Singin' in the Rain: A Conversation with Betty Comden and Adolph Green

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Baer: In 1946, after the great success of your Broadway musical, On the Town—with its score by your friend Leonard Bernstein, you were offered a Hollywood contract to write musicals for the Arthur Freed unit at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. What was Arthur Freed like?

Comden: He was actually a very complicated man. Before becoming a producer, he was a songwriter and a great lyricist. He was also a man who was used to working with highly talented people, and that's what made the Freed unit so unusual. More than anybody else in Hollywood, Arthur brought people out from New York who were not necessarily movie people and put them to work. Peopl e like Alan Jay Lerner; Vincente Minnelli; Oliver Smith, the designer; and anyone else he thought was exceptionally talented. That was one of his greatest gifts: the ability to bring people together and get them to work together.

Green: Arthur had a real instinct" about things, and he also had a most invaluable assistant in Roger Edens, his second-in-command. Roger was extremely important at M-G-M; he was just like Arthur's co-producer —his partner, really—and he was involved in every aspect of the Freed productions.

Comden: The writing, the music, everything. And Roger was a very talented musician himself.

Baer: So you dealt more with Edens?

Comden: Yes, right from the very beginning.

Green: We only dealt with Arthur on and off. He was very friendly and nice and helpful, and he was never a tyrant or anything like that, but he was always so busy. So Roger was the one we worked with every day.

Comden: As members of the Freed unit, we had a very unusual experience for writers in Hollywood. The unit had a reputat ion for being very respectful of all its various talents, particularly the writers, and it was true. No other writer was ever put on one of our pictures, and no one was ever brought in to rewrite anything. Never. Which was very unusual.

Green: And very pleasant. Although our office in the Administration Building was barely better than a prison cell! It was bleak and stark, and our window looked out on the Smith and Salisbury Mortuary. That was our daily view.

Comden: Arthur was right down the hall in the corner office . . . in his suite of offices.

Green: So we'd come in early every day, and we'd work like mad in that little room.

Comden: When we first arrived in 1946, we were stunned to learn that our first assignment was Good News, a rather hokey campus football story from 1925! We were considered—I hate to use the word, but it was our reputation back then— rather sophisticated New Yorkers, and then we were handed Good News!

Green: We'd done On the Town and our second Broadway show, Billion Dollar Baby, and our reputation was for sharp satire and sophisticated dialogue, and then we got Good News which was pretty much old-hat" when it was first produced on the stage. But it was a tremendous hit in New York, and it had a wonderful score.

Comden: So we were trying to come up with new and clever ways to rewrite it, and Arthur said, No, kids, just write Good News." So we did our best to keep to the original story line.

Baer: Then you wrote The Barkleys of Broadway for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, and then you adapted your own On the Town, both of which came out in 1949. I'm jumping ahead a bit to get to Singin ' in the Rain.

Green: Absolutely. Skip all that!" as the Bellman said to the Baker in The Hunting of the Snark" when the Baker started his sad story: My father and mother were honest, though poor—."So the Baker did as requested, 'I skip forty years,' said the Baker in tears."

Baer: Well, let's not skip that many years. But let's jump ahead to the summer of 1950, after the success of the film version of On the Town , which starred Gene Kelly and Frank Sinatra. Arthur Freed called you back to Hollywood for what was known as a catalogue" picture—a picture that's created around the songs of one songwriter or team of songwriters.

Comden: Yes, we walked into Arthur's office, and he said, Well, your next movie is . . ."

Green: Kids!"

Comden: That's right, kids,"—he always called us kids"—Well, kids, your next movie is going to be called Singin' in the Rain, and it is going to have all my songs in it. " And that was that. That was the whole assignment. And it may not sound very difficult, but it was terribly hard to do, almost impossible.

Baer: Is that because you have to make all these unrelated songs somehow fit into the story you're creating?

Comden: That's right, you have to create a whole new story with characters and situations that fit the already existing songs. It's like working backwards.

Baer: And, of course, you're obligated to include the most popular songs.

Comden: Yes, but the very first thing you have to do is come up with an overall idea for the movie that'll be appropriate to the general feeling of the songs. And that was very hard to do, but we finally figured it out.

Green: Finally! It took us quite a long time before we realized that the songs would fit best in the time period for which they'd been written. Most of them, at least.

Comden: Which was the changeover period in Hollywood from the silents to the talkies, when Arthur Freed and his partner, Nacio Herb Brown, wrote many of their songs for the early film musicals.

Green: Broadway Melody," for example—which was a very big hit when it came out in February of 1929.

Comden: And Singin' in the Rain."

Green: Singin' in the Rain" was first used in The Hollywood Revue of 1929 directed by Charles Riesner.

Baer: How many Freed-Brown songs were there?

Comden: About a hundred or so. He gave us a huge stack of songs and said, Go write a movie."

Green: But a movie about what? That was the problem. All we knew was, that at some point in the film, someone would be out in the rain and singing about it.

Baer: I've read that you were never crazy about the title. And both Kelly and Donen have also claimed that they never liked it.

Comden: It really didn't bother us. We liked the song; we liked lots of the Brown-Freed songs.

Green: The problem wasn't the title; it was that we had no picture to go with it!

Baer: When you arrived in May 1950 to write Singin' in the Rain, you didn't realize that you'd be writing a catalogue picture. You assumed that you'd be writing both the story and the lyrics for your next film.

Comden: We did. It was our own mistake because our previous agent had told us that it was in our contract that we'd always write our own lyrics, unless they were usin g songs by Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, and a few others.

Green: So we went on strike! We didn't work for about six weeks.

Comden: We stood firm, saying, Look at our contract!" Then Irving Lazar, our new agent, came over one day and read the whole contract, and there was no such clause. So we were wrong.

Baer: It's a good thing. We might not have Singin' in the Rain.

Comden: That's true.

Green: So, Arthur said, O.K., kids, let's get to work." And we knew we had no choice, so we got to work.

Baer: The key to Singin' in the Rain, as we've already discussed, was setting the film in the late Twenties when the silent" films gradually gave way to talking"pictures. Back in your earlier days as performers in New York, you apparently did a satirical sketch in your show The Revuers" about the Hollywood transition period—and especially about the resultant problems with synchronization. What was the sketch about?

Comden: Well, first I should mention that Adolph is quite an expert on the movies. He knows everything about the history of film.

Green: And Betty knows a great deal too.

Comden: So even back when we were performing our nightclub act with Judy Holliday, which consisted of a variety of sketches and satirical songs, we had this one about the first time sound and image met on film—nearly!

Green: It was a sketch about a movie actor cal led Donald Ronald. And we first showed him in a silent film, and then we showed him in an early talkie. Sort of like Al Jolson. And I walked on and I said . . . [mouthing the words out of sync].

Comden: [Saying the words for Adolph] Hello, old man. Won't you come in? What's that you say? She's dead! No, no, no! I'll go for the doctor. Oh, Nellie, Nellie, my own!"

Green: So we used that directly in the movie.

Comden: The other bit, of course, was that some of the actors forgot to keep close to the hidden microphones, so the sound kept modulating up and down, and you could only hear part of a song.

Green: I sang a song called Honeybunch." The lyrics went: Honeybunch, you drive me frantic with your smile. Honeybunch, you're worthwhile." [Singing the lyrics with the sound drop outs] Honeybun . . . frantic with . . . while." So we used that in the movie too.

Baer: Apparently, the technicians working with the footage from Singin' in the Rain were so confused by the non-synchronization" scene that the answer print was actually delayed for a few weeks.

Comden: Yes, they kept trying to make it match, and Gene and Stanley kept calling them up saying, Where's the print? What's holding things up?"And they were very embarrassed, but they finally admitted, We can't get this thing in sync." So Gene and Stanley had to explain to them that that was the point. It shouldn't be in sync!

Baer: Given that you're both great lovers of the silent pictures that you saw when you were younger, I wonder if either of you actually ever saw John Gilbert's His Glorious Night (1929) which supposedly ruined his career? Especially when he repeated, I love you, I love you, I love you . . ."

Green: I saw it.

Baer: In a movie theater when it first came out?

Green: Yes.

Baer: What was the audience reaction? Was it really as shocking as we've been told?

Green: Well, it was quite a shock, and it ended his career, pretty much overnight. It was very sad. As a kid, I was crazy about John Gilbert, but when I heard him speak for the first time in His Glorious Night , it definitely didn't sound like him—or, at least, like what I expected him to sound like. And when he kept saying I love you, I love you, I love you," the audience laughed out loud. It's true.

Comden: A lot of the silent stars had voices that didn't seem to fit their screen personalities.

Green: And, in some cases, the sound hadn't been properly adjusted to equalize their voices and make them sound okay.

Baer: Apparently, they delayed making a talkie with Garbo because they were afraid her accent wouldn't work? But the audiences loved it.

Green: Yes, in Garbo's case, her voice—accent and all—sounded exactly like what she looked like. It was a perfect match. But poor John Gilbert had no such luck. He was the biggest star in films back then, and the studio had to pay him enormous sums of money over the next seven years while his career just frittered away. It's a very sad story, but our picture was funny!

Baer: It's especially funny when Gene Kelly insists on saying the line.

Green: I love you, I love you, I love you."

Comden: Yes, and he thinks it's a great idea!

Green: Yes, we liked that picture a lot. We've gradually gotten to like it.

Baer: Singin' in the Rain?

Comden: He's just kidding! You can't always tell with him.

Green: Yes, I'm sorry. As a matter of fact, we loved it from the very beginning, but we had no idea it would reach such epic proportions as it grew older. Initially, it was pretty much brushed off since it came out right after . . .

Comden: An American in Paris.

Green: . . . which got so much publicity and so many favorable notices.

Comden: And was considered Art."

Green: So our picture didn't seem as important. Mainly because it was full of laughter—that sinful, superficial thing called laughter.

Comden: But we knew it was good from the start. Even before Gene decided to do the picture, we read the script to a number of people, and the response was always terrific.

Baer: In that excellent introduction you wrote for the published screenplay of Singin' in the Rain in 1972, you mentioned that, at one point, you were considering a singing cowboy"plot revolving around Howard Keel before you knew that Gene Kelly would be the lead.

Comden: Yes, briefly. We were searching around for ideas at the time, and since we didn't have Gene yet, we had to consider other actors who might be available.

Baer: How did your good friend Gene Kelly get involved?

Green: Well, at first, he couldn't even consider the idea because he was in the middle of shooting An American in Paris.

Comden: We used to go down to the set where he was shooting, but we had to wait until he was finished with the picture. Finally, we did an audition"for him, and we read him the script. At that time, Gene had his choice of anything that he wanted to do, but he fell in love with Singin' in the Rain right away.

Baer: I believe you first met Gene Kelly in the summer of 1939 at the Westport Country Playhouse?

Comden: Yes, the Westport Country Playhouse was wonderful summer theater; it was a revue, and we were in it.

Green: Meaning our nightclub act, The Revuers," with Judy Holliday, Alvin Hammer, and Joan Frank.

Comden: And there were a number of other people on the bill including Gene.

Baer: Was he working as a choreographer? Or a master of ceremonies?

Comden: No, he was dancing.

Green: He had a dancing act. It's true that he was trying to get some work as a choreographer, which he did later, but, at the time, he was just a hoofer—and he had a very good act.

Comden: He was such an attractive guy—adorable, wonderful-looking—and very funny.

Baer: Going back to when you first began to write the script, you were apparently struggling with three possible openings for the film. What were they?

Comden: Well, one was the premiere of the new silent film in New York City; the second was a magazine interview where he's telling lies about his past; and the third was a sequence from the silent movie that was being premiered, The Royal Rascal.

Green: But they all felt too much like openings." None of them made it seem like the plot was really starting. So we had these three unsatisfactory ideas, and we knew we'd have to use one of them, and we were in total despair. We were ready to give the money back.

Baer: Was it really that bad?

Green: It was. We were always in despair at the beginning of all our projects, but Singin' in the Rain was just impossible. We were ready to give up and go back to New York.

Comden: We thought we'd never solve it.

Baer: Then your husband came out for a visit.

Comden: That's right, my husband, Steve, came out to be with me, and we read him all three openings, and he said, Why not use all the openings?"And we realized that he was right, and we worked it all out, and it solved the problem.

Green: All three ideas ended up in there—intertwined—and it worked. And Gene sure looked great in that white hat and the white coat at the premiere.

Comden: Yes, didn't he look terrific?

Baer: After he decided to do the picture, you began meeting with Kelly and his co-director Stanley Donen to discuss structure and go over the film shot-by-shot.

Comden: Yes, we worked at the studio during the day, but, in the evenings, we'd often go over to Gene's house. Then we'd talk about the movie and discuss what we needed to do.

Baer: Did you act out the scenes?

Green: By that time, it wasn't necessary. Gene and Stanley knew the script well enough. So we'd read parts out loud or turn to certain pages and say, Hey, I think we need to do this here."It was mostly patching things up, discussing costumes, sometimes deciding to rewrite two scenes into one—those kinds of things.

Comden: We had a great shorthand with both Gene and Stanley because we were all old friends, going back to our nightclub days. So we didn't have to explain things to t hem. Another director might have said, What is this craziness? What do you think you're doing?" Or How the hell are we going to do that?" But Gene and Stanley were used to the way our minds worked.

Green: Other directors might have panicked and thrown out the whole script. So we were very lucky. Gene and Stanley were always able to visualize the script. And as much as a film can ever resemble its script, Singin ' in the Rain was extremely close to the screenplay. Wouldn't you say so, Betty?

Comden: It certainly was. Fortunately for us, Gene and Stanley were both so visually creative, and they had that masterful sense of pace. In so many movies, things are leaden and heavy . . .

Green: Belabored.

Comden: . . . usually because the director spends too much time on things. But in Singin' in the Rain, there isn't a wasted second. The important points are made in every scene and then it moves right along to the next scene. It's brilliantly done.

Baer: There's no doubt about that. Now, I'd like to ask you a couple o f questions about the casting of the picture. Debbie Reynolds was a very talented seventeen year old with limited film experience and only one year of dance training when she was unexpectedly given the lead in Singin' in the Rain . Her Aba Dabba Honeymoon" number with Carleton Carpenter from Two Weeks with Love (1950) had brought her some attention, but I wonder if you were concerned about the studio's choice?Comden: We weren't worried. We'd seen Debbie perform one evening. She got up and sang and danced, and she was very cute and talented. She wasn't really a dancer, but she worked very hard at it, and it paid off.

Green: Everyone considered Debbie up and coming" at the time. She was very cute and funny, and we were both convinced when she performed for us that night.

Comden: It turned out to be a great call. So was the casting of Jean Hagen. She was wonderful too.

Baer: How about Donald O'Connor? He was borrowed from another studio for the role of Cosmo, but I've read that Arthur Freed really wanted Oscar Levant for Kelly's sidekick?

Green: Well, we actually started writing the script with Oscar in mind.

Comden: Oscar had been the sidekick in American in Paris, and it was more or less assumed that he'd do the same thing in Singin' in the Rain.

Green: It was very difficult for us because Oscar happened to be a very close personal friend.

Baer: Was it Kelly's decision?

Comden: Yes, Gene went to Arthur and said. I don't want to work with Oscar again. This is a different kind of movie, and I need somebody who's more of an entertainer—somebody I can dance with."

Green: He didn't want any more of those scenes with Oscar sitting at the piano and Gene dancing on top of the piano. We felt terrible about it, but we knew that Gene was right, even though we loved Oscar.

Comden: So we went to Arthur and warned him, Oscar's going to be very upset about this." But Arthur reassured us, Don't worry, kids. Oscar's a good friend. I'll tell him myself."So we assumed that Oscar knew. Then one day, I was talking to Oscar on the phone and I said, We just feel terrible about the movie, Oscar," and he said, What? What?" And that's how he found out about it. Arthur never told him.

Green: Arthur was like that sometimes. He didn't want to give the bad news, even though he'd told us it was no problem. So Oscar was furious at Betty.

Comden: It lasted about four months.

Baer: Why was he mad at you?

Comden: I was the messenger!

Green: He didn't blame me because I wasn't the one on the phone.

Comden: So I was the guilty" one. It was terrible, but, gradually, we made up. And, of course, Gene was absolutely right. He needed someone to dance with, and Donald was his first choice.

Green: Early on, Gene brought Donald to the studio to see what he could do, and he had him do every single dance step that Donald knew—and every joke, and every pratfall. Later, of course, they were all used brilliantly in that crazy number, Make 'Em Laugh."

Baer: Back when you were writing the role of Lina Lamont, were you thinking of Judy Holiday's Billie Dawn character in Born Yesterday?

Comden: Not really. We felt that a character like that—with that kind of voice and with that kind of a nasty personality —had nothing to do with Judy.

Green: But we did wonder if it might raise some questions. Which it did. Although, oddly enough, never from Judy herself.

Comden: Well, we tried very hard to avoid any possible resemblance. We made her a total heavy, not a little girl who was finding herself, like Billie Dawn.

Baer: Singin' in the Rain is full of film references—to Clara Bow, Busby Berkeley, John Gilbert, George Raft, Louise Brooks, etc.—and a number of people believe that the character of R. F. Simpson was modeled on Arthur Freed himself. Is there any truth to that?

Comden: I've never heard that before. It certainly wasn't intentional, and he sure didn't look like him!

Baer: People claim, for example, that Arthur Freed was known to be clumsy, and that he would often have difficulty making up his mind about things.

Comden: Well, it's certainly true that Arthur could have trouble making up his mind sometimes. It's also true that he occasionally took credit for certain things that he shouldn't have. Like in the movie, when Simpson claims that he warned everybody about the coming threat of the talkies.

Green: Yes, Arthur could have done that, but, I suppose, many other producers could have done it as well.

Baer: Is it true that the studio was worried about your satire of the powerful gossip columnist Louella Parsons?

Comden: I've never heard that either. Arthur never told us to go easy" on that character, or anything like that. Did he, Adolph?

Green: No, but I guess she is a bit Louella-ish.

Baer: I've heard that she enjoyed it very much.

Green: She probably did. Dora Bailey wasn't a mean character in the film, and she wasn't even that dopey.

Comden: In real life, Louella Parsons could seem quite formidable and scary. And she had the ability to damage people's careers if she didn't like them. But we didn't create a character like that. Dora's a bit silly and gushing, but she's very likeable.

Baer: One important change from the earlier script to the film is the replacement of the Wedding of the Painted Doll" number for Make 'Em Laugh," which Arthur Freed wrote the night before rehearsal s. Apparently, since he was held in such affection by the people who worked for him, no one pointed out—in public, at least—the song's marked similarity with Cole Porter's song Be a Clown,"which, ironically, was first sung by Gene Kelly and Judy Garland in The Pirate (1948), which Arthur Freed produced. What was your reaction to all this?

Comden: We just looked at each other, raised our eyebrows, and moved on.

Green: We shrugged our shoulders and said nothing. Everybody did.

Comden: Should I tell the story about Irving?

Green: Sure. Why not?

Comden: On the very day that they were shooting the song, Arthur brought Irving Berlin down to the studio. He was very proud of both the song and the number. So Gene was in the process of shooting the number, and Irvin g walks onto the set, and we were all horrified. We were all thinking, My God, Irving's going to hear the song and recognize the similarity! What's going to happen?"Then they put the song on the track, and it played for a little bit, while Arthur's sitting right there with Irving, feeling very proud of it.

Baer: So, obviously, he had no idea?

Comden: He had no idea. No clue. So Irving's listening, and he's listening, and then you could see his face changing. Then he turned to Arthur and said, Who wrote that song?"And Arthur, who had written it himself, suddenly got very flustered and said, Oh, well, we . . . that is, the kids . . . we all got together and . . . come along, Irving!"Then Arthur pulled Irving away, and they left the set, and we all fell on the floor laughing.

Baer: So he must have realized at that very moment?

Green: He must have.

Comden: But how he could have written it in the first place—and not realized—is still a mystery. We have no idea, and we never brought it up with Arthur, either before or after that day.

Baer: I don't know how Cole Porter took it, but it's a wonderful sequence in the movie—one of the best musical numbers in film history.

Green: It's great.

Comden: It's fabulous, but the song's exactly like Be a Clown."

Baer: The only non-Freed song in the movie was the tongue-twister Moses Supposes" which Roger Edens set to your lyrics. Was the song finished before you left for the east coast?

Comden: I think so. We incorporated it into the film while we were still out there, didn't we?

Green: I think we did.

Baer: As production actually got under way on Singin' in the Rain , you went back to New York to prepare another play for Broadway. While you were gone, Kelly and Donen never altered a line of your script without your cons ent, and they occasionally called you up from Hollywood during the shooting of the film. Can you remember any of these long-distance discussions?

Comden: One was about the tour of the studio lot with Gene and Debbie. Originally, it included three songs. Then we got a call from Gene that he wanted just one—a love song.

Green: Originally, they were taking a tour of various locales on the set—India, China, Germany, etc.—a world to ur in five minutes around the studio. But Gene wanted the chance to sing a love song in a single location, and he was right. So we wrote the scene for the sound stage, and we sent it through the mail.

Baer: When did you finally see the completed film?

Green: It must have been when we went out there to get our next assignment, which was The Band Wagon. Singin' in the Rain hadn't been released yet, and we saw it in some grubby little equipment room—not even a screening room—and we carried in two chairs and sat down and watched it for the first time.

Comden: It was wonderful!

Green: We were thrilled!

Baer: Were you all alone?

Green: All alone.

Comden: All alone. And it just knocked us out!

Baer: Could you tell me about the party you attended with Charles Chaplin soon after the film was released.

Comden: Was it at Charlie's house?

Green: No, it was at the Contes. Nick and Ruth Conte. And Charlie came in.

Comden: Yes, he came into the party, and he said, I've just seen this marvelous picture!"

Green: He didn't know we had anything to do with it, and he started raving about the film and describing it to everyone.

Comden: And we said, Oh, really?" And we listened for a while, and then admitted, That's our movie, Charlie!"

Green: It was so thrilling because we were always such great Chaplin fans.

Baer: Although you weren't actually on the set for most of the filming, you're both very familiar with how Kelly and Donen worked together as collaborative directors. Could you describe it?

Comden: They worked very closely a nd discussed everything. Stanley is a great cameraman, and he knows all about the angles and the set-ups. As a former dancer, he also knew which particular angles would be best suited to which steps and how to shoot them all. But it wasn't simply a matter that Gene did the dancing and Stanley did the camera; they really did everything together, collaboratively—the choreography, working with the other actors, and everything else.

Baer: One thing about Gene Kelly that's obvious from watching the film is his artistic generosity—his willingness to showcase such remarkable, show-stopping dancers as both Donald O'Connor and Cyd Charisse.

Green: That's the way he was. The picture always came first.

Comden: Gene was always smart enough to surround himself with wonderful exciting people. He didn't want to be the only star. He was the one who'd insisted on Donald O'Connor.

Green: Yes, he wanted him like mad! Gene knew that the more great entertainers the film had, the better it could be.

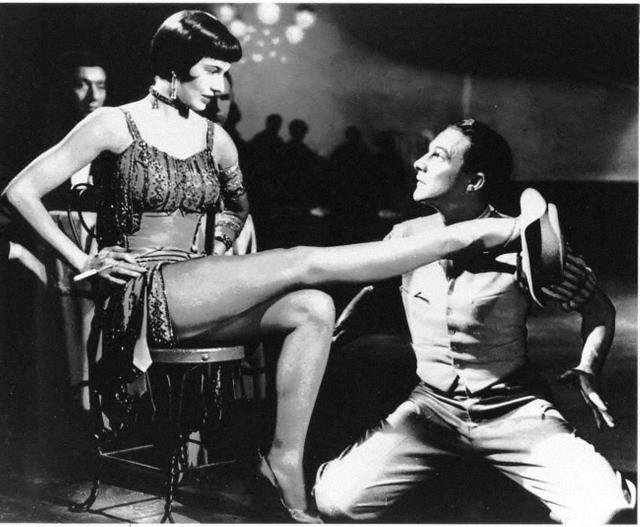

Baer: He not only gives whole dance numbers to other performers, but, in other scenes, he spotlights other characters rather than himself. Like when Cyd Charisse appears in the Broadway Melody"number dressed in that dazzling green outfit.Comden: Well, Gene couldn't wear that! Sorry!

Green: And, as you know, that was the first time that Cyd ever really came across" in a film. She'd been in pictures for a number of years by then, but Gene and Stanley knew exactly how to highlight her talents.

Comden: And that's what Gene wanted. He never felt competitive with his co-stars.

Green: All he cared about was the film.

Baer: I'd like to ask your response to several of the musical numbers in the film starting with Singin' in the Rain," which has become the most famous musical scene in motion picture history. Gene Kelly often said that it was the easiest dance he ever did, and that the real difficulty was the problems faced by the technical crew. But it's also well known that he had a 103° fever that day, that everyone was worried that he might catch pneumonia, and that, between takes, when he was drenched from all that water, he would leave the sound stage to stand in the hot California sun and try to warm himself up.

Comden: Yes, that's all true, and he did the scene rather quickly as well, didn't he?

Baer: Yes, I believe it was two days.

Green: It's an amazing scene! Marvellous!

Baer: The only real criticism that ever pops up about Singin' in the Rain is The Broadway Melody" sequence, which is, as Gene Kelly has always admitted, too long (over twelve minutes)—and which doesn't fit that well into the narrative of such a tightly-structured and fast-paced film. How do you feel about it?

Comden: Well, it was kind of a developing tradition back then. The theater in New York City started having all those second-act ballets after Agnes DeMille's Oklahoma. We had one in On the Town , and most of the shows were using them. Then, when the musicals were made into films, the ballets were included. An American in Paris, of course, had a very daring ballet, so Arthur Freed decided that he wanted a big ballet at the end of Singin' in the Rain—even though it didn't really fit in the film. But we had no control over it.

Green: But it turned out surprisingly well.

Comden: Yes, it did. But, if we'd had anything to say about it back then, we would have made it shorter and more appropriate to the film. It's not really our favorite part of the picture, except for looking at Cyd Charisse.

Baer: Is it true that, since Donald O'Connor had a television commitment to Colgate Comedy Hour, they brought in Cyd Charisse for The Broadway Melody"?

Comden: I don't think we ever knew about that.

Baer: Did you originally include O'Connor in the number?

Green: No, we didn't, but we definitely didn't have Cyd in mind either.

Baer: How do you feel about the scarf dance—which Kelly claims was one of the most difficult things he ever did?

Green: We've grown to love it!

Baer: Which implies you weren't so sure in the beginning?

Comden: Well, at first, I think we were a little taken aback.

Baer: It goes on so long that it heightens your awareness of what they're actually doing with that huge scarf. And then you start wondering how the heck they're actually doing it.

Comden: And why? We don't really care. It's not at all like the rest of the movie.

Green: It's a symbolic umbilical cord of sorts!

Comden: I think she's a bit sexier than that.

Green: Well, yes, but it's umbilical too. It has to be.

Comden: Oh, I don't think so. Our first disagreement!

Green: Yes! Or maybe not, now that I think of it!

Comden: But we love every foot of that film!

Green: Every foot! Even that tired New York number!

Baer: One of the two musical numbers that was cut from the film was Kelly's All I Do is Dream of You,"which he sang and danced in his bedroom on the night he first met Kathy Seldon. It was cut from the film because it slowed down the narrative, but Kelly has always said that it was one of the best dances he ever did in his whol e career. I wonder if you ever saw it?

Green: Yes, I'd forgotten about that number, but we did see it once, and it was wonderful. But it would have slowed down the picture—just like Debbie singing You Are My Lucky Star"—so they both had to go.

Comden: And Lucky Star" was a very nice scene too. Very charming.

Baer: Given the decline of the great studios, I wonder what you think about the future of Hollywood musicals?

Comden: There really haven't been any first-rate musical films since Cabaret, and that was over twenty-five years ago. It's very hard to make them now because the days of the big studios with all their various departments—performers, writers, arrangers, choreographers, costumers, and so on—are gone. Back then a producer could pick whatever he nee ded for a musical right off the lot.

Green: In those days, if they decided on a number they wanted, the set could be up the very next day and they could be shooting the scene.

Comden: But it's a different world now; it's much more difficult.

Baer: How do you feel about the training of younger people today? Can they dance as well, for example?

Comden: I think young people today are very well-trained, especially in the regional and local theaters and in the colleges.

Green: I have the feeling that there are even more people prepared for musical theater now than there were back then.

Comden: They're getting serious training in the colleges.

Green: It's not just, Wow, I'd like to be in a play."

Comden: But nowadays, since everything costs so damn much, it would be very hard to finance a musical film.

Baer: It's a tragedy. If American film ever stood for anything, especially abroad, it was the musical and the western. And both have fallen into disrepair.

Green: They have. And, as for the musicals, even television, which used to have all kinds of Saturday night revues—with top entertainers and dancers—does nothing anymore.

Comden: Which is a terrible shame given all the talented young people out there. Last night, Adolph went to a show called Swing, and he said the cast was full of kids who could really sing and dance.

Green: The dancing was terrific.

Comden: But, of course, being a star is very different. There can only be one Astaire in a generation, maybe in every several generations. And one Gene Kelly. They don't come along very often, but maybe there'll be more in the future.

Baer: But if it weren't for the Hollywood musicals, no one would have known who Fred Astaire was.

Green: That's true. There's no place to showcase such an extraordinary talent.

Baer: François Truffaut once claimed that he'd memorized every single shot of Singin' in the Rain—and that it had inspired him to make his own film about film-making, La Nuit Américaine (Day for Night, 1973).

Comden: Yes, we learned about that in Paris one tim e, at a party given by Gloria and James Jones. When we arrived, we were absolutely delighted to learn that Truffaut was also there. Then, suddenly, he rushed across the room rather breathlessly talking about Chantons sous la pluie . Through his interpreter we learned that Singin' in the Rain was his favorite film and that he knew every shot in the film. We were flattered to death.

Green: And he told us that Alain Resnais felt the same way. So we were feeling very good at that party!

Baer: Singin' in the Rain was one of over forty musicals that Arthur Freed produced for M-G-M and one of countless Hollywood musicals, yet it has been rated by the American Film Institute as one of the top ten American Films, and rated by both Sight and Sound and Entertainment Weekly as one of the top ten films of all time. Why do you think it's so special?

Comden: Because it's perfect! Perfect! Oh, no, just kidding . . .

Green: But it is perfect!

Comden: O.K., but trying to be a bit more objective, I think its uniqueness is the comedy.

Green: It's really funny!

Comden: And there aren't many like that. Most musicals aren't very funny at all. So that's part of it. Then there's the extraordinary talents of G ene Kelly and both directors and everyone else involved with the picture. Every department at the studio was in top form for Singin' in the Rain. Everything pulled together perfectly.

Baer: And what about that script? It's a very clever story.

Comden: That's true! We have to admit, we think it's a marvelous script!

Green: We're very proud of it.

Baer: You've even grown to love the scarf dance!

Green: Yes, we have!

Comden: Even the scarf dance!