father. Later on, Miriam heroically insists on revealing Moses's true identity to him, despite his anger and brother Aaron's craven attempt to hush her. Miriam all during the episodes of the plagues and the departure from Egypt is an encouraging presence, faithful and wistful. In the scenes in Midian, Zipporah is wholesome but spirited. First she drops Moses down a well from which he is being rescued, then it is she who does the wooing when the plot calls for marriage. "Dance with me!" is her big musical number. When Moses declares his intention to go back to Egypt, Zipporah questions him about it, and ultimately announces, "I'm coming with you." When Moses goes to confront Rameses at court, his companion is Zipporah, not Aaron.

Many of my friends were ecstatic at the way the Dreamworks film "foregrounds" female characters. I'm a little skeptical here, frankly. There are missed opportunities for a Miriam who might have exercised her wits at the Nile—in Exodus she gets Pharaoh's daughter to hire Moses's own mother as a wet nurse—and her charismatic leadership of the dancing and singing women at the Red Sea, where the Bible calls her a Prophetess, is also missing. In addition, the visual depiction of Zipporah as wife is very very odd. She has these heavy eyebrows and seems perpetually frowning. Someone's idea of a Jewish Mother, perhaps.

The fact is that the great love interest of The Prince of Egypt is between Moses and Rameses. There's a complexity here that almost recalls Prince Hal and Falstaff. Here are two men attractive in utterly different ways, one supremely confident and always-already "chosen," mischievous at first, then taking on the responsibility to which he was born; the other amoral, proud, yet a figure of pathos, ultimately a loser, ultimately hollow. Of course Dreamworks's characters don't get the dialogue Shakespeare's do. And Dreamworks's Rameses is arrogant and sullen, unlike the exuberant Falstaff. And yet, and yet.

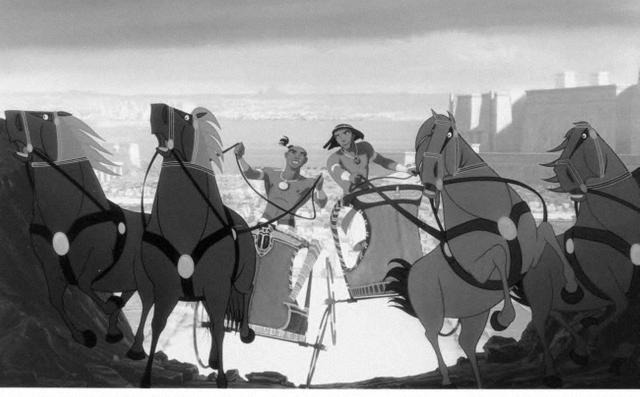

Competition and banter, outrageous play between Moses and Ramses dominate the early parts of The Prince of Egypt. The representation of their relationship begins abruptly, immediately after the adoption-of-baby-Moses scene. We cut to a headlong chariot race, the two laughing youths speeding recklessly around a construction site, scattering workers, cutting each other off, destroying some immense scaffolding. There is a moment when Rameses takes a higher path than Moses, and shouts down to him, "Come on, Moses, admit it, you always looked up to me." "Yes, but it's not much of a view," Moses shouts back, at just the moment we see Rameses' toga (or whatever the Egyptian equivalent is) flit up, showing his cute buttocks. The love between the youths is clear both before and after their division. When Moses returns to Egypt on God's orders, Rameses is thrilled to see him and they embrace with joy, until Moses explains his mission. All through the episodes of the plagues, both men are deeply troubled. "Why can't things be the way they were before?" Rameses pleads. Moses sighs frequently. He sadly returns a ring Rameses gave him. They sing a tormented duet. M: "All this pain and devastation, how it tortures me." R: "You who I called brother, How could you have come to hate me so?" Attempts at reconciliation fail. Moses weeps at the death of Rameses's firstborn. After the great scene of the Hebrews crossing the Red Sea and the Egyptian Army being drowned in it, we see Rameses isolated on a rock where he has been cast, crying "Moses!" and Moses, as if he hears this plaintive call, gazes into the distance and whispers "Goodbye, brother."

This quite amazing interpretation of the Moses-Pharaoh relationship encodes most obviously a wistful support of the peace efforts between Jews and Arabs, Israel and Palestine, which at the time of the film were looking hopeful because of the Oslo Accords. Only slightly less obviously, it encodes a homoerotic motif, which has been a thread running through American fiction and film ever since Huckleberry Finn. As befits an era in which homosexuality struggles to be accepted as normal, and homosexual writing often stresses the intense bonds of affection between lovers, as well as the tragedy of doom and loss, the veil is very thin.

Does all of this completely distort what the Bible means to tell us about Israel and Egypt? There is a rabbinic midrash in which, when the Egyptian army is drowned and the Israelites sing a victory song, the angels begin to sing triumphantly also, and are rebuked by God, who reminds them that these are his children also, made in his image. In many Jewish households it is the custom, when the plagues are recited during the Passover seder, to flick a drop of wine onto one's plate for each plague, in token of sorrow for the suffering of our enemies. Homoeroticism of course is another matter, but then again, what about David and Jonathan?

Finally, suppose we return to the whole topic of Biblical epic as spectacular, as dazzling to the sight, as representing "vision." Ilana Pardes, in an acute essay on the populism of De Mille's The Ten Commandments, reminds us that the sequences of miracles performed by God in the Exodus story—rods turning to snakes, rivers turning to blood, pillars of fire, seas parting—add up to carnivalesque "great wonders" which in the Bible and throughout Jewish tradition are a keystone of God's relationship to the whole people. "His illusionist art reminds us that a miracle is a spectacle, a magnificent show that cannot but astonish as it explodes the fixed boundaries between high and low, between dream and reality." Like God, Hollywood is a source of wonders, as awesome as they are accessible to all. Critics may joke about this: for example, James Thurber saying The Ten Commandments shows "what God could've done if he'd had the money." But let me take this an absurd step forward. Maybe the joking reveals the anxiety of the secular intellectual, not about Hollywood but about God, miracles, faith. We are uncomfortable when a movie comes too close to tapping some primitive and naive openness to religious awe, which we feel it is our business as secular intellectuals to resist and reject. "There can be miracles if you believe," Miriam sings earnestly in The Prince of Egypt, and I for one squirm at the mawkishness of it all. But in another part of my mind I remember that the artist has always made claims on the divine. Orpheus receives his lyre from Apollo, the prophet is the trumpet of God, and Coleridge in the Biographia Literaria announces that he holds the "primary imagination" of the poet as "the living power and prime agent of all human perception, and as the repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM." Why should not De Mille and Dreamworks join these ranks?

REFERENCES

Babington, Bruce, and Peter William Evans, Biblical Epics: Sacred Narrative in the Hollywood Cinema. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1993.

Bruns, Gerald, "Midrash and Allegory: the Beginning of Scriptural Interpretation," The Bible as Literature, eds. Robert Alter and Frank Kermode. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987, 625-646.

Gerald E. Forshey, American Religious and Biblical Spectaculars. Media and Society Series. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1992.

Kreitzer, Larry, The Old Testament in Fiction and Film: On Reversing the Hermeneutical Flow. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1994.

Pardes, Ilana, "Moses Goes Down to Hollywood: Miracles and Special Effects," Semeia 74 (1996), 15-31.

Wood, Michael, America in the Movies. New York: Basic Books, 1974.