Across the Maelstrom

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Lofoten Islands, Norway

They call it the Lofoten Wall, this island chain that seems to rise up sheer and black out of the Norwegian Sea, frosted with white in winter, emerald green in summer, jagged-spined as a prehistoric beast. I braced myself against the railing of the top deck of the coastal steamer, with the wet wind hard on my face. To the southwest are some of the oldest rocks on earth, remnants of a three-billion-year-old plateau. Faintly, through sea spray, I caught a glimpse of the most remote islands of the chain, Vaer¿y and R¿st. In January, 1432, a Venetian nobleman and his companions had to abandon their ship for small boats on a voyage to Flanders; they drifted helplessly north toward the Arctic until they washed up on a rocky islet just off of R¿st. It's from the elegant merchant Pietro Querini that we have some of our first descriptions of sea-girt life on the island near what he called Calo Mundi, the edge of the world: The men of the islands are the most flawless individuals one can imagine; they have handsome appearances and their women, too, are beautiful. Querini was fascinated by their custom of drying fish and took great rations of this stoccafisso norvegese back to Venice on the return voyage.

But long before then, this northern sea was known to voyagers and cartographers. The Greeks mentioned a people, the Hyperboreans, who lived beyond the rule of Boreas, god of the North wind. The geographer Pytheas made a journey northwards around 350 BC. Only fragments remain of his lost book, On the Ocean, including mention of an island called Thule. Stories, some true, most fantastic, of the north fired the imagination of cartographers. For some time I've had on my wall at home a reproduction of the Carta Marina, the first printed map of the Nordic Countries, which appeared in Venice in 1539. It was the work of Olaus Magnus, a Swedish bishop who'd never seen the coast of Norway or the sea, but who populated the waters of the north with serpents and monsters, aquatic versions of Sendak's Wild Things, munching on schooners.

I shivered in the water-logged wind. It was eight in the evening, July, and freezing cold. The sun was hidden in a bank of fog. In a day or two, I'd be heading for the far southwestern tip of the black sea-bulwark, to a village called Å. Pronounced "Oh," Å was the center of the Lofoten fishing culture for a few centuries, and the whole village had been turned into a museum. But what I was traveling to see—to enter, to cross, if I could—were the ocean currents south of Å. For that's where the legendary Moskstraum rumbled, better known in world literature as the demonic whirlpool of Edgar Allan Poe's story, "Descent into the Maelstrom." The navel of the world, the vortex, the sea-cauldron, the roaring kettle. In the Carta Marina, Olaus Magnus drew the Lofoten chain close to land and the size of a single pea, but there's no mistaking the circular swirl of the great vortex near it. An even better illustration comes from Magnus's history of the Nordic people which was published in Rome in 1555. In a map from that volume, the currents come together like hair curled tightly at the ends. The curls form a circle and within this circle is a ship. Other ships are half visible and sinking in the outer strands. "Maelstrom"comes from an account by mariners from Friesland, who named it, in their language, from maalen, to grind, and strom, a current. Now, of course, the word evokes turbulence of all kinds, especially a life going haywire.

I'd been on the track of whirlpools, real and mythic, in the North Atlantic for some weeks. Some of the most impressive are in the British Isles, the sea cauldrons of Celtic legend. In Gaelic these cauldrons are called coire, and one of the most famous of them lies not far from Iona and Mull in the Hebrides, between the lightly inhabited islands of Scarba and Jura. There, the Atlantic tide comes and goes so quickly and voluminously that the narrow gap between the islands becomes a watery conflagration of currents, creating waves that slap up twenty feet tall. It's called Corryvrecken or coire breckan, the cauldron of the plaid.

This tub of violence is where the great winter hag Cailleach was said to wash her cloak. When storms came on, especially in autumn, people told each other, "The Cailleach will tramp her blankets tonight." She washed her plaid and when she drew it up it was white and the hills were covered with snow. They used to say that, before a good washing, the roar of the coming tempest was heard by people on the coast for a distance of twenty miles. It took three days for the cauldron to boil.

There's another sea cauldron or coire off the northern coast of Scotland in the Pentland Firth. The Swelchie, which comes from the Norse word for whirlpool, svelgr, creates a whiplash water maze, a boiling circle amidst the currents rushing back and forth through the narrow body of water that separates Scotland and the Orkney Islands. There is a legend attached to the Swelchie, a legend more influenced by Norse mythology than Celtic. Two giantesses, Finnie Grotti and Minnie Grotti, were enslaved by a Danish king called Frodi. He kept them endlessly at work turning a magic quernstone called Grotti, which had the power to grind out anything it was asked to grind. At first Finnie and Minnie ground out a steady stream of peace and happiness, but then King Frodi demanded gold and more of it. Eventually Finnie and Minnie had enough and decided to grind out an army instead which would enable them to free themselves from Frodi's tyranny. There are two versions of what happened next, but both have the same result. In one the king was killed and Finnie and Minnie sailed off with a sea-rover called Mysing. While sailing through the Pentland Firth, Mysing asked the giantesses to grind out some salt. Since they were used to grinding in quantity, the salt soon overflowed the ship and sank it near the island of Stroma. The magic quernstone plummeted to the bottom and continued to churn. It created the whirlpool Swelchie, which is the source of all the salt in the sea. In an alternate version, it was the sea king Mysing who stole Grotti from Finnie and Minnie after Frodi was defeated in battle. He sailed off with it through the Firth, and thought some salt would be a good idea. Unfortunately, he couldn't figure out how to turn the quernstone off, with the same result as above. The ship sank and Grotti kept grinding.

Long before the folktale was told in Orkney as "The Magic Quernstone" or "How the Sea Became Salt," the thirteenth century Icelandic writer Snorri Sturleson, in the Poetic Edda, describes a whirlpool: "T'is said, sang Snaebjorn, that far out, off yonder ness, the Nine Maids of the Island Mill stir amain the host-cruel skerry quern—they who in ages past ground Hamlet's meal." Snorri tells the story of King Frohdi, the owner of a giant mill he couldn't turn, and two giant bondswomen Fenja and Menja from Sweden whom he found to work it for him. He drove them relentlessly, allowing only time for one of the giantesses to sing her song. Some scholars believe Menja's song to be the oldest surviving example of Old Norse literature. She tells her story, mourning her and her sister's fall from power to slavery:

The story of the millstone appears also in Saxo Grammaticus's History of the Danes which drew on Icelandic literature. Here it is the Nine Daughters of Aegir, the Ocean God, who grind out the meal of Prince Hamlet. "They set the ocean in motion as if a quern were turned round and they crushed out life between the stones. Far out, beyond the skirts of earth, the Nine Maidens of the Island-Mill stir amain the most cruel skerry-quern."

As far back as the Odyssey there have been stories of giantesses who turn a millstone under duress. Whirlpools were once called the navels of the sea, and the drowning of the millstone has been given a dozen mythic meanings. A less mythic, but equally poetic description of a whirlpool comes from the Sailing Directions for the Northwest and North Coasts of Norway, as quoted by Rachel Carson in The Sea Around Us: "As the strength of the tide increases, the sea becomes heavier and the current more irregular, forming extensive eddies. . . . These whirlpools are cavities in the form of an inverted bell, wide and rounded at the mouth and narrower toward the bottom. . . ."

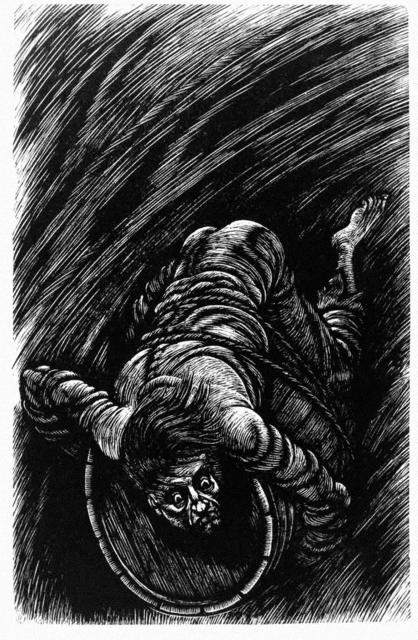

And of course there is Edgar Allan Poe, who made a literary career of the claustrophic and inevitable. In his story "Descent into the Maelstrom," he writes, in dreamy horror, of two brothers trapped in the relentless pull of the current: "How often we made the circuit of the belt it is impossible to say. We careered round and round for perhaps an hour, flying rather than floating, getting gradually more and more into the middle of the surge, and then nearer and nearer to its horrible inner edge."

So far on my travels, I'd only glimpsed whirlpools from afar. The previous day, disembarking from the coastal steamer in Bod¿, just above the Arctic Circle, I'd tried to visit the Saltstraum, an immense tidal current said to create huge whirlpools as it moved through a narrow strait thirty-five kilometers south of town. But I'd missed the bus that day; it was pouring anyway, and when I got to the Bod¿ tourist office, the brochure they pushed over the counter gave me pause. A modern building called Saltstraum Experience had been constructed along the banks of the strait; the brochure promised a "sophisticated multimedia show" and a souvenir shop. Warning, the brochure advised: The incredible forces that are at work in Saltstraumen, the world's strongest tidal current, make it perilous to cross by canoe or on small boats. All movement within the area, whether on sea or on land, is done at one's own risk.

"So there are no boat tours actually on the water, through the whirlpools?" I asked the woman at the desk.

"You must look at the water from the shore," she said severely. 'You can watch the movie in the multimedia center to get a closer view."

The Saltstraum Experience was apparently a virtual one, the imagery focused on sport fishing in the tidal confluences, a far cry from what I was after, which was more along the lines of Snaebjorn's poem—"The island-mill pours out the blood of the flood-goddess's sisters."

It had rained this morning, too, and I'd given up on the Saltstraum. I spent the morning in the Nordland Museum and at the library and got back on the coastal steamer at three to head across the Vestfjord. I didn't want to look at a whirlpool from a safe distance. I wanted to be inside it.

The Lofoten Islands are far north of Iceland, so I was astonished at the lushness of some of the cultivated gardens in the towns, as well as the abundance of blazing pink-purple fireweed against citrus-yellow grass in the fields and farms. Most of the places I'd been in the North Atlantic were so bare and wind-swept that it was a luxury to see emerald black firs and leek green lindens lining the sides of the roads. It's the Gulf Stream flowing up the Norwegian coast that creates a warmer marine climate and makes such vegetation possible hundreds of miles north of the Arctic Circle.

The younger mountains that make up most of the sixty-kilometer Lofoten range are very high peaks, sharply toothed, and were probably not covered by ice during the last Ice Age. The islands swing out from the body of Norway like a hinged door. Within the Vestfjord, a vast triangular marine basin formed by this westward swing, is—or was—one of the great fishing grounds of the planet. Every winter cod makes the long journey south from the Barents Sea to spawn off Lofoten's inner coast. Their eggs then flow back up north along the Norwegian coast on the Gulf Stream current to the Barents Sea; the larvae become mature fish after seven years and start swimming back to Lofoten. After that they return every year. For over a thousand years fishers came from the north and south of Norway to converge on the fishing villages of Lofoten. Romantic paintings of the eighteenth century and sepia-toned photographs of the nineteenth century show square-rigged, broad-beamed boats with heavy oars and brown sails filling the Vestfjord's snow-bitten waters in January every year. The old life continued into the twentieth century, even after the advent of motorized craft, and photographs show fishers in their shacks baiting long lines and sleeping tightly packed together in bunks.

Although today those shacks or rorbuer have been turned into tourist accommodations, and the fishing boats are technologically advanced, the winter cod are still dried in Lofoten the way they have been for a thousand years. Split in half, gutted, tails tied together, and slung over pine pole structures that are about thirty feet high, the fish dry slowly in the wind for four or five months before being removed, graded, and sold to Mediterranean countries and Africa. In Svolvaer, not far from an old wharf that now supports a hotel complex, were scores of fish racks. By now in July, all that remained on the oil-soaked pine poles tilted up in long teepees were a few bunches of cod heads with dry, cloudy eyes. They looked like translucent paper lanterns.

My bus ride south through the Lofoten Islands to Å took much of one afternoon. I leaned against the window and enjoyed the warmth of summer on my cheek. But by the time I arrived in Å around four, a cooler mist had descended, and my mood checking into the youth hostel was subdued, if not depressed. It was the only place to stay in Å aside from the high-priced rorbuer or converted fishermen's shacks, which in any case were full this evening. I'd stayed in youth hostels before on this trip, and never minded it, but somehow, as I climbed up steep loft stairs with my pack to a four-bunk room with a single light bulb, I felt out of place and about two hundred years old, especially since the rooms around me were taken by attractive young Italians in shiny black motorcycle gear.

There were a number of Italians in Å, and at first I was puzzled to find a tour bus group in the Stockfish Museum, listening to a Norwegian giving a lecture in Italian. Uncharacteristically for a northerner, the guide was animated, gesturing magnificently, welcoming the tourists to Å, reminding them that their countryman Pietro Querini was the first exporter of dried fish, thanking them for all their country's economic support of Norway for the last millennium. Could they guess what percentage of the dried cod from Lofoten went to Italy? "Ninety-five percent?" called a voice. No, not quite, but almost! Italy was the best customer for the prima grades of stoccafisso norvegese, especially Northern Italy, where the stockfish was graded into categories like Ragno, Westre magro 60/80 grand premier, Westre magro 50/60, Westre prima. . . .He held up different grades of dried fish as he spoke and the Italians, those who weren't standing outside the door of the museum smoking, looked on raptly. But my Italian wasn't good enough to understand the complicated ins and outs of the drying process, so I continued wandering around the two floors of the museum ("the only one of its kind in the World"), with my printed guide. I regarded hoisting baskets, gutting benches, liver and roe gauges, rinsing vats, wheelbarrows.

A strong smell of fish hung over the village, a charming collection of dull-red buildings clustered at the foot of jagged mountains. A hundred to a hundred and fifty years ago it had been a bustling fishing station, one of dozens along the coast of Lofoten. In those days, up to 25,000 fishers had come to the islands for the winter cod season. They slept three to a bed in the fishermen's cabins; the heating was meager; there was only scraped sealskin over one window for light. The buildings in Å included a blacksmith's shop, a bakery, a cod liver oil factory, warehouses, boathouses, a mercantile where spirits and equipment were sold. Unlike Kabelvåg to the north, which had functioned as a manor house, farm, and trading center, Å had been seasonally packed with men from the mainland coasts of Norway, who'd sailed across the Vestfjord and were hoping to make their fortunes in tough but rich fishing conditions.

I left the Stockfish Museum, somewhat depressed at the way the past is saved and served up again to tourists, and wandered around in a mist that turned into rain. I'd planned to stay here two nights, but I didn't know if I could handle it, especially since I'd discovered that my plan to cross the Maelstrom had fallen through. The boat that was supposed to go tomorrow had engine trouble, and another boat only departed on Mondays and Fridays. As the rain increased, I returned to the youth hostel. The room was still empty of anyone but me; I couldn't decide if this privacy was good or just lonely. All through the rest of the building, I heard Italians talking and laughing.

The next morning I woke to a sad summer downpour. I lay in my bunk in my sleeping sack, listening to the rain. You'd think, with all the Italians visiting Å, there would be an espresso bar. How I yearned for a steaming hot double latte. The sweet damp fish smell of the village seeped through the hostel and I thought, I must get out of here. From a payphone I called the local tourist office, and asked about accommodation in nearby Reine, a slightly larger village and, more importantly, a real place, not a museum, where I'd heard that it might also be possible to catch a boat going to the Maelstrom. "You won't find anything in Reine, not at this season," the young woman said firmly. "Far too popular." Undaunted or perhaps just desperate, I decided to call some places in Reine anyway. One of them said they had one rorbu left, for one night. It had two bedrooms, slept eight, and cost far too much. "I'll take it!" I said, justifying the extravagance by thinking how much money I'd saved in the youth hostel.

Reine's setting was just as spectacular as Å's, but less huddled, less pressed against the mountains. Or perhaps it was only that the sun came out as I left Å, so that Reine, twenty minutes away, immediately seemed more open and welcoming. A ring of black granite peaks lightly furred in green surrounded a harbor across which islands and peninsulas had been connected by bridges. The houses were dark red and yellow ochre with white trim, built on bare gray stone or on pilings over the water. When I checked into my room, or rather, my house, I found the view off the end of the wharf was of the harbor and the castellated dark granite mountains behind. The grizzled-gray clouds were breaking up, the sky was giddy azure behind them. The wharf was silent except for the murmur of a couple of maids walking by with buckets. I had a full kitchen, a bath, a huge sitting room with pine chairs and two sofas upholstered in plaid. I was tempted to spend the rest of the day with my feet up, reading, in this rorbu where probably twenty men had once slept in bunks.

But when I'd gotten off the bus in Reine, I'd noticed a small sign by the grocery store advertising boat trips to the cave paintings at Refsvika. "Our trip takes us over the waters of the famous Moskstraum," said the flyer. I called the mobile phone number, expecting excuses, rejection. The weather wouldn't be good enough, the sea would be too rough, the tour only went every other Thursday. . . .

"We leave at two o'clock," said the man. "An English couple is going also. And two Italians."

Sue and Mike were from the Midlands. In their fifties, they had the ruddy look of avid British ramblers and birders. Mike seemed ready for anything in jeans and much-worn green anorak, with camera and binoculars slung around his neck. Blond Sue smiled readily but had a very determined manner that suggested, Let's just get on with it, shall we? She was, like me, more interested in the literary aspects of the Maelstrom than the cave paintings of Refsvika.

"Poe makes it sound so absolutely fiendish that one can't help but be curious," she said, as we three struggled into our red flotation suits down by the dock where our rubberized raft waited for us. In case of the raft overturning or accidental immersion, said Jens, our guide, we'd have an extra thirty minutes in the water. Sue and I exchanged glances.

Jens said, "Don't worry. Everybody thinks they will fall in but nobody does fall in." He held up his mobile phone. "I will call for help if we capsize," he added off-handedly.

I felt as if I'd met a hundred Norwegian men like Jens over the years. Physically fearless, expressionless to the point of moroseness, with the faintest of ironic grins. The English phrase "a smile tugged at his lips" is "he pulled on the smile bands" in Norwegian. I thought of that phrase every time I looked at Jens. He was twenty-seven, the father of two, from a fishing family, of course. These raft trips were an extra source of income for him during the summer months.

The Italian couple appeared just as we'd finished suiting up. The young man was a medical student, tall, trim, bespectacled; I found it vaguely reassuring that he might be able to deal with hypothermia or resuscitation should it become necessary. His girlfriend had lustrous dark hair that fell in waves around an unenthusiastic, Roman-nosed face; she had on one of those short, tight, wool sweaters that only Italians and Spaniards seem to wear, year after year, oblivious to fashion. She appeared game for this adventure but I sensed it was not her idea. "She doesn't know if she will be sea-sick," her boyfriend explained to us. "I said she must think of something else if she feels sea-sick."

Our motorized rubber dinghy sped past mountains sharp and black as serrated graphite. Churning up a fast wake, the boat bounced us unmercifully, and I was glad I had a relatively safe seat, next to Jens, who stood and steered with one hand. My knees were braced and my stomach lurched from rubbery floor to the back of my throat; still, it was better than sitting on the buoyant edge of the raft. Sue, blond hair flying, had a tight grip on a plastic rope and a slightly grim expression. It was a good thing we'd discussed Poe before leaving the harbor, for now no conversation was possible. Mostly I was dreading seeing Sue ping-pong off the raft into freezing northern waters.

Poe never visited the Lofoten Islands before he wrote his celebrated story, "A Descent into the Maelstrom." He took his accounts from travelogues and the Encyclopedia Britannica and embroidered them:

A panorama more deplorably desolate no human imagination can conceive. To the right and left, as far as the eye could reach, there lay outstretched, like ramparts of the world, lines of horridly black and beetling cliff, whose character of gloom was but the more forcibly illustrated by the surf which reared high up against it its white and ghastly crest, howling and shrieking for ever.

The dramatic tale of how a man survived the Maelstrom's pull is told to the narrator by its survivor as the two of them sit on a precipice overlookingthe fearsome whirlpool. Before the horrible story even begins, the narrator hears "a loud and gradually increasing sound, like the moaning of a vast herd of buffaloes upon an American prairie." Finally (like me, the narrator can barely stand to look down, much less out to sea, from a high cliff), he locates the source of the uproar between the island of Mosken and the coast:

Here the vast bed of the waters, seamed and scarred into a thousand conflicting channels, burst suddenly into phrensied convulsion—heaving, boiling, hissing—gyrating in gigantic and innumerable vortices. . . .

and as if this weren't bad enough, the convulsions soon subside into a single vortex:

The Italian girl looked pea-green, a pretty combination with her red suit, and clutched her boyfriend in the front of the dinghy. White water splashed up all around us. The coastal mountains, while not the "ramparts of the world," still gave an impression that they separated us from the rest of the civilized universe on our journey to hell. We were jostled relentlessly. Sue fell into the center of the raft, and pushed herself back onto the balloon rim. I thought I heard her say, "Bloody hell." Jens seemed unperturbed; the more the current yanked us through the sea, the more he revved up the speed. I could barely see at times, my eyes were squeezed against the salt. Once I glimpsed my hand, very small at the end of a huge red sleeve. It was white-knuckled, wrinkled with ocean water.

Poe had probably never been to the American Prairie and heard a vast herd of buffalo moaning, but the analogy was surprisingly apt. The water around us churned and rumbled in its flow, like the surf mill of the ancient skalds. We were approaching the end of the large island of Moskenes, and in front of us was a heavy green sea with a few remote islands sticking up like fingertips. When we went around the corner of Moskenes, we'd be in the Norwegian Sea, a more northerly body of water than even the North Atlantic. It was where the Norwegian Sea and the Vestfjord slapped together that the tidal pull was strongest. The strait through which we'd be passing was about four or five kilometers across and considerably shallower than the ocean bed on either side. The tide came into the Vestfjord twice a day and the difference between high and low tides can be up to four meters. Midway between high and low tides, the current changed direction. It was this that caused the waters to rush and funnel into whirlpools, sometimes with speeds of up to six knots. Sometimes the separate eddies or vortices joined together to make a larger whirlpool, whose power came from below and could create a funnel effect.

In Poe's imagination, a vortex was addictively inescapable, but also sublime with unexpected beauty:

The boat appeared to be hanging, as if by magic, midway down, upon the interior surface of a funnel vast in circumference, prodigious in depth, and whose perfectly smooth sides might have been mistaken for ebony, but for the bewildering rapidity with which they spun around, but for the gleaming and ghastly radiance they shot forth, as the rays of the full moon, from the circular rift amid the clouds which I have already described, streamed in a flood of golden glory along the black walls, and far away down into the inmost recesses of the abyss.

A motorized dinghy is not a dismasted fishing smack, however. Jens had cranked the motor up to high, the idea being, I supposed, that our lightness and speed would carry us over any vortices attempting to suck us into any abysses. The strait was narrow here; I couldn't see much except the rocky shore to our right. Everything was frost spray and movement. I imagined leaning over the side of the dinghy to stare into the vortex; I imagined the roaring timelessness of the ebony-sided funnel. In Poe's story, the man in the trapped fishing smack sees a hundred broken objects swirl in concentric circles about him in a Goyaesque nightmare before plunging straight down to the center. But he notices that intact objects, like water barrels, don't break apart; nor are they sucked into the abyss. He lashes himself to a barrel and is saved from the funnel's pull; when the Maelstrom finally dissipates, he's thrown up to the surface and carried toward shore and rescued. Why did we carry no water barrels?

Feeling vertigo, I tried not to think of Poe, but of another Norse tale, The Lay of Hymir, which tells of a visit by Thor to the golden hall of Aegir and Ran, the married gods of the sea. "Brew some ale for the gods," Thor demands. Aegir, angered at the peremptory tone, says coolly, "I've no cauldron that would hold enough. Bring me a cauldron, Thor, and I'll brew ale for all the gods." None of the gods knows where to get such a cauldron, until one-handed Tyr volunteers the information that his father, the giant Hymir, has a huge cauldron five miles deep, a "water-whirler." Tyr and Thor eventually manage to reach Hymir's hall, where they find not one, but nine cauldrons. Hymir smashes eight of them, but Thor and Tyr manage to steal the ninth for Aegir, who then becomes "the ale-brewer." The sea could be Ran's Road, a highway of death, but it could also be a golden palace, a storehouse of plenty, with a cauldron that never stops brewing, a cauldron of regeneration.

The Norse had other explanations for whirlpools. In 1957, Roger Corman, king of the B-flick, directed a bizarre movie that traded on the notion of serpents in the sea causing disturbances. The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent was shot over a period of ten days along some California beach and in Monument Valley. Half the women wear flaxen Brunhild wigs and all are statuesque in short, belted tunics. When the story begins, the women are worried about what has become of their men, who set off some weeks before in a ship and haven't been seen since. Should the Viking women stay and wait or should they go in search of the guys? There's conflict between an evil, dark-haired girl and a blond heroine, but in the end the women pull a long ship down to the shore and get in. Not long after, what looks like a storm comes up, but it's not a storm, it's a whirlpool, caused by a giant sea serpent.

I'd watched this film twice at home. In spite of its awfulness, it had two of my favorite themes: seafaring women and whirlpools. Of course, the northern version of a whirlpool reflects Norse mythology, which has always seemed to me far too fixated on evil and its will to power. The monster doesn't lie at the heart of the labyrinth as in the Greek myth of Theseus; instead, the monster is the labyrinthine vortex, its coils clenched around the world. In this cosmology, the sea serpent, Jormungand, is the second of nasty Loki's even nastier children, hurled by Odin into the ocean surrounding Midgard, where humanity resides. The sea serpent hurtles through the air, crashes into the waves and disappears, not to die but to thrive. He grows so thick and so long that eventually he encircles the whole world and is able to bite his tail. Except for a few brutish appearances, there he stays until Ragnarok, the violent end to the world. In addition to imagining the sea serpent as somewhere down below in the terrifying abyss of the ocean, the Norse also configured a map that showed an inner sea surrounded by land surrounded by an outer sea, and all of it surrounded by a great serpent biting his tail. The voyagers were afraid of sea journeys that might take them from the inner sea to the outer sea and into the clutches of Jormungand.

But there were other explanations for whirlpools or ocean whirls than the sea serpent. The King's Mirror, a late medieval Norse text, describes such a phenomenon:

It is called halfgerdingar [ocean whirl] and it has the appearance as if all the waves and storms of the ocean had been collected into three heaps out of which three great waves form. These so surround the entire sea that no openings can be seen anywhere; they are higher than lofty mountains and resemble steep overhanging cliffs. In only a few cases have men been known to escape who were upon the sea when such a thing occurred.

Far off the coast of Iceland, midway to Cape Farewell on Greenland, was such an ocean whirl. Sailing directions from the nineteenth century mention that the sea broke strongly in that area and it was believed that the cause was volcanic. When Erik the Red and his followers sailed to Greenland in the first colonizing effort, only fourteen of the twenty-five ships made it. The rest were caught up in the ocean whirl and drowned.

I preferred thinking of a whirlpool as the umbilicus maris, the navel of the sea. Even though the vortex led downwards, perhaps to the hollow center of the earth, perhaps to Ran's realm, it was the spiral shape the stirred waters made that intrigued me. So often when you saw the shape of a whirlpool in art, it was as though you were looking at it from above. It always resembled a labyrinth, a circular path leading to a center. It was that inevitable center that fascinated me. In a stone labyrinth you picked your way closer to the heart of things, via paths that often dead-ended. In a whirlpool you were funneled along with the flotsam and jetsam of your life into the core depths. Either way you came to the center, or as close as you were able.

Finally, just as I trembled on the verge either of revelation, or of falling in, I noticed that the motion lessened. We were still bucketing and plummeting, but it was more like riding river rapids. True it was not a river, it was the Norwegian Sea, but we were not being drawn into a giant funnel; we were bouncing over the eddies like a beach ball. I began to breathe more deeply. White clouds tugged at the limits of the cerulean sky; on the small islands to our left were hundreds of cormorants and sea gulls; puffins sped like tiny turbojets above the surface of the water. And when we rounded the headland and passed out of the main pull and swirl of the current, there were inquisitive seal heads to greet us.

"What's all the fuss?" they seemed to ask.

Had I seen the abyss and missed it? Had we avoided the angry tail of the wrathful sea serpent? Or had I been inside the cauldron of regeneration and come out again?

Adam of Bremen tells the story of the Frisian sailors who fell into the whirlpool and found tubs and vessels of gold inside, which echoes the myth that a circular current is a cauldron of plenty. At the end of Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, Jules Verne has Captain Nemo disappear into the Maelstrom at the climactic end; in the novel's sequel, The Mysterious Island, we learn that Nemo's sub, the Nautilus, escaped and took him far across the seas to the South Pacific, where he found his way to the center of an island with resources sufficient for his needs. The Greeks tell of a mythic isle amidst the currents. It belongs to Calypso, it's the Omphalos Thalassos, the navel of the sea.

Stories of descent are stories of initiation. There are treasures below. They lie at the bottom of the vortex, at the center of the labyrinth. I'd continually been talking of crossing the Maelstrom, of getting across it, through it, and that's what we had managed, in a buoyant raft that skittered like a dragonfly over the swirl and suck of eddy and flow. Yet it was, of course, the depths, unknowable, frightening, that promised riches, gold in the cauldron, an island of plenty below.

"You see," said Jens nonchalantly, taking us ashore on a sandy beach and immediately reaching for his cigarettes and pulling on his smile bands. "Everybody thinks they are going to fall into the water. But nobody does."

We were all so water-sprayed, however, it felt as if we had been inside the sea. We struggled out of our red suits and sat for a few moments on the stones by the shore, speechless. The Italian girl had no color at all in her face; even the green had leached out. Jens had other plans for us. "It's a short walk," he promised. "Maybe half an hour, a little more, to the caves."

Oh yes, the famous cave of Refsvika, with its prehistoric drawings that had only been discovered in the mid-eighties by a class of archeology students. Without flashlights, the people of Refsvika had never noticed the figures on the cave walls, even though they'd sheltered and milked their goats inside for centuries. The last of the Refsvikans had left this promontory decades ago; not a single structure remained. "The women used to walk this trail four times a day to milk their goats," Jens said, goading us on over the next hour over a muddy and often disappearing path up and down the sides of a steep mountain. "They carried the milk in two buckets while they walked." On the way to the cave I managed to keep up, but returning to the dinghy, muddy in the knees from a fall or two in a boggy stretch, I hung back and talked with Sue. The cave paintings, 3,000 years old, were eerie and wonderful, we agreed, red figures dancing in the darkest parts of the cave; still, it was the Maelstrom that drew us.

"I don't suppose you'd like to exchange places on the return?" she asked slyly.

"I admire people with physical courage more than anything else in the world," I said, "because I have so little of it myself. May I just continue to admire your bravery from my seat next to Jens?"

"Just as long as you let my children know how I went." We had suddenly become good friends, the way you can on an adventure.

Jens had urged us on with laconic threats about missing the tide, but once we were suited up again and back in the dinghy he seemed in no hurry to round the point again. He cruised for a bit out into the Norwegian Sea, as if it might be nice to cross over to Greenland over the top of Iceland, and told us about the seals and how they waited for the eddies to stir the fish up to the surface. He said, "The Moskstraum is very good for the seals and the fishermen. If you have the guts to look in the current, you will find lots of fish."

Then, still leisurely, he turned the raft in the direction of the Maelstrom and took us through again. This time, it seemed bumpy but far less chaotic. Was it a difference in the tide or in the way Jens was handling the dinghy? I wondered for a moment, as I'd found myself wondering on a raft trip down the McKenzie River in Oregon, whether we'd been intentionally steered through white water just to make sure we had a few thrills.

If so, we'd gotten our money's worth.

We dropped the two Italians off at Moskenes so they could catch the ferry for R¿st. "What makes you want to go there?" I managed to ask as they got ready to spring on to shore. "Pietro Querini," said the medical student. "He was shipwrecked there." His girlfriend popped out of her red suit, remarkably crisp looking, but no more enthusiastic than before.

I got back to my rorbu around seven, done in by the unexpected steep mountain hike more than the raft trip. I peeled off my muddy trousers and took a long hot shower. In spite of some aches, I felt wonderful. The night before in Å I'd tried to cheer myself up by eating dinner at a restaurant. The bill at the end itemized my ineffective attempt at mood alteration through fine dining:

1 Reindeer

1 Glass Wine

1 Cheesecake

That night I had a cup of soup, some Finn Crisp, cheese and an apple. Every bite tasted delicious as I sat at the kitchen table with its view of the ochre and red houses built on wharves over the harbor, and the green-frosted black mountains behind. Our English vocabulary for heightened enjoyment—gusto, relish, appetite—all have to do with eating. Even zest, meaning the fine sharp peel of a lemon or an orange, has come to signify the vigorous appreciation of life. Odd to think about lemons then, but zest was precisely what I felt, sitting with wet hair and pleasantly aching muscles, and eating my cheese and crackers in front of the kitchen window. It's physical aliveness that makes food taste good. It's doing something really frightening, and coming out of it alive.

I had gotten into a rubber dinghy in the Norwegian Sea. I had looked into the eye of a watery labyrinth. I had crossed the Maelstrom, and I hadn't drowned.